A Lazy Susan on a table in Burns Ranch House. HERITAGE PARK, CALGARY, ALBERTA

COME ’N’ GET IT celebrates the early days of cattle ranching in western Canada. Whether in a chuckwagon on the range or in the ranch-house kitchen, the people who prepared meals for hungry cowboys, ranch hands, family, and friends were a hardy bunch who knew how to make the most of what they had. This book pays tribute not only to the food of the early times, but to the lifestyle and wonderful hospitality of the ranching community.

Cattle ranching in British Columbia had its beginning in the Cariboo gold rush. The miners who struggled into that rugged and remote area were prepared to put up with great hardships, but they drew the line at a steady diet of beans. They wanted meat.

A few enterprising men organized cattle drives, with up to five hundred head at a time, from the western United States to the Cariboo. There the animals were quickly sold for a profit. When gold petered out, the remaining cattle formed the nucleus of some of the great cattle ranches of today.

A Lazy Susan on a table in Burns Ranch House. HERITAGE PARK, CALGARY, ALBERTA

The correct riding attire—a jacket, skirt or trousers, boots, gloves, and hat. At the turn of the century, “ladies” rode sidesaddle, both legs on the same side of the English-style saddle. GLENBOW ARCHIVES, NC-39-241

The North West Mounted Police set the stage for ranching in Alberta and Saskatchewan. They provided a market for beef and developed a peaceful relationship with the First Nations. Grazing leases were cheap, and ranchers could turn cattle out on the open range to feed on the nourishing prairie grasses. Powerful ranches were formed: the Cochrane, the Bar U, Oxley, Walrond, Matador, and others.

Food supplies were transported over great distances and had to be stored for weeks and months. The supply list was simple: flour, sugar, coffee, beans, rice, oatmeal, dried fruits, canned tomatoes, molasses, corn syrup, yeast cakes, baking soda, salt, and a few spices.

A typical diet for a small ranch without a cook was “plenty of hot biscuits, fried salt pork, beans or rice, stewed prunes for dessert and lots of corn syrup.”

If large, the ranch employed a cook, whose job was to feed the ranch hands. The cook at the Bar U went out of his way to look after the boys. Every Sunday morning he left the house with his willow pole and bits of red fabric to tie onto a fishing hook. He waded into Pekisko Creek and threw in his line once for each man that he had to feed. It is said he never missed and that every Sunday morning there was a fish fry in the cookhouse.

In the early days the cooks were men, but as more women came West, they eventually took over the task. As the character and size of ranches changed, so did the method of working. Women were expected to participate in the running of the ranch, as were the children. Ranchers butchered their own animals, corned beef, ground sausages, smoked bacon, saved drippings for cooking or making soap, preserved fruit, and prepared jam. Large gardens produced vegetables for canning, pickling, and storing in the root cellar. Bread, buns, pies, and cakes were baked at home.

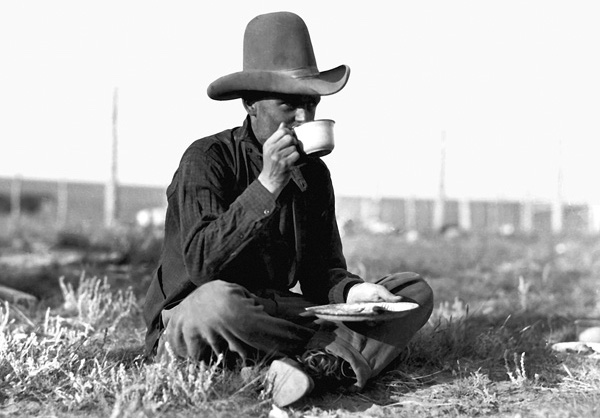

A cowboy finds a quiet place for a meal durning a cattle round up, circa 1920. GLENBOW ARCHIVES, NB-H16-452

During the devastating cold winter of 1906–07, thousands of cattle froze to death, bringing economic disaster to the owners. The completion of the railroad brought settlers wanting farmland and barbed-wire fences. A new generation of ranchers emerged, usually with less money and land but with more experience and a different style of ranching. However, that part of the ranching story is for others to tell.

Generally, ranch people were thrifty and self-reliant. They were proud of their ability to produce and prepare food from their land. They remain so today.

Ranching no longer dominates the Canadian West, but it remains an important industry. Its traditions of simple, gracious living, love of the outdoors, and a spirit of freedom and adventure are revered today. And an appetite for old-fashioned ranch foods remains hearty.

The recipes and stories for this book were collected from letters, diaries, manuscripts, history books, family cookbooks, and personal interviews with ranching families. There have been many enjoyable occasions and extraordinary instances of hospitality offered during my research: an invitation sight unseen by the Osbornes to their lovely ranch home nestled near old Fort Walsh; a viewing of Laura Parsonage’s private collection of pioneer-ranch-house artifacts; dinner with Dorothy Blades on an old-fashioned ranch table with a swinging Lazy Susan centre; a day with Bert Sheppard at the OH Ranch and an invitation to his eightieth-birthday party; a visit with Meriel Hayden; lunch and pemmican at Jean Hoare’s and a view of Willow Creek, where the bull trains camped overnight a hundred years ago; Fred McKinnon’s introduction to his fabulous family; a visit to the Commercial Hotel in Maple Creek; a fall drive through the beautiful Cariboo country.

My sincere thanks to all who provided information and to the helpful staff of the many museums and archives that I visited.