For a period of thirty-three hours, from just before dawn on April 12, 1861, to mid-afternoon the following day, sleep was hard to come by, in both North and South. In Manhattan, Walt Whitman left the Academy of Music and strolled down Broadway, where he heard the hoarse cries of the newsboys: “Extry—a Herald! Got the bombardment of Fort Sumter!”

Passersby broke into small groups under the brightly blazing lamps, each huddled around a paper, unable to wait until they got home to read. So it was true: the Confederates had opened fire on Fort Sumter, a federal fort in South Carolina, the first shots of the first battle of the American Civil War.

In Charleston, so close to the awful roar in the harbor, ladies solaced themselves with tea and a firm faith that God “hates the Yankees” and was clearly on their side. In Washington, DC, President Lincoln, in office barely six weeks, prepared to call 75,000 volunteers to quell this “domestic insurrection.” One hundred miles away, across the rolling Virginia countryside, the citizens of Richmond celebrated and cried, “Down with the Old Flag!” Within the week they got their wish: Virginia became the eighth state to join the Confederacy, with vessels in the James River flying not the Stars and Stripes but the Stars and Bars. By early June the South had added three more: Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee.

The new enemy countries settled into a war that many predicted would be over in ninety days. The twenty-three Northern states had 22.3 million people to the South’s 9.1, nearly four million of them slaves whom their masters dared not arm. Jefferson Davis, former U.S. senator from Mississippi and new leader of the South, moved his pregnant wife and three children to the Confederate capital of Richmond. He was more prescient than most, expecting “many a bitter experience” before all was said and done.

Troops poured into the two rival capitals and began making themselves into armies. Morning brought the reveille of the drum; night, the mournful notes of taps. Nothing was seen, nor spoken of, nor thought of but the war. There was work for everyone to do, even the women—especially the women. They had to adjust quickly to the sudden absence of fathers and husbands and sons, to the idea that things would never be as they had been. They had no vote, no straightforward access to political discourse, no influence in how the battles were waged. Instead they took control of homes, businesses, plantations. They managed their slaves in the fields, sometimes backing up orders with violence. They formed aid societies, gathering to darn socks and underwear for the soldiers. To raise money for supplies they hosted raffles and bazaars, despite widespread resistance from the very men they aimed to help (protested one general, “It merely looks unbecoming for a lady to stand behind a table to sell things”). They even served as informal recruiting officers, urging men to enlist and humiliating those who demurred, sending a skirt and crinoline with a note attached: “Wear these, or volunteer.”

Some—privately or publicly, with shrewd caution or gleeful abandon—chafed at the limitations society set for them and determined to change the course of the war. In the pages that follow I tell the stories of four such women: a rebellious teenager with a dangerous temper; a Canadian expat on the run from her past; a widow and mother with nothing left to lose; and a wealthy society matron who endured death threats for years, and lost as much as she won. Each, in her own way, was a liar, a temptress, a soldier, and a spy, often all at once.

This is a work of nonfiction, with no invented dialogue. Anything that appears between quotation marks comes from a book, diary, letter, archival note, or transcript, or, in the case of Elizabeth Van Lew, from stories passed down by her descendants—details about her incredible operation that have never before appeared in print. Characters’ thoughts are gleaned or extrapolated from these same sources. In any instance where the women may have engaged in the time-honored Civil War tradition of self-mythology, rendering the events too fantastic, I make note of it in the endnotes or in the narrative itself.

Beneath the gore of battle and the daring escapades on and off the fields, this book is about the war’s unsung heroes—the people whose “determin’d voice,” as Whitman wrote, “launch’d forth again and again,” until at last they were heard.

Karen Abbott

New York City

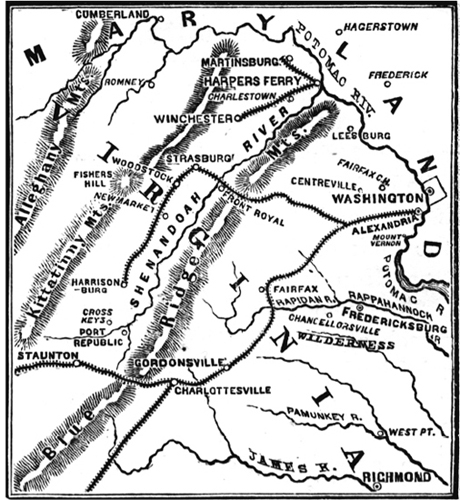

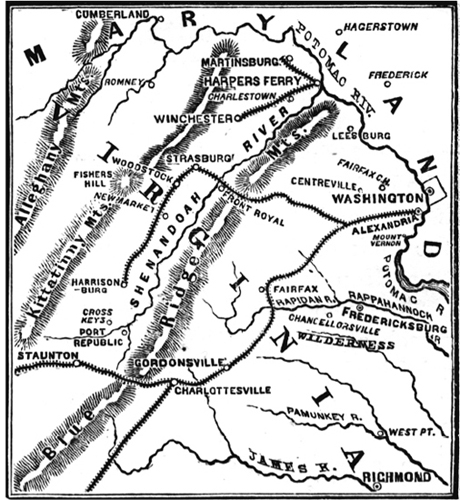

Shenandoah Valley, 1861.

(Courtesy of the Florida Center for Instructional Technology, fcit.usf.edu)