Chapter 3

Eisenstein’s early films abroad1

Kristin Thompson

INTRODUCTION

The circulation of Eisenstein’s early films outside the Soviet Union is an important issue for at least two reasons. First, we would like to be able to gauge the conditions which allowed his films to influence other filmmakers. Second, the success that greeted Potemkin in particular seems to have had a significant impact on Soviet production practice, and almost certainly it made the radical montage style more acceptable to officials there.

I shall concentrate here on the 1920s, and particularly on Potemkin’s impact in Germany and the USA; these were the most important foreign markets in which Eisenstein’s films were given relatively successful commercial releases, and in both cases Potemkin paved the way for subsequent imports of Soviet films.

The standard account of Potemkin’s early career claims that only after the film became an enormous hit in Berlin did Soviet audiences become interested in it.2 One thing I hope to do here is put its German success into some perspective and briefly suggest what impact it may have had on Soviet film-making policy. In looking at Potemkin’s American career, historians have concentrated on the New York première and the film’s censorship problems. I shall try to flesh out such accounts by looking at how the film entered the growing art cinema market in America and played successfully in smaller American cities. Finally, I shall conclude with a very brief set of examples suggesting that Eisenstein’s early films quickly became classics, being revived in a variety of situations, running from art cinemas to 16mm screenings by leftist workers’ groups.

My focus is thus selective, but I hope to suggest at least one general conceptual point. From our modern perspective, historians often tend to create a split between commercial films and avant-garde films, with the assumption that avant-garde films tend not to be popular successes. Yet the 1920s was a decade during which the alternative institutions of the art cinema were just beginning to be created. To a surprising degree, stylistically radical films made in France, Germany, the Soviet Union and other countries were produced, distributed and exhibited successfully within existing commercial cinema institutions. Eisenstein’s films demonstrate how the Soviet cinema was seen abroad in a variety of institutional situations.

BIG BOX-OFFICE IN GERMANY

Of all major foreign markets, Germany was the most sympathetic to Soviet films, and it provided the conduit through which many such films passed to other countries. Potemkin was far more successful in Germany than in any other foreign market, and it was the one Soviet film which prepared the way for exports.

Prior to Potemkin’s Berlin première in April 1926, most Soviet films had failed to penetrate the German market. In mid-1922, one of the famine documentaries was shown, being reportedly the first Soviet film to appear in Germany.3 Father Sergius showed in early 1923, but the first Soviet film to achieve commercial success in Germany was Polikushka, in March of that year.4 Polikushka was released by Germany’s leading film company, UFA, and the film’s popularity was apparently due primarily to the performance of its star, Ivan Moskvin.

Polikushka did not, however, create a general interest in Soviet films in Germany. Other Soviet films were released over the next two years, without notable success. These included The Palace and the Fortress, The Cigarette Girl from Mosselprom, Aelita and The Station Master. Although these were trade-shown in Berlin, only The Station Master seems to have had any commercial distribution, probably due mainly to Moskvin’s continued popularity.5

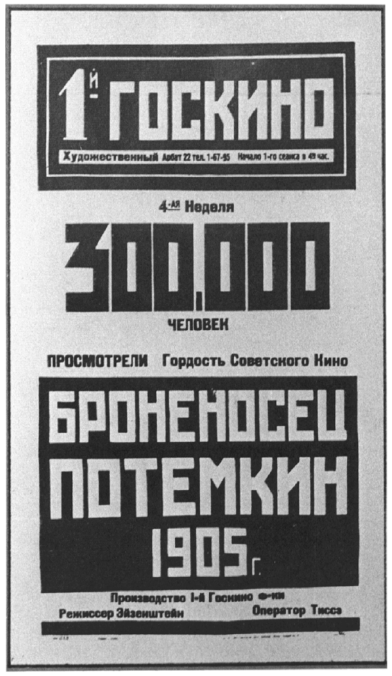

Potemkin’s spectacular career in Germany changed the situation considerably. The film’s initial censorship difficulties in late March and early April of 1926 are familiar enough not to need outlining here. With cuts totalling about one hundred feet, the film was passed for public exhibition on April 10.6 It premièred on 29 April at the Apollo Theatre in Berlin and met with unprecedented success. By mid-May the film was in general release and played all over Berlin, repeating its initial success and selling out consistently.7 A description from the Berlin correspondent of the Parisian arts journal Comædia suggests how intense Potemkin’s impact was on the intelligentsia:

It is no exaggeration to say that over the last three weeks, the Russian film Battleship Potemkin has revolutionized Berlin. Every stranger who disembarks and asks what there is to see in the capital of the Reich is invariably told: ‘Go see Battleship Potemkin.’ Nothing else is discussed in the salons. In the course of the season which is ending, not a single film, not a single play has approached the success of this Bolshevik propaganda film, which is showing simultaneously in twenty-two cinemas in Berlin.8

To put this statement in context, the total number of cinemas in greater Berlin in 1925 was reported in one source as 342 and in another as 382.9 In the provinces, Potemkin repeated its initial success, with sold-out houses in Frankfurt, Mannheim, Dresden, Dusseldorf, Hamburg and other German cities.10

The question remains as to how big Potemkin’s German success really was and how it affected Soviet production and export. There are indications that Potemkin was an enormously popular film in Germany, perhaps even the top box-office hit of the 1925–6 season. Heinrich Fraenkel, the German correspondent for The Bioscope, reported in July that Potemkin had ‘achieved by far the biggest box-office success of the last season in Germany’.11 Other sources support this claim that Potemkin was the top grosser of the German season, which would have lasted from September 1925 to May 1926. An article in Comædia, published in August 1927, summarised the past two seasons in Berlin:

Last summer, the cinematographic season in Berlin ended with the triumphant success of a Russian film, Battleship Potemkin. Several weeks later, the next season began with the triumph of an American film, Ben Hur. No German film has attained anything like the success of these two foreign works.12

Prometheus, Potemkin’s German distributor, ran an advertisement for its Soviet releases for the 1926–7 season, proclaiming: ‘We brought you the greatest box-office hit of the past year, Battleship Potemkin.’13 Difficult though it is to imagine from a modern perspective that Potemkin could be a hit comparable to Ben Hur, it would seem that this was the case in Germany at least.

The film’s German success quickly led to sales in other foreign countries. As of 1 July, the Soviet Trade Delegation in Berlin reported that Potemkin had already made $20,000 for Goskino within Germany. Deals had been made with other foreign countries, guaranteeing the following minimum fees: Austria, $2,500, Czechoslovakia, $3,500, Scandinavia, $4,000, the UK, $16,000.14 By the autumn of 1927, Potemkin had reportedly been sold to thirty-six different countries, a record second only to that of The Station Master, with thirty-seven.15 By spring 1928, Eisenstein’s film had slipped to fourth place among Soviet exports, with sales to thirty-eight countries.16

The question remains as to what these figures imply about Potemkin’s actual success and its impact on Soviet film policy. I would like to make a few suggestions on these topics, though these must necessarily be very tentative and speculative. If we assume that Potemkin sold to nearly forty foreign countries, and that a conservative estimate of the average price for the distribution rights would be around $3,000 per country, it seems possible that the film brought in over $100,000 through these sales. In Germany alone, Goskino’s share of the grosses was $20,000 for the first two-and-a-half months of Potemkin’s release; although the film was temporarily withdrawn during its second major censorship battle in July, it then continued to circulate in Germany for at least a year. There was no other foreign market where Potemkin enjoyed this degree of success, but it seems conceivable that the film’s total income abroad was in the range of hundreds, rather than tens, of thousands of dollars. Clearly Potemkin brought a considerable amount of money to Sovkino.

In early 1928, Konstantin Schvedchikov’s report on the film industry of the Soviet Union stated that before the 1926–7 season, Soviet films as a whole made no profit, and that they brought a profit of about 10 per cent in the 1926–7 season.17 Variety, in outlining the Schvedchikov report, gave the average cost of production for a Soviet feature as $35–40,000.18 It is virtually impossible to determine equivalencies between dollars and roubles for this period, but the Variety figure at least seems plausible; an average feature film made in Western Europe at this time would typically have cost in this same range. Rough though these estimates must be, it seems probable that Potemkin made back its costs several times over.

Moreover, it must have done so in a remarkably short time. In late 1926, a study of Soviet production declared that films typically took a long time to amortise their costs: often twelve to sixteen months, occasionally as long as two years. Given that Potemkin’s first Soviet run was in January of 1926 and its German success began in April, it may well have begun to make a profit within six months of its release.19 Potemkin also created a fascination with Soviet films in Germany. Over the next few years dozens of films were imported, and many were successes—though few achieved anything like the popularity of Potemkin.

It is not surprising, then, that the exportation of Potemkin and the Soviet films that followed it seems to have galvanised the Soviet industry. At the beginning of 1927, the Lichtbildbühne stated that the success of Potemkin abroad had been used ‘to secure new capital for state film production’.20 In a 1927 interview, Alexander Ivanovsky, director of The Palace and the Fortress, credited the recent exportation of films to Germany and the USA with permitting the Soviet industry to import lighting equipment; such importation finally solved what had been a major problem for the studios.21

In mid-1927, the Moscow correspondent of the Lichtbildbühne wrote an article which reflects a major change in official Soviet policy in the area of film-making. This article is worth quoting at some length, in part because it singles out Eisenstein for special mention:

We have witnessed a remarkable process here. Film, which has by no means held a great interest for the Soviet authorities, has suddenly advanced into the centre of attention. This change has been caused especially by the enormous success of the Russian film in Germany, which has been reported by all the newspapers in glowing terms. While previously little attention was paid to the fiction film, and the interest in film in the departments of Lunacharsky (People’s Commissar for Education, etc.) was almost solely in the educational film for the peasant population, the fiction film has now gained a political attractiveness. I had the opportunity to speak with a person who is also well known in Germany, which is particularly interested in the political effect of the Russian film. I was told:

‘We have had no money for amusements. As long as the fiction film meant nothing in our public affairs, we could not allow ourselves the luxury of film production. Moreover, and we do not wish to deny it, we made many mistakes in the production process and did not always approach the right people. Now circumstances have completely changed. The success of our films abroad has shown us that they represent the artistic and spiritual resources of our people and that they create a sort of silent, nonpolitical propaganda for Soviet Russia. That makes it worthwhile for us to raise film production to a new, high level, which in turn makes substantial expenditures urgent. If you watch the work in the studios, you will notice that it has less to do with political propaganda films than with cultural propaganda. We want to serve Russian art, naturally without being able to interfere in the private lives of our artists by making rules concerning the types of work they do.

It is a fact that political subjects are declining. The die-hards, like Eisenstein, naturally will not swerve from their concerns. Eisenstein’s plans are aimed, after all, exclusively at producing films that display the lives and sufferings of the Russian people, free from all constraints of acting and aesthetic construction. He wants to work again without stars, heroes, or “romance”’.22

It is hard to imagine this remarkable description of the new policy in the Soviet film industry being given even a year later than mid-1927. Still, it gives some indication of Eisenstein’s importance in that industry and suggests how Potemkin’s foreign success helped make the radical style of the Soviet montage films acceptable to officials.

Eisenstein’s other works were among the many Soviet films that made their way to Germany in Potemkin’s wake. Recent accounts suggest that The Strike was a complete failure in Germany in 1927. I have, however, found a number of contemporary references to the film indicating that it may have done average business.23 October was more successful, premièring as Zehn Tage, die die Welt erschütterten on 2 April 1928. It ran for three-and-a-half weeks, until 26 April; at that point it went into general release and was booked into 120 Berlin theatres.24

It was Potemkin, however, that remained the touchstone film for the Germans. Later Soviet films were often compared to it, and most were found wanting. For example, about one third of the Lichtbildbühne’s 1927 review of Room’s The Bay of Death was actually devoted to Eisenstein:

Every time that a new Russian film arrives here, its première is eagerly anticipated, and we hope for a new revelation of Russian film art. Eisenstein’s Potemkin—not its political themes but its cinematic artwork —again becomes alive for us and compels comparisons with its elementary power. For us, Eisenstein has become a landmark of everything that is distinctive in Russian film. And we can only state once again: He came to us too early! Had we not seen his Potemkin yet, we would take a number of Russian films shown here recently and, on a purely artistic basis, would perhaps have evaluated them differently than we have actually done.25

On the other hand, had it not been for Potemkin, many of those films might not have reached Germany at all.

EISENSTEIN’S FILMS IN THE USA

Potemkin was a breakthrough film for introducing Soviet cinema into the USA as well. Although a few Soviet films had been shown prior to Potemkin’s première in late 1926, none of them had been seen widely or had been commercially successful. After that première, American interest in Soviet films gradually increased.

The relation of Potemkin’s American release to the founding of Sovkino’s American branch, Amkino, in November of 1926 still needs to be researched, but it is clear that there was a connection. By June of 1926, Sovkino’s New York representative, Leon Zamkovsky, was reportedly holding trade shows of Potemkin in New York, looking for an American distributor.26 For example, it was shown to an invited group on 31 August, where distributors were reportedly dubious about the film’s commercial prospects.27 These trade shows failed to find a distributor for Potemkin. Possibly partly as a result, in November 1926, Amkino was formed; during that month, the American première of Potemkin was announced for early December, at the Biltmore Theatre in New York.28 Amkino was to distribute the film in the USA.29

During the 1920s, it was extremely difficult for imported films to break into the American market. It was therefore common practice for a foreign company that hoped to find American distribution to rent a theatre in New York and hold a première run, usually hoping that the film’s success would attract a distributor. According to a Variety report published four weeks after Potemkin’s 5 December première, Amkino had apparently paid an unusually high rent for the Biltmore but still did better business than it had expected. Still, Amkino was apparently reluctant to gamble on the film’s success beyond four weeks, when an American entrepreneur took over:

‘Potemkin’, the Russian special feature picture at the Biltmore, New York, has extended the booking another four weeks. The film sponsor is guaranteeing $5,000 weekly for the bare walls but is said to have shown a profit.

Starting this week and for the remainder of the engagement, ‘Potemkin’ is under the management of Ralph Shoflar. It appears the Russian management did not care to take a chance on the extended booking.30

Shortly after Potemkin’s New York première, Zamkovsky described in an interview how Amkino ‘was founded for the purpose of purchasing motion picture equipment and also of acquainting the American public with the production of Russian studios’.31

That process proved to be only gradual, but Soviet films did make headway in the American market. Potemkin was the only film Amkino released in the USA during 1926. It premièred two in 1927: Polikushka and The Legend of the Bear’s Wedding.32 The number of Soviet releases increased in later years, however, with eight in 1928 and twenty-one in 1929.33 Moreover, a small number of Soviet films were released in the USA by independent distributors; mostly notably, in 1928, HammersteinSelwyn distributed The End of St Petersburg, The Golden Dawn and The Mother.

One reason that Potemkin and subsequent Soviet films succeeded in the USA is because their releases coincided with the rise of the institution of the art cinema there. The first successful organisation in America devoted to showing artistic films, especially imports, was Symon Gould’s Film Arts Guild. The Guild was founded in 1925 and in the spring of 1926 it began holding regular screenings in the Cameo Theater in New York.34 Over the next few years, a series of similar small cinemas opened in other American cities. Initially their staple fare consisted largely of German imports, but during the late 1920s and early 1930s, they increasingly showed Soviet films as well.

Such cinemas provided a small but enthusiastic intellectual audience for Soviet films outside New York City. During 1927, Potemkin and its successors did well in such venues. In Washington, DC, for example, Potemkin drew crowds at the newly-opened art house, the Little Theatre. Variety described how Eisenstein’s film ‘not only had the customers lined up for a block, but had every allowable standing room space filled practically every show’. Despite its tiny 225-seat capacity, the Little grossed a respectable $2,000 in Potemkin’s short two-and-a-half day run.35 Potemkin was the first film shown when Chicago’s Playhouse went over to an arthouse policy in September of 1927; as Variety put it, ‘First week of house’s conversion to people with brains; $5,400; looks like it has a good chance’.36

Potemkin consistently did well in New York, being revived at the Cameo several times. In September of 1927, Variety reported: ‘Around three or four times now, but management thinks well enough of it to hold over’.37 It became a standard double-feature item for the Cameo, showing with The Last Laugh in mid-1928 and again with Ivan the Terrible (i.e., Wings of a Serf) about a month later—each time to average business.38

The Cameo, under the management of the Film Arts Guild, held the première New York runs of many Soviet films, and other little cinemas soon appeared. New York’s third art-house, the Fifty-Fifth Street Cinema, opened in mid-1927 with The Legend of the Bear’s Wedding.39 Late that same year, New York’s Fifth Avenue Playhouse Group opened branches in various American cities; its Cleveland house, the Little Theatre of the Movies, showed Potemkin as its first feature.40 When the Little Carnegie Playhouse opened in the autumn of 1928, the American première of Ten Days That Shook the World was among its first presentations.41 The film did good business there and ran for four weeks.42 It quickly moved to the Cameo for a second run at the end of 1928.43

I should note in passing that not all Soviet films played only in arthouses. A few made their way into regular commercial cinema theatres. Potemkin, for example, played a down-at-heel Baltimore theatre in the spring of 1927; Variety’s inimitable prose describes how local intellectuals turned out in droves:

The Embassy furnished the box-office sensation last week. Just about the time the public had forgotten the location of this house and local film people were wondering when the crepe would be hung on the door the long-neglected ticket machines began grinding out pasteboards so fast that the ticket-seller’s dress was scorched by the overheated machinery. ‘Potemkin’ was the magnet.44

Such scattered clues in Variety suggest that Soviet films, by Eisenstein and others, made their way beyond Broadway, and that they were often successful in other cities in the USA.

INSTANT CLASSICS

I have concentrated on the commercial successes of Eisenstein’s early films, but of course they met with censorship and other obstacles in many foreign countries. Nevertheless, they also had a broad impact that cannot be gauged by commercial popularity alone. I would like to close by emphasising that the contemporary impact of these films did not end with their first screenings in various countries. In those places where they were allowed to be shown, they typically became classics at once. This often meant, as we have seen with the US market, that they were revived in art and repertory cinemas; in addition, in some countries, left-wing groups circulated them extensively. I shall give a few examples of such practices here.

Not surprisingly, revivals of Eisenstein’s films quickly occurred in Germany. In April of 1928, the newly-opened Kamera cinema, Berlin’s first art house, ran Potemkin for one week; this revival was apparently timed to coincide with the première of October.45 Various local branches of the main socialist cinema club in Germany, the Volksverband für Filmkunst, sponsored screenings of Soviet films by Eisenstein and others.46

In the Netherlands, a leftist group called the Institut voor Arbeidersentwikeling gave a number of screenings of various films during the 1927–8 season, showing Potemkin 137 times.47 In Britain, where censorship problems delayed the releases of Eisenstein’s early films for years, the extensive network of film societies and workers’ clubs meant that the Soviet classics eventually were widely seen. For example, the Workers’ Theatre Movement formed a 16mm distribution section called KINO in December of 1933. The first print acquired, of Potemkin, paid for itself in the first two months of bookings, and the group went on to acquire The General Line. By the winter of 1935, KINO had nine Soviet features and various shorts in distribution; another London distributor, the Progressive Film Institute, had films by Eisenstein and other Soviet film-makers available in 35mm.48 In 1934 and 1935, the Forum Cinema in London held Soviet film seasons, including Potemkin, October and The General Line.49 In the USA, according to Russell Campbell, Soviet films such as these were shown in 16mm in rural areas during the 1930s by small leftist groups like the Farmers’ Movie Circuit.50

These brief examples should suggest, as I indicated at the outset, that Eisenstein’s films, though part of what we would now consider an avantgarde movement, drew upon a wide range of cinematic institutions for their dissemination abroad. Some of these institutions were overtly commercial, while others were anything but. As a result, even though the films were banned in many countries, they managed to reach a surprisingly large and heterogeneous audience, ranging from Berlin’s intellectual elite to farmers in the USA.