Chapter 9

Graphic flourish

Aspects of the art of mise-en-scène1

Arun Khopkar

Carpenters and Brahmins must evolve a common language.

Ritwik Ghatak2

THE FRAME

Eisenstein’s unfinished work Rezhissura (Direction) occupies a unique place in his writings. Instead of an a posteriori analysis of his own work or that of other artists, this book offers something different. It is concerned with the minutest practical details and problems of mise-en-scène—the turning of the head, the raising of a hand, the size and shape of a window. But at the same time Sergei Mikhailovich is searching for solutions and means of solution—in different art-forms and sciences, in the diaries and letters of artists and scientists, and in his own experience. The breaks in the narrative (the line of solution) provide pleasure and increase our excitement. They give this book something of the form of a detective novel, a form which Eisenstein very much loved. But this whodunit has no simple, unique solution, since the deed is not done. We merely review different ways of doing it. It combines, so to speak, the crime with the psychology of crime, action with reflection. It is as if the imagination had left a fluorescent trail as it flitted from flower to flower.

And yet it remains the least-known of his writings. Montage and Non-Indifferent Nature and his writings on colour have been fully or partially translated into French, Italian, German and, finally, English. Given the split between film theory and practice today, this is scarcely surprising, but neither is it desirable.

What follows is not a summary of Rezhissura. It is an attempt to trace the various strands that form the concept of mise-en-scène. It is an establishing shot.

THE FROZEN AND TREMBLING CONTOUR OF MISE-EN-SCÈNE

In their notes to the English translation of Nizhny’s Lessons with Eisenstein, the editors define mise-en-scène thus:

By this expression Eisenstein simply means what it means in the theatre, that is the arrangement of the actors on the stage…it has the limited meaning of: the determination of the details of action for stage purposes, including, primarily, the positioning of the actors at different places (or for different ‘sections’ of the action), their movement in the space determined by the set, the determination of the set to accommodate the action.3

Unfortunately, although this definition of mise-en-scène has the advantage of simplicity, it leaves out some of the most vital elements. It ignores the subjectivity of the director. The rest of Nizhny’s otherwise useful book also gives us the impression that to every problem of mise-en-scène there is an ideal, absolute solution. The universe of a work of art, in particular a film, begins to resemble a Newtonian system where the space-time continuum is absolute. The ‘logic’ and ‘laws’ of composition seem to decide all the formal problems with an impersonal thoroughness. Even Ley da is uncomfortable about the tone of the book.4

Eisenstein’s own definition of mise-en-scène is very open:

What—posing the question in a concise way—is mise-en-scène? Mis-een-scène (in all stages of its development: gesture, mimicry, intonation) is the graphic projection of the character of an event. In its parts, as much as in their combination, it is a graphic flourish in space. It is like handwriting on paper, or the impression made by feet on a sandy path. It is so in all its plenitude and incompleteness…. Character appears through actions (in many cases these are determining aspects). Specific appearance of action is movement (here we include in ‘action’ words, voice etc). The path of movement is mise-en-scène.5

This definition contains all that the former covered, and much more. Mise-en-scène is supposed to project graphically the character of the event. This means that it should reveal something which is not on the surface. It involves turning an in-tension into an ex-tension.

The graphic flourish in space is like the mark of the director/painter. It involves much more than mere skill in the arrangement of the actors’ movements and the determination of the set to accommodate the action. It reveals the director’s personality and in particular his attitude towards the event.

The image of handwriting or footprints is carefully chosen. Sergei Mikhailovich’s interest in handwriting analysis is attested by that portion of his library preserved in the museum on Smolenskaya. Also, his adaptation with Tretyakov of the ideas of Rudolph Bode about expressive movement bears witness to this, as does his study of Ludwig Klages’s work, to which I shall return later.

Eisenstein’s writings on mise-en-scène indicate that it emerges as a synthesis of two tendencies: the graphic and the expressive. These are not mutually exclusive and in fact their fusion and interpenetration is the hallmark of great mise-en-scène. Their separation here is only for the purpose of analysis. I am taking the graphic as relating to geometry, number and proportion; and the expressive as relating to the organic. It is through their mutual tension that the contour of mise-en-scène comes alive.

LOCATING THE POLES: RITUALISTIC AND EXPRESSIVE

Mise-en-scène, as defined above, has to be located within a spectrum. At one (visible) end of this spectrum is ritual (the ultraviolet would be mathematics), while at the other lies the expressivity of our emotional lives (the infra-red would be the warm region of our unconscious and body-rhythms). Between these two poles, we have the entire range of the spectacular: festivals, theatre, puppets, mime, dance, circus, pre-theatre and the like. Mise-en-scène spans this entire range.

Ritual stands as the most consciously controlled event, with a predetermined form and purpose: even if it includes an unknown or chance element, the parameters of its operation are well-defined. So while there may be many variables—place (outdoor/indoor, dimension, natural/ cultural setting), time (relationship with diurnal and annual cycles of the earth’s time, the configuration of stars, weather, etc.), duration, participants, roles to be played, etc.—and each ritual will have its own code, one unified approach to the graphics of mise-en-scène may reveal common forms and structures underlying the specific codes. These would help us to generalise and abstract in our formulation of mise-en-scène.

The other line to be pursued is expressive movement. In Eisenstein this is not confined to the human world, but carries over into the animal kingdom and even the plant world. The dual nature of our investigations is not surprising. As Eisenstein noted:

The dialectic of works of art is built upon a most curious ‘dual unity’. The affectivity of a work of art is built upon the fact that there takes place within it a dual process: an impetuous, progressive rise along the lines of the highest explicit steps of consciousness and a simultaneous penetration by means of the structure of the form into layers of profoundest sensual thinking. The polar separation of these two lines of flow creates that remarkable tension of unity of form and content which is characteristic of true art-works. Without this there are no true art-works….

By allowing one or the other element to predominate, the artwork remains unfulfilled. A drive towards the thematic-logical side renders the work dry, logical, didactic. But over-emphasis on the side of sensual thinking, with insufficient account taken of the thematic logical tendency, this is equally fatal for the work: it is condemned to sensual chaos, elemental and raving. Only in the ‘dually united’ interpenetration of these tendencies resides the true tension-laden unity of form and content.6

The purpose of this chapter is to understand Eisenstein’s concept of miseen-scène, which the author feels would enable us to see the interrelationships between our own dance forms, painting, sculpture and theatre and would pave the way to a new synthesis in cinema. But before we apply Eisenstein in our own context, it is necessary to see him in his own. For this purpose, I have chosen to give first a brief account of the concept of mise-en-scène according to Kuleshov, Stanislavsky and Meyerhold. These were not only great contemporaries of Eisenstein, but influences and indeed exemplars of recurrent tendencies in the history of art.

KULESHOV: THE DEMANDS OF THE RECTANGLE AND THE RITUAL OF LABOUR

There is a beautiful description of the early years of Soviet cinema by Eisenstein:

In the early 1920s we all came to Soviet cinema as something not yet existent. We came upon no ready-built city, there were no squares, no streets laid out, not even little crooked lanes and blind alleys, such as we may find in the cinemetropolis of today. We came like bedouins or goldseekers to a place with unimaginably great possibilities, only a small section of which has even now been developed.

We pitched our tents and dragged into camp our experiences in various fields. Private activities, accidental professions, unguessed skills, unsuspected eruditions—all were pooled and went into the building of something that had as yet no written traditions, no exact stylistic requirements nor even formulated demands.7

Recent research on the links between the pre-revolutionary cinema and the young Soviet cinema has shown that this tabula rasa-virgin land-goldrush picture is not to be taken literally. But it certainly captures something of the pioneering spirit of those days.

We find the same spirit reflected in Kuleshov. Reading him today, one finds his naïvety almost touching, but the singlemindedness of his ‘experi-ments’, the freshness of his approach and the tremendous impact he must have had on his colleagues can be felt even now. His path is well-known; and I only recapitulate some of the important points here.

Influenced by the systematising tendencies in many arts which had gathered force in the decade before 1917, Kuleshov wanted to find out what was unique to this new medium of cinema—wherein lay its power to move the viewer. Young Soviet film-makers had noticed what a great impact the American cinema had created: they studied these films and found that they had more camera set-ups and cuts than the Russian or European ones. This led to the proclamation of ‘montage’ as the main source of cinematic effectiveness, or the ‘cinegenic’ quality. The actual content of the individual shots was initially considered secondary to the effect that would be created from their various combinations. This led to the famous ‘Kuleshov experiments’.8

Having succeeded in producing landscapes and persons that did not ‘exist’ and facial expressions that were not genuine, all by combining shots, Kuleshov soon ran into problems.

When we began making our own films, constructed on this principle of montage, we were set upon with cries of: ‘Have pity, you crazy futurists! You show films comprised of the smallest segments. In the eyes of the viewers the result is utter chaos. Segments jump after each other so quickly that it is thoroughly impossible to understand the action.’ We listened to this and began to think what method we could adopt to combine shots so as to avoid these abrupt shifts and flashes.9

But Kuleshov realised that the problem was more than stylistic. What seemed to be a problem of film continuity was actually one of film unity. His solution was essentially Formalist. He felt that the key to filmic (visual) unity lay in the rectilinear shape of the screen, the element which was common to all shots. And this key was the ‘Cartesianisation’ of all visual elements.

The rectangle implied predominance of the rectilinear elements, in particular horizontals, verticals and diagonals. Straight lines were preferred to curves, geometric forms to natural ones and industrial rather than organic objects.

The principle was extended to acting and to mise-en-scène. ‘We examined the movements of limbs as movements along three axes, along three basic directions’—actually the Cartesian co-ordinates.10 The actor’s training would henceforth be to break down his movements into units which would be articulated along the main lines of composition. The gesture must be ‘digitised’, which leads to a preference for certain kinds of gesture. Obviously he finds the movements of the skilled worker most photogenic—so productivity, work and efficiency take mise-en-scène into the geometrism and single-value system of ritual. Acting is finally reduced to a uniquely determined lexicon of gestures.

STANISLAVSKY: THE INVISIBILITY OF MISE-EN-SCÈNE

Stanislavsky occupies a curious place in the history of mise-en-scène. As an exponent of realism, he would seem the antithesis of Kuleshov on the one hand and Meyerhold on the other. He appears to have taken great pains to erase his handwriting from the mise-en-scène, to remove all trace of his presence at the scene of the action, so that it would look like a slice of life, an act of Nature without directorial intervention.

If the overriding design is to be kept invisible, then each part must appear to have the same degree of autonomy. Each actor must appear ‘natural’—and the mise-en-scène will happen. Hence the concentration on the actor. The ‘method’ to be natural must be shared by everyone. Only then will the real hold together and have a design, even if this remains invisible.

But this ‘maître des grands spectacles with the theatrical range of a Michelangelo’ was not to be ‘reduced to fiddling around with little bits of clockwork’:

In these ancient Hebrew and Armenian surroundings, the fanatics of the Moscow Art Theatre Third Studio are present to a man when Stanislavsky gives his lessons.

‘No, authentic emotions! Let your voices resound! Walk theatrically! Suppleness! The eloquent gesture! Dance! Bow! Duel with rapiers! Rhythm! Rhythm! Rhythm! Rhythm!’—the insistent shouts of Stanislavsky resound.11

So the controlling factor, the flourish in space, was also a nourish in time. It is through rhythm that the actors’ movements are mutually coordinated. ‘Really this is the role of rhythm in what an actor creates. Rhythm belongs to the last steps of the line of generalisation of imagicity, which begins the transformation of a gesture into a metaphor.’12 Thus rhythm, the most biological sensation, makes possible the highest level of generalisation. It is what distinguishes the mise-en-scène of the master from that of followers of ‘the method’.

Eisenstein was an outspoken opponent of the Moscow Art Theatre in his youth, but he gave a detailed and considered analysis of Stanislavsky in the later works Direction and Montage. The relationship between the sensememory and the construction of an image to motivate the actor had particular importance for him. In fact he compares Stanislavsky’s method with the spiritual exercises of St Ignatius Loyola. His analysis of Stanislavsky is also important as an estimation of the internal approach to the problems of acting and creation of images in mise-en-scène.

In passing, it is interesting to note that Dnyaneshwar, the great Marathi poet who was a contemporary of Dante and who wrote a commentary on the Bhagwatgeeta, said in his introduction that he would make the suprasensuous sensuous for his readers. He carefully builds his images, choosing images from the five senses, and makes them clash to create an image which paints the beyond.

Eisenstein told his students that, although Stanislavsky and Meyerhold opposed each other theoretically and ideologically, in practice they realised the strong points of each other’s work and absorbed it unconsciously, seeking not a compromise but a synthesis.13 What he himself aimed at was not a synthesis of these two systems but their transcendence.

MEYERHOLD: THE MECHANICS OF ORGANICITY AND EXPRESSIVITY

Eisenstein wrote of Meyerhold:

Of all his principles, only one is productive…. [And] for this thesis I would be grateful to him till the end of my life, although that may not suffice…. The Alpha and Omega of the theoretical baggage of expressive movement, drawn from the exercises of biomechanics, is packed in its first thesis (and in the 16th, which is a direct corollary of the first):

1. The whole of biomechanics is based on the following: even if only the tip of the nose is active, then the whole body acts. If even the most insignificant organ functions, the whole body feels it.

16. Gesture is the result of the whole body working. That’s it. The rest in my studies of expressive movement is MINE.14

Meyerhold realised that the narrowly utilitarian gesture is economical and the expressive gesture is amplified. But it is necessary to find the right means of amplification.

I was lucky to view a short compilation of footage about biomechanics when I was in Moscow. It consisted of Meyerhold making a speech (although the film is silent), two exercises performed by his students and very brief excerpts from his production of Gogol’s The Inspector. These fragments, even when projected at the wrong speed, still had a magic which —as someone fascinated by cats—I can best call ‘feline’. When one figure was in shot, a single muscle moving produced a response throughout the whole body, penetrating into my body. When an ensemble moved, it had the unity of an organism: the result was more than the sum of its parts.

As I watched this film again and again, I understood why Sergei Mikhailovich had such tremendous respect for his unkind spiritual father. Through the imperfect projection, through the flickering shadows thrown on the wall of the cave-like hall, glued to my chair with my back towards the light, I became aware of the forces which moved me, as a flesh and blood spectacle must have moved Meyerhold’s audiences. Forces that had the condensed power of thousands of years of spectacle.

Eisenstein learned a lot from Meyerhold. Take, for example, the movement of refusal. ‘When you want to move in one direction, as a prelude you move (completely or partially) in the opposite direction. In the practice of scenic movement, it is called the movement of refusal.’15

This is not merely a theatrical trick. As an ancient device, popularised by Meyerhold, it contributed to Eisenstein’s understanding of contradiction as a source of expressivity.

Meyerhold also changed the relationship between the spectacle and the spectator as his mise-en-scène surrounded the latter. In fact he took important steps towards what Eisenstein would later call the stereoscopic cinema, meaning the fulfilment of certain tendencies implicit in the history of spectacle. ‘The image penetrates into the screen, carrying the spectator into depths he has never experienced…the image perceived three-dimensionally (it is a most spectacular effect) as if ‘tumbling’ from the screen into the auditorium.’16

EISENSTEIN: IMAGICITY, ORGANICITY AND THE NON-NEWTONIAN UNIVERSE

For Eisenstein the study of expressive movement begins with organisms which are almost immobile, namely plants. Consider the concept of ‘tropism’, defined as an involuntary orientation by an organism or one of its parts which involves turning and is accomplished by active movement that constitutes a positive or negative response to a source of stimulation (whether this is light, temperature or a chemical stimulus). The term is derived from the Latin tropus, which comes from the Greek tropos, meaning ‘turn’ or ‘direction’, and ultimately from the Sanskrit trepate, meaning ‘to be ashamed’. In the Sanskrit origin we can see a metaphor, an implication of expressive movement.

The heliotropism of the sunflower has given rise to many myths and legends. The immobility of the body and the hypnotised mobility of the flower/head/eyes suggest a contradiction that becomes expressive. Walter Benjamin, writing in 1940, could not resist this metaphor: ‘As flowers turn toward the sun, by dint of a secret heliotropism the past strives to turn toward that sun which is rising in the sky of history.’17

The association of light with knowledge, good, heaven and suchlike and of darkness with ignorance, evil, hell and the like is as old as memory and history can tell us. Considering its place in ritual and effect on our emotions, it is small wonder that light should play such an important role in mise-en- scène and that heliotropism has its place in the arsenal of expressive movements. Its opposite, apheliotropism, has the equivalent expressive value in absorbing light and seeking darkness.

Geotropism and apogeotropism are the tendencies of pulling towards and away from the earth. In terms of acting, they can indicate the heavy gesture borne down by its own weight, and the supporting, or the rising and floating gesture.

These are all reactions to external stimuli, but some of the most subtle forms of plant behaviours are nastic movements. These are movements of flat parts such as the leaf or budscale, which are oriented toward the plant rather than to an external source. They are brought about by disproportionate growth or increase of turgor in the tissues of one surface of a part, and typically involve a curling or beading outward or inward of the whole part in a direction away from the more active surface.

The curling of figures in Chola bronzes, the lotus opening gesture in Indian dance mudras (either representational or metaphoric), the graceful curves of our floral decorative motifs, all celebrate the expressivity of the movement motif. Lower organisms which exhibit forms of movement like taxis and kinesis need to be studied for their expressive potential and transformation into human gestures as well as to understand the phenomenon of expressive movement at all levels of life. As we trace the Descent (or Ascent) of Man, we find a complex relationship between the expression of emotions in animals and man.

Eisenstein’s very first theoretical article proclaimed his interest in circus. The term ‘attraction’ in ‘The Montage of Attractions’ refers to the circus; and his first important article on cinema, recently discovered and published in its entirety, is similarly entitled ‘The Montage of Film Attractions’.18 He retained this interest in circus until the end of his life. It fascinated him as a ‘plotless’ spectacle, in which each event was an attraction, an aggressive movement producing a certain shock. He saw it as a metaphor of Man’s evolution, with the animals, acrobats and clowns all affecting and moving the spectator at a very deep level, regardless of age, sex or culture. He writes about it with great feeling:

What causes people to throng to the circus every night all over the globe? […]

And each of us recalls, if not with his head and memory, then with the aural labyrinth and once bruised elbows and knees, that difficult period of childhood, when almost the sole content in the struggle for a place under the sun for all of us as a child was the problem of balance during the transition from a four-legged standing of a ‘toddler’ to the proud two-legged standing of a master of the universe. An echo of the child’s personal biography, of the centuries past of his entire species and kind.19

The Strike contains many examples of his use of the expressivity of animals. Sometimes this use is primitive, representational, eccentric, as in the case of the police spies: Owl, Bulldog and Monkey. But he also uses it tragically with the rolling eye of the dying bull in the slaughter scene.

The association of animals with human beings to express certain qualities of the latter (or, for magical purposes, to acquire certain qualities of the former) goes back to pre-history. Language retains its traces in such expressions as ‘lion-hearted’, ‘feline grace’, ‘preening’ and many others. And Darwin’s classic study, The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals (1872), showing how many human gestures and expressions cannot be understood unless we see the connection through evolution with other species, was important for Eisenstein.

In fact Ivan the Terrible reveals more significant use of animal gesture and symbolism. Leyda reproduces a Hiroshige woodcut from One Hundred Famous Places in Ido showing a hawk swooping and notes the striking similarity between this image found in Eisenstein’s scrapbook and the famous profile of Ivan in the foreground with a serpentine line of people stretching into the background.20 The whole film is charged with the vitality of animal movement: elongated necks, flashing eyes, snakelike sinuousness, the swooping flight of birds of prey, as well as such specific objects as the swan-shaped banquet servers. These are not just relics of our evolutionary past but relate to the beasts we harbour within.

The arts of India are rich in examples where the expressivity of animals is used. Jataka tales and their depiction in painting, the Narasimha legend, Nagas and Yakshas are only a few examples. But some of the most interesting cases are found in traditional dance forms, either at the level of mimesis or as sophisticated metaphors. Dances like Kathakali, which depict the demonic and the godly with the same strength, use the animal gesture to reach a truly cosmic range of expression. Indian cinema too, when it stops tinkering with poor imitations of reality and aspires to unleash the same mythic forces which have shaped the other art-forms, will find rich treasure in these forms.

As can be seen from the remarks on circus already quoted, Eisenstein was interested in those aspects of human experience which are prior to consciousness and memory. He was particularly intrigued by what prenatal experience might contribute to art and his study of Degas’s Bathing Women analyses what he calls the ‘floating tendency’ of the figures.21 The stage of being free from the struggle for existence and enfolded in protective warmth is associated with the state of weightlessness. This perhaps leads to the conception in many cultures of heaven as a place devoid of material needs, free from all physical laws and populated by beings floating or flying freely. We may remember here Tarkovsky’s Solaris, where both real and ‘imaginary’ characters float in a state of weightlessness and the imaginary becomes more real while reality becomes dreamlike. If heaven is also associated with light and the movement towards it with heliotropism, the opposite follows that ‘lower evil species (often reptiles) are depicted as creatures of darkness’.22 This may relate to our toddler stage, with the first experience of dependence on material reality.

Freud attributed flying in dreams to the tendency observed in children of deriving pleasure from games in which they are tossed around.

Children are delighted by such experiences and never tire of asking to have them repeated, especially if there is something about them that causes a little fright or giddiness. …The delight taken by young children in games of this kind (as well as in swings and see-saws) is wellknown; when they come to see acrobatic feats in a circus their memory of such games is revived.23

But why should they enjoy such games in the first place? Freud proposes an answer:

Dr Paul Federn…has put forward the attractive theory that a good number of these flying dreams are dreams of erection; for the remarkable phenomenon of erection, around which the human imagination has constantly played, cannot fail to be impressive, involving as it does an apparent suspension of the laws of gravity. (Cf. in this connection the winged phalli of the ancients.)24

This seems to me to be a case of putting the cart before the horse, since clearly the pleasure in tossing and weightlessness would be prior to the pleasure from erection and could scarcely be the cause of it. Without going into the relative merits of each argument, let me remark that in his correspondence with Wilhelm Reich, Eisenstein complained about psycho-analysis not concerning itself with the process of construction of a work of art which gives it form, and dealing only with its symbolic stuff.25

Pre-natal experience is also very important for our understanding of convex and concave space. The world is initially experienced by the unborn child as concave: the mouth which is concave has not yet found the convex breast, but perhaps ‘feels’ the absent object. In his study of Rodin and Rilke, Eisenstein says

it is a question of the mirror-unity of form and counter-form, of relief and counter-relief. In a general way of speaking, it would seem that the fact of the unity of the concave and convex form has made incarnate and materialised two modes of knowing the essence of the phenomenon, seizing it from without and knowing it from within. Certainly, in an ideal case, the two ways would fuse into one.26

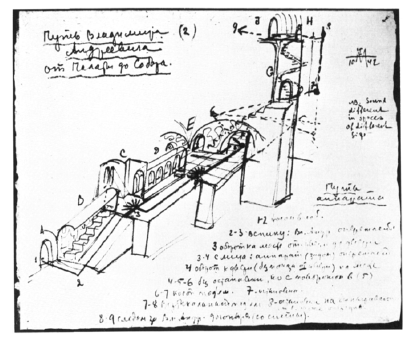

Eisenstein uses the image of passage from the womb and rejection by the mother in the last part of Ivan the Terrible, when Vladimir goes to meet his death. In fear and trembling, the lonely Vladimir moves through the colourless passage (in which Eisenstein had asked his designer to remove all angularities), knowing of the dagger that awaits him at its end. Ley da gives the plan of the original mise-en-scène for this sequence which was conceived as a continuous ten-minute shot. In it, Eisenstein united the image of the birth trauma with the death of Vladimir. After the riot of colour in the (predominantly red) feast scene, Vladimir’s face appears blue (evoking asphyxiation).27

The experience of birth is crucial for Eisenstein’s concept of mise-en-scène because it marks the meeting of so many opposites: passivity and activity, darkness and light, concave and convex space, knowing from within and without, heliotropism and apheliotropism. It creates a unity of past experience with a vision of the ideal future, and could thus be related to the iconostasis of Russian Orthodoxy, where past, present and future meet, life and death touch each other, Heaven and Hell meet.28

Eisenstein saw intonation, mimicry, gesture and movement as successive stages of human expression, each preserving something from the previous one yet also adding something qualitatively different. He derived his theory of gesture from diverse sources, from Bode, Klages, Werner, Duchenne, Delsarte, Darwin and from Freud (especially his work on parapraxis). From his (and Tretyakov’s) early translation and adaptation of Rudolph Bode, from his recently discovered early articles on montage, up to his analysis of an incident from Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, he shows a remarkable ability to synthesise diverse sources and give unity to his film practice.29 He always qualified his a posteriori analysis by saying that creation is not a deductive process. But his most interesting writings take the form of dialogues (often with himself) while searching for a creative solution.

His writings on the formal principles of composition are certainly voluminous and crammed with references to various art-forms, epochs, cultures, disciplines. Is there a method in this mad erudition? If we go back to Eisenstein’s definition of mise-en-scène, we find two key phrases: the ‘character of an event’ and ‘graphic flourish’. Identifying the character of an event, I believe, led him to search for objective principles, which would have been outlined in his book Method, along with the specific studies of how pathos is ‘constructed’ in Dickens, Disney, Chaplin, et al.

But on the other side of this apparently absolute Newtonian universe was the knower, the artist, the creator, YO. Thus his book My Art in Life leads to the memoirs, to YO! Ich Selbst.30 These memoirs are the ‘other’ of Method, where the creator reveals himself and the Absolute yields to the relativity of Eisenstein.31

Just as he brings his own subjectivity to the method of the creative process, subjectivity is a vital part of the recreative process which creates the final image in the spectator’s mind.

Before the author’s inward glance, coloured by his feelings, wanders an image which is the emotional embodiment of his theme. His task is to turn this image into two or three partial representations which by their unity and co-existence would conjure up for the reason and emotions of the spectator the same image that hovered before the author…. The spectator has to follow the same creative path which the author had to follow.