Rose sensed she was being watched. Strange men lingered on Sixteenth Street outside her home, derby hats slouched low, taking note of everyone who came and went. They trailed her across the grounds of the unfinished Washington Monument, wading through the herds of grazing cattle and passing by the slaughterhouse situated at its base, where offal was rotting three feet deep; the stench was so bad that Lincoln had taken to spending long stretches of time at a retreat several miles north of the city. They stood paces away as she watched McClellan drill his soldiers on Capitol Hill, jotting notes in her brown leather diary and scribbling in the margins of Yankee newspapers. Sometimes she reversed course and became the pursuer, chasing shadows around corners, finding the whole situation amusing. She suspected she was the victim of private enterprise—an overzealous Northerner who knew of her work, perhaps, or a misguided secessionist offering protection. She recalled a letter from one reputed lover, US senator Henry Wilson, in which he warned that his every movement and act was being observed with “hawkeyed vigilance,” and she wondered exactly how much the strange men had seen.

Undeterred, she summoned her accomplices for a meeting, recounting the teenage courier Bettie Duvall’s mission and toasting the victory at Manassas. “The Southern women of Washington are the cause of the defeat of the grand army,” she boasted. “They have told Beauregard when to strike!” During a feast of terrapin, oysters, and wild turkey, she regaled them with stories about “Ape” Lincoln and his vulgar wife. At his first White House reception, a servant asked Lincoln which wine he’d prefer. He regarded the servant with the most “touching simplicity” and said, “I don’t know: which would you?” Mary Lincoln, at the same ceremony, wore artificial flowers in her hair and was mistaken for a servant.

Rose once ran into Mrs. Lincoln while shopping at the market, spotting “a short, broad, flat figure, with a broad flat face, with sallow mottled complexion, light gray eyes with scant eyelashes, and exceedingly thin pinched lips.” The First Lady was bargaining for black cotton lace, much to the disgust of the shopkeeper, and her dress was inappropriate for a casual outing: the gown of rich silk emblazoned with gaudy flowers; the white hat adorned with feathers, flowers, and tinsel balls; the white gloves and white parasol lined with pink. “I don’t think,” Rose concluded, “that Mrs. Davis would have selected it for that hour and occasion.”

After dinner the women parted red gauze curtains and settled in Rose’s parlor, where they sipped glasses of port and brandished needles and balls of yarn. Little Rose was permitted to say hello to her mother’s guests, curtsying and trilling a few stanzas of her favorite song, “Old Abe’s Lament”:

Jeff Davis is coming, Oh! dear, Oh! dear,

Jeff Davis is coming, Oh! dear;

I dare not stir out for I feel very queer,

Jeff Davis is coming, Oh! dear.

I fain would go home without shedding a tear

About Davis in taking the president’s chair;

But I dare not attempt it, Oh! dear, Oh! dear,

I’m afraid he will hang me, Oh! dear.

Mary Chesnut, the wife of South Carolina senator James Chesnut Jr. and a close friend of the Davis family, witnessed one of Rose’s gatherings: “It gives a quaint look, the twinkling of needles, and the everlasting sock dangling. A Jury of Matrons, so to speak, sat at Mrs. Greenhow’s. They say Mrs. Greenhow furnished Beauregard with the latest information of the Federal movements, and so made the Manassas victory a possibility. She sent us the enemy’s plans. Everything she said proved true, numbers, route, and all.” Chesnut also added a pointed assessment of Rose’s methods: “She has all her life been for sale.”

Sitting at her rosewood piano, Rose surveyed her group. The network was running smoothly despite the unsettling presence of the strange men. The Confederate government had come up with $40,000, likely in donations from private citizens, to assist rebel inmates in the Old Capitol Prison, a fund for buying clothing and writing supplies and bribing guards. Her team of operatives constantly worked the streets of Washington, checking on reports of new fortifications and trailing persons of interest.

As the women tittered and darned socks for the soldiers, Rose outlined their next steps. She’d scored an intelligence coup, meeting secretly with the Union officer charged with alerting Washington in the event of a Confederate invasion. The signal, he confided, was three gunshots from the provost marshal’s office followed by the tolling of church bells. The city’s secessionists needed to be equally prepared. They must cut all telegraph wires connecting military posts with the War Department and spike the guns of Fort Corcoran and Fort Ellsworth; aided by information from her scouts, she had sent detailed drawings of both to General Beauregard. Ideally, they would also take General McClellan and other top officials prisoner, “thereby creating still greater confusion in the first moments of panic.”

After the meeting she sent an update to Beauregard, warning that McClellan “expects to surprise you, but now he is preparing against one,” and dashed off a note to Senator Wilson, scolding him for missing a scheduled rendezvous. “Tonight,” he responded, “unless Providence has put its foot against me I will be with you, & at as early an hour as I can. That I love you God to whom I appeal, knows.”

She filed this letter with others from “H,” tying the bundle with a bright yellow ribbon and leaving it where it could be easily found.

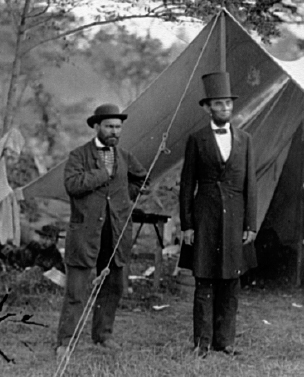

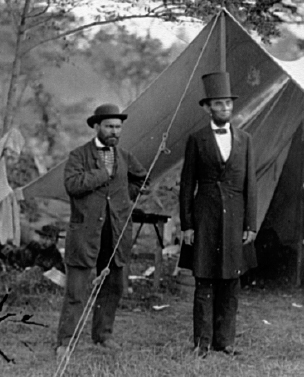

Rose’s surveillance of McClellan had so far failed to uncover one of his most significant acts: the hiring of detective Allan Pinkerton, who had achieved national renown for investigating a series of sensational train robberies. Pinkerton had already served the new administration well, managing security as Lincoln traveled to his inauguration, foiling an alleged assassination conspiracy along the way. He then contacted the president directly, offering to obtain “information on the movements of the traitors, or safely conveying your letters or dispatches.” Pinkerton, whose capacity for self-aggrandizement rivaled McClellan’s own, called himself “Chief of the United States Secret Service” even though his unit was technically nameless.

Working as a civilian under contract to the army, Pinkerton assembled a staff of agents, male and female, who would observe Confederate military preparations and rout out rebel spies. “In operating with my detective force,” Pinkerton wrote to McClellan, “I shall endeavor to test all suspected persons in various ways. . . . Some shall have the entrée to the gilded salon of the suspected aristocratic traitors, and be their honored guests, while others will act in the capacity of valets, or domestics of various kinds.” Pinkerton himself planned to go undercover, using the nom de guerre “Major E. J. Allen,” since his true name was so famous it had, he said, “grown to be a sort of synonym for ‘detective.’” One of his first assignments was to conduct surveillance on Washington matron and suspected spy Rose Greenhow.

Detective Allan Pinkerton with Lincoln.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

One evening Pinkerton dispatched a detective to the home of Horatio Nelson Taft, an examiner for the US Patent Office. Taft’s teenage daughter Julia found a “bland gentleman with distinguished black whiskers” standing in their parlor. He asked if she knew Rose Greenhow, and Julia replied that she did. In fact, Mrs. Greenhow often visited with her daughter, Little Rose, and the family liked them both. Julia had two younger brothers, Bud and Holly, who were playmates of both Little Rose and President Lincoln’s sons, Willie and Tad.

The man nodded, confirming something in his mind. He consulted a list of questions: Did Mrs. Greenhow seem glad to meet the officers who came by? Did she ask Julia, Bud, and Holly for details about their excursions to the White House? Yes and yes, Julia said. Horatio Taft joined the discussion, recalling that Rose demanded details about each new Union regiment that arrived in the city.

“What’s wrong with Mrs. Greenhow?” Julia asked.

She watched the detective pull her father aside. The men spoke in whispers. “Very well,” her father said, and cautioned Julia and her brothers never to mention the detective’s visit, to Mrs. Greenhow or anyone else.

The strange men had entrenched themselves in every aspect of her life. They watched her drift from cart to cart at the Center Market, her maid in tow, sifting through fruits and vegetables, shad and beef, swatting away buzzing clouds of flies. They waited outside Mrs. Arth’s Millinery Shop while she tried on hats, staring back at them from beneath the brims. They stood behind her in line at the sweet-cake and ginger pop stands on Capitol Hill. They sipped whiskey in the lobby at Willard’s Hotel, peering at her through the crowd of office seekers, wire-pullers, investors, artists, poets, generals, statesmen, orators, clerks, and diplomats, noting every ear she whispered into, every man she beckoned with her gloved hand. They followed her into Senate hearings and sat nearby in the gallery, eavesdropping on her conversation. During one such outing Rose turned to a friend and made a disparaging remark about the Federal army, prompting a young Union lieutenant colonel to confront her.

“That is treason,” he warned. “We will show you that it must be put a stop to. We have a government to maintain.”

Rose leaned forward. She looked him up and down, taking her time, tracking from the brim of his kepi to his folded arms to the scuffed tips of his boots. She spoke her words slowly, enunciating each syllable as if speaking to a child: “My remarks were addressed to my companions, and not to you. If I did not discover by your language that you must be ignorant of all the laws of good breeding, I should take the number of your company and report you to your commanding officer to be punished for your impertinence.”

The Senate doorkeeper, recognizing Rose as a gallery regular, rushed to her side. “Madam,” he said, “if he insults you, I will put him out.”

Rose smiled, holding her shut fan over her heart. “Oh, never mind,” she whispered. “He is too ignorant to know what he has done.”

The next time she saw the Union officer, she swiped a finger across her throat and mouthed the word “beware.”

She sent another message to Beauregard, this time on her mourning stationery, heavy white paper with a black border—a visual that mirrored her warning about the strengthening of fortifications around the Capitol. “McClellan is vigilant,” she concluded. “There is little or no boasting this time.”

She continued to take her daily walks. Every eye in the city seemed fixed upon her, every gesture weighted with meaning. There was something strange about the tilt of the washerwoman’s basket and the way the young man stood on the corner, twirling his cane. She no longer found the surveillance humorous; even an elderly gentleman sitting on a park bench roused her nerves. “To me,” she said, “his manner of polishing his glasses, or the flourish of the handkerchief with which he rubbed his nose, was a message.”

She received a peculiar note—peculiar because it came from the city post office, an unlikely route for her Confederate connections to use. The note began: “Lt. Col. Jordan’s compliments to Mrs. R. Greenhow. Well, but hard-worked . . .” The rest of the page had been torn away. To protect herself, she showed it to Senator Wilson during his next visit and hid it inside a vase on her mantel for safekeeping.

She prepared another report for Beauregard, noting that “McClellan is very active and very discreet,” and sent it by way of a courier named Bettie Hasler, who never questioned Rose and had no idea of the impending danger.

One morning, an old friend and sometime informant, Anson Doolittle, appeared at her door. He was a relative of Wisconsin senator (and friend of Lincoln) James R. Doolittle and, according to Rose, “an occasional and useful visitor to my house.” Doolittle handed her a letter addressed to a colonel in Richmond and asked if she would send it.

It was not an uncommon request. The Confederate States of America had established a Post Office Department back in February, but the Federal government initially maintained service throughout the Southern states. In May, the Confederate postmaster general assumed control but encountered immediate difficulty. Pickup and delivery were thwarted by Lincoln’s blockade, the presence of Union troops, and the increasing scarcity of postage stamps. While Doolittle could easily mail a letter in Washington, DC, he had little guarantee of proper delivery to Richmond. His most reliable option was to entrust letters to those able to cross Union lines: officers on furlough and sick leave; slaves who could hide mail inside baskets of food or clothing; or well-connected individuals like Rose, whose network facilitated daily communication between Washington and the surrounding Southern states.

Doolittle sweated in the heat of her parlor, waiting for a response. For the first time during their long acquaintance Rose wondered who and what he was: another “friend” whose relationship with her took precedence over ties to the Union? Or maybe, just maybe, a double agent who found her company as useful as she found his?

She finally said, “McClellan’s excessive vigilance has rendered communication almost impossible, but you might leave it and trust it to chance.”

Doolittle thanked her and showed himself out. Over the next several days he called to see if she’d sent the letter, but Rose was “always very sorry that no opportunity had occurred.”

In her next missive to Thomas Jordan she warned that General Hiram Walbridge, a former New York congressman and friend of Lincoln, was a spy, and indicated that she was under surveillance: “Do not talk with anyone about news from here as the birds of the air bring back. But I wish I could see you as I know much that a letter cannot give. Give me some instructions. You know that my soul is in the cause. . . . Tell Beauregard that in my imagination he takes the place of Cid,” a reference to El Cid, the military hero in medieval Spain.

She signed off with “Always Yours, R.G.,” an incendiary choice of words in an era when “Ever your friend” was a customary closing among the betrothed.

She was certain, now, that the strange men were Yankee detectives. “I was slow to credit,” she confessed, “that even a fragment of a once glorious government could give to the world such a proof of craven fear and weakness as to turn the arms, which the blind confidence of a deluded people had placed in their hands, for the achievement of other ends, against the breasts of helpless defenseless women and children.”

She began urging secessionist friends, couriers, and sources—including John C. Breckinridge, the former US vice president, and William Preston, former minister to Spain—to leave the city before the Yankees could apprehend them. She wasn’t going anywhere, at least not yet; there was still much work to do and fewer people to do it. She now had to undertake missions herself, meeting her spies on selected street corners to deliver information, which they would then pass on to Beauregard. But she took new precautions, practicing how to hide information in places she hoped the Yankees wouldn’t dare look. She spent hours at her Singer “Grasshopper” sewing machine, fastening a pearl-and-ivory tablet on a silver chain and other contraband for Confederate soldiers into the voluminous quilted underskirt of her gown. She stitched maps of fortifications into the lining and cuffs, and slipped the latest about General McClellan behind the laces of her corset, pulling the notes tight against her body. She sat before her mirror and shook loose her hair, hiding secrets inside the twists and folds. The words from the message she’d received just before Manassas played inside her mind: Let them come.

She was ready for them.