Chapter 4

Recent Eisenstein texts

INTRODUCTION: EISENSTEIN AT LA SARRAZ

Richard Taylor

Eisenstein’s attendance at the Congress of Independent Film-Makers, held in the rather unlikely setting of the château of La Sarraz in Switzerland in September 1929, is well known but not well documented. We know that he was accompanied by his assistant Grigori Alexandrov and the cameraman Eduard Tisse and that the Congress was also attended by Walter Ruttmann, Hans Richter, Béla Bálazs, Léon Moussinac, Ivor Montagu and Alberto Cavalcanti among others. We know that one of the highlights of the Congress was the impromptu production of a film, The Storming of La Sarraz, a rather light-hearted allegory depicting the triumph of independent cinema over commercial dominance.1

The film however was accidentally lost and only tantalising photographs remain showing Moussinac as D’Artagnan or Eisenstein as Don Quixote. Until recently it has also seemed that no record of the discussions had been kept either. It appeared that one of the most extraordinary meetings of minds in the history of cinema had to all intents and purposes been lost to posterity.

Fortunately that was not after all the case. Naum Kleiman, whose knowledge of the Eisenstein heritage is unparalleled, has recently uncovered two manuscript sources in the TsGALI archive in Moscow, where the Eisenstein papers are held. Both manuscripts were written in German: one comprised the notes Eisenstein made for his La Sarraz speech while still in Berlin and the other was a fuller version that was written up when he returned to Berlin after being expelled from Switzerland as an undesirable alien. Kleiman has used his extensive experience of Eisenstein’s writing method to combine the two manuscripts and the version that follows, ‘Imitation as Mastery’, is the result of that combination.

We cannot of course know whether Eisenstein did actually deliver the speech in this form at La Sarraz, just as we do not know for certain whether the Congress film ever existed: Hans Richter for one suspected that Eisenstein had told Tisse not to load the camera because they did not have enough money to pay for the film, but then others have alleged that Richter himself lost the film canisters on a train. But ‘Imitation as Mastery’, whether delivered or not, marks an important stage in the development of Eisenstein’s thought at a time when he was still savouring the first excitement of his prolonged stay abroad and when the advent of sound, which he had left the Soviet Union to study, seemed to many to threaten the old film world, both in its theory and its practice, with complete collapse.

Eisenstein had reacted to protect the centrality of the montage concept in his own theory of cinema just over a year earlier with the celebrated ‘Statement on Sound’, first published, interestingly enough, in Berlin.2(It was Eisenstein who actually wrote the ‘Statement’ and it really represents his views, but Pudovkin and Alexandrov signed it too.) Montage, the ‘Statement’ argued, must be applied to sound as well as image: the threatened dominance of the ‘talkie’, where sound was used merely to illustrate the image, was but one alternative. Orchestral counterpoint, where the two conflicted, offered much greater potential.

Eisenstein devoted considerable attention to the problem of finding a common denominator between sound and image so that some kind of system of audio-visual montage could be elaborated: it was one of the main themes of his articles, ‘An Unexpected Juncture’, published in August 1928, and ‘Beyond the Shot’ and ‘The Fourth Dimension in Cinema’, both written in 1929.3 Without the achievement of such a common denominator, it would have been impossible to continue with Eisenstein’s developing notion of the ‘attraction’ in sound cinema and the whole idea of a non-linear narrative intellectual cinema would have foundered.

‘Imitation as Mastery’ represented part of Eisenstein’s attempt to avoid this fate and to look forward to the ideas he was to develop in his increasingly complex montage writings of the 1930s and 1940s. The central thrust of the argument, as Mikhail Yampolsky makes clear elsewhere in this volume,4 was that when art imitated reality it had to imitate not the reality of surface appearance (photographic reality) but the reality of inner essence (the essential bone-structure). That inner reality did of course include all the associations connected with the objects depicted in a particular sequence that gave those objects their quality of attraction and made them effective in an artistic (and also a political) sense. Two obvious examples from Eisenstein’s silent films would be the Odessa Steps sequence in Potemkin5 or the series of images of different deities in October.6 Sound added other layers to the bone-structure of the film and would provide the film-maker with an almost endless combination of possible uses for an increasingly sophisticated delineation of montage types. In ‘The Fourth Dimension in Cinema’ Eisenstein distinguished metric, rhythmic, tonal and overtonal montage as major groups.7 We can cite plenty of examples of his own attempts to use these various types of audio-visual montage from his two completed sound films, Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible. One obvious instance that Eisenstein himself analysed is provided by the Battle on the Ice in Nevsky, perhaps the most famous single example of his collaboration with Prokofiev.8

It is important to remember that sound did not represent for Eisenstein as it did for others a complete break with silent film. After all many theatres showing silent films had employed at least a piano accompanist and sometimes a full orchestra and the music they performed was not always mere improvisation. Edmund Meisel wrote specific scores for both Potemkin and October, which Alan Fearon has in recent years restored with the support of the British Film Institute. Nobody who has seen these films with the scores in live performance can doubt the influence that Meisel's music must have had on Eisenstein and the corresponding influence that Eisenstein’s ideas must have had on Meisel. There is a far greater continuity between Potemkin when performed in this version and the practice of orchestral counterpoint in sound film than is generally appreciated because the score brings out the inner essence of the images rather than merely illustrating their surface appearance.

The ability of cinema to extract this inner essence through the use of both sound and image, as in the examples cited above, confirmed for Eisenstein its potential superiority over other art forms. The construction of a film from units of attraction linked by a dialectical conflict between the inner essence of each unit rather than the superficial similarities between the external appearances of successive objects offered an escape from the impasse of linear ‘literary’ narrative, a way for independent film to storm more than the château of La Sarraz.

The concerns articulated in this ‘lost’ document have a far broader and more lasting relevance for art than the more famous lost film. Art should, in this view, be more than a mirror, just as it should be more than merely Trotsky’s hammer. ‘Imitation as Mastery’ confirms that Eisenstein was both a product of his time and a provocative and original thinker far ahead of it.

IMITATION AS MASTERY

Sergei Eisenstein1

Imitation…

According to Aristotle, the basic principle of artistic creativity.2

Like the creative urge itself therefore, also the key to mastery of form.

This basic idea of imitation as means to mastery crops up in the oldest ideologies, in the magic ideologies of the most ancient peoples.

The sun goddess of the ancient Japanese, Uzume, suddenly hides in a cave.3 The world is plunged into darkness. Prayers are to no avail….Even the gods are in despair. Then someone has the brilliant idea of holding up a mirror in front of the capricious goddess. Uzume’s likeness appears in the mirror. The goddess is plunged into self-contemplation and follows the mirror out of her dark cave…

That is how the mirror enters Japanese culture.

Catherine de’ Medici has her court magician make wax models of her enemies. Then she pokes out their eyes with needles. Cuts up their bodies and limbs. She does it to make them unhappy…. She does it only when she cannot, fortuitously, make these poor people unhappy in any other way!

Nowadays any old tart imitates her!

When her Fritz, Paul or Lude leaves her in the lurch, she cuts his photo across the face with her scissors. And tears his likeness to shreds.

There is no way in which the peasants of Normandy can be persuaded to have their photographs taken.

Caution is the mother of all porcelain dishes!

The tyrannical demi-urge of the Bible, Jehovah, knew that when he issued his first commandment, which was also [a] first prohibition: ‘Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image etc.’4

But this mastery, the magic one, is a mere fiction. Because magic imitation copies form.

And the event as such remains as intangible to it as the pale reflection in the empty mirror.

Nonetheless imitation is the way to mastery.

But imitation of what?

Of the form that we see? No!

Catherine de’ Medici needed a lot more than wax models to defeat her enemies.

Fritz meets his new Minne unscathed.

And the sun rises every morning whatever happens to go to sleep again in the evening.

No mirror is of any assistance in these cases! So—away with form as model! What then remains?

Principle remains.

Mastery of principle is real mastery of objects!

Principle or form?

Anyone who sees Aristotle as an imitator of the form of objects misunderstands him.

Like a cannibal.5 The idea of cannibalism runs deep as well. How, where and when does a drive like that arise?

‘Man is what he eats.’6

We read that every week in all the illustrated magazines! And that, it seems to me, conditions the instinct that drives us to consume our own likeness.

Our deep-seated instinct for self-preservation leads us to use as food what we ourselves consist of.

In instinctive primitive form there is however no distinction between external attribute, internal content and principle. It is all the same, so you eat what you see. If you eat your own likeness, you live forever.

This atavistic cannibalism is also evident in the highly intellectualised mythology of the Greeks.

Chronos (Saturn). Eternity. Immortality. …And Chronos…devours his own children.7

His likeness would be one. His children two. Is there a third in the mythology? What would remain? Devouring oneself after devouring one’s own children.

India has the god Brahma. The god is depicted sucking his own foot. The phallic symbol is crystal clear: Brahma, who is also the god of eternity and immortality, is devouring his own sperm. His own children. His own likeness. Something other. That is just a step-by-step development of the same principle.

Brahma represents it in all its clarity.

But…were the wretched Indians really so wrong? What was the starting point for the Steinach and Vorontsov method of rejuvenation?8 None other than self-fertilisation. The realisation of the symbolism of Brahma?

There is a great confusion between Brahma and Steinach, between different conceptions of the life-principle, caused by the false conception of the formal. Chronos. Cannibals.

Gilles de Retz, the child murderer: Retz too was seeking a means to eternal life.9 And he expected to find the solution through sacrificial offerings of his own likeness!

The sacrifice of one’s own image in the form of a human likeness in order to achieve eternal life: does not the same idea also lie at the basis of the Christian myth?…

So we have Steinach and Brahma. If the greatest mystery of immortality is addressed in this instance, then the most that medicine has to offer us is conceived in accordance with the same principles.

I was overwrought. Had a headache and so on. The doctor prescribed glycerine phosphate. I wanted to know what it was made of. Æsculapius explained to me that it was the same stuff that parts of the brain were made of…

How many people take blood cures…

How many mineral cures…

The age of form is drawing to a close.

We are penetrating matter. We are penetrating behind appearance into the principle of appearance.

In so doing we are mastering it.

Symbolism in myth is giving way to analysis of principle.10

Marx overthrows the magic of the cosmic concept through economics. He demonstrates how it is conditioned.

Marx does this through economics.

Marxism does it through history.

If you know how it is conditioned you can get right inside it. Make new history. Build a new life.

The burial-place of the pharaoh. Countless slaves. Oxen. Grain. Poultry. And it is all…painted! The difference between form and reality is nonexistent.

It is enough to draw all these things.

The pharaoh will have them with him in the other world as reality.

It is true. Nowadays half the world lives according to the same system. It sells, buys and sells again—objects that likewise only exist on paper. Nowhere more than in the film business.

But they call that speculation.

And it is one of those dishonest things!

Art is already familiar with the same phenomenon. First and foremost the art that is closest to real life: architecture and applied art.

In the dreadful era of art nouveau architecture too imitated nature. Houses stretched out like lianas (I almost said like Liane Haid!11). Balconies became flowers, lamps fruit, pillars became hunchbacked maidens, and so on. It needed the advent of a Le Corbusier, a Gropius or a Bruno Taut12 to show the way to imitate nature: to investigate utility, the principle of the structure of plants. To grasp the logic of the arrangement of the body, not to ape its proportions but likewise to investigate the logic of its design structure.

The bust of Queen Marie-Antoinette.

In its form wonderfully suited to its precise purpose. Shaped in glass and used as a punchbowl, it was probably not the most suitable form for a vessel. Look it up in Ed Fuchs’s monumental work on the history of manners.13 There you will see the nonsense that Frenchmen produced as recently as the eighteenth century: the photo of the famous punchbowl. Nobody will imitate that now!

But in film we are still playing Marie-Antoinette. Admittedly Marie-Antoinette is sometimes called Dubarry, Lady Hamilton or Tom Mix.14 The names change. The essence remains the same. The focus is exclusively directed towards the actor.

The task of film? Years ago I called it the Luna Park of our emotions.15 Of the emotional conditions into which the audience is pitched. Entertainment film is stuck there. For true film this is just a means to drill the intellectual thesis through the emotions into the audience! And the role of the actor was a means to convey emotion.

The actor was and is the most direct object of imitation. We never know precisely what is going on inside another person.

We see his expression. We mimic it. We empathise. And we draw the conclusion that he must feel the same way as we feel at that moment.

The actor shows us how to feel.

That’s fine. Why then rack your own brains! Everything is all so straightforward.

It is certainly the most straightforward way. But also the most restrictive.

Utilising the individual, he must break down the barriers as soon as it turns into the social-monumental.

The protagonist becomes the mass. Thus mass film arises.

But film cannot stand still either.

The depiction of mass movement is not yet an end. The mass, as dramatic actor, must once again give way.16

A new demand arises: to give pathos to everyday life. After the pathos of the bloody years of struggle comes the pathos of construction. The epoch of reconstruction.

In Potemkin it was simple. Pathos in form was at the same time pathos in treatment. Content and form coincided.

A concrete example of giving pathos to everyday life: the separator in The General Line. And pathos. The principle of construction is derived from the pathos of the situation. Eroticism is far too strong a force not to be utilised. It is ‘delocalised’. Not a love situation but a treatment of the subconscious. The General Line once more.

That is dealt with fully in my book.17

All well and good. But do we need that?

Yes!! Film in its present state is worse than chained. On the technical front it is developing. But it always stays the same. What is conclusively acquired in school and drummed in emotionally is simply used by art: the fear of concentrating a problem. The fear of the new. The fear of a new coherence. Only new forms can elicit new questions. And new questions can only throw up a new social system.

And that is the role of Soviet film in film culture. I do not believe that we are particularly gifted. But the new social situation creates new problems. Anyone who wants to stand at the summit of monumental life in Russia must immerse himself in these problems emotionally. And traditional form will not help him. There must be a new basic principle.

We have to create new forms because we need them. That is the difference between our avant-garde and the other. Objectivity etc.18 The emergence of associations. …Rastelli at the wireless receiver.19

The film of fact.

‘Factual’ play (illusion).

Play with facts (montage of visible events).20 The creation of a new world.

Only now do we see that the fear of the sycophants was well-founded! We must seize the principle of nature and the new technological man will become Almighty in the sense that the Bible attributes to the Almighty.

Berlin, September 1929

Translated from the Russian by Richard Taylor

SOME PERSONAL REFLECTIONS ON TABOO1

Sergei Eisenstein

I like M.

Today I catch myself drawing her from memory. And suddenly I realise why in ancient religions people were not supposed to depict the images of their deities.

Jehovah’s bass voice boomed from the cloud-covered heights of Sinai, ‘Thou shall not make to thyself any graven image, nor the likeness of any thing’.

In Persian miniatures and other examples of religious painting the central deity has a blank spot instead of a face.

The name of God was taboo to primitive peoples.

It could not be spoken aloud. This reflected the limitations of the mode of thought of primitive man. Name and being were the same thing—identical. To name a name was to summon up the being. To name Him was to draw Him to oneself.

So what…?

I think that it is possible to go further.

Let me say something about depictions from my own experience of life.

I liked a girl called K. Getting to know her was a very slow and difficult process. Surprisingly I draw quite quickly. In the drawing I achieve a reflex immediacy which translates the idea/conception straight into the drawing. That is how Alexander Ostrovsky taught the actor’s craft, using the very same term ‘reflex’!

In pursuit of immediacy I am trying to think in strokes. For that reason I have stopped using a rubber or making an outline sketch.

For a long time I have been trying to capture K. on paper from memory. Just as unsuccessfully as on the other side of the paper. At last, I have managed it. And I captured the character of her appearance at the moment when…well, you know when. But it was by no means because of this. No! It was simply that both lines of depiction, developing uniformly, reached their conclusion at the same moment. The model submitted both on paper and in the psychology of consent.

I remember that it was the same on at least three other occasions (L., V. and E.). The moment the image was captured on paper, the subject submitted psychologically.

This seems almost like magic operating. What is more, beforehand, before there was a lifelike depiction on paper, I had no success whatsoever!

What curious devilment!

But I think that the drawing here repeats the gradual pace of capturing the features of the model herself. We come to resemble those we love. Do we not sometimes catch ourselves reproducing the person we love in our gestures and intonations, our movements and manner of thinking?

Isn’t this why the English language, in order to distinguish the first stage of love, i.e. the stage preceding fusion (love), has preserved the term ‘like’, which simultaneously conveys the sense of ‘I like’ (something less than ‘I love’) and ‘I resemble’?!

Isn’t this glaringly obvious from women in love?

Don’t they think our thoughts, speak our turns of speech, use our words?

Wasn’t I right to make Anastasia in my Ivan the Terrible speak about the state and power with the words originally used by Ivan? The objectivisation of the features of the loved one in oneself is a characteristic of women.

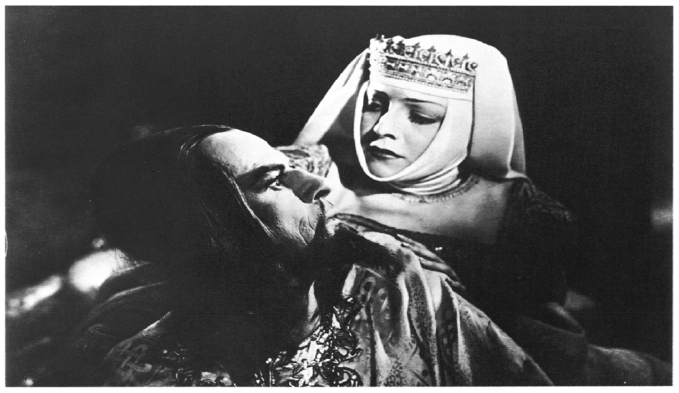

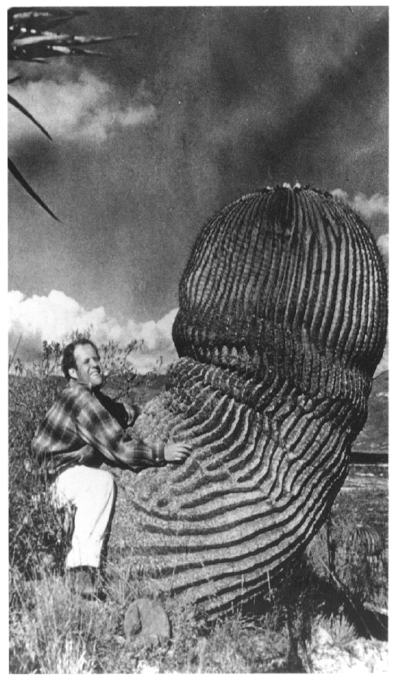

Figure 16 Photograph sent by Eisenstein to Ivor Montagu from Mexico in 1931: ‘Makes people jealous!’

Men apparently externalise. On to raw material. On to their surroundings. On to the heroine of a novel. A woman’s image on the screen. Drama. Elegy. And…drawing.

But complete objectivisation is possible only in the case of complete (psychological) identification with the image of the model. This is the moment of simultaneous perception of her within oneself. This is the fusion. From this derives complete knowledge.

We do however remember what it means to ‘know’ one’s wife in the biblical sense. It does not just mean to fuse with her. But, from the position of an admirer—to possess her.

You can only imagine another person at the second stage. After the first stage in which at first you mimic the model. You reproduce her subjectively in yourself in order to return her once again to objectivity, as an image on paper.

It is only when this process of mutual penetration—getting inside the model and accepting her within you—is achieved that the image will come on paper.

For the image is precisely the combination of features that, when we perceive it, forces us to recreate the original. It is not, however, a depiction which reflects in a dead and precise way existing detail.

Thus the image on paper is a reliable indicator of the fact that this mutual penetration, with its accent on the man as the active originator, has already happened.

The drawing is not a magic key to fulfilment, but an indicator of the degree of ‘crystallisation’ of the relationships.

‘Relationships’ because this is possible from one side. The degree of penetration is furthermore an indicator of the defensive position of the besieged citadel, the degree to which and to what extent the attacking forces have been admitted into it.

That is probably why we are not allowed to depict the image of God.

To depict Him means to amalgamate with Him.

To possess Him.

To stand in His place….

22 January 1943

Translated from the Russian by Richard Taylor