Chapter 11

The essential bone structure Mimesis in Eisenstein

Mikhail Yampolsky

I

Usually film theory acknowledges iconic quality, similarity and photographic quality as ontological features of cinema. Cinema emerges in this context as a mimetic art imitating reality. Eisenstein provides a very rare example of a radical denial of the usual notion of cinematic mimesis.

He devoted the speech he gave to the Congress of Independent Film-Makers at La Sarraz in 1929 to the problem of imitation, which he called ‘the key to the mastery of form’.1 He distinguished two types of imitation. He compared the first—the magic type—to cannibalism and utterly rejected it ‘because magic imitation copies form’.2 The embodiment of this kind of imitation was the mirror. Eisenstein contrasted this first type with a second—imitation of principle. ‘Anyone who sees Aristotle as an imitator of the form of objects misunderstands him’, he declared and added, ‘The age of form is drawing to a close. We are penetrating matter. We are penetrating behind appearance into the principle of appearance. In doing so we are mastering it.’

This statement contained the two complementary hypotheses that were fundamental to the whole of Eisenstein’s subsequent aesthetic: (1) the need for culture to pass beyond the ‘stage of form’, of the external appearance of objects and therefore primarily of ‘mirror-image’ mimesis; and (2) the stress on imitation of the principle behind objects. This latter formulation was rather enigmatic. What exactly was this principle (or, as Eisenstein liked to say, this ‘order of things’)? How could it be revealed? Where was it concealed? In the same speech Eisenstein proclaimed it to be the result of analysis (‘Symbolism in myth is giving way to analysis of/in principle’). But what kind of analysis was it whose result had to be imitated?

Eisenstein’s speech in La Sarraz coincided with his enhanced interest in protological forms of thought which later played an increasingly important part in his theorising. In his research Eisenstein turned to the group of linguists, psychologists and ethnographers who had posed anew the old problem of the origin of language and thought. Walter Benjamin called the ‘theory’ of these scholars (Bühler, Cassirer, Marr, Vygotsky, Lévy-Bruhl, Piaget, etc.—these were all very relevant names for Eisenstein) ‘mimetic in the broadest sense of the word’ because, according to the majority of these scholars, language derived from some primeval action that was imitative in character.3

It was essential to find in this mimetic action at the undifferentiated stage of thought a reflection not merely of external form but also of primeval generalisation (obobschenie) or ‘principle’, to use Eisenstein’s terminology. In the books he had collected that dealt with the problems of ‘protologic’ he consistently underlined the places where the quasiintellectual character of primitive mimesis was mentioned.4

Reading Emile Durkheim, Eisenstein’s attention was drawn to the passage where the French sociologist had analysed the abstract geometric depiction of totems among the Australian aborigines:

the Australian is so strongly inclined to depict his totem, not because he wants to have in front of him a portrait that constantly renews the sensation, but quite simply because he feels the need to represent the idea that he depicts through a material sign.5

Andrew Lang, whom Eisenstein was also reading, devoted considerable attention to the problem of imitation and concluded, ‘“Savage realism” is the result of a desire to represent an object as it is known to be, and not as it appears.’6

But how is an idea or principle instilled into archaic representation? Eisenstein was hypnotised by the passage in Lévy-Bruhl’s Primitive Mentality where he talks about Frank Cushing’s work ‘Manual Concepts’:7 ‘To speak with your hands is to some extent literally to think with your hands. The most important signs of these “manual concepts” must therefore be evident in the sound expression of the thought.’8 But, we add, if this is true of the sound expression, it will naturally be true to an even greater extent of the depiction of the thought. In Jack Lindsay’s book, A Short History of Culture, Eisenstein underlined the passage: ‘out of the harmoniously adopted movements of the body are mental patterns evolved.’9 The grapheme that fixes the gesture or movement as the generator of the ‘manual concept’ is the line. Because of this Eisenstein attributed a very special significance to the line. By drawing a line, or ‘running his eye’ over it, to a surprising degree man got to the heart of the matter, to its sense. Eisenstein wrote: ‘it is quite natural to “think” in a deintellectualised way: running your eye over the contours of objects is an early form of rock drawing and is closely linked…to the cave paintings which are linear!’10

Eisenstein came to his own kind of pangraphism by discovering in all the infinite variety of the world a meaningful line beneath the visible surface. Line was revealed in music as melody, in theatre staging (mise-en-scène) as the movement of the actors, in literary subject-matter (syuzhet) as plot (fabula), in rhythm as invariant schema, and so on. ‘Line is movement.… Melody is like a line of chords, like volumes of sound pierced and strung together. The plot intrigue and subject matter are here like contour and spatial relationship.’11 Elsewhere he wrote:

we must learn to grasp the movement of a particular musical passage and we must take the trace of this movement—that is its line or form—as the basis for the plastic composition that should correspond to that particular music.12

The line and schema were seen by Eisenstein as the obobshchayushchii osmyslitel’, the factors that gave a phenomenon its meaning in context. He observed that they represented ‘relationships in the most generalised way. The generalisation thus remains so great that it becomes what we call abstraction.’13 Even the meaning of such abstruse things as ancient Chinese numerical concepts could be understood if we were to ‘translate them into geometric outlines’ and ‘represent them graphically’.14

The line and schema had the ability to combine the abstract character of geometry and mathematics (the sphere of pure ideas) with emotional visibility (naglyadnost’). In the final analysis Eisenstein frequently conceived the very idea of ‘image’, which was so central to his theory, as a graphic schema. In his draft essay, ‘The Three Whales’, he talked about the three basic elements that underlay a visual text:

- The depiction.

- The generalised image.

- The repetition.

In its pure form the first is naturalism, the second a geometric schema and the third an ornament.15

As we can see, the image was here directly equated with a geometric schema which was also the basis of the Eisensteinian theory of metonymy (the famous pars pro toto), because ‘one facet (N.B. facet=line!) here stands for the whole’.16

The linear nature of the ‘image’ allowed Eisenstein to elaborate the concept of the general equivalence of different phenomena on the basis of the similarity between their internal schemas. It was this concept, based on the psychology of synaesthesia and essential for the construction of the theory of montage, that linked together not the surface appearances but the inner ‘graphemes’ of objects. Characteristically Eisenstein wrote, in response to criticisms by Hanns Eisler and Theodor Adorno of the theory of ‘vertical montage’, which linked sound and image:

Eisler thinks that there is no common denominator between the pair: galoshes and drum (even though a linear connection is possible, for instance).… Image is transformed into gesture: gesture underlies both. Then you can construct whatever counterpoints you want.17

The connection between galoshes and drum was possible because they were joined not by their surface appearances but by their images, the linear patterns that organised their gestures. A model for this general equivalence, based on Eisenstein’s schema, is provided by Hitchcock’s Spellbound in which an abstract ‘pattern of black lines crossing a white surface’ permitted us to establish an equivalence of meaning between a fork, a robe, a blanket and so on.18

The mimesis of form acted as a block to this panequivalence of objects, while in this context mimesis of principle opened up unlimited opportunities. Eisenstein quoted Guyau: ‘Image is in effect the repetition of the same idea in another form and another context.’19 Form changes. Idea, principle, image remain the same.

II

Needless to say, the reduction of ‘principle’ to a linear contour (a process that is at least contentious) raised doubts in the mind of Eisenstein himself. He admitted that he was ‘disturbed’ by ‘a coincidence between the highest abstraction (the generalisation of the image) and the most primitive element, the line’.20 He was able to avoid a regression to the archaic stage by resorting to the saving grace of using the dialectic and conclusions like the following: ‘In content these lines are polar opposites: in appearance, in form they are identical.’21 In this context appearance was subjected to a secondary criticism: it hinted too strongly at the vulnerability of logical processes. Eisenstein saw line simultaneously as a purveyor of protoconcepts and as the highest form of contemporary abstraction. This ‘dialectic’ was heavily dependent on Wilhelm Worringer’s Abstraktion und Einfühlung (Abstraction and Empathy), published in 1908, which resolved a similar problem in a similar fashion:

The most perfectly logical style, the style of the highest abstraction, of the strictest exclusion of life, is characteristic of peoples at a primitive cultural stage. There must therefore be a causal link between primitive culture and the highest, purest and most logical art form.22

It was from this perspective that Eisenstein persistently tried to separate the protological from the highly abstract element in line. He analysed the so-called ‘rock-drawing complex’ and tried to determine the boundary between the mechanical copying of a silhouette and contour as abstraction.23 He viewed ornament as a synthesis of the protological (repetition) and the ‘intellectual’ (geometrism).24 But none of these attempts to separ-ate the high from the low was particularly convincing. Although he declared that the revelation of a ‘principle’ was the result of analysis, in practice it was achieved through imitation or mimesis. In order for the eye to ‘think’ in contour you have to repeat the movement traced by the hand. In order to comprehend the essence of Cushing’s ‘manual concept’ you have to ‘restore your hands to their original functions, forcing them to do everything that they did in prehistoric times’.25 To Imitate a principle is to master it. But all that gave a particular status to the science of analysis. Mastering the essence of a principle acquired the character of sympathetic magic. In this situation the artist took on the mantle of a magician, a shaman, a clairvoyant, while the ‘principle’, the idea, was transformed into a mystery, an enigma which had to be solved.

This theme was most fully developed by Eisenstein in his article, ‘On the Detective Story’:

What is the essential difference between a ‘puzzle’ and a ‘clue’? The difference lies in the fact that a clue provides the name of an object as a formula, while a puzzle presents that same object in the form of an image woven from a certain number of its attributes.… Anyone who has been initiated into its great mysteries can as an ‘initiate’ master to the same extent both the vocabulary of ideas and the vocabulary of images, both the language of logic and the language of emotions. The extent to which he grasps both as they approach unity and mutual penetration is proof of the degree to which the ‘initiate’ already has command of perfect dialectical thought.… He who can solve the puzzles…will know the very secret of the movement and existence of natural phenomena.… The wise man and the priest must be sure to learn to ‘read’ this ancient former language of image and feeling and not just to master the younger language of logic!26

The detective performed exactly the same magic process: he was another hypostasis of someone who had been ‘initiated into the secrets’. ‘What of the detective story?’ Eisenstein remarked. ‘The theme that pervades the genre is the transition from image and appearance to reality based on understanding. …The same form—a simple puzzle—is the kernel of the detective story.’27

The artist was just like the magician and the detective:

The artist works in the field of form in exactly the same way but he solves his puzzle in the directly opposite way. For the artist the clue is the ‘given’ fact, a thesis expressed in logical terms, and his job is to turn it into…a ‘puzzle’, that is to transpose it into the form of an image.28

This inversion of the process in the case of the artist (from thesis-schema to form) seemed destined to translate contemporary art from the sphere of the purely protological to a more rational sphere. But elsewhere, commenting on his work on Alexander Nevsky, Eisenstein recognised the ineffectiveness of this inverted process:

It is hardest of all to ‘invent’ an image when the ‘demand’ for it is strictly formulated before the ‘formula stage’. Here is the formula you need: make an image from it. The most natural and valuable way for the process to go is quite different.29

In other words the ‘puzzle’ had always to come first.

It is not surprising that Eisenstein projected the characteristics of the magician and the detective on to himself, attributing to himself a magic propensity to super-sight, the ability to perceive schemas, lines and principles through the visible surface. He wrote of the need for the special ‘night vision’, the eye of the ‘pathfinder or his great-nephew Sherlock Holmes’.30 ‘I can see ahead with unusual clarity’, he declared.31 But this particular intellectual vision, because it was linked to the internal drawing of contour, was the actual genesis of conceptual thought: ‘Even now when I write I am essentially almost “outlining” with my hand the contours of the patterns of what passes in front of me in an unending film of visual images and events.’32 This was the reason for the unexpected criticism of normal vision, which was not connected with the tactile aspect of the protoconcept, that he developed in the chapter of his Memoirs entitled ‘Museums at Night’: ‘Generally speaking, museums should be visited at night. Only at night…one can merge with what one sees and not just look at it.’33 ‘The bulb has only to blow…and you are completely at the mercy of dark hidden powers and forms of thought.’34 Eisenstein, despite his passion for painting and the ‘essentially visual nature’ of his profession, chose a particular clairvoyant blindness reminiscent of poet prophets like Homer or Milton.

Eisenstein turned to the theme of night vision even before the Memoirs in an unpublished fragment from 1934. It is significant that, after discussing the mysticism of Swedenborg,35 Eisenstein moved on by association to the idea of a multiplicity of worlds: ‘Just imagine for a moment that the light goes out and the reality around you suddenly becomes a Tastwelt [a tactile world] of perceived reality.’36 The world was divided into the world of the visible, the perceived, the heard and beyond them there was ‘a multiplicity of worlds: the world of the real [Handlungswelt], the world of the imagination [Vorstellungswelt], the conceptual world [Begriffswelt]’.37 In this multiplicity, the world of ‘things in themselves’ emerged, perceived through the veil of vision and appearance, and it was this world that the artist-clairvoyant also perceived through the magic dialectic. Once again in this mystical picture of world perception we find echoes of the old treatise of Worringer who had asserted:

It is in primitive man that the instinct for the ‘thing in itself is at its most powerful.… It is only when the human spirit has travelled in the thousands of years of its development the whole road of rational discovery that the feeling for the ‘thing in itself reawakens as the final resignation of the conscious.38

Eisenstein could not help regarding his own consciousness as having existed for thousands of years. He perceived the world like a man who had lived forever.

III

The genesis of sense from gesture, movement, tactile quality, gave the text the character of a body. It was precisely for this reason that reading a text became a physiognomic activity, something that Eisenstein referred to more than once: ‘We shall tirelessly train ourselves to sense keenly the physiognomy of one-eyed expression.’39 According to Eisenstein’s conception of the genesis of form, it was preceded by principle, schema and line, which were gradually overgrown with the body. Studying the experience of ecstasy, Eisenstein showed that the mystic dealt initially in things that were ‘imageless’ and ‘objectless’, in a ‘completely abstract image’ that then painstakingly ‘ “becomes objectified” in concrete objectivity’,40 and he pointed out that ‘the imageless “beginning” is a set of laws…and the image of a concrete and objectified “personified” god is rapidly disclosed’.41 He was talking about the almost physical discovery of the principle of flesh, the growth of the body according to the pattern: ‘The formula, the concept, is embellished and developed on the basis of the material, it is transformed into an image, which is the form.’42

Eisenstein, as was his wont, applied this metaphor to the evolution of natural bodies, whose surface he saw as a static mould made from the movement of the body, just as the line is the shape of the mark left by movement.43 In so far as the manifestation of the principle had, in Eisenstein’s view, to repeat regressively the process whereby form took shape, it constituted essentially a ‘decomposition’ of the body of the text, a peeling away of the layers of body from the idea. It was natural therefore that Eisenstein should have a heightened interest in the leitmotiv of a body within a body, an envelope within an envelope, in what he called ‘the kangaroo principle’.44 He was interested in the Indian drawing in which the silhouette of an elephant encompassed the images of young girls,45 or the enclosure of Napoleon’s body in four coffins, each inside another,46 and even in Surikov’s painting Menshikov in Beryozov he detected the metaphorical structure of these repeating coffins.47

By removing the envelope you could get to the body, by preparing the body you could get to the heart. In ‘The Psychology of Composition’ Eisenstein developed in detail the metaphor of authorial self-analysis (to which he constantly subjected himself) as ‘autopsy’, as the dissection of a corpse. It is significant that to this end he analysed ‘The Philosophy of Composition’ by Edgar Allen Poe, a writer with whom he had much in common—the mythology of the perspicacious detective, the belief in physiognomic knowledge and so on. Eisenstein equated a detective story to a pathologist’s investigation: ‘The one conducts his analytical “autopsy” (revelation) in the forms of a literary analysis of the image he has himself created while the other uses analytical deductions of the detective kind.’48 In the same context Eisenstein wrote of the transition from ‘the examination of the “decomposition” of the body devoid of life… to the decomposition “for the purpose of analysis” of the body of a poem’.49

The analytical revelation of the body of a text supplemented a physiognomic reading. The ideal became a particular ability to see through the body to the graphic structure that organised it. I would call this the method of the artistic X-ray which highlights through the flesh the skeleton concealed inside it.

The metaphor of the skeleton, of the bone-structure, was to prove extremely important for Eisenstein’s method of recognising a principle. The imitation of principle became the denial of the body in order to reveal the skeleton. It has to be said that this dark metaphor came to Eisenstein, at least in part, from those Symbolists who were involved in theosophy and anthroposophy. These recent mystical teachings were, like Eisenstein’s theory, orientated towards a particular kind of evolutionism. Genetically preceding forms were preserved, according to Rudolf Steiner for instance, in the form of invisible astral bodies that were however revealed to the ‘initiated’. The Theosophists were seriously involved in attempts to fix invisible geometric sketches of what Annie Besant called ‘forms/thoughts’ and in so doing they directly referred to the experience of X-rays.50 Maximilian Voloshin, who was close to Anthroposophy, wrote an article with the significant title ‘The Skeleton of Painting’ in 1904 in which he stated: ‘The artist must reduce the entire variegated world to a basic combination of angles and curves’, that is, he had to remove from the flesh that was visible the skeleton that had been revealed inside it.51 The same Voloshin read, for example, the paintings of K.F.Bogayevsky as palaeontological codes, seeing in them concealed prehistoric skeletons.52 The Anthroposophist Andrei Bely in his Petersburg, which is suffused with the leitmotiv of the rejection of the corporeal and the journey to the astral, provided us with a description of the movement from formula to body that is very similar to Eisenstein’s: ‘Nikolai Apollonovich’s logical premisses furnished the bones; the syllogisms surrounding these bones were covered with stiff sinews; the content of his logical activity was overgrown with flesh and skin.’53 Indeed, we note that the passage quoted ends with an episode for which the sequence of the gods in Eisenstein’s October might be taken as a paraphrase. We are talking about the scene in which the head of an ancient primitive idol extrudes through the metamorphoses of the gods— Confucius, Buddha and Chronos.54 The passage through accretions of flesh to the skeleton is analogous to the passage through appearance and the accretion of later deities to their schematic predecessor, and that is a thought process close to Eisenstein’s. On the other hand, the development of abstraction from Theosophy was a path common to many artists at the turn of the century, including Kandinsky and Mondrian.

Eisenstein admitted, ‘I have been attracted to bones and skeletons since childhood. This attraction is a kind of illness.’55 He despised the emphasis in unskilled drawing on the corporeal because ‘the finished drawing relies upon volume, shadow, half-shadow and reflex while a “taboo” is placed on the graphic skeleton and the line of the ribs’.56 Eisenstein viewed with great suspicion paintings in which flesh was used to conceal the essential bone structure. He quoted the following passage on Chinese painting from Chiang Yee’s The Chinese Eye:

suddenly they may glance at the same water and rocks in a moment when the spirit is awake, and become conscious of having looked at naked ‘Reality’, free from the Shadow of Life. In that moment they will take up the brush and paint the ‘bones’, as it were, of this Real Form: small details are unnecessary.57

Eisenstein offered the following commentary on this passage: ‘Here we encounter the word “bones”. This linear skeleton, whose function is to embody the “Real Form”, the “generalised essence of the phenomenon”. ’58 There was a direct link here between the linear schema as a principle and the metaphor of the bones. Elsewhere Eisenstein, once again comparing a schema to a skeleton, was more specific: ‘this “essential bone structure” may be swathed in all sorts of particular painterly devices.’59 In a certain sense he was also reaffirming the independence of the bonestructure from the flesh that covered it.

Since for Eisenstein any hypothesis was finally proved by projecting it on to evolution, he developed this metaphor in an evolutionary way. He quoted from Emerson’s account of Swedenborg’s teaching (Representative Men) a fantastical passage in which the entire history of evolution from the serpent and the caterpillar to man himself is depicted as the history of adding to skeletons and rearranging them.60 And in a note written in 1933 he enthusiastically revealed another fantastical evolutionary law of correspondence between a skeleton and a thought pattern: ‘Self-imitation. (Hurrah!) Shouldn’t I write about it as a process of developing the consciousness? Nerve tissue reproduces the skeleton etc. and thought reproduces action. It is the same in evolution.’61 The nervous system as the purveyor of thought graphically repeated the pattern of the skeleton as the purveyor of action. In man there occurred an internal mirror-image mimesis of the schemas, structures and principles from which consciousness derived.

Eisenstein often wrote about the way in which schemas, lines and bonestructure shone through the body of a text. This magic X-ray was rooted in the particular mechanisms of Eisenstein’s psyche. He recalled ‘only one scene’ from Frank Harris’s memoirs, My Life and Loves: the story of the man who laughed ‘and shook so much that the flesh “began to part from his bones”(!)’62 The bones literally began to stick out through the flesh. In the passage in his Memoirs ‘On Folklore’ Eisenstein recalled that he had compared a certain Comrade E to ‘a pink skeleton clad in a three-piece suit’ and he recreated the psychology of the birth of this ‘sinister image’: ‘First you picture a skull sticking out through a head, or the mask of a skull sticking out through the surface of a face.’63 Even Eisenstein himself admitted that the image ‘of the skull squeezing through the surface of the face’ was a metaphor for his own conception of expressive movement, a model for the work of visual mime. This demonstrates why the physiognomic perception of the essential was so important in Eisenstein’s method. The science of physiognomy counted bones through accumulated layers of flesh. But from that it was only one step to his concept of ecstasy, which may be understood as exstasis—the removal of the skeleton from the body, the principle from the text, the emergence of the body from itself, like ‘the skull squeezing through the surface of the face’.64

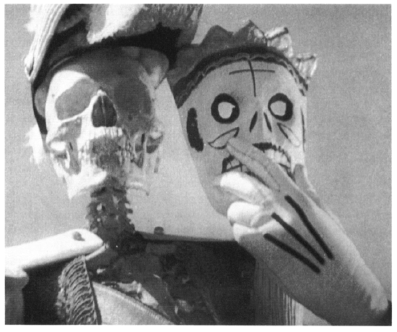

The skeletal motif appeared in his films as well, in Alexander Nevsky and above all in Que Viva Mexico! In the scene of the ‘Day of the Dead’ in the Mexican film the ‘essential bone structure’ was transformed into an extended baroque metaphor. For Eisenstein the fact that the carnival death masks revealed real skulls was of decisive significance:

Both the face like a skull and the skull like a face.… One living above the other. One concealed beneath the other. One living an independent life through the other. One in turn shining through the other. One and the other, repeating the physical schema of the process through the play of images of face and skull, of changing masks.65

The meaning in this constant play of physiognomies emerges through the flesh (mask) to become in its turn a mask. The essence of Eisenstein’s concept of mimesis is concentrated in this image.

Research that concentrates attention on the montage stage of Eisenstein’s semantic conception usually fails to link it properly with the Grundproblematik. However the montage stage of the creation of meaning in his conception would be unthinkable without the first stage of mimesis of ‘principle’, of the revelation of the schema, of the intellectual grapheme that fixes image and protoconcept. This initial stage of the creation of meaning depends on the intuitively magic physiognomic disclosure of the line which lies concealed within the body of the object (or text)—of the ‘bone-structure’. Before the intellectual manipulation of the montage stage the artist passes through the ‘corporeal’ stage of creativity, which Eisenstein described as ‘decomposition’, an X-ray ‘autopsy’ of the visible, the flesh. Before we can begin to combine generalised image schemas, the ‘all-important bone-structure’, visible to the ‘initiate’, must ‘elbow its way’ through the face of the world around us.66

Translated from the Russian by Richard Taylor