Elizabeth Van Lew’s family flag.

(Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

When searchers retrieved Rose’s body from the Cape Fear River, they found a note meant for her youngest daughter:

You have shared the hardships and indignity of my prison life, my darling; and suffered all that evil which a vulgar despotism could inflict. Let the memory of that period never pass from your mind; Else you may be inclined to forget how merciful Providence has been in seizing us from such a people.

Rose O’N Greenhow

Little Rose was devastated by her mother’s death. “Les larmes de la pauvre enfant ne tarissaient pas [The poor child’s tears never stop],” wrote the mother superior of the Convent du Sacré Coeur. The girl, now eleven and a half years old, asked to be baptized so that she might be better equipped to pray for her mother’s soul. After the war Little Rose returned to the states, married William Penn Duvall, a lieutenant with the US Army, and had a daughter of her own.

In 1888, the Ladies’ Memorial Association—locally organized groups of Southern white women dedicated to reburying the scattered remains of Confederate soldiers—marked Rose’s grave with a marble cross. It was engraved with the words MRS. ROSE O’NEAL GREENHOW. A BEARER OF DISPATCHES TO THE CONFEDERATE GOVERNMENT, a tribute that remains to this day.

Emma’s memoir was an unqualified success, selling 175,000 copies; in comparison, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the greatest publishing phenomenon of the nineteenth century, sold 300,000 when it came out in 1852. Before the war Emma had spent her Bible salesman’s salary on an elegant horse and buggy, but now, uninterested in her newfound wealth, she instructed her publisher to donate all proceeds to the sick and wounded soldiers of the Army of the Potomac.

When the war ended she was thrilled by the ubiquitous sight of the “dear old Stars and Stripes,” but, like everyone else in her adopted country, found herself unsure of what to do next. Linus Seelye, her fellow Canadian and friend, had left Harpers Ferry to attend to his pregnant wife back home in Canada, and she was restless for something new. She headed to Oberlin, Ohio, and briefly took classes at Oberlin College, noted for being the first fully coeducational and racially integrated American institution of higher learning. But after the excitement of war she found the academic life “too monotonous,” and decided to go back to Canada herself, the first time she’d been there in seven years.

Much had changed since her last visit home, that cold fall day when she had appeared as Frank Thompson, surprising her mother and praying her father wouldn’t walk through the door. Both Betsy and Isaac had died during the war without ever knowing what had become of their youngest child, and family legend has it that Emma’s father spent his final years sitting and staring out the window, waiting for her return.

She spent that summer in New Brunswick, hunting with her brother Thomas and taking long, solitary walks through the woods, and when the weather turned she decided to go back to Oberlin. On the way she passed through Saint John, where Linus was living and working at his brother’s carpenter shop. He was now a widower; his daughter had died in infancy, and his wife six months later. He followed Emma to Ohio and asked her to marry him. She did, on April 27, 1867, at the Wendell House in Cleveland, a fashionable hotel where Lincoln had stayed en route to Washington for his inauguration six years earlier. As happy as she was with Linus—a gentle and genteel man who behaved nothing like her father—she couldn’t help viewing marriage, on some level, as a personal defeat. “Well,” she said, “you know how the census takers sum up all our employments with the too easily written words ‘married woman.’ That is what I became; and of course that tells the entire story.”

The couple had two boys, Linus and Henry, both of whom died in infancy, and a girl, Alice, who survived; Emma was thirty-two now, with faltering health, and she knew her daughter would be the last child she bore. When she learned through her church of two recently orphaned brothers, Freddy and Charles, an infant and a toddler, she and Linus took them in as their own. Through her church she also learned of an orphanage in St. Mary Parish, Louisiana, home to sixty-seven children, including many whose fathers had died while serving in the “colored” regiments of the Union army. They moved south so that Emma could manage the orphanage, but the muggy Louisiana climate stirred up old ailments. She suffered another bout of the malaria she had contracted during General McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign, so many years ago. She recovered, but soon afterward her daughter came down with measles. Six-year-old Alice died on Christmas morning of 1880, the third child Emma had lost in eleven years. She hid for weeks in her darkened room, unable to get out of bed.

Hoping for a fresh start, the family moved to Fort Scott, Kansas, a booming military outpost and home to numerous Civil War veterans—all of whom, Emma realized, were collecting pensions for their service. She thought of her recurring malaria, her left leg that still ached and throbbed, her foot that was so deformed she had trouble fitting it into a shoe. She was, she decided, entitled to the same compensation. No matter that the War Department still officially denied that women had served in the Union Army disguised as men. Or that even if Emma proved she was Private Frank Thompson, he was listed on the service rolls as a deserter and therefore ineligible for a pension. She would both clear Frank’s name and make sure he got what he deserved.

First thing Monday morning, February 20, 1882, Emma sent a notarized letter to the Michigan adjutant general, John Robertson, swearing that she and Frank Thompson were one and the same, and that she had used that alias to enlist.

Robertson, coincidentally, had recently finished his tome Michigan in the War, which included a passage about the mysterious brigade postmaster who went AWOL:

In Company F, 2nd Michigan, there enlisted at Flint Franklin Thompson (or Frank, as usually called) aged twenty, ascertained afterward and about the time he left the regiment to have been a female, and a good looking one at that. She succeeded in concealing her sex most admirably, serving in various campaigns and battles of the regiment as a soldier; often employed as a spy, going within the enemy’s lines, sometimes absent for weeks, and is said to have furnished much valuable information. She remained with the regiment until April 1863, when it was supposed she apprehended a disclosure of her sex and deserted at Lebanon, Kentucky, but where she went remains a mystery.

The adjutant general duly sent Emma her certificate of service.

Next, she had to solicit support from her former comrades. She decided against contacting Jerome Robbins; she needed the testimony of men who had served alongside her without knowing her secret. She thought of Damon Stewart, her bunkmate at the start of the war.

She took a train to Flint, Michigan, where, more than twenty years earlier, she had lived and worked as Frank Thompson and dated many of the belles in town, all of them also now married and middle-aged. She found Stewart’s dry goods store, the tinkle of the bell announcing her entry. Adrenaline scoured her mouth dry and muted the pain in her foot. She hadn’t seen Stewart since the Battle of Williamsburg in May 1862, when she hauled him off the field and tended to his wounds. He had been sent home and later reenlisted with another Michigan regiment, and she wondered what he’d heard about Frank Thompson’s strange disappearance in the spring of the following year.

Now he rose from his desk, approached, and asked how he might be of service.

She found her voice—Emma’s, not Frank’s. Stewart had never heard it before. “Can you by chance,” she said, “give me the present address of Franklin Thompson?”

Stewart was silent, letting his eyes drift up her body and halting at her face, shadowed by the veil of her hat. Behind the veil she bit her lip, forbidding a smile.

“Are you his mother?” he asked.

The past two decades had settled hard on her, carving lines around her eyes and giving her a heavy, seesaw gait. She forgave her old friend his mistake.

“No,” Emma said, “I am not his mother.”

Stewart tried again, perplexed. “His sister, perhaps?”

The bell chimed behind them, and they were no longer alone.

Emma plucked the pencil from Stewart’s hand and took a card from the counter. Hastily she scribbled a few words and watched as he read: “Be quiet! I am Frank Thompson.”

He wilted into a chair, looking at Emma as though seeing her for the very first time, and in that she found a small victory. “She was as tranquil and self-possessed,” he said, “as ever my little friend Frank had been.”

Stewart and other old comrades rallied behind her cause, writing affidavits attesting to her identity, good character, and valiant service during the war. They enlisted the support of two members of Congress: E. B. Winans of the Sixth Michigan district, who served on the Committee for Invalid Pensions; and Byron M. Cutcheon of the Ninth district, a former major with the Twentieth Michigan who now sat on the Committee of Military Affairs. The latter man remembered “Frank Thompson” well, especially his bravery under fire during the Battle of Fredericksburg. He offered to sponsor legislation to remove the deserter charge from Emma’s records, while Winans sponsored a bill to grant her a soldier’s pension.

President Chester A. Arthur signed the pension bill on July 5, 1884, granting Emma $12 per month, but Cutcheon’s desertion bill languished before passing, finally, in July 1886. In the meantime Emma had become both a celebrity and a curiosity back home in Fort Scott, Kansas. Neighborhood children whispered that Mrs. Seelye had been a soldier and spy during the war and made a game of spying on her, peeping around trees to watch as she wielded an ax and chopped wood in her yard, wearing men’s trousers and army boots. They whispered about her short hair and worried she might cut off their ears. A neighbor and fellow veteran spoke to the kids on Emma’s behalf so they would no longer be afraid of her. “She may have been the means of saving the lives of many soldiers,” he said. “A spy does save many lives.”

Emma died on September 5, 1898, at the age of fifty-six, finally succumbing to malaria. She was buried in La Porte, Texas, where she and Linus had moved to be near their adopted son Freddy, but in 1901 her fellow members of the Grand Army of the Republic—the nationwide Civil War veterans group—had her remains moved to the Grand Army of the Republic burial ground in Houston’s Washington Cemetery following a proper military funeral. Back in Michigan, Jerome Robbins clipped and saved an obituary of his old friend. A “most remarkable character,” it read, “has passed away.”

Belle Boyd gave birth to a daughter, Grace, in mid-1865, a few months after the South surrendered. To supplement the sales from her memoir (and to keep herself in the public eye), she pursued her dream of stardom on the stage. Coached by the American actress Avonia Jones and the English Shakespearean actor Walter Montgomery, she made her debut on Friday evening, June 1, 1866, at Manchester’s Theatre Royal, playing Pauline in Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s romantic comedy The Lady of Lyons. The reviewers were largely favorable but noticed an odd timidity in her performance—surprising, one mused, for a woman who “has faced shot and shell” and “led by the nose some very astute Federal officers.”

Belle Boyd on the lecture circuit, circa 1890.

(South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum)

Samuel Hardinge seldom attended his wife’s performances, instead spending his evenings with a courtesan named “Fannie Sinclair,” and Belle decided to leave her “utterly worthless” husband. Taking advantage of President Andrew Johnson’s proclamation of amnesty to most former rebels, she and her baby daughter returned to the United States, where she filed for divorce in a New York courtroom. She told reporters she wanted no alimony, and was only anxious to be rid of both her husband and his name. On the day the divorce was finalized, she wore a strand of bells around her neck, and from that point forward she told anyone who asked that Samuel Hardinge had died.

She continued her theatrical career, billing herself “Belle Boyd, of Virginia,” sometimes riding onto the stage on horseback and improvising scenes from her memoir. In 1868 she gave a reading in Washington, DC, and invited Lincoln’s former bodyguard, Ward Hill Lamon, to attend. Early the following year, after a performance in New Orleans, a fan approached and asked her to dinner. A month later they married in a French Quarter church. This husband, like her first, was a Yankee: John Swainston Hammond, an Englishman by birth, immigrated to America and served with the 17th Massachusetts Infantry. Their son, whom Belle named Arthur Davis Lee Jackson in honor of her favorite Confederate heroes, was born in January 1870 at an insane asylum in Stockton, California, where she had checked in after her mind “gave way.” He died in infancy and was buried there. “Her feet and brain had no rest,” one reporter sympathized. “We cannot admire, but we must pity this strange soul, and be astonished at its wild, romantic career.”

By the fall, Belle’s doctor declared her “recovered” and she, John, and Grace moved from city to city, never staying in one place long enough to call it home. They had three more children: a son, John, and two daughters, Byrd and Maria Isabelle, nicknamed “Belle” after her mother. For fifteen years the elder Belle did not appear onstage, but still the spotlight followed her. Like Mark Twain she was reported dead. After it became clear that such reports were greatly exaggerated, she began hearing of a host of impersonators.

The Masonic lodge in her hometown, Martinsburg, issued a warning that a stout brunette, calling herself Belle Boyd, had been “imposing herself on the fraternity throughout the South.” In Philadelphia a female swindler using Belle’s name devised a primitive version of a check-cashing scam. Belle and her family had scarcely arrived in Texas when she learned that someone was appearing at opera houses in tiny towns nearby, telling stories of her exploits as the Spy of the Shenandoah. “Belle Boyd, the Confederate Spy, who died recently,” wrote one Austin periodical, “is living in Corsicana, Texas, in easy circumstances. She is also living in a garret in Baltimore, where she makes a scanty living by needlework, so the papers say. Belle is beating her Confederate record of being in two places at once.” Another impostor—or was it the genuine Belle?—confronted an Atlanta newspaper editor for calling her a fraud, carrying a Smith and Wesson in one pocket and a derringer in the other.

The real Belle Boyd, meanwhile, felt her mind giving way again, betraying her and rousing terrible old ghosts. She told a reporter she’d been subjected to “private sorrows which the world should not demand.” In October 1884, when she was forty, she shot and wounded one of nineteen-year-old Grace’s suitors for “ruining” her daughter, and then disowned Grace, calling her “dead to the family.” That same month, she discovered that her husband had a second wife. She promptly divorced him until he divorced his first wife, and then remarried him. John, in turn, accused Belle of having her own affair. They headed back to divorce court, both of them claiming to be the plaintiff. Grace, despite their differences, took Belle’s side, telling the court that her father “boxed Mamma’s ears” and barraged her with insults, at least one of them “reflecting on her chastity.” Their divorce was final on November 1, 1884. Less than six weeks later, Belle took a third husband. Nathaniel Rue High was an actor and only twenty-four, sixteen years her junior.

Nathaniel encouraged Belle to go back to work, as he alone couldn’t support three children. She briefly gave elocution lessons before returning to the stage, reenacting her wartime adventures. She debuted in Toledo, Ohio, on Sunday evening, February 28, 1886, her costume a nod to both genders: a rebel soldier’s belt, an elaborate plumed hat, and a specially designed brooch featuring an enameled Confederate battle flag. The debut was, Belle said, an “unqualified success,” although that didn’t stop her from seeking other means of revenue—namely an unsuccessful $50,000 lawsuit against the Chicago Tribune for accusing her of failing to pay her bills.

Belle took her show on the road, incorporating Byrd and Belle Jr. into the act, giving readings as far west as Iowa, and renaming her performance The Perils of a Spy. At veteran reunions, she led thousands of rebels in reenactments of her favorite battles, recounting the time she leaped through the fields with the agility of a deer, rushing to tell Stonewall everything she knew. She was again reported dead, this time confused with Belle Starr, the notorious western outlaw who was fatally shot in February 1889. She took to carrying affidavits from the Grand Army of the Republic and Confederate Association attesting that she was “authentic” wherever she performed.

In the coming decade her crowds dwindled, even in the South; the people who had lived through the war were dead or dying off. She was destitute, often unable to pay for housing on the road, but somehow found a way to buy Eliza, her long-devoted servant, a high chair and plate for the birth of her first grandson. As they had during the war, both admirers and detractors commented on her appearance and skillful manipulation of her femininity; she was a relic from the near past who deftly played both lady and killer. “She stood there looking at the dead Union soldier and in that moment she was no longer a child,” wrote the Washington Daily News. “Life had been crinoline and the smell of roses . . . now . . . . Belle hardened into a strange frightening being.”

In a late interview, Belle herself characterized her life as if it were one long sin that needed to be confessed—with one pointed exception. “I have lied, sworn, killed (I guess) and I have stolen,” she said. “But . . . I thank God that I can say on my death bed that I am a virtuous woman. . . . Fortune has played me a sad trick by letting me live on and on.” On June 11, 1900, at the age of fifty-six, she died of a heart attack in Kilbourn, Wisconsin (now Wisconsin Dells), after giving a reading at the local Methodist church. The Women’s Relief Corps of Kilbourn, an auxiliary of the Grand Army of the Republic, chipped in to pay for her burial, and her pallbearers included four veterans of the Union army. On that day, at least, there were no impostors taking her name, wearing military dresses with gilded buttons and trailing trains, caricaturing her character. She was Belle Boyd, the one and only, and fortune’s sad trick was done.

A few days after the fall of Richmond, Elizabeth rode in her carriage—pulled by her last remaining white horse—through the wreckage of her city to the state capitol, now headquarters of Union general Godfrey Weitzel. There she found several papers once belonging to abolitionist John Brown, including his constitution, which denounced slavery as “a most barbarous, unprovoked, and unjustifiable War,” and which she would keep for the rest of her life. After Lincoln’s assassination, she took some small comfort in watching the Union army repair bridges and roads and clear away the rubble, taking with it all evidence of the rebel government, including ninety-one boxes of archives.

In a letter to the War Department, Benjamin Butler praised Elizabeth for furnishing “valuable information during the whole campaign” and requested that John Van Lew be allowed to come home from Philadelphia. She had joyous reunions with her brother and numerous members of the Richmond Underground who had fled in the final months and weeks of the war. Mary Jane Bowser returned too, taking a job teaching two hundred black children at a newly established school in the Ebenezer Baptist Church; she would go on to teach in Florida and Georgia. In November, General Ulysses S. Grant, accompanied by his wife, Julia, visited Richmond during a brief tour through the South. He barely stopped to shake hands with local officials but spent an afternoon drinking tea with Elizabeth on her veranda, in full view of the neighbors, who would never forgive her for what she had done. “She had no moral right to speak of the people of the South as ‘our people’ and as ‘we,’” wrote one. “She had separated herself from us. And, the women of the South being so loyal, so self-sacrificing, so devoted, she made herself not only notorious but offensive. She was vain enough to imagine that she was called upon to make herself a vicarious sacrifice.”

Thirteen days after being inaugurated as president, Grant nominated Elizabeth as postmaster of Richmond, one of the highest federal offices a woman could hold in the nineteenth century. It was also one of the most lucrative, paying up to $4,000 per year, and she desperately needed the money. She had depleted a large portion of her estate during the war, spending thousands on food and supplies for Union soldiers and bribes for Confederate officials, and hinted to her Northern contacts that compensation would be welcome. The head of the Bureau of Military Intelligence, George Sharpe, campaigned on her behalf, writing a letter to Congress in which he declared that “for a long, long time, she represented all that was left of the power of the US government in the city of Richmond.” Nevertheless Elizabeth received only $5,000, one third of what she wanted. Her brother’s hardware business was in such dire straits that she wrote to Grant begging him to employ John, as well: “I earnestly entreat you will give him a position which will enable him to make his living, something which our community has refused to permit him to do—He is an earnest & faithful Republican.” And unlike Rose, Emma, and Belle, she refused to write a memoir, believing that to do so would be in “coarse taste.”

Southern newspapers vehemently opposed Elizabeth’s appointment—one opined that Grant had chosen a “dried up maid” who planned to start a “gossiping, tea-drinking quilting party of her own sex”—but she began her work unfazed, moving into the Custom House building downtown, where Jefferson Davis once kept an office on the third floor. Post offices had long been bastions of male privilege (“respectable ladies” were encouraged to avoid them altogether and send servants to pick up the mail) and she set about changing the culture, slowly and methodically, in her own way and time. She requested that Virginia newspapers refer to her as “postmaster” instead of “postmistress” and hired numerous female postal clerks, including her friend Eliza Carrington, whose seamstress had been an integral part of the Richmond Underground. She also employed black postal workers, among them her family’s former slaves—a practice that, in the tumultuous atmosphere of Reconstruction, made her unpopular even among some Unionists.

President Grant remained loyal and retained her during his second term. As she had during the war Elizabeth refused to wilt under the increased scrutiny, and flung her behavior in the faces of her critics. She spoke publicly about “the thirst for knowledge among our colored citizens” and sponsored a library for them. Before the presidential election of 1876 she sent an impassioned plea to Northern Democrats, printed in both Washington and Richmond newspapers, urging them to repudiate their counterparts in the former Confederacy. She spoke of votes rigged against Republicans, of Southern whites who still wielded whips, of the “gross personal insults” she constantly endured. She signed off with a lament about her own disenfranchisement. “As a woman,” she wrote, “I have no power but through your vote.” When her beloved mother, Eliza, died, she couldn’t find enough pallbearers to carry the casket. Neighbors ridiculed her service, calling it the “nigger funeral.”

After the election of Rutherford B. Hayes, a moderate Republican who promised to end Radical Reconstructionism—the idea that blacks were entitled to the same rights and opportunities as whites—Elizabeth had to fight to keep her job. Her opponents called her erratic, eccentric, mentally unstable, and masculine; any vigorous attempts to defend herself only seemed to prove them right. In May 1877, Hayes replaced her with the moderate William W. Forbes, who at least kept many of her black and female hires.

Elizabeth mourned the loss of not only her position and influence but also her income. Her efforts to sell off various family properties proved fruitless. No one in Richmond would even give her a fair mortgage on the mansion. She put it up for sale, thinking she would never again sit by the fireplace that hid her dispatches or peer into the secret room, but each offer was too insulting to accept. She sought out her old friend Ulysses S. Grant. “I tell you truly and solemnly I have suffered,” she wrote. “I have not one cent in the world. . . . I am a woman and what is there open for a woman to do?” She asked Grant if he might persuade current president James Garfield to make her postmaster again. Grant agreed, but his efforts were in vain.

At last Elizabeth retreated, withdrawing entirely from public life. She had no target for her ferocious will. Her one political act was to attach a note of “solemn protest” to her annual tax payment, declaring it unjust to tax someone who was denied the vote. In 1890 she watched as her city erected a sixty-one-foot-tall statue of Robert E. Lee on horseback before a roaring crowd of 100,000. She felt there was no place and no one left for her. Her brother John had moved and was living with his second wife and their children on a farm in Louisa County. He died in 1895 at age seventy-five. His older daughter—her niece Annie—lived with her husband in Massachusetts. Eliza, the younger niece, was all she had, and a strange distance had come between them—the sort of fraught, crackling distance that can come only from being too close. Eliza had never married and still lived with her in the mansion. The same neighbors who had shunned Elizabeth, who had warned their children away from the parched, wizened old lady with the sharp blue eyes and curled, clawlike hands, also grew wary of her niece. The daily rejection and isolation wore at Eliza; they were no longer welcome even at St. John’s Church, since Elizabeth had made a habit of barging in late and disrupting the service. The pastor had taken to locking the doors once all of his regulars were inside. She told her aunt that if she had a child and it became a Republican she would kill it rather than watch it suffer her same fate. She cleaned the mansion with a grim, manic energy, flitting like a hummingbird among its fourteen rooms. If Elizabeth tried to stop her Eliza turned on her in fury, ordering her to leave.

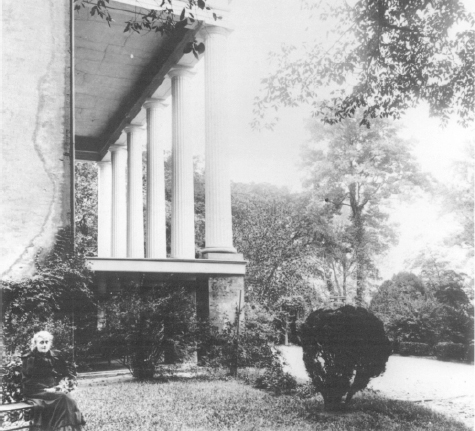

Elizabeth Van Lew (bottom left) in the garden of her mansion, circa 1895.

(Valentine Richmond History Center)

Terrified, Elizabeth obeyed, spending hours wandering the city, aware of every person who crossed the street to avoid catching her eye. She began gathering relics of her life, piece by piece, and donated them to the poor: the exquisite china and fine silverware, the antique furniture, the family photos in gilded frames. The famous backyard gardens grew tangled and overgrown, years of planning and care undone. Eliza cleaned and cleaned. Elizabeth asked for one favor: that she leave up the decorations from their last Christmas together, in 1899. In the spring of the following year Eliza became unexpectedly and severely ill, and died on the tenth of May. Elizabeth had hovered by her bedside, weeping, “Save her! Save her! I love her better than anything in the world.”

Richmond waited for Elizabeth to follow. In August she read her own obituary, complete with pictures of herself and Ulysses S. Grant and tales of her espionage during the war. “They say I am dead?” she asked a reporter. “Well, I am not, but I am very feeble and sick. My heart is heavy and I am sad. My hours are lonely and long.” She died on September 25, 1900, at age eighty-two, and was buried in Shockhoe Cemetery, across from the graves of her parents. Because the family plot had insufficient space, her casket was positioned vertically in the ground. A group of abolitionist admirers in Boston, including Colonel Paul Revere—the grandson and namesake of the Revolutionary War patriot—raised money for a memorial stone:

SHE RISKED EVERYTHING THAT IS DEAR TO MAN—FRIENDS—FORTUNE—COMFORT—HEALTH—LIFE ITSELF—ALL FOR THE ONE ABSORBING DESIRE OF HER HEART—THAT SLAVERY MIGHT BE ABOLISHED AND THE UNION PRESERVED.

Soon after her death, the people of Richmond—adults and children alike—began reporting sightings of the ghost of “Crazy Bet.” She haunted her own home, now owned by a civic organization, casting the outline of her figure against the basement walls, scaring the servants to death: “I done hear Miss Lizzie walkin’ ’bout,” one said. “I knowed all ’long she was here.” The city condemned the mansion in 1911 and had it torn down the following year, but Elizabeth’s ghost still stalked the streets. Parents warned their children, “Crazy Bet will get you” if they misbehaved.

The sightings continued as late as World War II. In 1943, one Richmond woman, out for a walk with her young son, felt a cat brush against her leg. Suddenly the cats were everywhere—Elizabeth was rumored to have dozens—and then the woman heard the soft rustle of taffeta. When she turned she saw her: Elizabeth, in a black Victorian dress, a beribboned hat perched upon her head, her face like dried fruit beneath its brim. The ghost waved her hands and spoke in crisp, urgent tones. “We must get these flowers through the lines at once,” she said, “for General Grant’s breakfast table in the morning,” and with the push of the wind she was gone.