Chapter 6

Eisenstein’s theatre work

Robert Leach

There are generally agreed to be three main streams in twentieth-century theatre: Realism-Naturalism, usually associated with Stanislavsky; Surrealism and the ‘theatre of the absurd’, whose best-known practitioner was probably Artaud; and finally, ‘public’, political, social, epic theatre, generally linked with Brecht. The roots of this third, Brechtian theatrical form are usually sought in the theatre of German Expressionism, the work of Büchner and Wedekind, the fairgrounds and cabarets Brecht frequented as a youth, even (as a reaction) Wagner’s grandiose theories. But actually the specific form was first and in some ways most clearly utilised in the theatre of the Russian Revolution by those who wished to create an ‘October in the theatre’. Meyerhold should perhaps be regarded as the real founder of it, yet Eisenstein is probably the practitioner who most clearly crystallised it.

The form was developed simultaneously on three fronts: playwrighting, play production, and acting. And, although Eisenstein himself was primarily concerned with play production, each of the three is considered at various points in this chapter.

Eisenstein’s major theatre work was all carried out under the auspices of the Proletkult, where he and Boris Arvatov determined to create an ‘agitational-dynamic’ theatre. For both of them, their first opportunity was the proposal to stage The Mexican, a story by Jack London. They approached the project with the mixture of diffidence and bravado which characterised the approach by Rivera, London’s hero, to Kelly, the boxing promoter. Arvatov made a rough dramatisation of the story, and Eisenstein was appointed designer, jointly with Nikitin. The production was ostensibly by Valentin Smyshlyayev, but it was to be a collaborative work, an improvisation from Arvatov’s script, which meant that others in the group contributed heavily to the finished creation.

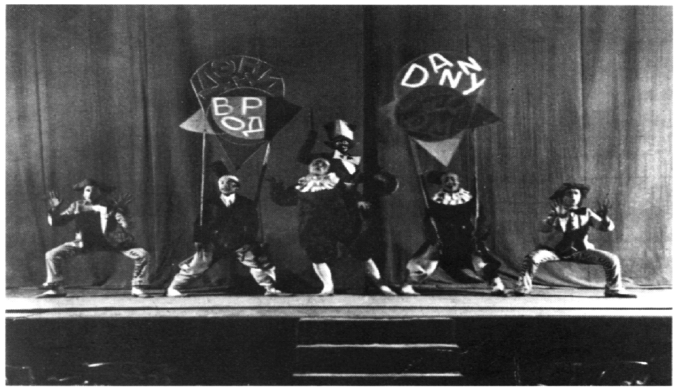

None contributed more than the exuberant co-designer, Sergei Eisenstein. He devised a Cubistic set, consisting of cones and triangles, squares and cubes, and dressed most of the characters in fantastic, clownlike costumes which echoed the stage decorations. The exception was Rivera, who had no make-up and wore a sombre cloak and hat. The acting style, which was arrived at democratically by the whole group, was grotesque and acrobatic, capitalising on the ‘eccentrism’ then fashionable, but perhaps more vividly and imaginatively employed than usual. It was a style which rejected ‘psychologism’ and was rooted in popular, lower-class entertainment.

But Eisenstein’s most notable suggestion ran clean contrary to this style: it was to stage the climactic boxing match as a ‘real event’:

We dared the concreteness of factual events. The fight was to be carefully planned in advance but was to be utterly realistic. The playing of our young worker-actors in the fight scene differed radically from their acting elsewhere in the production…. While the other scenes influenced the audience through intonation, gestures and mimicry, [this] scene employed realistic, even textural means—real fighting, bodies crashing to the ring floor, panting, the shine of sweat on torsos, and finally the unforgettable smacking of gloves against taut skin and strained muscles.1

In Eisenstein’s phrase, this was ‘real doing’, and it was set beside the ‘pictorial imagination’ of the other scenes. These two strands—utilitarian and expressive—were the sharply contrasting acting styles through which Eisenstein constructed his future theatrical works.

The Mexican was sensationally successful but, for reasons too complicated to go into here, the group responsible for it did not produce another show for well over eighteen months. By then, Eisenstein had taken over as artistic director, having spent some months working at the extreme avant-garde theatre workshop of Nikolai Foregger and a year as a student at Meyerhold’s Higher Institute of Directing (GVYRM), during which time he had assisted the Master (as Meyerhold was known to his students) in one of his most daring productions, The Death of Tarelkin. He had also seen Nemirovich-Danchenko’s extremely predictable production of Ostrovsky’s comedy, Enough Simplicity for Every Wise Man at the Moscow Art Theatre, and had presumably heard Lunacharsky’s call for the Soviet theatre to get ‘back to Ostrovsky’ in 1923, putting away the more outrageous forms of ‘eccentrism’ (of which the production of The Death of Tarelkln was a notorious example) in favour of a more considered realism.

Eisenstein’s response was his most famous stage production, a free adaptation by the poet Sergei Tretyakov of Enough Simplicity for Every Wise Man, out of which came, directly and immediately, his theory of ‘the montage of attractions’.2 Retitled simply Mudrets (Wise Man) it was probably the single most shocking, brilliant and challenging production in the Soviet Union during its post-Revolution ‘golden age’. It was followed by two more productions of plays by Tretyakov—first, the ‘agitguignol’, Can You Hear Me, Moscow?, and then the melodrama, Gas Masks, staged in an actual gasworks—before the group went on to make the film, The Strike, and never returned to the theatre, at least not as a group.3

Because of this migration to another medium, their contribution, and especially Eisenstein’s, to the development of epic theatre seems to have been largely overlooked. Yet the method evolved for constructing a play, which is clearly visible even in parts of The Mexican, was highly original, and, I suspect, much more influential than has until now been acknowledged. It is a method which involves making a play as a ‘montage of attractions’, that is, creating a series of apparently self-contained scenes or episodes, each utterly different from the others, whose true meaning is only apparent when they are laid side by side and allowed to interact with the other scenes or episodes juxtaposed to them. Each scene is an ‘attraction’, that is, an ‘aggressive moment in theatre’,4 which grips the audience in one way or another, and creates its own immediate response —suspense, titillation, laughter and so on—through the presentation of its content— symbolic, satirical, political or whatever. The greater the variety of kinds of scene, the better. In the terms of the early Russian Formalists, who were the avant-garde’s close critical allies at the time, the method employs highly artificial ‘devices’ as its basic mode of operation, in order to ‘make strange’ its ‘material’.

Following from this, it is the ‘basic material’, in Eisenstein’s terms, which ‘moulds’ the audience ‘in the desired direction (or mood)’.5 This in turn demands a new approach to acting, and Eisenstein worked hard to develop a suitable training programme for the stage actor, one which could perhaps be revived, at least partially, with some profit:

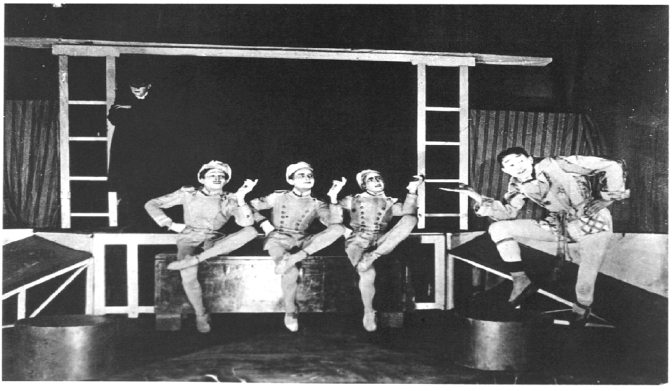

In the first place, it is a physical training, embracing sport, boxing, light athletics, collective games, fencing and bio-mechanics. Next it includes special voice training, and beyond this there is education in the history of the class struggle. Training is carried on from ten in the morning till nine at night. The head of the training workshop is Eisenstein.6

The programme may have owed a considerable debt to Meyerhold’s Workshop, where Eisenstein had been studying, but it includes several original features and is clearly aimed at developing the actor’s ability to ‘jump’ from utilitarian to expressive acting styles and back again at a moment’s notice. The purpose of the jumps is to keep the audience on its toes, remind it that it is in a theatre, not lost in dreamland and direct its attention towards the theme and away from an all-absorbing psychology or fate. ‘Down with the story and the plot!’ Eisenstein wrote in 1924.7 This method of acting was one of the tools he forged with which to do them down.

It is a method which enables the actor to cope, for instance, with the overt theatricality of Eisenstein’s productions. This is initially seen in his finales. The climax of Can You Hear Me, Moscow?, for instance, is a play within a play (or rather, a pageant within it), while that of Wise Man is a film (Glumov’s Diary). In The Mexican, it is a boxing match, a ritualised, or theatricalised, transposition of a fight, staged with what spectators found to be alarming, though compelling, realism. By thus drawing attention to the theatricality of the event at the moment of its climax, Eisenstein deliberately exploits the contradictions between reality and artificiality, thereby hindering the spectator’s incipient desire to ‘identify’ with the fictional characters and replacing it with a means of establishing a new relationship with the world, and society, beyond the theatre.

This, of course, explains Eisenstein’s own appearance at the end of the film of Glumov’s diary, as it explains why in The Mexican the auditorium is extended right round the boxing ring, with actors playing the part of spectators opposite the real spectators. This is more than ‘audience involvement’, it is a disruption of the audience’s normal role in the theatre. It is presaged in The Mexican, for instance, by the way the actors directly address the audience between scenes, sometimes ‘in character’, sometimes directly as themselves. In Wise Man, fireworks exploded under the spectators’ seats at the end of the play, in Can You Hear Me, Moscow?, the cast turned to the audience to demand: ‘Are you listening?’ and they were supposed to respond: ‘I’m listening!’ The climax of this relationship was reached in Gas Masks which began with a character ‘purifying’ the air of the gasworks with a spray, and ended with the real night shift workers coming on duty. Obviously this is a deliberate subversion of the illusion. Its purpose is to focus the audience’s attention elsewhere: on the public and social issues beyond the world of the drama.

The attractions imported from the circus served the same ends, by forcing the spectator to admire the performer as performer. Alexandrov’s famous walk on the tightrope above the heads of the audience in Wise Man symbolised the dangers of returning to Bolshevik Russia for a White émigré, but it was exciting because of the inherent danger that the performer would fall off the tightrope. This is a specifically theatrical attraction because the danger is live, here and now. The same is true of the other acrobatic or gymnastic ‘attractions’, like the entry of the Komsomol youths in Gas Masks, vaulting over the workbenches, not to mention the extensive clowning.

Clowns like George and his mother in Wise Man (the mother being the red-wigged buffoon of the circus) are attractions in themselves, but often the techniques of clowning were adapted by Eisenstein to form other attractions. In The Mexican, for instance, there was an episode involving the fight audience when an alluring dancer began making eyes at a priest, who was watching in company with his wife. He began to respond, thereby attracting his wife’s attention, whereupon she flew at the dancer and began beating her about the head with her umbrella. The husband rushed after, and dragged his infuriated spouse away to the loud guffaws of the gleeful stage spectators: a perfect example of an attraction, a self-contained unit, with characters who never reappear, in an action which adds nothing to the ‘story’ but, placed as it is between rounds of the boxing match, makes its own implicit comment on that fight. This little episode was itself implicitly commented on in the next pause between rounds when a Japanese docker offended a dignified elderly lady by his support for the unfancied outsider, and was attacked by her.

In Can You Hear Me, Moscow?, Marga, the Count’s mistress, provides a more explicitly venal kind of attraction. Tie my boot-laces,’ she suddenly cries when not enough attention is being paid to her:

Everybody throws themselves at her feet; the Count, wheezing, at last gets down on his knees with difficulty.

VOICES: What legs! Like marble! She’s a goddess!

POUND: In a New York music hall she could make a fortune.

MARGA (squealing and laughing): Don’t tickle! Whose are those whiskers? Count, stand up!…etc.8

Actually, Eisenstein directed the episode so that while the Count was doing up the laces on Marga’s high boot, she placed her other boot on his neck in the pose of a big game hunter with a ‘trophy’. It is the unexpectedness of the episode, and also perhaps its irrelevance in plot terms—in Meyerhold’s phrase, its ‘retarding’ quality—which makes it so striking.

Another of Eisenstein’s favourite devices for the creation of attractions is parody, often of a highly unexpected kind: the film of Glumov’s diary parodies contemporary thrillers, for example, while Glumov’s desire to hang himself a little later leads him to ascend on a rope to the ceiling in a parody of the Ascension. The entry of the aristocrats in the final scene of Can You Hear Me, Moscow? takes parody into political satire, while the entry of the aunt in Wise Man satirises bourgeois pretensions and parodies the circus to make its own distinctive attraction: the three suitors whom Mamayeva wishes to console turn (at a mention in the dialogue of ‘a horse’) into a horse and rider, and Mamayeva cracks her whip to make it prance as if in a ring.

Still other attractions provide the political message: out of a chaos of darkness, screaming and confusion after the boxing match in The Mexican, spotlights pick out the triumphant figure of Revolution, arising out of the mêlée. In Gas Masks, the anti-religious message is dramatised in a clown ‘turn’, when Vaska enters with an icon, pursued by a group of Valkyrie-like icon-wielding women, who set about him with their holy placards! In a few moments, the icons are smashed to firewood. The New Economic Policy is similarly mocked in Wise Man in a comic fight between Glumov and Golutvin, which ends with Glumov pulling a sign reading NEP out of Golutvin’s pocket, which prompts a quick song-and-dance routine from the pair. The class war is caricatured rather more bitterly in Can You Hear Me, Moscow? in the scene where Marga meets Kurt. ‘Look at this dishy specimen’, she says. ‘What a chest, what a pair of eyes.’ He disdains her, but she persists, inviting him to kiss her leg. ‘Why not? They say my legs are very beautiful. Don’t they tickle your fancy?’9 She lifts her skirt higher. Kurt spits at her. She flies into a rage, attacking him and striking him with her whip until she is dragged away.

The show develops through such symbolic and melodramatic attractions. Other examples include the unmasking and murder of Stumm, the informer; 10 the pulling down of the builders’ scaffolding at the end of Act Two; the unveiling of the massive portrait of Lenin in Act Three; and the apparently fortuitous placing of a hammer across a sickle in the play within the play. Here, typically, part of the success of the action resides in the fact that it interrupts another action: the pompous poetic commentary on the pageant concerns the Christianisation of the ‘savages’:

MARGA: What delightful poetry!

BISHOP: Very instructive.

(In the crowd of savages ready for the struggle, as if accidentally, the hammer and the sickle are crossed, one over the other.)

VOICES: The hammer and sickle! Look, the hammer and sickle!

It’s November the Seventh!

Remember Moscow!11

The interruption reveals the Marxist kernel of the situation: that in the oppression of the ‘savages’ there is the potential for revolution. This is precisely what is meant by each attraction containing its own ‘point’.

But rarely are matters as simple as that. Much more usually, it is the relationship between the attractions, however varied they may be, that contains the meaning; that is, the meaning is in the montage, which then demands what Brecht was to call ‘complex seeing’: the different attractions set up a series of reverberations which are constantly modified in unexpected ways. In the interlude between Acts One and Two of The Mexican, Eisenstein devised a sequence of attractions which illustrate this clearly. Fairy lights light up the proscenium arch, the revolutionary leaders come forward and begin haranguing the audience about the evils of capitalism, especially as it manifests itself in Mexico. Destroying the stage illusion, they appeal to the spectators not to forget the plight of the real Mexico in their excitement about constructing socialism in the RSFSR. The speech ends with a policeman arresting the speaker as an agitator, bringing the spectator back into the fiction. Two clowns rush out, and knock down the policeman. The revolutionary escapes hastily through the auditorium, with the policeman in hot pursuit. The clowns remain. They now begin a crosstalk act with pointed references to contemporary features of life in the young Soviet state. They are interrupted by the appearance of two young women hanging on the arms of the impresario of the boxing match. The clowns watch amazed as they charm free tickets for the match from him and then con a lascivious passer-by into buying them at a hugely inflated price. The policeman returns, and his suspicions are alerted by the young women’s heavy come-hithers. Is that a whiff of speculation he smells? Somehow, the clowns get involved again, the buyer of the tickets is dragged away, there is a noisy and acrobatically stunning chase on stage and in the auditorium, in the middle of which the director (or an actor playing the director!) appears and shouts at them to get to their places, the second act is beginning. They rush away, the house lights go down and the next act commences.

It is breathless, fast, funny and above all full of variety and surprises. There is a political speech, which works both within and outside the context of the play, an arrest, a chase, clowns making satirical comments, a cheeky piece of swindling, the use of sex to get one’s own way, a theatrical chase and a highly unorthodox interruption to end the sequence. There is no precise ‘meaning’; rather, the devices employed prod the audience into sitting up, rubbing their eyes and looking again, and perhaps, hopefully, into making connections between the various kinds of action presented. In The Mexican, the montage is a bit of a jumble, though what Eisenstein is aiming for is clear enough. In Wise Man, it was less a jumble than a riot. The method was considerably disciplined and tightened in Can You Hear Me, Moscow?, in which a much less overtly eccentric drama was presented in such a way as to focus on the political themes, at the expense of traditional characterisation and psychology. And in Gas Masks, the method was theatrically more or less consolidated.

By the time of Gas Masks, the theatre was, from Eisenstein’s point of view, a limitation—hence his wish to present a play in a factory—largely because the method as he had developed it now required a greater potential for ‘collisions’ between the attractions. This the theatre could not provide, for after any striking moment the actors had to move on and reassemble for the next striking moment. Film provided much greater scope, for instance, to cut from a frowning face, to a cream separator, to a smiling face. Theatre cannot do this, but must work to a different rhythm.

Nevertheless, Eisenstein’s achievement was extraordinary. He had developed a series of interlocking components which together comprised not so much a style as a new dramatic form—epic theatre (which, by the way, Aristotle had said was a contradiction in terms). It was an ‘action construction’ in the sense that meaning was in the action, not in reflections on the action (the boxing match, not the reactions to the boxing match). Its method was grotesque, that is, it allowed utterly dissimilar events, or styles or emotions, to occur in quick and apparently random succession, with absolutely no heed to dramatic unity or decorum. It proceeded by means of attractions, individual episodes, complete in themselves, which caught the spectator’s attention and contained their own point. They were bound together by the montage, which provides the apparently disparate elements with a new kind of unity, one which relates to the world beyond the play. To revert to the terminology of the Formalists, montage ‘makes strange’ reality and organises the work’s material in new and surprising ways so as to capture the spectator’s imagination.

This was the first consciously defined form of epic theatre, a form more usually associated with Brecht. Thus, where Eisenstein talks of ‘attractions’ to describe moments like Marga’s attack on Kurt, Brecht speaks of ‘gestus’ when referring, for example, to moments like Garga’s attack on Shlink; Eisenstein’s ‘montage’ bears a striking similarity to Brecht’s ‘interruptions’; and while the Formalists talk of ‘making strange’, Brecht uses the term ‘Verfremdungseffekt’ or ‘alienation’. The key concepts are virtually the same, but Brecht almost certainly got them from the Russians, ultimately from Eisenstein. This is not to imply any sort of simplistic handing over of a series of pre-packed instructions for the making of a play, nor is it to deny or belittle Brecht’s own huge contribution to the creation and development of twentieth-century epic theatre. But the process needs to be located in the network of writers and theatre practitioners who were responsible for the working out of these creative methods and ideas, and the flow is generally from the Russians to the Germans, or more specifically, from Eisenstein to Brecht.

One central figure in this flow is Sergei Tretyakov, who did not go with Eisenstein into films, though after his stage career was blocked by the censors he did compose a number of screenplays: in 1928 he scripted Eliso for Nikolai Shengelaya, which was, according to Jay Leyda, ‘a triumph’; in 1930 he worked out the scenario for Salt for Svanetia for Mikhail Kalatozov which Leyda calls a ‘masterpiece’ and ‘the most powerful documentary film I’ve ever seen’;12 and in 1931 he wrote the screenplay for Song About Heroes, directed by Joris Ivens and with music by Hanns Eisler, about building the new industrial complex of Magnitogorsk. All that was after he had written other stage plays, most famously Roar, China! for the Meyerhold State Theatre, widely seen and acclaimed when the company took it abroad in their repertoire on tour in 1930; and I Want a Baby, which was instantly banned and, despite rewrites, has, to the best of my knowledge, never been staged. Yet it is a superb play, built up through a montage of disparate scenes, and almost the only leftist epic drama which deals specifically with the problems of human sexuality. It is perhaps significant that Brecht spent some time trying to make a German version of it. The banning of I Want a Baby, Tretyakov’s dramatic masterpiece, seems to have turned him away from original play creation. Apart from his documentary film scripts, his only other dramatic work seems to have consisted of translations into Russian of several plays by Brecht, versions the author highly approved of, and insisted were used even in the frozen post-war Stalinist era when Tretyakov’s name was utterly unmentionable. He was shot as an ‘enemy of the people’ in 1939.

Tretyakov’s most interesting contribution to the development of the theory of theatrical montage came in the areas of playwrighting and stage speech. In 1923, after his experience with Wise Man, he wrote Earth Rampant, an adaptation of Night by the French Communist and pacifist, Marcel Martinet. In place of the lyrically decorative original, Tretyakov created a script which was sharply episodic, an ‘action construction’ which turned on the incidents of the story: in other words, where Martinet’s play focused on the reactions to the events, Tretyakov’s focuses on the events themselves. The individual episodes are ‘marked by cinema-like captions with the aim of creating agit-collisions’, Tretyakov commented, slogans and comments were projected on to screens. ‘The largely figurative poetic phraseology was simplified’, he added, and ‘the re-formed action complied with the principles of montage.’13

The programme for this production at the Meyerhold Theatre stated that the ‘montage of the action’ was by Meyerhold, the ‘montage of the text’ by Tretyakov. In effect, this meant that Tretyakov had worked with the actors on the problems of speaking the text. He himself defined the problem as being ‘to teach the actor-worker not to converse and not to declaim, but to speak’. This he attempted to do by shifting the emphasis away from the melodic elements in speech, the vowels, on to the ‘articulatoryonomatopoeic (the consonants)’, and away from ‘conversational intonation (usually unreal anyway, since real conversation accumulates verbal rubbish as well as all sorts of drawings in of breath, hiccoughs, clearings of the throat and other messy noises)’ on to ‘rhythmical configurations’ which were ‘crystallised from examples of common phraseology’. Speech then took on the quality of ‘verbal gesture’ and the actor’s task was to create a ‘vocal mask’ analogous to his ‘set role’.14 Once the actor has acquired this, he is equipped to ‘jump’ from expressive to utilitarian modes without strain. Thus, Tretyakov attempted to extend Eisenstein’s theory of montage to text and speech, in effect to find a new way of writing plays and a new technique of acting.15

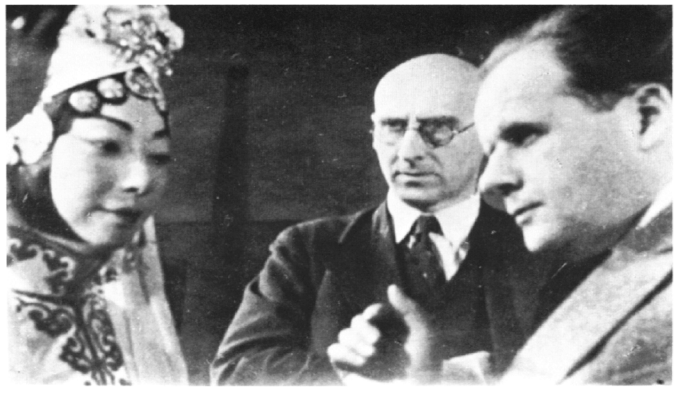

Tretyakov first met Brecht in Germany in 1930. In 1931 he returned to Germany to lecture on ‘The Writer and the Socialist Village’ and spent some time during his five months in the country with Brecht, who took him to Augsburg, his birthplace. Tretyakov’s view of Man Equals Man in Brecht’s 1931 production which he saw during his stay was that only Meyerhold’s version of The Magnanimous Cuckold had made a deeper impression on him.16 Brecht and he became friends and allies (‘my teacher, tall and kindly’, Brecht called him17) and equally targets for Lukács’s polemics against unorthodoxy. Tretyakov published Brecht’s Epic Dramas in Moscow in 1934, the same year that Brecht was telling an interviewer for the Swedish newspaper, Ekstrabladet, that ‘in Russia there’s one man who’s working along the right lines, Tretyakov; a play like Roar, China shows him to have found quite new means of expression’.18 The next year, Brecht stayed with Tretyakov in Moscow, where he was introduced to Viktor Shklovsky, the Formalist critic and film scenarist. ‘Ostranenie’ was Shklovsky’s term: it translates as ‘Verfremdungseffekt’ or what has come to be known in English as the ‘alienation effect’. As secretary of the international section of the Writers Union and committee member of the Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries, Tretyakov was instrumental in arranging the performance programme of the visiting Chinese actor, Mei Lan-fan, at this time, and it was in his article written about Mei Lan-fan after watching him in Moscow, that Brecht first used Shklovsky’s term and discussed the ‘Verfremdungseffekt’: the essay is reproduced in Willett’s Brecht on Theatre as ‘Alienation Effects in Chinese Acting’.19

But, if Tretyakov is the closest and most obvious link between Eisenstein and Brecht, he is by no means the only one. For political-historical reasons, Germany and the Soviet Union were ostracised by the international community in the 1920s, and therefore took much notice of each other culturally. One couple involved in the traffic between the two countries were Bernhard Reich and Asja Lacis. Lacis studied acting with Kommissarzhevsky in Moscow, and then in 1920 at the State Film School, where she was when she appeared in Kuleshov’s On the Red Front.

In 1922 she and Reich moved to Berlin, and in the following year Reich became director of the Munich Kammerspiele, where Brecht was due to mount Edward II. When Brecht met him and Asja Lacis he ‘interrogated her. He was visibly interested in information about Soviet Russia and its cultural politics. This conversation was followed by many others.’20 The ‘cultural polities’, of course, concerned Eisenstein and his relationship with the Proletkult, the development of Meyerhold’s theatre and the progress of the infant Soviet film industry, particularly as it concerned Kuleshov, Eisenstein and others. Lacis became Brecht’s assistant director on Edward II, and even played the part of the king’s son. Not surprisingly in the light of Brecht and Lacis’s ‘many’ conversations, ‘the production contained the seeds of a new way of writing plays, and…a new technique of acting was revealed’.21 These were based in the kind of theatre which Lacis had learned from the avant-garde in Moscow. Volker comments that this production ‘became, as it were, the foundation stone of the Brechtian theatre’.22 Reich explains at least part of the apparent originality:

German actors attach little importance to formal actions such as eating, drinking or fencing. They summarise them, simply indicate them casually. Brecht, however, demanded not only that they should be performed realistically and exactly, but that they should be skilful. He explained to the actors that such actions on the stage should give the audience pleasure.23

The technique, of course, is precisely that developed by Eisenstein for the boxing match in The Mexican, where he insisted that the fight be performed absolutely believably. This was in 1921, while Reich and Lacis were still in Moscow, and closely in touch with the circles Eisenstein and his company moved in.

In 1924, shortly after the Edward II production, Asja Lacis met the critic Walter Benjamin, who found her (as Brecht did) extremely attractive. She and Reich returned to Moscow in 1925, and Benjamin followed them there in 1926. On New Year’s Eve, he met Meyerhold, having already been excited by his work, and was present at one famous ‘dispute’ about Meyerhold’s production of The Government Inspector:

Thousands collected in the huge hall to discuss Meyerhold’s staging of [the play]. They followed the controversy with every fibre, interrupting, applauding, shouting, whistling. The Russian speakers fascinated Benjamin: he thought they were born tribunes. Among others, Mayakovsky, Meyerhold and Bely spoke.24

By 1928 Lacis was back in Berlin with the Soviet Trade Delegation responsible for film distribution. The following year she introduced Benjamin to Brecht, and a highly important connection was made: all Benjamin’s shrewd comments on Brecht’s theatre are informed by his ‘fascination’ with the Russian avant-garde theatre.

The list of mutual contacts between Eisenstein and Brecht could be prolonged considerably. There was, for instance, the musician Edmund Meisel, who composed the score for The Battleship Potemkin when it came to Berlin in 1926. He worked in the closest possible collaboration with Eisenstein to produce ‘a new quality of sound structure…a unity of fused musical and visual images’.25 At the same time Meisel was working almost equally closely with Brecht on Man Equals Man: Brecht ‘sketched rough drafts of the songs that Edmund Meisel…actually composed’.26 It was immediately after this that Brecht did his most potent work with music, in dramas such as The Threepenny Opera. Meisel went on to work extensively with Erwin Piscator, whose connections with the Moscow theatrical and cinema worlds are also well known. The chronicle could continue, but perhaps the point has been made.

Eisenstein met Brecht in Germany in 1929, and on the train to Moscow in 1932, when Eisenstein was, according to Brecht, ‘ill’.27 Both were also present at the same performance by Mei Lan-fan in Moscow in 1935. But by then, Eisenstein had left his theatre work far behind and Brecht was not in need of his personal support. Brecht certainly admired The Battleship Potemkin as much as anyone, and intended to invite Eisenstein to join his projected ‘Diderot Society’ in the later 1930s. But he never admitted to being influenced by Eisenstein in the development of his own concept of epic theatre, perhaps because he was unsure of just how great that debt might be. For Eisenstein’s theatre work, which aimed to ‘mould’ the audience through a montage of attractions, should be seen as probably the earliest conscious demonstration of epic theatre in practice and his formulation as perhaps its first exposition.