Chapter 13

Eisenstein and the theory of the photogram1

François Albera

I want to investigate an aspect of Eisenstein’s theory that has been little discussed—not least because Eisenstein himself scarcely developed it in his writings—yet which relates to what he called in the 1937 essay ‘Montage’, the ‘fundamental problem of cinema’.2 This is the illusion of movement created by cinema, the ‘movement effect’ or, as it is now often termed, the ‘phenomenon of apparent movement’ (phi-effect).3 Although this ‘effect’ is often invoked to explain the phenomenon of the impression of reality, Eisenstein referred to it in his definition of montage at the point where he was elaborating his theory of ‘intellectual cinema’.

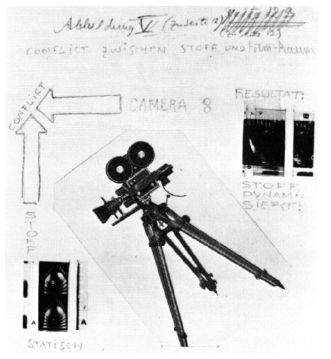

It was in a speech prepared for the 1929 Stuttgart ‘Film und Photo’ exhibition (and intended for publication in German in the catalogue) that he first raised the issue.4 He mentioned it again briefly in a preface to Vladimir Nilsen’s 1933 account of trick photography and at greater length in the second chapter of ‘Montage’, where he made fundamental changes to the original Stuttgart formulation.5 In 1929 Eisenstein wrote: ‘For here we seek to define the whole nature of the principle and spirit of the film from its technical (optical) basis.’6 And what is this ‘technical (optical) basis’? ‘We know that the phenomenon of movement in the film resides in the fact that two motionless images of a moving body following one another in juxtaposition blend into each other after sequential showing in movement.’

The significance of this reference to the technical-optical foundation of cinema lies in its recognition of the photogram, which is neither designated as such, nor by any other technical term, but simply as an ‘immobility’ (Unbeweglichkeit). A secondary relevance is the mode of articulation between these technological unities alongside the mechanical process propelled by the machinery of cinema.

Two shot immobilities next to each other result in the arising of a concept of movement.

Is this accurate? Pictorially—phraseologically, yes.

But mechanically the process is otherwise.

For in fact each sequential element is shot, not next to the other, but on top of the other.

For: the movement-percept (feeling) arises in the process of the superimposition on the received impression of the first position of an object of the becoming-visible new position of the object.

The still images do not succeed or follow one another in order to fuse, mix or dissolve in motion; they are superimposed, as in printing (Eindruck, or ‘impression’, is the term used in engraving). The choice of this term allows us to establish Eisenstein’s most basic conception of montage, dating from the period of his 1923 manifesto ‘The Montage of Attractions’, when he was thinking in terms of photo-montage (and referring to Rodchenko and Grosz).7

This is why, after a description of the base phenomenon in terms not of the frame sequence but of the superimposition of frames, he can challenge Kuleshov’s and Pudovkin’s conception of a montage chain with his montage collision: ‘According to my opinion, however, Montage is not an idea recounted by pieces following each other, but an idea that arises in the collision of two pieces independent of one another.’ This sentence and the idea it expresses are well known; they had already appeared in Eisenstein’s 1929 article ‘Beyond the Shot’.8 But again it is worth noting his precise formulation in the Stuttgart text, specifically (a) the importance attached to the ‘piece’ or element (Stück) and to the independence from one another of the kadr or Bildausschnitte as photograms (the English manuscript actually bears an autograph insertion after ‘independent’: ‘even opposite’);9 and (b) the convergence between their mode of articulation and that which prevails in the system of language, via reference to the Japanese or Chinese hieroglyph.

‘Beyond the Shot’ is dominated by questions about the relationship of representation. The problem of the referent—how ‘the combination of two “representable” objects achieves the representation of something that cannot be graphically represented’—is the origin of a problematic which will later come to dominate Eisenstein’s thought, namely the distinction between representation and the ‘global image’ (izobrazhenie and obraz), and will eventually ‘cap’ the theory of ecstasy.10

‘Stuttgart’ states only that ‘two independent ideographical signs (‘Shots’), placed in juxtaposition, explode to a new concept.’ Thus Eisenstein locates the minimal space of filmic articulation between frames, rather than between shots. Two frames which follow each other in super-imposition can differ minimally (A1+A2+A3…), to a greater degree (A1+A15), or can be totally disjunctive (A+B or Z). In the first case, movement will seem continuous; in the others it will be increasingly intellectualised, to the point of becoming a purely filmic movement, as in the example of the young peasant at the end of October who jumps with joy on the Tsar’s throne. Here there is ‘movement’ in the form of a violent displacement of the subject from one side of the frame to the other without any transition.

To define the frame sequence as a sequence of successive phases of real movement, broken down into stills and reconstituted by projection, is thus to describe only one case and to capitulate to the dogma of continuity, to the flux of ‘Life’ that Bergson’s philosophy celebrated.11 The claims of conflict, discontinuity, omission and heterogeneity all challenge a Bergsonism which was evident in the first writings on cinema by Viktor Shklovsky. The consequences of these theoretical positions for Eisenstein’s cinematic practice are largely to be found in the experimental sections of October (which were inserted during the second phase of its editing, after the first presentation during the 1927 anniversary) and in The General Line. They can be summarised as follows:

- An emphasis on static objects: the material object (veshch’), which was central to the discourse of the Constructivist and Productivist avantgarde, tends to occupy the place of the object of perception (predmet), hence such ready-made images as emblems, illustrations, icons. As early as his ‘Montage of Film Attractions’ (1924), Eisenstein distinguished theatre’s concern with what is made from cinema’s reliance on conventional images (photographs).12

- (a) Attention to the cinematic mechanism—the row of regular units that constitute the film strip—leads to frequent self-referentiality: revelations of the process by means of slow and fast motion, repetition, temporal and spatial mismatches, and

(b) the privilege accorded to the creation of any movement other than that of illusionist ambiguity, which is deemed naturalistic. The animation of inanimate objects—like the famous rampant stone lions and the plaster Bonaparte—but, more disturbingly, the tendency to make a movement or gesture something filmic rather than filmed. In addition to the peasant boy on his throne, October includes the example of the firing machine-gun created by the rapid juxtaposition of very brief still shots, reduced almost to single frames, of the gunner and his gun. The collision of frames whose plastic components—composition, geometric structure (which Mikhail Yampolsky has also noted in this volume), luminosity, etc.—these all produce a concept of ‘firing’ which exists nowhere else on film.13

The Cossack’s sabre slash in The Battleship Potemkin already pointed in this direction, but that could be explained by a technique of elision, of less intended to produce more (like Mallarmé’s ‘paint not the thing but the effect it produces’), or of a mental image being prompted.14

- Paying attention to those instances of transition where the basic unities diverge and thus make possible recognition of the intervals which perception normally effaces and mechanical succession hides. Dziga Vertov wrote in his first manifesto ‘We. A Version of a Manifesto’ that ‘intervals (transitions from one movement to the next) and not movements themselves constitute the material (elements of the art of movement)’.15 But it is only in ‘Stuttgart’ that Eisenstein refers to intervals and gives them a place in the dialectic of film (‘the place of the “explosion” is that of the concept’, he writes).

- Regarding the intertitle as having a shot ‘value’ (in Saussure’s terminology).16

These four points qualify Eisenstein’s hostility towards the retinal (as attacked by Duchamp also) and shed considerable light on his conception of an intellectual cinema whose later elaborations would tend in directions which remained secondary in ‘Stuttgart’.17

Two circumstances can perhaps explain his taking up a position on this occasion which insists on a material definition of the medium and on the ‘stripping bare’ of the process. On the one hand, Eisenstein was here addressing members of the international avant-garde, and especially proponents of the ‘pure cinema’ whom he had previously lampooned in ‘Béla Forgets the Scissors’, but would now be depending upon during his European tour, both at La Sarraz and in Paris.18 On the other hand, he had also recently signed the founding manifesto of the last Constructivist group to appear in that decade, the ‘October’ group (1928–31), in which he and Esfir Shub were the only film-makers alongside the Vesnin brothers, Gan, Rodchenko, Klutsis, Ginzburg et al.19 With its aim of giving form (oformlenie) to everyday life (byt), this group proposed a new design approach in all fields from architecture to the manufacture of utensils, and called for the dissolution of artistic institutions. His definition of art must therefore avoid the pitfalls of both the right (RAPP, vulgar naturalism) and the left (Novyi Lef, the ‘fetishism of the material’). And finally, after the publication of Malevich’s only two texts on cinema in 1925, Eisenstein could not but want to respond to the fundamental charge which the ‘Pope’ of Suprematism had levelled against both Vertov and himself: namely of having brought a new technology to the aid of perpetuating the old exhausted tradition of easel painting, even of resurrecting the ‘Wanderers’!20

At a time when, according to Marie Seton, he freely admitted to feeling constrained within cinema (‘too primitive a medium for me’, he had said to Hans Richter), and when he was working on projects like Das Kapital and The Glass House with an ambition which was without equal in the filmmaking of the period, everything would have encouraged him to believe that he was in fact going beyond cinema, as Malevich had transcended painting, forsaking the ‘shaggy brush’ for the ‘sharp-pointed pen’.21

At any rate, this lecture cannot easily be accommodated within a unitary, continuous view of Eisenstein’s thought, especially in view of the reworking which it undergoes in ‘Montage’. The four points already noted show that it has very special epistemological implications which must now be explored further.

It belongs, as we have seen, to a tradition of enquiry into the nature of cinema inaugurated by Shklovsky, which starts from the medium’s essential discontinuity. Also apparent is the influence of those Constructivist designers and photo-montageurs who worked only with ‘found’ images and ‘ready-made’ objects, giving these meaning through their reuse in constructions—an approach which the theory of attractions formalised for the cinema. Note that this position excludes, first, any problematic of the referent (either the partial or total image of the real); and second, any belief in the prior determination of the work by its material, which is understood as inert (nature as passivity). It operates in terms of the Suprematist challenge to create non-figurative images in the cinema.

The examples of non-diegetic, purely filmic or zaum construction in October reveal how much Eisenstein was influenced by such European avant-garde films as he had been able to see—particularly by Ballet mécanique and Entr’acte—and also how his project for a ‘de-anecdotalised’ cinema was prompted by the ‘film without a story’ of which Shklovsky had spoken.22

In this respect, the discovery announced at Oxford by Yuri Tsivian of an editing plan or script of October which amounts to a first version of the film is highly revealing.23 Naum Kleiman has already analysed the ‘interior monologue’ that leads Vakulinchuk to shout ‘Brothers!’ in The Battleship Potemkin.24 Here the filmic phrase that serves a similar function for the Bolshevik sailor in the Tsarina’s bedroom sequence is constructed out of the debris of a narrative, by compressing and reordering its elements. Between the metaphors of the ‘genital eggs’ at the heart of an episode which is relatively coherent in narrative terms and the filmic phrase which deconstructs the political and religious statues of the ‘holy’ royal family to produce the concept of ‘sterility’, there appears a space which is perhaps that of Symbolism. And it is precisely this that stimulates what we may term, following Lacan, the Eisensteinian ‘imaginary’, to the level of construction which takes it into the ‘symbolic’.25 The reduction of the content to objects which are articulated according to a logic of conflict-deconstruction (the ‘polonaise of the gods’ and the sailor’s monologue) amounts to a kind of iconic purification, while those metaphoric sequences —like the raising of the bridges in the first part of the film—effectively dam up meaning: they emphasise without explaining.26

It is undeniable that Eisenstein’s thought and practice alternated throughout the 1920s between two positions and that the ‘shift’ identified by David Bordwell was less a matter of actual transition (around 1930) than a continuing ambivalence.27 We have already seen how an identical or similar phrase may function differently in the contemporary texts ‘Stuttgart’ and ‘Beyond the Shot’. Now it is time to identify the source of this contradiction—obviously not something that Eisenstein himself recognised —which I believe lies in the opposition between the theory of ‘attractions’—as decisive a discovery for cinema as that of collage for painting—and the theory of pars pro toto. Depending on whether he was citing a phenomenon to analyse a piece of film or vice versa, Eisenstein could take either point of view. Pars pro toto presupposes a unity of the whole, drawing on the Hegelian notion of difference or otherness as only an aspect of the totality which is anticipated in each of its parts, while attraction implies heterogeneity. ‘Stuttgart’ marked the culmination of Eisenstein’s ‘attractions’ tendency and, although it remained unpublished at the time, he referred to it in a letter to Bryher and MacPherson as ‘one of the most serious and basic in what I think about cinema’.28 Returning to this text to integrate it into Montage, he ‘hid’ it beneath the now dominant theories of pars pro toto and obraz.

The second chapter of Montage deals with the base phenomena of cinema, movement and photography, and here he wrote of ‘a series of still photographs representing different phases of one and the same movement’, which are termed ‘photograms’ (kadriki, or ‘little frames’). ‘Stuttgart’, it will be recalled, only spoke of ‘stills’ which enabled objects to be tackled, while here they have become the ‘phases’ of a movement. This is why, later, the distinction between izobrazhenie (representation) and obraz (total image) can be applied to the base phenomenon: the photograms are representations (inessential though visible), while movement is the obraz, the essential image (although ‘mental’ rather than visible). Representations will not occupy much space because they fuse (a term which had previously been spurned) in the animated image. Hence Eisenstein’s hostility towards Futurism, at least as exemplified by Balla, to whom he again attributed an imaginary ‘man with eight legs’ (sometimes six), which ‘gives only an impression of movement: this purely logical and mental game can only “lay bare the process” and thus ruin the “delicate deceit” which could have, with greater subtlety, created illusion.’29 Hence also the now major interest—it was still secondary in ‘Stuttgart’—in the painting of Tintoretto, in Daumier’s drawings and in Serov, all of whom he believes inscribe movement in their forms without destroying its integrity.30

Painting and literature (a passage from Tolstoy) as antecedents serve to relativise the novelty of instantaneous photography and of cinema: ‘mankind did not have to wait for the invention of the camera in order to seize a frozen moment from a dynamic process.’31

This reaffirmation of unity and continuity can be linked with the debate which Shklovsky began in Literature and Cinema.32 Somewhat strangely, Shklovsky took up Bergson’s views on movement, on the ‘vital impulse’ (élan vital) and the error of discontinuity that human consciousness commits when it dissects and freezes the movement of life. In Creative Evolution (1907) Bergson referred to ‘the cinematographic mechanism of thought and the mechanistic illusion’, in order to condemn this kind of thought for its inability to enter the flow or flux.33 He accused it of taking ‘snapshots’ and of placing itself outside things so as to recreate them artificially, instead of merging with their inner development.

‘The world of art is the world of continuity’, according to Shklovsky; so if ‘cinema is the offspring of the discontinuous world’, it cannot belong to art and human ingenuity has created in its own image a new non-intuitive world.34

It was certainly the mechanical, the Urphänomenon des Films, which encouraged Shklovsky to deduce from this characteristic of cinema that it could not deal with pure movement, but only with movement-as-sign or movement-as-act (Bergson contrasted ‘action’ with ‘act’ and ‘duration’ with the ‘moment’). Shklovsky’s position was in fact rather ambiguous and he did not debate any of Bergson’s assertions (which Gaston Bachelard would do in his L’Intuition de l’instant of 1932). He took from Bergson however the assurance that cinema could not possibly claim to ‘capture’ real life when he returned to the ‘base phenomenon’ in 1925 to condemn the Cine-Eyes. ‘Cinema is the most abstract of the arts’, he claimed in opposition to Vertov’s factualism; and in this respect, Shklovsky remained always the most willing to ‘hear’ Eisenstein’s ideas.35

Eisenstein’s own position in relation to ‘Bergsonism’, both overtly and latently, was rather different, since he actually embraced all the negative points raised by the philosopher in respect of cinema or ‘cinematographic’ thought. Instead of denying the original sin of cinema, he wanted to display it: hence Kerensky’s ‘eternal’ ascent of the same staircase. In his otherwise straightforward critique of October, Adrian Piotrovsky rather curiously qualifies this as a ‘metaphor’.36 But it is no such thing! We have here a proposition on the nature of film which seeks to dispel both the diegetic illusion of a Kerensky rising to full power and the purely optical illusion of a continuous rising movement, reinstating instead the ‘lived’ experience of duration. The staircase, by virtue of its regular divisions, equidistant steps and unidirectionality, offers a kind of analogue of the film strip, with its material base and structure of successive photograms. Acceptance of the mechanical character of the phi-effect and recognition of the intervals between frames and of the resulting discontinuity of movement, amounts to a ‘stripping bare’ of the process (indeed of ‘the bride’ by ‘her bachelors’).37 This sequence has been insufficiently studied in relation to Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase or Léger’s washerwoman, who climbs the same staircase nine times in Ballet mécanique and thus brings cinema back to what Eisenstein regarded as its true forerunner, namely the circular discs of Plateau’s ‘Phénakistoscope’ and W.G.Horner’s ‘Zoëtrope’.38

For Bergson the interval was a neutral moment wherein is created an intermediate image derived from what came before and anticipating the next in line. In theorising the relationship between one photogram and another, Eisenstein was helped out of his impasse by the principle of the ‘stop’ (Ausschnitt) which he found in Tynyanov’s The Problem of Verse Language, where the unity was termed Abschnitt, referring to a site of dynamisation, a movement not additional but multiplying.39 Indeed movement in cinema is ‘some kind of cut’ + abstract time (of the apparatus) and is thus a ‘false movement’: Kerensky and his staircase exemplify this in relation to the illusory freedom to film movement. But, as soon as relationships are constructed which take account of the space between frames, the way out of the blind alley becomes clear. Yet Eisenstein distanced himself as much from any thought about the reproduction of movement as from Bergson’s inner intuition: it is externality that is needed in respect of the object. The object, nature, is inert and passive (being-there) and it must be dynamised from outside (by an initiative conscious of its goal).

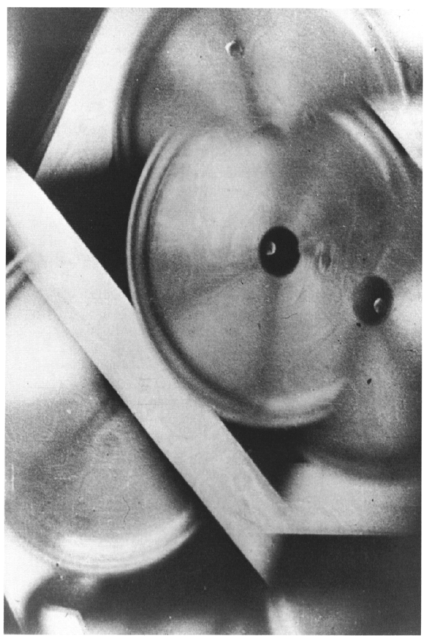

Finally, we may wonder what posterity has made of Eisenstein’s sketch for a theory of the photogram. At the end of the 1920s, Charles Dekeukeleire carried this idea to its most extreme conclusion in his astonishing work, especially the film Impatience (Belgium, 1928).40 This leaves to the spectator’s imagination whether or not a ‘story’ is constituted from four series of apparently diverse elements which are never correlated within the image, other than by juxtaposition and hence superimposition. The elements are a motorcycle, a woman who is sometimes naked and elsewhere dressed in leather, landscape and abstract imagery. These could be brought together intellectually by the sentence ‘A woman rides a motorcycle through the countryside’, but this would be absurdly reductive. The film’s movement is mostly produced by filmic means, involving collisions between frames, camera movements and very rapid cross-cutting.

Today, apart from such frame-based work as that of Sharits (based on blinking) or Kubelka (extreme fragmentation), mention should also be made of Werner Nekes’s highly systematic work.41 Nekes’s theoretical and practical enquiry into what lies ‘between the pictures’ has retraced, in more radical fashion, some of Eisenstein’s formative experiences.42 In Jüm-Jüm, he created a woman swinging—a recurrent image in nineteenth-century optical toys and one also placed at the beginning of Ballet mécanique, in negative, by Léger—entirely by means of discrete single frames. And he has even realised the dream briefly entertained by Eisenstein of filming Joyce's Ulysses.

Translated from the French by Ian Christie