Chapter 12

Eisenstein and the theory of ‘models’; or, How to distract the spectator’s attention

Myriam Tsikounas

Eisenstein’s silent films have often been described as ‘mass films’ or ‘films without heroes’. In each narrative, however, a protagonist—played by a carefully selected non-professional actor—assumes more or less definitive individuality.1

Even in 1947, Eisenstein was still recalling the time lost in searching for ‘types’, in wearisome rehearsals and in make-up sessions required to ‘hide the little mole-eyes of a Sebastopol boiler-man and transform him into the ship’s doctor on the Potemkin’.2 So why did he spend over seven years recruiting non-professionals, or parading members of his production crew like Maxim Strauch, Eduard Tisse and Grigori Alexandrov in front of the camera? What function was served by these novices who made only one appearance to illustrate the transition from the ‘old’ to the ‘new’? Was their role identical in the films of commemoration and those of collectivisation, or was it subject to a dual evolution, both chronological and political?

In order to answer such questions, I shall attempt, after defining the features common to all these newcomers, to trace the itinerary that stretches from the dawn of the century (The Strike) to 1929 (The General Line/The Old and The New) and is signposted by two dates: 1905 (Potemkin) and 1917 (October).3

All four epics do in fact follow a similar pattern. In each, the first act sets the scene and even invites a charge of archaism. The ‘model’ naturshchik does not really put in an appearance until the second part. Then the action lingers upon him, immediately establishing him as both a semiotic and agential subject.4 As a victim of injustice, the individual rebels and leaves his station to confront the old world. He may be mocked or killed, but none the less triggers a general mobilisation which reprogrammes the narrative. These emblematic figures—respectively a worker, sailor, a Bolshevik militant and a poor peasant woman—also share the characteristic of evolving alongside a counterpart who opposes, takes over, or aids in the fulfilment of their civilising mission.

THE WORKER IN THE STRIKE

The pretext for the strike, with which the second part of the film opens, is a false accusation. A worker, introduced in close-up, looks vainly–in a methodical alternation of seer/seen– for the micrometer which has just been stolen from him. He makes the audience a witness by means of a glance to camera. Two intertitles convey his thoughts–‘A micrometer costs 25 roubles’ and ‘Three weeks work for the Tsar’–and a third emphasises his quest: ‘He goes to complain to the office.’ There, in a series of action-reaction exchanges, the actor confronts the foreman and the manager. Accused five times of being a ‘thief, he walks out, staring intently at the camera. The action leaves him to concentrate on the other actors, still glued to their machines. When we return to him, he has hanged himself but, in committing suicide, he has also acquired a name and transformed himself into a catalyst, calling on his workmates to repair the injustice by downing tools.5 This summons has an immediate effect on the film’s graphic style. The workers’ bodies are fragmented into close-ups of legs running, angry faces, hands downing tools. Solidarity is expressed formally as the word is passed from one to another. Three extras, symbolising three generations, fold their arms in front of a wheel which stops turning. For the first time, actions succeed each other logically. The group retraces the victim’s path and spreads through the factory with the cry: ‘To the office, comrades’.

The corollary to this creation of a revolutionary space is that the ‘old’ loses its place. The bosses, briefly glimpsed, are wedged between the camera and a window (which they have to close, to avoid being stoned). But the crowd does not assume control of the narrative for long as we return to a system of opposing parallels in the next act.

While the workers hold an interminable meeting in a clearing, management is already preparing its response and, in the fourth part, the starving people are confined to their homes. At which point, enter ‘the ragged proletariat’—their a priori opposite in every respect. The workers, who all appear alike, live with their families in a clearly defined district; while the motley elements of the ‘lower depths’ live alone, each in his underground barrel. Set design and editing, however, do their best to blur this contrast. The two camps, presented alternately, conspire in similar settings and boast exactly the same number of ringleaders. While four workers and a woman grouped near some casks formulate a plan, the ‘King’ summons four beggars and a whore from huge drums half-buried in the ground.

Above all, this underworld has its own individualised character who, throughout the narrative, derives his power from his metaphorical presence. First placed on screen by the police chief as he consults his file of informers, ‘Owl’ emerges from the book of mug-shots to hang up his hat and salute the audience. While spying, he hides among ropes which are progressively enlarged in a play upon perspective, or disappears into tombs and, in protean fashion, reappears metamorphosed into an eagle perched on a parapet. In the fifth act, this bird of prey takes control of the narrative. It is through his eyes that we discover the ‘court of miracles’ and when he photographs ‘the dangerous ringleader’ the action is set in motion. He develops the film ‘that same day’, sets a trap ‘in the evening’ for the worker, who falls into the ambush ‘at night’. ‘In the morning’ he congratulates the police, who are beating up their prisoner and ‘the following night’ he gloats over his success, commenting ‘They’ve had it’. After disappearing for a time, he returns to give the signal for repression to start. During the ‘liquidation’ he laughingly supervises the operation alongside the police chief.

The masses appear to be playing the central role in The Strike, but in fact it is just two individuals who manipulate the narrative. The first, established as a catalyst, encourages the emergence of a ‘plural actor’; the second, his opposite, reins in this group and guides it towards its destiny—death. The strike fails not only because the old has not been undermined, but also because in this struggle, victims and executioners are counterparts, occupying the same place at the bottom of the social scale.

THE SAILOR IN POTEMKIN

The film offers an early identification: ‘The sailors Matyushenko and Vakulinchuk’. These are introduced together and presented as twin.6 They are first observed in parallel action in the sleeping quarters. The first, described as ‘vigilant but blundering’, strikes a cabin boy. The second, represented by an intertitle in huge letters, stirs up the crew and the montage indicates the efficacy of his speech. His every phrase (transcribed by a title) is followed by a shot of a sailor waking and agreeing with him. In the next section, the over-impulsive Matyushenko withdraws to the wings; Vakulinchuk monopolises the screen. ‘In the morning’ he criticises the food and urges the men to leave the mess. When Captain Golikov decides to put down the mutineers, the militant takes charge of operations and ensures victory by undermining the two tsarist symbols: the church and the army. His tactic becomes the subject of the whole second act.

As the episode starts, Admiral Gilyarovsky, framed to advantage (in low-angle close-ups against a white background), orders the quartermasters to execute the mutineers. Hesitating, the young sailors notice in reverse angle a priest ‘descending from Heaven’. His appearance is stormy, with furrowed features haloed by a long white beard. As he holds out the crucifix and entreats, ‘Lord, let the unruly submit’, Gilyarovsky gives the order, under God’s decree, to open fire on the tarpaulin which has been thrown over the mutineers. Time is stretched so that the various reactions may be recorded. Vakulinchuk lowers his head; the firing-squad takes aim; the priest complacently toys with his cross. But the sailor lifts his head and sees a sequence of six detail shots (the ship’s bows, tarpaulin, buoy, bugle, crucifix, firing-squad) symbolising the Potemkin and/or the ‘old’. Vakulinchuk ‘makes up his mind’, which determines the precise timing of the outcome. The military command ‘Fire!’ is countered by ‘Brothers! On whom are you firing?’ The command ‘Beware the Lord’ is irreverently answered by ‘Go to hell, fool!’

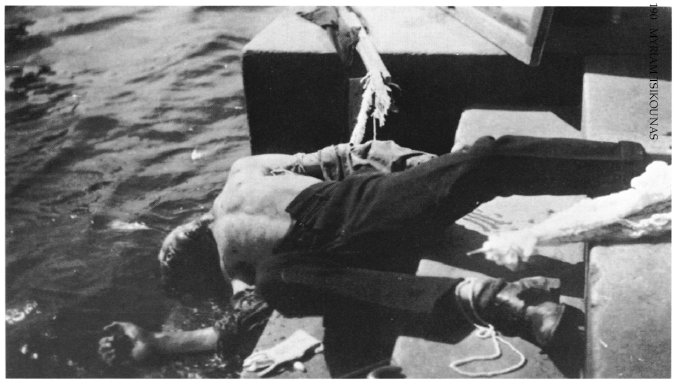

This last is enough to rout the foe. Suddenly filmed from behind in highangle long shot, Gilyarovsky gesticulates on the bridge. The prelate no longer has his head in the clouds, but now emerges from the ground. He attempts the painful climb from the bowels of the ship. When Vakulinchuk strikes him, he resorts to nervous mannerisms—fearfully he peers out of one eye, then closes it again—and his cross buries itself in the deck like an axe. Demythologised, tsarism may now be capable of destruction. The sailors fraternise with the firing squad, arm themselves, throw the officers into the sea and ransack their cabins. Seemingly embarrassed, however, the narrative seeks a way to neutralise this wilful, self-appointed leader—the very embodiment of subjectivity and all those characteristics opposed to the idea of a vast social movement. It finds a solution. The act closes on a fade-out and reopens with a sacrifice. Vakulinchuk, shot (in the back) by Gilyarovsky, in turn falls overboard and it is on his face—smeared with impure blood and to be avenged—that the ‘drama at sea’ definitively closes.7

This volte-face enables the narrative to alter direction. ‘The dead man who demands justice’ becomes the key to the fate of the crew and the people of Odessa, summoned to unite in solidarity. The film changes gear. We turn from ‘one cell in the battleship’s organism to the whole ship as an organism; from a lone appeal for fraternisation to the ship’s cry of “Brothers!”; from individual catering to collective revictualling by the yawls’.8 This broadening out also affects the Potemkin itself. Hitherto the ship has remained a fixed space and only certain parts of it have been explored; now it is seen in its entirety. It becomes animate, establishing itself territorially, and is transformed into an actor asserting its name, ‘Prince Tavrichesky’ (Taurida).

Every effort is made to humanise it. We see it taking on supplies, cleaving the water, putting on a burst of speed, readying its guns and directing its lights, looming into camera like a face. The intertitles also help to anthropomorphise it. They indicate its position, ‘The battleship is at anchor, it has mutinied’; recount its exploits, ‘It replies to the army’s atrocities’; name its adversary, ‘The battleship against Destroyer No. 267’; stress its isolation, ‘Alone against all’; and glory in its eventual triumph, ‘The battleship proudly passes the fleet without a shot being fired’.

The sailor has released a collective force which takes up and amplifies the initial revolt. The same episode on the Odessa Steps is a counterpart to the tarpaulin. Once again tsarism looms from above (and from the field of a saint’s statue and a church). Its presence is limited to a row of bayonets and giant Cossack shadows. The battleship responds equally abstractly. A single salvo blows up the Odessa Opera House, headquarters of the general staff. Ultimately, however, this ‘figurative thrust’ is contradicted by the diegetic action. We return suddenly to the Potemkin as a cockpit. Matyushenko, Vakulinchuk’s ‘double’, is bringing the ship in; not only has he taken over the captain’s cabin and assumed the authority to shout orders, he has also appropriated the ‘old’ equipment: optical instruments, telephones and maps.

The ‘writing’ (écriture) of Potemkin sets two worlds formally in opposition, but semantically it shows a simple transfer of authority and the perpetuation of ritual, suggesting areas of permeability.

THE STANDARD-BEARER IN OCTOBER

Like the worker and the sailor, the man carrying the banner who appears on the scene in the second act of October, during the ‘July Days’, is briefly established as both a semiotic and agential subject. Introduced by the title ‘Saving the flag’ and described as a ‘Bolshevik’, he also acts on an individual basis as he irrupts into the ‘other scene’.9 Cast in the role of a voyeur, he intrudes on the intimacy of an officer and his female companion, who are shown in three subjective shots. He thus undermines the old and pays with his life for his indiscretion. The bourgeois women, who have hitherto been merely spectators, now enter the action. For the first time their bodies are seen. Stamping feet break the shaft of the banner; and hands wield objects, no longer charming, but deadly as the umbrellatips serve to pierce the young man’s chest. Faces, now jarringly different, express a ‘cannibalistic rage’.10

The camera loses its panoramic neutrality to stress the hysteria of those who shift the responsibility for their own confusion on to a third party. Furthermore, the displacement effected from the Bolshevik to his banner (torn to shreds by teeth) and then to the organ of his party (the copy of Pravda thrown into the water) reveals their lack of ideological purpose. Contrasted with this old-fashioned lynching of a militant, enlightened but possessed of an unhealthy subjectivity, is the death of two innocent emblematic victims: a woman and her horse.11 This female extra, whose face remains hidden and who cannot be assigned to any particular camp by particularities of clothing, is killed on the dividing line between the spans of a bridge as these are raised. She thus rejoins the people on whose side she falls.

These three deaths reprogramme the narrative. The old world, however, continues to show its hand. At the end of the scene a minister pointlessly reissues the order (which has already been executed) to ‘cut off the workers’ quarters from the centre’.12 In the next section, an entire regiment is described as having gone over to the Bolsheviks, yet the Party headquarters is ransacked and its leaders are arrested in large numbers.

The ‘July Days’ give a starring role to the masses. However, if we consider the overall organisation of the film, this sequence, sandwiched between Lenin’s arrival at the Finland Station and Kerensky’s installation in the Winter Palace, also seeks to distract the spectator’s attention and make him forget that historical change is effected by two figures alone.

The vanguard introduction of Lenin by a date title, ‘The 3rd of April’, immediately designates him as capable of changing the course of events.

By graphic artifice, the letters ‘HO’ (but) which follow the titles ‘Everything is as before’ / ‘Famine and war’, change to ‘OH’ (he), ‘Ulyanov’, ‘Lenin’. Like the statue of Alexander III which is dismantled/ reassembled on 17 February, the actor is introduced in piecemeal fashion. We see his foot on a running-board, followed by an oblique shot of his body, cut off from the waist by a banner. His space, on the other hand, is constructed as the reverse of the Tsar’s. The monarch was seated in an empty, overexposed frame, whereas Lenin is standing at night in the middle of a dense crowd, whose immobility contrasts with the raging elements of wind and light. Behind him stand not cupolas, but the precise time on a clock.

Kerensky’s downbeat introduction could not be more different. Unlike the Bolshevik leader—hailed by the people shouting his name—the head of the Provisional Government is supported by no-one. It is the film which names him and enumerates his titles: ‘Supreme Chief, ‘military and naval’, ‘Prime Minister’, ‘etc.…etc.…etc.’ He is presented whole. Seen from behind, he plunges into a corridor, then ascends an interminable staircase. Associated from the outset with statues of women, the actor is soon confined to female quarters. The narrative insistently stresses that Kerensky is occupying the apartment of his namesake, the empress Alexandra Fyodorovna. The two men are soon engaged in a system of parallels. While the latter surrenders himself to the luxury of the royal furnishings and tableware, the former asserts his metonymic force. Of the revolutionary in hiding, we see only the Finnish hut, then the disguise. The argument is clear. Kerensky has chosen the palace of the Romanovs as his residence, but he is unfit to replace the Father of Russia, whom only Lenin is capable of thwarting.

Here again, though, displacements come into play. Although Ulyanov, the bearer of a programme, sets himself in opposition to the old world right from his first intervention, by the end of the film, standing on the rostrum, ‘he draws his strength from his inscription within an institutional form [unless it be] the strength of the institution which henceforth subsumes the man.’13

THE PEASANT WOMAN BETWEEN THE OLD AND THE NEW

The peasant Marfa Lapkina is also introduced in the second act by two intertitles which name her and list her meagre chattels. Like her predecessors, she has an undeniable agential efficacy. As soon as she appears on the scene, the narrative stops marking time and starts to make rapid progress. Having left ‘in the spring’ to beg a horse from the kulaks, the woman returns empty-handed ‘in the summer’, and proceeds to harangue the villagers. The proposed co-operative is established with the help of two technicians from the city, who are introduced identically–in frontal close-up–after a title has noted their occupations. The Secretary’ promptly disappears from the diegesis, while ‘the Agronomist’ supports the heroine in her civilising mission.

At first Marfa seems to be helping the Agronomist, making people forget that the actual decision was authoritarian. The act closes with a fade-out on the man declaring the kolkhoz constituted, despite the negative vote of the poor peasants, the ‘bednyaks’; but a kind of appendix reopens on the woman seated beside the only three sympathisers and closes with an iris on her smiling face. This schema is reversed during the second mission: learning how to use a cream separator. Marfa’s spontaneity, her ‘sensual, almost animal joy’ is checked by the Agronomist, who cuts the miracle short by addressing a laconic ‘I congratulate you’ to the new members, doffing his cap in salute.14

When it becomes necessary to combat resurgences of the ‘old’ in the ‘new’, the two protagonists are once again placed in parallel. They enter the dairy in similar manner and both face the same task. Each must convince the peasants to return their hastily withdrawn profits and confront (in shot/reaction shot) the most stubborn of the muzhiki. Marfa slaps an old man and raises the real problem: money. She lectures them: The cooperative’s money must not be spent’, ‘It would be wasted to no purpose’, ‘Give back the money’. The peasant, deaf to what she is saying, throws her to the ground. Providentially, the Agronomist appears and, hammering with his fist on the table, rallies the irresolute by sketching out a programme: ‘What about the pedigree bull?’, ‘What about improving the breed?’ He stares at the stubborn co-operative member, who lowers his eyes and returns his share.

A transference has taken place. Marfa has proved ineffectual and would be no more than an illusory heroine, except that a sudden shift in the narrative restores her to the central role. Dozing by the box of money filled at such cost, she dreams that she is in a collective of the future and there finds ‘the pedigree bull’. But in fact Marfa has forgotten the object of her original quest—agriculture—in order to adopt a second goal dictated by the Agronomist, that of breeding livestock. Moreover this promised land of milk and honey is predicated on a lack: it is peopled only by women. The sleeper awakes ‘in the autumn’ and realises that the agricultural implements have still not been delivered.

The Agronomist joins her one last time and persuades her to go to town to get a tractor. Having set this goal, he withdraws to the wings and his place is taken by the waiting secretary, who accompanies Marfa to the ministry. The two characters share the same point of view. Simultaneously they see the portrait of Lenin and an official already in frame. But the man acts alone and, when he proposes to ‘lay down’ a ‘general/line’, Marfa, as at the beginning, staves off violence by enthusiastically concluding, ‘Thanks to the workers’. Their buttressing job over, the two aides finally leave, delegating their role as catalyst to the now-civilised heroine. Returning to the village, Marfa hurries to the assistance of the tractor driver who is repairing the defective engine. The spectator, whose attention has been distracted throughout, does not notice that in order to reach this dénouement the protagonist has renounced first cultivation and then livestock to devote herself to machinery. He also does not see that the Agronomist, who assures the continuation of work on the land, has been supplanted by the Secretary, an embodiment of industrialisation.

Moreover, the two epilogues that Eisenstein offered are in fact irreconcilable. In 1926, Marfa benefits from the action taken: she has begged for a horse and is given a tractor. She climbs up and takes the place of the new man to drive the newly-acquired vehicle and present herself to the audience, who once again see in a series of recapitulatory close-ups the various stages through which she has passed during the story. In 1929, on the other hand, Marfa merely sits beside the tractor-driver, masking this urban interference. She disappears immediately after, since we leave the countryside for a Taylorised factory. To counter the absence of an agential subject, the film-maker concludes, non-diagetically, with a series of titles addressed directly to the audience.

We can now better understand why, despite the enormity of the work involved, Eisenstein committed himself to using ‘types’. In each film a character embodying a will and a conscience is established and then progressively challenged or put to death. The essential function of this mirror image is to mask the narrative’s real beneficiary, a double who pulls all the strings, hiding behind the man (The Strike, The Battleship Potemkin, October) who risks his life to challenge the ‘old’ on his behalf; a double who reveals (and duplicates) himself to protect the woman (The General Line) of whom he asks only that she mitigate the violence employed.

Translated from the French by Tom Milne