Chapter 1

Arguments and ancestors

Naum Kleiman

I am quite sure that all Eisenstein enthusiasts could contribute to the subject that I address today. If this introduction is rather pointilliste in character, this is because my basic aim is to provoke thought. There has been a new impetus in Eisenstein studies and this is not only due to the anniversary of his ‘ninetieth birthday’. There have been many changes in our world, many changes in our cinema and in the relationship between cinema and the other mass media as well.

Paradoxically, our image of Eisenstein is also changing all the time. The most positive aspect of this whole process is that he has not yet been canonised. We can still argue about him. Indeed he does not allow himself to be canonised. I would draw your attention to the ending of one of the chapters in his unfinished book of essays, People from One Film, which has as yet been translated into very few other languages.1 Here he describes the group working on Ivan the Terrible and there is a passage about Esfir Tobak, who was helping him with the montage. It is called ‘The Ant and the Grasshopper’. At the very end of this chapter Eisenstein makes a very curious remark. He recalls his theories, the declarations which had resounded over the years, and at the end he says that it never occurred to anyone to check whether the author of these statements actually followed his own theories.

Unfortunately we sometimes try to illustrate his theories too directly with examples from his films, or to understand his films as a direct realisation of his theories. But, as I am now beginning to understand, his practical work is on the one hand richer than his theory, while his theory is on the other hand so much richer than his body of work. They do not merely correspond: indeed sometimes they conflict with one another. Some of the ideas that he expressed as hypotheses are substantiated in his work, while others are not substantiated at all.

We should not lose sight of the fact that he worked over a span of twenty-five years and many changes occurred during that time. There were not only political and social changes in the Soviet Union. The first thing we must do is to dispose of the notion that Eisenstein followed closely these political and social changes or reacted to the pressure they put upon him in his working career. Of course they are of enormous significance: indeed we must make more of an effort to understand the context in which his work unfolded, because we just do not know enough about that period.

At the same time, however, there are many immanent processes, both in his development as an artist and as a theoretician which we must understand. Eisenstein referred again and again to the enormous influence upon him of Professor Sukhotsky, his teacher at the Institute of Civil Engineering in Petrograd. But we know very little about Sukhotsky, although he is one of the most interesting figures in Russian culture at the beginning of the twentieth century.2 Sukhotsky was one of the first to grasp the importance of Eisenstein’s theories and one of the first to understand the new study in physics of the infinitesimal and to explain its poetic significance. Eisenstein recalls that it was Sukhotsky who taught him the theory of the limits to which objects aspire. If we take this on trust from Eisenstein then we can see that many of these theoretical statements represent limits towards which his work aspires. But remember that in his Memoirs he was always referring to King Gillette and this idea that you have to make a half turn of the screwdriver back from the limit towards which you aspire when talking in terms of your own practice. It is this half turn backwards that gives you the whole range of stylistic and even individual variables. We have not studied this relationship between the limit and the concrete variable adequately. Let me give just a few examples.

One of the most frightening things that Eisenstein ever said in his arguments with Dziga Vertov was, ‘It is not a “Cine-Eye” that we need but a “Cine-Fist”’.3This statement has given rise to a mass of speculation. When we were celebrating Eisenstein’s anniversary, the philosopher Yuri Davydov gave a speech that was very critical of Eisenstein, arguing that he had been a kind of Stalinist who had wanted to take this ‘cine-fist’ and crush people’s skulls with it, as distinct from Brecht who, by contrast, had stimulated independent thought. This image of the ‘cine-fist’ comes from Gorky’s Reminiscences of Lenin where he recalls Lenin’s remark that when you listen to Beethoven you feel like stroking people’s heads when what you ought to be doing is thumping them with your fists. However, Eisenstein would say that he wanted to use this fist ‘to plough over the audience’s psyche’.4

Of course you can interpret that as an attempt to intrude violently on people’s thinking but, if you look at it in the context of what he was writing at the time, you will understand what he is really saying. For instance, in his notebooks on Bekhterev, which have unfortunately not yet been published, he remarks that art must change the conditioned reflex that is provoked by the social context and, in particular, the audience must be diverted from reflex reactions of servility and terror.5 The idea that people have not merely an instinct but also a psychological reflex towards fear and servility and that we must free them from both is a very important one, especially in the context of the situation in the Soviet Union at present. If you look at Eisenstein’s work, that is the direction in which it is going, people ridding themselves of their automatic reaction of fear when they are faced with violence and terror.

From The Strike right through to Ivan the Terrible both the subject and the structure of the films can be seen as a kind of inoculation against this reflex reaction of panic and fear. Of course that raises the question of Eisenstein’s so-called sadism: is he really a sadist? Perhaps, on the contrary he is trying to give us a kind of inoculation against sadism. I will come on to Eisenstein’s personality later but it is already clear that the kind of brutality that appears in his work had nothing to do with any kind of sadism per se. That is one example of where we have to re-examine our established views. Let me give you another: Eisenstein’s ideas on acting in cinema.

Eisenstein made many statements criticising the so-called ‘academic’ acting school and it is known how much he built on ‘types’ in cinema, in both his films and his theoretical teachings. In actual fact the entire Proletkult collective acted in The Strike. In The Battleship Potemkin a few Proletkult actors were joined by more from the Odessa actors’ union. Almost all the characters in the Odessa Steps sequence are actors. In October many of the actors came from the Leningrad union. Even the procession with the cross in The General Line was made with actors from October because both films were made at the same time. There are far more actual actors than ‘types’. So we have to understand how he worked with actors as ‘types’ and with his ‘types’ as actors.

Let me give another example to illustrate this relationship between theory and practice. His first article, ‘The Eighth Art’, written with Yutkevich, is very much a criticism of German Expressionism and he criticised it again later, but once more the situation is also more complex.6 The impact of Expressionism on Ivan the Terrible has already been researched.7 The word vyrazitel’nost’ (expressiveness) was one of Eisenstein’s favourite words. We have discovered a note which again has unfortunately not yet been published but is certainly worth summarising here. It is the only note that Eisenstein made while editing The Battleship Potemkin. The provisional title is ‘Acting with Objects and Acting through Objects’: it is incomplete but he makes a very interesting observation that, whereas in theatre you have acting with an object, in cinema you have acting through an object.8 In Potemkin he gives the name ‘everyday Expressionism’ (bytovoi ekspressionizm) to the method in which the external aspect of the object is unaltered but various expressive schemas are deployed to place the object in different contexts. This ‘everyday Expressionism’ is partly a contrast to, and partly a continuation of the object. It is unusual for Eisenstein but it does make us understand all his statements much more clearly.

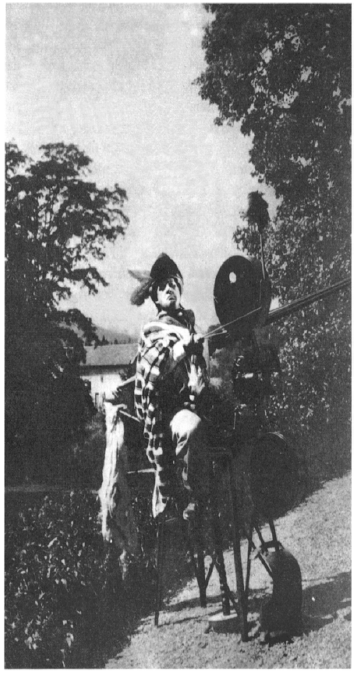

The next matter that I want to raise is the context of Eisenstein, which is really much broader than we have ever suspected. Take the theory of influence: who influenced whom? When we are looking for influences we search for similarities and traces. But I should like to propose a somewhat different model here. There are a number of well-known photographs from La Sarraz of Eisenstein as Don Quixote, sitting on a horse and holding a camera and a pike in his hand. He is comparing himself to Don Quixote. I believe we can make an analogy here with Pushkin who always had the image at the back of his mind of himself as a knight in shining armour at a tournament. This is important because a knight is prepared to take up a challenge and fight in a tournament. So, when we talk about the Byronic influence in Pushkin I think it is more a question of Pushkin being prepared to take up the Byronic challenge, to ‘fight it out’ with Byron, rather than just passively accepting Byron’s influence. The same is true of the relationship between Pushkin and his teacher Zhukovsky or his friend Vyazemsky.

Eisenstein felt as if he were constantly engaged in a tournament, and of course the medieval ideal was that the tournament was not a war but a friendly contest. This started with his ‘tournament’ with Meyerhold, which led to such battles as the one that raged around the production of Puss in Boots.9 One of Eisenstein’s favourite expressions was ‘Me too’, but it is not just a question of ‘Me too’ because his other favourite expression was ‘That’s wrong’.10 This is dialectics in the classical sense of the word, the possibility of fighting while seeing the other side of the question as well. So when we look at the context of who his teachers were, who his friends were, we can see how much broader it is than we are used to thinking. The exhibition showed his fascination with Constructivism and Cubism, how important these were for him, for instance in his drawings for Picasso’s ‘Parade’. At the same time, we must remember that he was a child of Symbolism, the Russian Symbolism of Blok, Bely and Ivanov, and the echoes of this can be traced right through to the end of his life. For instance, there was intended to be an epilogue to Alexander Nevsky, which was an integral part of the film. Unfortunately Stalin’s personal censorship excised the death of Alexander Nevsky from the film but the finale, the victory over the Tartars at Kulikovo Polye, is taken directly from Blok.11 Throughout Eisenstein’s life we can find both conscious and unconscious elements of the epoch that formed him and from which he emerged. This is also true of Nikolai Evreinov, the writer, director and theorist of theatre.12 We must remember Evreinov’s influence when we talk about Joyce and ‘inner monologue’ and the influence that all that had on Eisenstein.

But there are even more unexpected contexts for Eisenstein: there is, for instance, the so-called commercial cinema. Until now we have underestimated the influence of such hits as The Exploits of Elaine, The Grey Shadow and Fantômas, but they were very important.13 Alan Upchurch was looking at the cover of the first edition of the Fantômas book, recalling the scene in Feuillade’s film in which the criminal world is peeping out of a barrel, and he immediately thought of that scene in The Strike where the strikers peep out of a barrel!14 These ‘tournaments’, or tunnels, that link the cultures of different countries are very important for our understanding of Eisenstein. If one remembers the scene in the Valley of Death at the end of Greed, Eisenstein’s scenario for Sutter’s Gold begins with that same scene.15 This is no coincidence: it is just a continuation and a reexamination of the same phenomenon from another country and another historical context. Or take a famous case like that of Chapayev.16 In the 1930s it was the accepted view that the ‘psychological attack’ of Chapayev exceeded that of the Odessa Steps sequence. So then Eisenstein depicted an attack in Alexander Nevsky to demonstrate to his students just how a psychological attack could be made. But he went further than this in jousting with his students who were beginning to turn away from him. There is a scene in Chapayev where potatoes are used to show where the commander should be and a scene in Ivan the Terrible where, in response to the tragic Vladimir Staritsky, Ivan says ‘The Tsar must always be in front!’ I think that this is an answer, not only to Chapayev, but also to his own pupils as to where the leader should be. It is also, apart from anything else, a profoundly autobiographical moment.

I have to leave out so many things here but I feel I must say something about what we might call his ‘ancestors’, rather than his immediate predecessors or advisers. We already have very stereotyped views about the importance of Zola, Leonardo da Vinci and so on. But why do we pay so little attention to Ben Jonson whom Eisenstein regarded as his teacher? Jonson’s theory of humour and his linear dramaturgical composition were very important to Eisenstein. We also completely ignore the influence of the medieval mystery plays. We in Moscow have just finished reconstructing Eisenstein’s article on Gogol and the language of cinema, which is a sort of complement to his Pushkin articles. Eisenstein is saying that Gogol is his parent as well as Pushkin. One thing that he does not mention in that article but which is perfectly clear is that the image that he used in Bezhin Meadow when Stepok, who is already mortally wounded, falls from a height, has three stages, three separate shots, and it transpires that this is a direct reference to a scene in Gogol’s Taras Bulba, because there is a passage in which Eisenstein discusses the moment when the father shoots the son and the son falls like a sheaf of wheat that has been cut. If you think of the biblical imagery in Bezhin Meadow, of the image of wheat falling on the ground, you can see how important this is.

Another very important factor is Eisenstein’s own personality, which we need to discern more clearly now. There used to be just the legends that surrounded him in the 1930s but now new legends are appearing. I suppose it is natural that any great artist has legends growing up around him. For instance the image now emerging is of Eisenstein the conformist, the faithful student, who only went beyond the bounds of the orders that were issued to him because he was a genius. The evidence cited for this is his decision to produce Die Walküre.17 However it is not the case that he agreed to produce Die Walküre because he was afraid. In fact we now know a lot more about the production, as a result of new research on it. I have myself noticed how gingerly we approach a subject which seems to us to be ethically ambiguous! But when we grasped the nettle and opened up the files on Die Walküre we found that it was an anti-fascist treatment of a subject that the fascists regarded as fascist in itself. It was compassion and humanity that shone out from Eisenstein’s interpretation. You can imagine that the theme of compassion was not exactly the top priority at the end of the 1930s.

There are many prejudices that we have to shed when we approach his work and there are whole fields that we have not even begun to touch. We know very little about Eisenstein’s theatre work and I welcome Robert Leach’s contribution on this subject.18 The subject of Eisenstein’s ethics has also suddenly emerged. The fact that ethics is a very ambiguous word in itself is important to our work. We must include it alongside our purely cinematic research. His teaching work is also a very important part of our research.

We can see from all this how much more publishing lies ahead. In the first instance that is our responsibility. It is our responsibility and our fault in the Soviet Union that so little of Eisenstein’s work is being published and so slowly. I think that the most important things we should be preparing for publication now are his diaries and also the definitive text of Non-Indifferent Nature 19 and the Method which is something that is beginning to take shape. The twelve volumes that we hope to publish in the Soviet Union will not cover everything but at least they will provide us with a basis on which we can hope to build.20

The time has now come for us all to work together. Perhaps the time has also come for a dream to come true and for us to set up an International Eisenstein Society. I should like to conclude by mentioning the person who did more than anyone else to promote the understanding of Eisenstein, Jay Leyda. He dreamed of setting up such a Society and he was the first to make a contribution to it. I should like you to mark his memory.21

Translated from the Russian by Richard Taylor