By the 1990s, women accounted for more than half of all legal immigrants, shifting away from the male-dominated immigration of the past. Contemporary immigrants tended to be younger (ages fifteen to thirty-four) than the native population in the United States and more likely to be married than divorced. The 1990s also experienced a heavy influx of Hispanic and Asian immigrants, which hit a peak at the end of the decade. In 1990, for instance, more than 550,000 Vietnamese family members were settled in the United States. By 2000, that number was nearly nine hundred thousand. Mexican American family members were even more prevalent. According to the Pew Hispanic Center, legal Mexican Americans were 2.2 million in 1980, 4.3 million in 1990, and 7.9 million in 2000. Factor in another twelve million illegal immigrants, of which 80 percent are thought to be Mexican, and that brings the total Mexican population in the United States to roughly seventeen million people, or nearly 20 percent of the country of Mexico.

KEY HISTORIC EVENTS

MIGRATION FLOWS

Total legal US immigration in 1990s: 9.8 million

Top ten emigration countries in this decade: Mexico (2,757,418), Philippines (534,338), Russia (433,427), Dominican Republic (359,818), India (352,528), China (342,058), Vietnam (275,379), El Salvador (273,017), Canada and Newfoundland (194,788), Korea (179,770)

(See appendix for the complete list of countries.)

FAMOUS IMMIGRANTS

Immigrants who came to America in this decade, and who would later become famous, include:

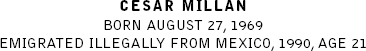

Cesar Millan, Mexico, 1990, dog trainer

Pamela Anderson, Canada, 1990, model/actress

Sergei Fedorov, Soviet Union, 1990, hockey player (defected)

Milena “Mila” Kunis, Ukraine, 1991, actress

Glen Hansard, Ireland, 1991, singer/songwriter (movie Once)

Anna Kournikova, Soviet Union, 1991, tennis player

Maria Sharapova, Russia, 1994, tennis champion

Ryan Gosling, Canada, 1996, actor

Xavier Malisse, Belgium, 1998, tennis player

Byung-Hyun Kim, South Korea, 1999, baseball pitcher

His story is remarkable. It personifies the American Dream and the immigrant quest for freedom. He grew up on his grandfather's farm in Culiacán, Sinaloa, Mexico. When he was twenty-one, with images of Disneyland and Rin Tin Tin dancing in his head, he said goodbye to his family and headed north to America alone in his goal to become the “best dog trainer in the world.” Though he spoke no English and had only $100 in his pocket—the family savings, given to him by his father—he crossed the border illegally at Tijuana with the help of a smuggler called a “coyote.” He went on to found the Dog Psychology Center in Los Angeles and became known for rehabilitating aggressive dogs. Today he is internationally known as “The Dog Whisperer” from his hit television show, which first aired in 2004 and is now broadcast in more than eighty countries worldwide. “Mexico is my mother nation, but America is my father nation because America gave me the direction that I should take,” he said, having received his citizenship in 2009. “So how do I feel about finally being part of a country that I'm in love with? I have a great amount of appreciation because my children were born here, and I met my wife here, and the world got to know me here. It was hard to touch my dreams, but this is the place in the world where dreams come true.”

Growing up on my grandfather's farm in Mexico was a traditional, physical way of growing up for any child. We didn't spend a lot of time in the city, and being around trees and going to the river and surrounded by chickens and cows was the norm. My grandfather never panicked. He never got angry. He was the epitome of calmness—calm assertiveness.

My mom was born on a different ranch, and my dad was born in Espadino. And normally the woman follows the man in my country, and Mom is just the sweetest, most supportive woman on the planet, and my dad is a very driven individual with big goals to make it outside the ranch. And he did. He did it for himself as much as he wanted to do, and so I grew up with a combination of assertive people [who had much] love.

Growing up on the farm, I learned that the best school in the world is Mother Nature and to work with what you have: honor the earth, honor animals. My grandfather always said, “Never work against Mother Nature,” and then I came to America and found out about a guy named Gandhi who said pretty much the same thing in different words. You know, I have my own Gandhi. My grandfather was my hero.

I was “El Perrero” [“The Dog Boy”]. That's a negative label that they give to people who are around certain animals, and in this case, dogs. When I was growing up, dogs for us were like family members—friends and helpers and everything…. We moved to Mazatlan about the time I needed to go to kindergarten. We started going five days to the city and then came back on the weekend. We had to go to Mazatlan because there were no schools near the ranch.

Then at age thirteen, I was going to a judo competition and I told my mom I wanted to be the best dog trainer in the world, and she said “Of course you can. You can do whatever you want.” So from that point on I declared that this is what I wanted to be in life. I wanted to be the best because there were trainers who started coming to Mazatlan, and I asked why those dogs do what they do, and that's when they explained to me about people who train dogs. Being a veterinarian was another choice…and then the reruns of Lassie and Rin Tin Tin started happening in Mexico. So I had adoration for America because Disneyland and Hollywood were here, and that's where Lassie and Rin Tin Tin were. [He laughs.] So I was already in love with this country….

The day I left for America was December 23, 1990. Something in me said, “I want to go to America.” I told my mom, and she said, “Where are you going?”

I said, “I'm going to America.”

“But the day after tomorrow is Christmas.”

“I know, but I have to go.”

So she called my dad, and my dad came and gave me the family savings, which was one hundred dollars. And with that money and my savings I paid for my bus ticket, and then I tried to save the hundred dollars so I could eat once I crossed the border. But I finished using that money to pay the coyote guy, so when I finally was able to jump [the border] I didn't have any money. I was trying to cross from Tijuana. The coyote charged me one hundred dollars. For me, that was God sending me somebody to tell me to cross because I was already trying for two weeks and no luck. I was trying to cross on my own because I was trying to save the money. I was trying to imitate how they do it, but since I didn't know the roads, I didn't know when the immigration officers changed. I didn't know anything about the whole system, and those people master it.

I spent Christmas and New Year's on the border because I crossed two weeks later. I didn't know anybody. Some people were having a good time, but when you're on the border, that's a whole different world. It's like if you go to Tijuana and you go to the places where people celebrate, where the Americans go and drink, they don't know we're crossing. They have no idea, and they don't care! They're just buying dollar stuff, beers for a dollar, and it doesn't matter what day it is, or that it's New Year's, but for the immigrant that's not on your calendar, it has nothing to do with your life. Your life is to find a way to cross the border.

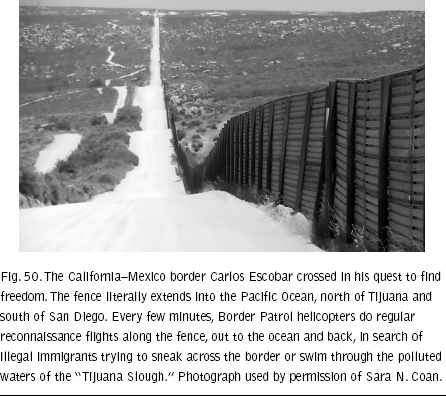

The border fence goes into the ocean at Tijuana, and I tried that, but it's just so hard. I didn't see a realistic way because you're sinking in the sand! And also where am I going to put my boots? You know you've got to carry the boots and it's not like we're crossing the Rio Bravo where you put your clothes over your head. I think the ocean is a little more risky, and normally people do the ocean at nighttime because daytime it's open! It's like, “Here I am!”

No, you look for the bushes; you look for areas where you can hide. It's the hunters and the rabbit. Also, at the ocean if they catch you, it takes longer for them to release you. But if they catch you close to the border [inland], they throw you out right away. I mean, I tried everything.

During the two weeks, I walked the entire border there. I saw people being dragged by the current because at that time it was raining a lot in Tijuana, so you could see people being taken away by the current of the water, especially the elderly people, pregnant people, children. It's really sad. It's just a sad story. It's a journey. It's like climbing Mount Everest. It was not a river—there were just areas because it was raining so much that it created canals. And then the coyotes—I guess this was their path in the past, and it was muddy and rainy, and this current just took these people. I don't know where it took them. And I walked the border fence; you can absolutely do it in two weeks, because you're not thinking, you're in survival mode, and your adrenaline is so high you're not thinking. What you're really thinking is worthless.

To survive you sweep floors, you ask for food, they see you're dirty. Some people give you tacos, some people say no, but you can survive because your adrenaline is feeding you, and somehow your body conserves whatever you eat. I ate tortillas. I ate whatever people gave me because I wanted to save my hundred dollars. I slept in the street. The street was my house. [He pauses.] You don't know how America looks. You can't even visualize it—all you know is “I have to cross.” It's a very simple concept. In my case I didn't know the territory, so once I go through this hole at the bottom of the fence, where do I go? Do I run in a straight line? Where do you go? I just had no clue.

I wasn't scared. Everybody asks me, “Did you ever have fear?” But I never had fear. It's just something that was instilled in me since I was little. I'm not afraid of dying. I'm not afraid of anything—what's the point? I have natural fear of fire or tsunamis or things like that. That's natural fear, but psychological fear? When you're little and they send you in the middle of the night to go and find the donkey, you face a lot of fear! [He laughs.] And so I was blessed to be with two people who were not afraid of anything—and they're good people, great people actually, my father and my grandfather….

The coyote found me. I was at the border because that was my job: to jump the border. I tried early in the morning; I tried in the afternoons, midnight. Then one day this guy came and said, “Do you want to cross the border?” And I said, “Yeah.” And that's when he asked for one hundred dollars, and I thought, OK, that's kind of weird. It was just him and I. That's why I felt like this was divine, his [God's] intervention, because this guy came from nowhere and he was filthy dirty. I mean, I grew up to learn not to trust people like this, but inside of me, I felt like I could trust him. It was an internal feeling that happened, you know?

We started crossing at seven p.m. I went to a place where this lady had a little coffee shop, a very humble coffee shop, and she sold gum, which is pretty much what keeps you awake: coffee and gum. There was a hole right behind her, and it was like she was guarding this hole. But this coyote knew the way…. He knew how to go through the tunnel under the freeway, which was a very scary moment for me:…we run, we run against traffic. You can see the cars, they're beeping at you—beep, beep—and then you've got to cross four lines [of traffic] and it feels like somebody's going to hit you—and I'm in boots, I'm wet, I'm full of mud, I'm a wetback. I am really wet!

After we crossed, the coyote brought me to a gas station and across the street from the gas station was the Border Patrol [headquarters] and I thought, “Oh my God, he brought me to the Border Patrol! He lied to me!”

No, what he did was he got me a taxi, which he paid for, so that it could take me away from there to San Diego downtown. I mean, this guy was an angel! He charged me one hundred dollars, maybe he made eighty dollars, and it took us hours to cross the border. Coyotes are not exactly known as humanitarians. They're just paying attention to how much money they're going to make.

When I got across, I celebrated like never before. I was alone. I celebrated the Mexican way—you know, we do the whole scream! I had no money because I gave it to the coyote, so I couldn't even buy a drink or anything. So what happened was I found a place under the freeway where I could go to sleep, and I slept for a whole day. But you don't sleep because you feel like you have to be on alert. So you sleep for two or three hours at a time because you're afraid people will take things from you while you sleep. They can kidnap you; so many bad things can happen.

I mean, I know I didn't do this on my own. [He chuckles.] My mom and God and my father praying were part of it. I am a very faithful human being. I am a man of instinct and a man of faith; that's what I came to America with. But that was my lowest, you know? I didn't bring any clothes, but I took that instinct and faith. And I prayed every day. I never stopped, and I never will! You know, when you grow up in a third world country, your instinct and your faith keep you alive. It's not your intelligence, and it's not your emotions because for the most part men can't cry so you learn to numb your emotions. You learn not to speak about emotions or to not show emotions, but instead rely on your instinct for survival and faith and hope that one day things will change….

I don't see life as hard. I lived the hard part of life already growing up in a third world country where you have to walk for water, you know? I am so constant to challenge. I'm so constant to believe that things will get better and so you can go through challenge, suffering, and at the end you're going to achieve what you're looking for. There's just no other way around. The storm doesn't last forever. So that mentality keeps you alive; it keeps you hopeful and allows you to not lose your patience because one of the things that happens is that people lose their patience and then they go back or they give up or they start drinking, and I can't give up. I never did.

After I woke up [under the freeway], I started looking around. I was in San Diego, so I didn't know anything about San Diego. I didn't have any need to stay in San Diego. My goal was to get to Disneyland or Hollywood because that's where Rin Tin Tin was, where Lassie was. I have to find the castle, the Disneyland castle, because every time I saw a Disney® show I saw the castle, and that's where Disneyland is. [He pauses.] I didn't know anybody here. [He laughs.] I was so naïve to think that Rin Tin Tin was going to be there, but that's what Hollywood and Disneyland sell you. As a kid in Mexico, I would watch Rin Tin Tin and Lassie on TV, and I thought, “I've got to meet their trainer. Those people are going to teach me how to train dogs….”

In San Diego, I started walking around and learning the culture of America. I learned the sentence, “Do you have application for work?” That was my first sentence. And then eventually I walked by this grooming place, and I said this sentence to these ladies, who gave me the opportunity to work for them, and that's when I started showing that I can work with aggressive [dog] cases, and that day I made sixty dollars! In Mexico it was a dollar a day. I went to 7-Eleven, and with ninety-nine cents I bought two hot dogs, and then I saved $1.69 to buy a Big Gulp™ so I could get the free refill—so you can live in America back then on a dollar a day.

I worked at a grooming place in Chula Vista [a suburb southeast of San Diego]. Two very nice Caucasian ladies gave me the opportunity to work for them, since I didn't speak English. They were elderly ladies when I met them, and they were hippie-like. They found out I was living in the streets, so they gave me the keys. So I slept in the grooming salon in the back, and then when I saved $1,000, I said, “I have to go.” It was not my goal to stay in San Diego. My goal was to get to LA. I never saw them again. You just move forward. When you're an immigrant, you're just moving forward. I wanted to be the best dog trainer in the world; that was very clear in my mind. But I had saved $1,000, so the first thing I did was I went out and bought my first pair of Original Levi's®! [He laughs.]

I took a Greyhound® bus to LA, and I left in the middle of the night because there's another border you have to go through near San Diego and then you learn that on a certain day, immigration people are not checking, they're not stopping buses. I arrived into downtown LA, and Skid Row was right there and I got to experience the first homeless people I'd ever seen. They were on drugs, and I was not around people who were doing drugs or homeless, so that was a shocking experience for me. I was not afraid of anybody. I just walked toward downtown LA, and I saw the buildings, and I said, “Well, you know, that's what downtown is; that's where the big buildings are,” so I walk toward there, and I found a place where I could sleep, and the next day I looked through the Yellow Pages: “Dog Training Facilities.”

I was hired by one in Gardena [a suburb southwest of Los Angeles]. I became the kennel boy. I learned how to take care of dogs and fed them. After I went to work at the dog training facility, I stopped looking for Lassie and Rin Tin Tin. [He pauses.] After my kids were born, I took them to Disneyland, but by then I wasn't looking for that. By that time, I became knowledgeable, and by then my wife, Ilusión, told me Disneyland is not where they train dogs. So that was a big disappointment.

I created a reputation of being a guy who can work with aggressive dog cases, and then I met a guy named Jay Reel, and he offered me a job as a carwash guy. I worked with his golden retrievers. I was not very happy working in the kennel. I worked sixteen hours a day, seven days a week. I worked there for almost a year. But I met good people; I met Jay, and he said, “You don't look too happy. I'll give you a job; it's not about dogs, but I can bring you the dogs of my friend and you can train them for him. You're good.”

So I start washing cars. At the same time, I was training dogs: teaching them to carry the bucket, carry the towel, bring me the water hose. They were my helpers, you know? And then he taught me about discipline in the American culture and about time. Because when you live in Mexico and you say you're coming, you come thirty or forty minutes later. So he taught me about being more disciplined with time. He not only let me work for him, he also took me to get my driver's license. He gave me a car to drive for free. We're still very good friends. By this time, I had gotten married and had a child. And then one day, he went to Lake Havasu, and before he left, he said, “By the way, you're fired!”

I said, “Why?” [He laughs incredulously.] “Why are you firing me?”

“Because you're ready to do it on your own—I'm certain.”

It's like: “What are you talking about? I have a child. I'm married….”

“No, no, you're ready.”

And it was “Bye-bye.” [He laughs incredulously again.] Just like that.

I was a good car washer, but at the same time, he knew that my future was with the dogs, and he saw something in me, and he said, “No, you're ready to go out on your own. You just have to go for it!” One thing, though: he still let me drive the car, and without the car I couldn't go and pick up dogs. So he said, “Keep the car. Just make sure to take care of it, and, you know, call me.”

I was thinking, “Oh my God, what am I going to tell Ilusión?” I just got fired. I can live on one dollar a day, but when you have a child and a wife, one dollar a day is not gonna make it. And then the rent. After I stopped being so chaotic about it, I just went back to my normal state and calmly, confidently figured, “I'll just go out there and tell people I need a job.” But what happened is I started walking more dogs. I became the Mexican guy who can walk a pack of dogs. And so I was walking thirty, forty dogs at ten dollars per dog—that's $300–400 a day, and so that was great.

That's when I found out that in America it's illegal to walk dogs off a leash. I mean, I had no clue. In Mexico, everybody walks dogs off the leash. Actually, it's more difficult to walk a dog on the leash. If my clients can't control the dog, I would say, “Take the leash off!” and the dog follows them. That's the nature of the dog. That's the nature of an animal, not to have a foreign object on his body. I mean, when I grew up I never saw a leash on a dog! So that was shocking to me, and that's when the whole thing about dog psychology versus dog training came to my awareness. “The Energetic Mind: The Revolutionary Style of Dog Training” I was calling it back then. I created business cards, passed them around, went to dog parks where people were training dogs. That's how I got to meet many African American dog trainers, and then we started networking, and they passed me clients who were not able to control or train their dogs….

The businessman in me came out later. I have a mind to work with people, and I have a mind to follow sometimes, but when the fundamentals don't match my core, I can't be part of that group, you know? It's just very difficult, and that's when I thought maybe I should open up my own business. I didn't know how. I didn't know what it entailed. I was totally clueless about business. What am I going to call myself? That's when I came up with “The Dog Psychology Center of Los Angeles.” America will not buy a title that says, “Common Sense for Dogs,” you know? And that's when I realized that a lot of people go to psychologists. And so, OK, Americans will buy a title if it has “psychology” in it. So then, I thought, how much is it going to cost? Many people around me said, “You're not a psychologist; you can't get that title.” So it was a little discouraging, but at the same time, I thought, it doesn't hurt to try! Everybody told me, “You can't jump the border,” right? So it's like the same metaphor.

I actually saved $300 because I thought it was going to be that expensive. Back then I had no money. I went to City Hall and applied for the name so I can have a license: the Dog Psychology Center. And it ended up costing me fifteen dollars. Just like that. Nobody owned the name, and you didn't have to be a psychologist to own a title like that. You can't call yourself a psychologist, but you can call places [psychology centers], so that was very empowering. I ended up with $285 back, which allowed me to buy Pampers® for André [his son] and formula and all that stuff. [He laughs.] That was a very proud day for me to have a title for my place, even though it was in South Central Los Angeles, a really beat-up place, a place where people said, “Nobody's going to come to South Central because people get killed in South Central.”

But months later, dogs from Beverly Hills started arriving in limousines to my place! [He laughs.] Having Nicolas Cage as a client, who lives in Bel Air, helps! One day his butler called me and said, “Mr. Cage would like to meet you.” And I didn't know who Mr. Cage was until he said, “Nicolas Cage.”

“OK, very good, I am available tomorrow. I would like to come and evaluate the situation….” So I did, and he had a pack of dogs. Most of the people, let's say 85 percent of my cases, are about aggression, especially when you have a powerful breed like a Doberman, Rottweiler, German Shepherd, or pit bull. He [Cage] had already called the other professionals, and there was one guy left and he's in South Central, so you might give him a try. [He laughs, then playfully.] “He's in South Central; he knows how to handle aggression. Don't you worry about it!” More than anything, you train the people. For the most part, their time is invested in other areas and dogs are more for affection purposes, so normally when I finish training the people, it helps.

Some early clients were Redman, who was really a hot commodity. He was a rapper and he helped me in the rap community, and Jade, in the hip-hop community. In the actor community, producers like Barry Josephson helped me, and Roman Phifer helped me in the NFL community, and someone in the NBA circle, and the billionaire circle—and so you've got all these amazing people who are successful, but they have trouble with their dogs or a lot of trouble with their dogs, and everybody has a circle, and once somebody lets you in, the networking begins. And to me, it's always about being truthful, having integrity, and that's how you create the loyalty of your clients….

I saw my mom again after I got my green card. I got the green card five years after I married Ilusión [1997], and I got my citizenship last year [2009]. My mom came here because she wanted to meet my son. You know, my mom never had a passport in her life, never flew on a plane, but she got a passport and a visa and she came. She came alone. And I remember we had like thirty minutes of letting it go. She's just pure love, and I understand sacrifice because of her. At that point, I hadn't seen her in eight years! I mean, she definitely raised a very strong human being. And she was proud of me….

Soon after that, I went back to Mexico for the first time since I came here. I went back and I ate everything. [He laughs.] No apprehension—I was going back home. I wanted to see my family; I wanted to see the ranch. We flew. We didn't go through Tijuana. To go through this border [at the airport] [sighs in relief] and have it [my passport] stamped was like [laughs heartily], “Wow! So you're saying I don't have to run?” [He laughs.] But I still see them [Border Patrol agents] in uniform and will get nervous even though I have papers in my hand, you know? It took a while, a few trips for me to get over that: that I don't have to run, I don't have to hide, I don't have to feel uncertain about the uniform. It's sort of a Pavlovian response; they trained me well! [He laughs heartily.] Now when I'm at the airport and security people see me, they bring me all the way to the front. I cut the line, and they say, “Will you help me with my dog?”

The TV show happened as the result of an interview I did in 2002 with the Los Angeles Times, and they followed me for three days. At the end, the reporter asked me, “What would you like to do next?” And I said, “I would love to have a TV show.” The newspaper story came out on a Saturday, and by Monday a whole bunch of producers were outside the warehouse in South Central Los Angeles—the very place where people said nobody's gonna come! [He laughs.] That's where the TV show was born: South Central Los Angeles.

So I said to the producers, “One of the things I want you to do is walk through the pack. And the pack is going to evaluate if I can work with you or not.” [He laughs.] “The pack will growl. The pack will walk away from some people. The pack will give them their back, and that means you can't work with me.” Well, one of the producers walked through, and the pack came to them, and we've been together ever since.

You can always count on the dogs. As I said, I'm a man of instincts and a man of faith. That's how I jumped the border: all those angels given to me by God—the divine intervention, the divine help. So gratitude is always how I begin each day. I begin with prayer, and I always pray around dogs because they always believe what you believe. Sometimes you can pray around people, but they don't believe what you believe, so they're blocking your prayer! But you can always count on the dogs because when the dogs are around me they're my anchor, so you just go into an automatic state of mind and you're not in conflict; you're just clear. And that's what I want to bring to people's lives: that when you are with a dog, conflict should not be in your being, and a life without conflict has joy, has happiness….

My number one hero is my grandfather, who taught me never to work against Mother Nature. But also Oprah because she is a true American Dream. She comes from a poor background, abused background. She knows how to deal with uncertainty and has the respect and loyalty of the American people. Even though she's a black woman in America, she pretty much rules the world. You're talking about somebody who has a really bad background and made the best out of it. She won against all the odds. That just shows you that the willpower of a human being has more importance than the lack of knowledge of a person.

The proudest moment for my dad—that “My son made it!”—was when I was invited to the White House in 2006 because he's a politician at heart. My dad works for the oldest political party in Mexico, so when I was invited to the White House, Mr. Bush was there, and I was right next to the king of Spain, and all these amazing people were in the front row a few feet away from Mr. Bush. But when I first arrived at the White House, everybody formed a line. But everybody has to be checked, so I went in front of the line passing all these important people and everybody's like, “Who's this guy?” And I heard a Secret [Service] agent say, “That's the Dog Whisperer. Don't you see the show?” That was an amazing experience. I gave Mr. Bush a “Pack Leader” hat and a “Pack Leader shirt,” and he sent me a letter thanking me.

I love that quote from Mr. Kennedy, “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” That is a true pack leader, you know? Because in the dog world, the pack leader is not there for himself. He's there for the pack, and so that quote of Mr. Kennedy is so animal-like, so instinctual-like because it's all about service. That's the state of the divine, and that's to be enlightened: that you want to help the world to get better in some shape or form, and that whatever your situation in life, the situation with everything is just your growth. The point is that you understand that things happen for a reason, and you find what the reason is, you act on it, and move on. You live in the moment, and you live calm-assertive, like my grandfather. He's no longer with us, but he would have given me the simplest solution for anything—and it would be like: “What? It's that simple?” Yeah! Life is simple. We make it complicated. It goes back to that. The human loves to complicate things. The intellectual loves to complicate things, and emotions sometimes get in the way of you seeing logical simplicity and really taking advice from anybody.

I'll tell you a story. One day I was in New York, and I was walking with my brother. We had finished a nice Italian dinner, and then I see this homeless person with dreadlocks, and he said, “Hey, you! You're the Dog Whisperer!” [He laughs.]

“How do you know?”

“I watch TV! You're really good!” [He laughs.]

And the first thing that came out of my mouth because he seemed so happy was, “So how do you stay so happy?”

And he said, “I go with the flow.”

The next day I get to meet a billionaire, and this guy owns cruise ships and casinos, and I said, “Sir, you seem very happy. How do you stay in that state?”

And he said, “I just go with the flow.” [He laughs heartily.] But going with the flow doesn't mean you let people push you around. That's not what they're saying. It's just that you don't fight things that are happening. You go with the energy. Like my grandfather always said, never go against Mother Nature.

He came to America alone. He came to embrace the American Dream that so many people talked about back home in his village in Mexico. Carlos was twenty-six years old when he left his wife, mother, and young son. He crossed the border illegally with the help of a coyote. Once across, he journeyed north to a small town outside Sonoma, where he got a job at a vineyard as a migrant worker earning eight dollars for a twelve-hour workday. He eventually learned English and got a better-paying job in a lumber mill, earning more in a month than he did in Mexico in a year. It took more than seven years before he was able to get his green card and bring his wife and son to America. Today, Carlos, at age forty, a devout Catholic, lives happily in northern California with his family. He recently became a US citizen, but his greatest pride is his son: “my papi, my Pedro,” he said. “Pedro is going to college now and working hard to make his dreams come true. He wants to be a lawyer and one day help other Mexicans who immigrate here.” He paused. “We miss Mexico sometimes,” he said, “but we are happy here, thank God. Will we return one day? Maybe. Just not today.”

My young son, Pedro, was five years old and he just kept crying. It was the day I left Mexico. I was about to begin my journey to America to find a new job and a better life. I had been a laborer, a construction worker, but the company I worked for closed and I couldn't find work. I desperately needed money to support my family. My mother ran a small bodega {store], but it didn't bring in much money. All four of us lived out back in an apartment. I wanted my son to have a good education and maybe one day go to college, which was never a possibility for me. I wanted to give him a good life. I did not want my boy to go through what I did; which is why I decided to come to the United States. When I was little, I sold food on the street so my family could eat. My father left us when I was little. I was an only child.…

One afternoon my wife, Rosalinda, and Pedro were at the bodega with my mother. Nobody said anything. They knew. I bent down to my boy, my papi: “I am going to America, but I'll be back soon, don't worry.” Pedro had tears in his eyes. “But why?” he asked and gave me a big hug. I felt like my heart was going to break. A short time later, a friend of mine came by with an old pickup truck and drove me about 250 miles to the north. I had cash with me and the name of a person, this coyote I was to meet there….

We met at a small run-down motel a few miles from the California border. The coyote had many people living in this horrible, dirty, tiny room waiting to cross. Many of them were there for weeks; some, months. He told us not to go outside until it was time to leave. He said it was for our safety, and he warned us. He said there were a lot of dealers, a lot of drugs, gangs, and people had been murdered, robbed, disappeared, and if we went outside there was nothing he could do to protect us; we were on our own. But some people didn't care, and they took a chance, even if it meant smoking a cigarette…. I stayed in that room for eight straight days, imagine! We slept on the floor. There were cockroaches everywhere. The toilet didn't work. I will never forget the smell. It was not something I can describe. There are no words for what it was like. As if that weren't enough, everyone was going crazy, so some people would sneak out at night.

I remember one young girl—she was so sweet, so pretty, dark hair. Maybe sixteen, seventeen—practically a child. Her name was Carlita. Me and some of the older ones in the group sort of looked after her like a parent. Well, one night Carlita went out for a cigarette. She had been gone quite a while, maybe a couple of hours, and we started getting worried. Then, later that night, we could hear screams, the voices of men. I moved to the door to go after her, to save her, but some of the others held me back. [He pauses, emotional.] I never saw her again….

We walked across the desert into Arizona. We traveled at night. It took three days to cross. We were sore, hungry, thirsty. At one point we didn't have a drink for nearly two days, but we just kept going, kept walking. We ran out of water because the coyote said not to carry too much with us because he said it would slow us down. Of course, he made sure there was enough water for him. He wouldn't share it either, the bastard! And a rich one, too! It cost me more than $3,000 to cross….

There were fourteen of us. There were lots of rattlesnakes, scorpions, heat, dust. And when it rained, lots of mud, so it was slow going. You had to be careful where you stepped. One bite from a snake or scorpion and you're gone like that [snapsfingers]. I could see the lights of the American Border Patrol off in the distance. The coyote told us that many like us did not make it, and there was no reason to doubt him. In fact, at one point, just off the trail in a ditch, I saw what looked like the entrails of something covered with black flies. Thousands of black flies. It could have been a cow or a dog,—I wasn't sure—until I saw what looked like a human skull and bones in the dirt. So apparently we were not the first to come this way and I remember thinking, “This loco. This is crazy. I wish I had never come.”

Once we made it across, we had to lie down in a van. The coyote's brother drove, and we finally got some water. It was a long drive, many hours to the north of San Francisco to work in the vineyards. We were known as the mojado, or the illegal ones….

When I arrived, my English was very poor but enough to get by. I wanted to go to school to learn, but I had to work all day, and they were long days. I did this so I could send money back home to Rosalinda and my mother. I would study English in the nighttime after work, and there were several others. It was a group of us: the workers, the mojado. We used to meet in the basement of a small mission church. It was sort of a like a Bible study group except we also learned English. A local woman who once lived in Mexico translated back and forth into Spanish. She taught us. She was a good woman. In her fifties. Her name was Zulma. She gave us books to read, but more importantly, she gave us hope. And then the years passed—and I learned and I worked, I prayed, I wrote letters. I sent money back home. This was my life for a very long time.

Many of the mojado—the ones in our church group, anyway—returned to Mexico. They were not happy because the life was too hard. We lived in shacks on the outer fringes of the vineyard fields. There was some electricity but no plumbing. No running water for showers. We had to go to a communal building for that. And the bedsprings were rusted and the mattresses filled with mold. One friend of mine got sick. He had no money for a doctor, much less medical insurance, and he said, “I do not want to die in California. I want to die in my country. I want to die in Mexico,” and he went home. For others, they never intended to stay anyway. Their plan was simple: come here, work, make the money, take it home, and hopefully take enough where you can set yourself up somehow. For the ones that stayed, like me, Zulma helped us get green cards….

It took me over seven years to raise the money to bring my Rosalinda and Pedro to America. By that time, my mother had passed. The last time I saw her was the day I left Mexico to come here. But the day I saw my wife and boy again, that was a day! My family was together again. Pedro had become a big boy now, almost thirteen years old, and Rosalinda looked like an angel. Beautiful. This was the greatest day of my life. [He pauses.] My next one will be when Pedro graduates college. He wants to go to law school. He said he wants to help others come here, the way he wishes someone had been there to help his padre.

She came to America to escape a bad marriage and start a new life. Her dream was to get an education, but her background went only as far as primary school. Relying on domestic jobs to support her, she passed her high school equivalency exam and finally, at age fifty, earned an associate's degree. That same year, 2007, she married her second husband, with whom now she lives happily in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. In 2009, she earned her bachelor's degree in English education and is working toward her master's to become a teacher. “I am very happy that I came to America,” she said. “I can honestly say that my life began at fifty when I graduated college.”

I left Trinidad because I was in a very bad marriage and I wanted out. The children were old enough where they could take care of themselves, and I thought it was time. I am from India; my grandparents are from India. My great-grandparents went to Trinidad as indentured laborers, and then my grandparents followed. My grandmother was born in India, but my mother was born in Trinidad. So we've had two or three generations of our family in Trinidad. So Trinidad is my home, not India.

I was married for twenty-five years. Yes, it was survival of the fittest. I have three children, three girls, but when I got married, he had two children that came to live with us, and they were the cause of the bad marriage. It was like I had no say and they had all the say in the marriage. They became the bosses. I felt like the slave. Indians are very obedient and humble, and they take care of their home and their family. I got married to someone who is not Indian. He was African: a black man from Trinidad, which was a no-no in my culture. So as far as my family was concerned, I was dead. I thought they would have softened up after a while, but they never did until I left for good.

So for twenty-five years, the relations with my family were bad. I mean, my mother, my sister, and I spoke to each other, but there was always a distance. It's only after they realized I had left him for good and filed for divorce that I felt welcomed back into the family. This happened when my mother was dying. I was already here [America] in 2002 when my mother got really sick, and I went home to see her. She was at home with my sister in Trinidad, and I think she died peacefully, knowing that I would not be going back to him.

What many people don't understand about a third world country: Once you get married, that's it. You have no other choice. So in my situation, I got married to someone who my family did not approve of. I had no education to find a job on my own. I had nobody to take care of my children in case I did get a job. I couldn't just leave them with anybody because I couldn't afford to pay a babysitter, and to get a good job, you have to have a good education. At that time I only had a primary school education.

I knew when I filed for divorce I would have to leave Trinidad. I filed over here [United States]…. His eldest daughter was like the main person in his life. She's a grown woman now. But I came here in 1998 to escape him. That's what I did.

A friend of mine had come to Trinidad for Carnival in February of ‘98, and I told her what was happening with me and that I wanted to get out, and she said, “OK, I'll help you.” She provided a place for me to stay in her apartment in Brooklyn. I came in April 1998 on a tourist visa. My eldest daughter was already over here in America, in Brooklyn. She came here before me in 1998 when she was nineteen on a holiday [tourist] visa, but later on she got a student visa. I found a job in Greenwich [Connecticut] as a live-in. I took care of two girls; taking them to school, getting up in the morning, packing their lunch, helping fix their dinner [and so on].

I worked there for five and a half months because I didn't want to overstay my visa. But I went back home, and within two weeks I was ready to leave. I couldn't stand him! I didn't want to leave because of the children, but I couldn't be around my husband at all. It was just too much! I didn't know what to do because I had left the two children in Trinidad. One was thirteen and one was eighteen. It was very difficult for me to leave them, especially the younger one. One was getting ready to go to university, and the other one was just into high school. When I told my husband I got a job [in America], he didn't say anything because I needed to pay the university fees. So that was my excuse, right?

And over the course of the next five years, that's what I did. I went back and forth. I had a ten-year tourist visa, but you have to go back every six months. So I would go to Trinidad and then come back to Connecticut to continue the job. I did that every two or three months because of the visa and because my mother was very sick and I didn't want to overstay my time here [in the United States]; then if something happened to her, I wouldn't be able to travel back. When I came back, although my husband and I lived in the same house, we didn't have much to say to each other. We slept in separate beds. I slept with the children. So it was under the same roof, but it was very far apart, and he was dating other people, also Indian women….

By 2002, my mother had died, I had filed for divorce, my children had grown, and my eldest daughter was here in Brooklyn. I always wanted to have an education, so I started my GED classes on Saturdays while I worked in Connecticut from Monday to Friday. In my culture, the girls are not pushed for an education. You're pushed, really, to take care of the house and your family, and that's it. You get a primary education, and that's it. You know how to read and write, but you have to cook, clean the house, learn to sew, and take care of the husband and your children. That's it.

I got my GED in 2002, then my associate's degree in liberal arts at Manhattan Community College. I went to Brooklyn College for another two years, and I got a bachelor's degree in 2009 in English education. Presently, I'm doing my master's at Brooklyn College to be a teacher. I would love to be a teacher, only there are no jobs for us right now. My eldest daughter is also at Brooklyn College with me, doing her bachelor's in business. My other daughters chose to stay in Trinidad. They didn't want to come here. One has a degree from a school of chartered accountants. The youngest one started her own business doing web design. My relationship with them is very good. They understand what I went through.

[She pauses.] I came to America to find a better life, but I realized that to have a good life here, you need to be educated or else you're stuck in a menial job. For me, an education is something I always wanted. It was like chasing an elusive dream. I graduated with my bachelor's degree when I was fifty-two years old! So you have to stay focused on your goals, and you cannot give in to the stumbling blocks that will come into your life. There are distractions, but you have to persevere. You have to. People say this country is the land flowing with milk and honey, but you don't see that milk and honey until you work for it. You cannot come to America and be lazy. If you come to someone's country, you have to be an asset to that country. That's what I believe. You have to have people respect you, and that is what I strive for….

I am very happy that I came to America. I can honestly say that my life began at fifty when I graduated college. I'm hoping by the time I graduate with my master's the economy will be better. My husband, thank God, can provide in the meantime. I do part-time babysitting to earn extra money, and I meet babysitters in Brooklyn Heights and I tell them, “You need to go to school!” And they look at me so funny. And I'm like, “No, you have to get an education! That is the key to success in this country.” And they look at me like, “What is wrong with this woman?” That's how I feel. I've always wanted to pursue an education, and my second husband is very supportive of this. I think that's what I love about him.

1990:

1990: