Census Bureau data show that immigrants who arrived in this decade were better educated than those who arrived in the 1990s. Likewise, children of immigrants were more financially successful than their parents and had more professional skills. The survey also points out that out of an estimated US population of 310 million people, more than 35 million were born outside this country. The bulk of immigrants since 2000 have come from Mexico and Latin America, but also from Asia and India, which have experienced a “brain drain” of sorts—particularly in science and technology—as many of their most intelligent and best-educated citizens have migrated to the United States and other Western nations to pursue better opportunities.

KEY HISTORIC EVENTS

MIGRATION FLOWS

Total legal US immigration in 2000s: 10.3 million

Top ten emigration countries in this decade: Mexico (1,706,993), China (599,914), India (597,032), Philippines (549,024), Russia (488,115), Vietnam (292,143), Dominican Republic (291,603), Cuba (274,028), El Salvador (252,526), Colombia (235,698)

(See appendix for the complete list of countries.)

FAMOUS IMMIGRANTS

Immigrants who came to America in this decade, and who would later become famous, include:

Catherine Zeta-Jones, Wales, 2000, actress

Steffi Graf, Germany, 2001, tennis champion

Mats Wilander, Sweden, 2001, tennis champion

Hideki Matsui, Japan, 2002, baseball player

Yao Ming, China, 2002, basketball player

Rachel McAdams, Canada, 2002, actress

Somdev Devvarman, India, 2005, tennis player

Rachel Weisz, England, 2006, actress

Sacha Baron Cohen, England, 2007, actor/comedian

Markéta Irglová, Czechoslovakia, 2010, singer/songwriter (movie Once)

Zeituni Onyango (“Aunty Zeituni”), Kenya, 2010, President Obama's half-aunt (deportation waived)

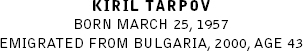

He is a music teacher and conductor from Plovdiv, Bulgaria's second-largest city. He came to America as part of a cultural exchange program and to give his adopted son, Angel, a better life. Like the Ellis Island—era immigrants before him, he worked and sent money back to his mother in Bulgaria until he was able to bring Angel, a gifted cellist, to America so that he could pursue a music education. They eventually settled in the Midwest. He remembers being new in America and working on Wall Street, a few blocks from the World Trade Center, when the 9/11 attack occurred. “I called to Bulgaria and I hear the voice of Angel, my son.” {His voice cracks.} “He doesn't know what happened, and I didn't tell him. He just wanted to hear my voice, and I wanted to hear his. And when I hear his voice, in this moment, I realized maybe our building is going to be the next one and I'm never going to see him again and I start crying and I closed the phone.”

I came to America to visit in 1999 as part of a Bulgarian group for a cultural exchange program. I came here with a regular work visa because at that time I was involved with the cultural exchange between Bulgaria and the United States. I was working with a music foundation in Bulgaria in cooperation with another foundation in New York. We had started this cultural exchange program in 1998, and we organized different seminars and workshops in Bulgaria, and here we worked in the American educational system—in the high schools and universities—with the idea of creating a Bulgarian-American Arts Festival. We would have concerts at the Bulgarian Embassy in New York….

When my visa expired, I had to return to Bulgaria. Then I received an invitation from the Bulgarian Eastern Orthodox Church based in New York to become their music conductor, and they offered me a work visa, which enabled me to continue my work in the cultural exchange program here, and on April 1, 2000, I was in the United States and have been here ever since.

I came here to continue my work in this cultural exchange program, but the other reasons were to have a future as a musician, and second, to give a chance to my adopted son because he has dark skin—his parents were Egyptian, and back in Bulgaria we have a lot of problems with people with dark skin color, and I soon realized it's going to cause a lot of problems for him—and for me to give him a chance at a better life. That's why when I had this opportunity from the church to come to the United States, I started thinking, why not become an immigrant? With a work visa, I could get a green card, maybe, and become a normal American….

I adopted my son in 1996 after I came back to Bulgaria because I wanted to have a child. With my ex-wife, we didn't have a child…. I asked all my friends to help me find a way to adopt a child, but because I was single; the advice was to have one child and see if it works. At the time, I was a music conductor with a new Bulgarian opera, and we had a big tour in Europe and then two weeks in the United States. It was my first time here. My first stop was in New York. I remember when I stepped down from the bus in the city after arriving at the airport, I thought, “This is my city; this is where I want to live.”

Then, one day, a friend of mine called me to go to an orphanage because they're going to move the kids from one facility to another and it's a good time to see the kids. They were around three to three and a half years old. This was in Plovdiv, my home city, which was the second-biggest city in Bulgaria after Sofia, the capital. So I went to this orphanage around lunchtime. They had just woken the kids from their afternoon nap for lunch, and I looked at them, and I saw one boy's big smile, and I just said, “This will be my son.” I called him Angel.

Later they introduced me to him. After that, I started to prepare the necessary documents, and there was the hearing for the adoption. But I wasn't able to be there in court because I had a performance in France between Bordeaux and Marseilles, and that's when I got a call from Bulgaria: “You're a father now!” We had a big party, and then I brought him home, and after that, we started our life together.

Life in Bulgaria in 1996 was hard because the Communists were in the government, and this was one of the terrible years. I had found a job as a music teacher from the teacher's union in one of the schools so I could raise my son. It was very difficult because at nighttime I went to support the people who were against the Communists, and during the day I had to teach the kids and I had to raise my son, and it was an unpleasant time. The pay was not good. To give you an idea, for my two-week tour in United States, I was paid thirty-six dollars per day as a conductor. This was like a whole year's salary for a teacher in Bulgaria—can you imagine? And I wasn't a regular teacher; I was a well-known music teacher. So money was one real motivation to come to United States.

After the adoption, I also realized Angel was very talented musically, and it was impossible to give him a future in Bulgaria. He started to play the cello when he was four and a half years old. I got him to a teacher for lessons, and I saw he had natural talent with a good ear.

When I came here in 2000, I left Angel with my mom. The Bulgarian church had given me a work visa, but they didn't give me any salary, so I had to find work to pay my expenses and to send back money to Bulgaria for Angel. So I started to work at a coffee shop on Wall Street in New York, and at this time I didn't speak any English. But I was working with the customers, and it's amazing how kind they were. They took their time to explain things to me, what things meant, like “bagel with cream cheese,” because I didn't know. Or what does it mean when they order “coffee with cream” or “[coffee with] skim milk,” for instance? When the customers had a break, they'd come down from their offices to the coffee shop. Some of them came just to help me and teach me, and that's how I started to learn English. That's why I respect and I love New Yorkers.

I was here when the 9/11 tragedy happened. We helped a lot of people with water and everything. There were people who lost consciousness. From the outside they came in or were brought in not breathing, and we helped them. That day, in the beginning, somebody said a plane crashed into one of the Twin Towers. At first I thought it was some spoiled kid without any license to fly who crashed into the tower, and then when the second plane crashed, everything started going so fast, and we realized what happened.

After the collapse of the first building, everybody started knocking on the windows of the building to let them in, but security had locked the doors. It was a huge lobby of an atrium building at 60 Wall Street. Upstairs were several big financial companies like J. P. Morgan. Everybody started knocking on the windows to come in, but the people on the inside started screaming, “Don't let them! Don't let them in!” I thought, “You can't keep these people outside! Let them in!” They were covered in dust and debris. We let them in, and we helped them wash their faces because they couldn't see anything, and we helped some to start breathing because they were choking, coughing from the dust. We gave them water to drink to clear their throats. A few minutes after that, I find the phone, and I called to Bulgaria because the coffee shop had international connections because the owner was Turkish. I called to Bulgaria, and I hear the voice of Angel, my son. [His voice cracks.] He doesn't know what happened, and I didn't tell him. He just wanted to hear my voice, and I wanted to hear his. And when I hear his voice, in this moment, I realized maybe our building is going to be the next one and I'm never going to see him again, and I start crying, and I closed the phone.

Then the second building collapsed, and they sent us to the basement, and everything down there was dark; we were below street level. Up until then, we didn't have a chance to think about what happened outside, and then I realized what kind of tragedy it was. Then security said, “Go out! Everybody out! Everybody out!” and around one p.m., security had us leave the building, and we walked. Everybody walked home.

Far removed from any border, the heartland of America is not necessarily thought of as a place filled with immigrants, but its face is changing. The push-pulls of immigration on a national level can be seen and felt in places like Marshalltown, Iowa. Originally from Illinois, Sister Christine is an immigrant of sorts, having spent fifteen years in Bolivia before returning to the United States. She came to Marshalltown in 1999 to become the director of the Hispanic Ministry Office. Since that time, she has watched the town transform from a sleepy Corn Belt community right out of the movie Field of Dreams to an immigrant hotbed where nearly a third of the population (and rising) are immigrants, primarily Hispanic. The American Dream may still be alive, but the voices being heard are increasingly Hispanic ones. Marshalltown's population of approximately twenty-six thousand has remained virtually unchanged since 1999; as the immigrants have come, many of them illegal, the locals have left. There is a huge black market for Social Security cards, driver's licenses, and the like.

Sixty-two years old and fluent in Spanish, Sister Christine is a trusted figure and advisor to the Hispanic community here, who have relied on her for everything from immigration help and advice to language interpreting to friendship and moral support. While poor English, illegal status, and fear of deportation keep some in the shadows, people like Feagan provide hope, as most immigrants here live in fear of ICE. Stealth undercover raids in 1996 and 2006 at the Swift meatpacking plant, a major employer, still resonate with residents, both legal and not. “I think it would be great if everybody wore sunglasses and the colors looked the same,” Feagan said. “I think a lot of it is not just an immigration issue—it's a race issue. I really do. Because when people talk about immigration, they talk about Mexicans.”

I've been in Marshalltown since September 1999. Since then I've seen a lot of changes: demographic changes, growth in the community and in our parish. When I first came, for example, there was one Spanish mass on Sunday in early afternoon. We now have a Saturday night mass and a Sunday morning mass, and the church is overflowing on Sunday. The parish has changed from being about 20 percent Hispanic when I came to about 65 percent Hispanic now. Most of the people come from Mexico. We have a few from Guatemala, some Salvadorans. Some people originally settled in California and then moved here. Some settled in Washington State and then came here. Some came from Nebraska. It's hard to tell among the Hispanics who's illegal or legal. They all look the same. [She laughs.]

Originally, the Hispanics who came here were mostly single men, and now a lot of them have brought their families up and applied for legal permanent residency. A lot of those legal permanent residents recently became citizens to speed up the process of bringing up family members because otherwise the wait time is years to bring family members from Mexico.

I'm the director of the Hispanic Ministry Office, and that's another thing that's changed. When I first came, a lot of people would ask us for help to get their telephone set up, or help them about paying a bill at a hospital, and so we would do a lot of interpreting and accompanying them on appointments. Now, if you go to the bank in town, there are Hispanic tellers, and if you go to the hospital, there are interpreters; just about any place you go now, you will find Spanish-speaking people. What I'm saying is there is an awareness that they [Hispanics] are here and so we need to serve them. Today the total population is about the same compared to ‘99, but it's changed demographically. As Hispanics have moved in, the Anglos have moved out.

I am the Hispanic minister at the church. People come here, to me, if they don't understand their rent bill, and we have a counselor that comes two days a week, so it's like an outreach office, and a lot of people come and say, “I need work. Do you know of anybody looking to hire for housecleaning, taking care of kids?” or whatever. In the office here we do a lot of work with immigration papers for when people are applying to bring up a relative, or they need to renew their green card, or they're applying for citizenship, or they need a permission letter that says one parent is going to go with the kids down to Mexico and they need the other parent to have a notarized letter giving permission. People will come in and they'll need a recommendation letter for immigration purposes that says this person or family are registered members of the parish. There's a lot of that kind of thing. And then there's a lot of people who just come in because they need somebody to talk to—just personal issues, things that are going on in their life.

I lived in Bolivia for fifteen years. I studied Spanish and French for ten years before I went down to Bolivia. I grew up in northwest Illinois. I came from a Catholic home, but I would say we weren't overly religious. When I came back, I was in Chicago on the South Side, working in a parish that was basically Mexican, and then a friend told me about an opening here for a Hispanic minister, and so I came. I did missionary work in Bolivia and was an immigrant there [laughs], so I have compassion.

In Marshalltown, there are problems for the undocumented people in that they're afraid all the time that they're going to be arrested by ICE, which stands for Immigration and Customs Enforcement. There are two arms of immigration. There is USCIS, which is United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, which would be like when you apply for something or you become a naturalized citizen. Then you have ICE…. That's your Border Patrol and what used to be INS. ICE has no office in Marshalltown. They come from Des Moines, which is about fifty miles away, and then wherever else, because I'm sure the agents who came in December of 2006 were from a lot of different places.

They're afraid of what's happening in other places in the country and that it's going to happen here. They're afraid that if they lose their job, how will they survive? Where will they go if the [social] climate is the same in other places? They're concerned for their kids' well-being. People here are happy to be here. They like Iowa. They like Marshalltown. We have a good school system. There's plenty of work. There's plenty of space, and I think that's what's attracted them. And it's peaceful. It's not crowded.

The major employer is the Swift meatpacking plant—hogs, pork. And then there's Lennox Industries, which makes heating and air conditioning units. But not too long ago Lennox laid off three hundred people because they sent part of their air conditioning production to Mexico. And then we have Fisher Controls, which is now part of Emerson, although very few Hispanics work there because it's a lot more specialized, so they don't have the training or educational background to be able to fit in. Fisher makes parts for boilers and heaters. Then we have the Iowa Veterans Home, and a lot of people work there in light housekeeping. We have the Meskwaki [Bingo] Casino [Hôtel] twenty miles away.…If they don't have good papers they can't work there. The same with the Iowa Veterans Home. And the Swift plant uses E-Verify® [an online system for checking employees' eligibility], so that's why during the 2006 raid Swift was not legally at fault for employing [those] who turned out to be illegal immigrants: because they had done “everything” they were “supposed” to do to make sure that people were documented.

By “good papers” I mean they [Hispanics] have their own Social Security number and are using their own name—that they are here legally. People [illegals, mainly] will see a roofing job going on, and they'll say, “Do you need work for the day?” and they work. Last year, there was a really bad hailstorm that happened in Eldora, which is about thirty-five miles from here, and so there was a lot of repair work, houses that needed to be re-sided and roofs that needed to be redone, so that gave work to a lot of people, plus cutting grass or landscaping or whatever they can do. In my experience, people are willing to do whatever.

Typically, an illegal immigrant will try to get a Social Security number that's not being used by anybody else. It might be a three-year-old child, a retired person, or maybe it's somebody who is not working who sold their Social Security number for a year. That can be done, too. So Social Security numbers are used to get a job. Have you ever seen an I-9 form? Because now everybody has to fill one out when they seek employment. You have to show proof of being in this country legally. And you can either show from List A your passport or from List B your Social Security card and driver's license or something else that has your picture on it.

If you're an illegal, it would be really hard to get a job at Swift, but many do, of course. First of all, it would be really hard if you're Hispanic because now we have another group who've moved into Marshalltown: the Burmese. They are here as refugees. And so a lot of those people are now working at the plant. They came within this past year. I don't know how many of them there are, but their English skills are very low, and it's hard to find interpreters. Obviously, it's not anywhere near the number of Hispanics, but because they're here as refugees, that means they're under “protected status,” so Swift prefers them.

A lot of people have come to Marshalltown because they knew somebody here. So now it's like the husband has brought up the wife and the kids [and] the brother has told his brother, “Hey, come on up. This is a really good place to be.” The interstate highways have made it easier. They have become a pipeline. We have Interstate 35, a pipeline from Texas. We have Interstate 80, which takes you over to Arizona; there's a lot of people that enter from Texas and Arizona. So the interstates have connected the dots and made places like Marshalltown more accessible. A lot of the Hispanics who were in California came here because work was getting scarce, the cost of living was too high, there's a lot of violence—so they're coming in many cases from California to Iowa. We've got a little group of people who were working in Washington State in the apple orchards and some from Nebraska and many directly up from Mexico, and a lot of them have come up legally. People hear the number twelve million and they think, “Oh my gosh, America is just crawling with these undocumented people,” but there are three hundred million who live in the country. So twelve million is a drop in the bucket, you know?

I see immigrants in Marshalltown from Bosnia, Croatia, both legal and illegal. A lot of them come in through Canada. Some of the Bosnians have refugee status, which makes them legal. Other immigrants here are Sudanese and Somalis who have refugee status. Then there are those from El Salvador who have TPS or Temporary Protected Status, which means they can get a work permit. There was a man who had a kidney transplant twelve years ago. He's a legal permanent resident from El Salvador. He was working at the Swift plant for a long time and then he had serious breathing problems and a heart problem, so the doctor sent a letter to the plant that said he can go back to work but he can't work in the “cold” area, the meatpacking part where they freeze the meat. Well, they kept him there in the cold areas, and he ended up in the hospital two more times, and the doctors finally said he can't go back to work. Period. His health was too fragile. So I went with him to Social Security to apply for disability, and they never give it to you the first time, but they gave it to him—that's how bad he was!

The pecking order in terms of demographics in Marshalltown is the Anglo or white US citizens, which is still the majority; next is the Hispanic population. We don't have many Bosnians around here. We used to have more Sudanese than we have now, but a lot of them have gone to Des Moines…. Before I came here in 1999, there was an influx of Laotians, and they were here for a while and then they left. After the 2006 raid, we had a huge influx of African Americans from Chicago and Minnesota. Some of them, I'm told, just came here to apply for government benefits because being a small state, it goes through a lot faster. They were here for a while and then left.

Then there's Juan and Elizabeth. They were badly affected by the raid. Juan worked at the Swift plant for several years. Then in December 2006, there was the big raid, and he was arrested and eventually deported. It happened December 12, which is the Feast of Guadalupe, which is extremely important to the Mexican people. And so at eight o'clock in the morning, I got a phone call at home from one of the people here at the office, who said that immigration had landed at Swift. People had gone into work for their normal shift at 6:30 a.m., and everything was in operation, and then at 8 a.m. everything shut down, and people were all herded into the cafeteria. Now, Swift employs about 2,200 people, so for the first shift, figure 1,100. So they herded everybody into the cafeteria, but people ran and they hid. And some people got chemical burns because they hid where they shouldn't have hidden; some people hid in freezers; some hid up on the roof.

I went over there. It was a cold, damp, nasty day, and there were people all lined up from the outside of the fences looking in, and, of course, there were ICE agents everywhere. Not even the city police, because supposedly the city police had not been informed this was going to happen. The day of the raid, ninety-five people were arrested from Marshalltown. They were illegal, and it was several days before anybody knew where they were because they were just taken and put in different places.

So Juan was arrested and deported. But he couldn't stay away from his family that was up here. He had a three-year-old daughter and a five-year-old son, so he came back and got a job working in Pella, Iowa, which is forty minutes from here. One morning, ICE came to their house, and he had already gone to work, and so they asked the wife, “Where is your husband?” and she said, “I don't know,” and they said, “You do know, and we want to talk to him.” But she insisted she didn't know, and they said, “Where are your papers?” and she doesn't have any papers, but she said, “I don't have to show you my papers because you didn't come looking for me,” which is correct. And they said, “We'll be back!”

So she was very afraid and hid for a few days with relatives, and then she got word that if her husband would turn himself in, ICE would not bring any charges against her because she, at one point in time, had used another Social Security number to work. And she had only worked for like three months, and that had been a long time ago.

Her husband eventually did turn himself in. He was brought to trial. He was sentenced to six months in prison in California, but he ended up being there almost two years! Then he was deported to Mexico, and he was given a “permanent bar,” which means he cannot come back to the United States legally, ever! And then, with his wife, ICE did not keep its promise, and they brought charges against her for using a fraudulent Social Security number. There were actually four charges brought against her, and they brought it down to two, but she was sentenced to six months in prison, and her first concern was her children: “If I run from ICE, if I hide, and they don't find me, I'll be safe, but I'll never be able to be free with my kids.”

So Elizabeth bit the bullet and did the six months in Danbury, Connecticut, and this is after paying a lot of money to a lawyer. I think the lawyer really let her down. Just let her down. It's a really sad story. So she was sentenced to six months in prison in Danbury, Connecticut. This is a woman who had never been on a plane before, and I helped set it up so that somebody would meet her in Chicago. She took the plane from here to Chicago, and we had to pay her airfare. ICE did not even pay for her to go to prison!

Supposedly Danbury was a good women's prison. I mean, we have immigrant prisoners in federal prisons in Iowa, Illinois, and Nebraska, but she was sent there, and she doesn't speak English. She had never been away from her kids. So I had somebody meet her in Chicago who got her on a plane to New York. Then I had some people meet her in New York who drove her to Danbury.

She did her six months' time, and everybody was hoping that afterward they would let her return to Iowa and work on a process to be able to stay because she had been here for many years. In the last month of her being there [Danbury] they told her that she would have to make a declaration in court, but she didn't have legal counsel, so she agreed to take “voluntary departure.” She thought she would have time to come back to Iowa to say goodbye and then get on a plane to Mexico, but she never came back to Iowa. Elizabeth was taken from Danbury to someplace out east and from there, sent to Mexico.

Now this is the thing. Her parents, who are elderly and they are legal residents, stayed in Marshalltown and took care of the little kids, who are now five and seven. And the parents had sold all of their property. I had gone several years ago to Mexico, and I visited these people, and they had a beautiful home because all the kids had helped to send money back, and they were very happy there, but they wanted to be here with their kids. So they moved everything up here. So when Elizabeth went back to Mexico, there's the house, but there's nothing in it! Not a thing.

So she goes back, and there's her husband and herself. There's no work. There's nobody up here to send money back to them, and their kids are here in Marshalltown. And then the concern was how to get the kids back to Mexico so they could be with them. Well, the little boy was in second grade. He didn't want to go back to Mexico. And the little girl said she really didn't remember her dad. I mean, these are little kids! Two years is a lifetime to them. So they were living with the grandparents.

A couple of months ago, when school got out, Elizabeth's sister and brother-in-law drove the two kids—and put as much as they could fit that belonged to Elizabeth and the kids into their vehicle—down to Mexico and left the kids there with the parents. Elizabeth's parents are still living in Marshalltown, but those kids have never lived in Mexico, so it's really weird and sad, and it shows how the system does not work. In this case, we're deporting de facto American kids! These children were born in this country; they are American citizens. They were not legally deported, but given the situation, they were.

Then there's Felix and Cynthia from Mexico City. They had worked with a lawyer, a so-called lawyer, on their immigration papers [and] work permits, and everything was in process. But they were caught in a trap because this so-called lawyer had applied for them to be here legally as asylees, and Mexico does not get asylum. And Cynthia also had a deportation order against her. A lot of people who've been here for many years have a deportation order from a long time ago, and ICE likes to call in its chips: “OK, you've got this against you. We're gonna get you now.”

So she and her husband hired a real lawyer, who charged $10,000 to work on a case. So the lawyer decided to work on Felix's papers first as the main breadwinner. Felix worked in construction. He had a very good job. He's also an ordained deacon. He had his permanent residency and all that. They started to work on her papers, and one day—I think she was using another Social Security number with her own name, but ICE went to where she worked and arrested her. They took her away, and she did not come back home. She was taken to Des Moines. She wasn't there very long, and she was deported to Mexico. She was either given a ten-year bar or a twenty-year bar, which means she cannot come back legally within that amount of time. If she does come back and she gets caught, she will spend the remainder of that time in prison.

Now, they have four children: fourteen, twelve, seven, and five. So those kids are up here without Mom. Cynthia's mom came here and stayed for like six months. Shortly after Cynthia went back to Mexico, she [the mother] came and stayed here to help Felix get his feet on the ground in terms of how to handle these four kids without her. Cynthia's mom came on a visitor's visa. The kids were up here almost a year without seeing Cynthia. I mean, there's phone calls, and I don't know if they used Skype to talk—and Felix had gone back a couple of times to see her, but it's very expensive, so the deacon community helped him financially. He took the four kids down to Mexico two weeks ago to spend time with Cynthia, and then just before school starts, he'll go down and pick them up and bring them back. What Felix is hoping is that after being a legal resident for five years, he can apply to become a citizen, and then he can apply to bring Cynthia up as his spouse, so you're talking a long time.

So there's a family that's totally disrupted. She'll never get that time back again, and those kids will never get that time back again. I don't know if you have kids, but when one of the parents is gone, it's all up for grabs. The chaos that's involved is substantial because Felix works full time. The oldest boy is fourteen and the girl is twelve, and to expect them to take on the role of the adults in the house is asking a lot.

Then there's Martha and Moises from Mexico. When they came, they were both undocumented. And they settled in California and eventually made their way to Iowa, and there were lots of hard times and lean times in between, but today both Martha and Moises are citizens. They are realtors in town. Moises also works as a manager at the casino here, and their oldest daughter is married to an Anglo who's an engineer. They have a daughter who's in law school, another daughter who's in medical school, and the youngest son just graduated from high school and he's going to study graphic arts. So they really are a success story and where the American Dream should let everybody go. But there are way too many stories that are not like them. They are the exception rather than the rule, and a lot of it is personality, too. Martha's the kind of person who doesn't let anyone step on her. And a lot of other people—their whole life they've been stepped on, and they just want to stay out of the way.

Do the Anglo locals resent the Hispanics? There's some of that. But the people have also come to know the Hispanic people because they work with them, their kids are friends with them, they've seen them in the community. I think the Swift raid in 2006 did a lot to solidify positive attitudes in the community, but yes, there are some people who resent them, don't like them. And some people grudgingly say, “I guess it's a good thing they're here,” because all of our schools have expanded. They've put additions on, upgraded them, so the schools have grown. The hospital has a new OB wing. We have more than forty Latino businesses in town, and so, economically, it's been a boon.

Supposedly there aren't going to be any more mass factory raids like ICE did in 1996 and 2006. What they do now is go door to door looking for people, and they do it whenever they want. I think they're doing it all the time in different places. They get out these old arrest warrants—deportation orders—and find where these people are. I can't imagine how much money it costs to drag somebody down. People I know have said to me, “When we're in public, call me by this name because that's how people know me.” [She laughs at the irony.] To me, that is like the ultimate in poverty, when you have to give up your own identification: “My fake ID at work says Maria, so when I'm out in public I have to be Maria, but when I'm home I'm Christina.” That's really bad. And it's all out of fear that an ICE agent is going to come up and tap you on the shoulder.

There are also people who will turn other people in out of jealousy or just wanting to hold fear over somebody, like, “I know you're illegal, and if you do this or don't do that I'll call immigration.” Another thing that's a side effect are parents who don't have authority in the home because in a lot of cases kids will threaten them with calling immigration.

What boils my blood is that nothing is being done, truly. A couple of nights ago I went to Des Moines and saw the movie Papers, about five undocumented youths whose life in America is affected daily by their lack of papers and how their lack of legal status makes it impossible for them to drive or work or go to college. And we have an extremely high dropout rate in our high school, and a lot of them are Hispanic kids. One of the people in the film said that kids do really well until junior year, when they wake up to the fact that “I'm undocumented, so why bother? I'm not going to be able to go to college; I'm not going to be able to get a job.…” But we've also got some great kids who are working on getting this DREAM Act passed. These are kids who don't have documentation. Kids who are 4.0 in high school and took college-level courses. One girl said to me, “I took college courses when I was in high school because I wanted to graduate a year earlier than my friends, but now I'm two years behind my friends and they're going to graduate next year.” So it's really pathetic.

Is the American Dream still alive here? I don't know. To me, the American Dream is that everybody can have an opportunity to be happy. Is that happening in Marshalltown, Iowa? For some people it is. But then again, with the whole immigration thing, I think you'd be hard put to find anyone in the Hispanic community who does not know someone who is going through life's realities as an undocumented person. You know, it's sort of like the thing with cancer: everybody knows somebody who is struggling with this.

I sympathize with Arizona to the extent that I know it's got to be really bad there because I know what it's like here. I'm sure there's a lot of violent activity and drugs—if not there, then just across the border—and so it's fear motivated. The problem is that fear is contagious, so I don't know where it's going to end. I think Arizona stepped over the line. I think it would be great if everybody wore sunglasses and the colors looked the same. I think a lot of it is not just an immigration issue, it's a race issue. I really do. Because when people talk about immigration, they talk about Mexicans. They don't talk about the Canadians who are here illegally, who I've heard is a huge number. They don't talk about the other groups who are here illegally. There are Europeans who are here illegally. They came on a visa from another country, and then it ran out and they just stayed. But they look like us [white Anglo-Americans] and they look like they're supposed to be here, so it's OK. In Fremont, Nebraska, the city recently passed a law that to rent you have to prove you are here legally. I mean, to rent! Everybody rents. And that's Fremont, Nebraska!

DREAM ACT STUDENTS

The Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors (DREAM) Act is a piece of proposed federal legislation first introduced in 2001 by Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT) that would establish a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants who arrived in the United States as children, only to find out they had no legal status as adults. It would transition these youth out of the shadows and into being full members of society, allowing them to pursue college, serve in the military, or work legally without fear of being deported back to a birth country they have little or no memory of—and whose language they perhaps do not even speak. The bill would directly affect an estimated 2.5 million “Americanized” but undocumented immigrant students.

“These determined and dedicated young people need the chance to become productive members of our society,” said Representative Zoe Lofgren (D-CA), a supporter of the bill. “They never had a choice in their situation. Yet our law blames them for it and makes them pay a heavy price. We should not penalize innocent children for the actions of their parents, but should instead reward them when they succeed.”

The DREAM Act—or, as some call it, the American Dream Act—has been voted on several times before the House and Senate, but its passage has remained elusive. In 2007, it came eight votes shy of the sixty votes needed for passage, and while it has received overwhelming support from the general public in polls, the initiative appears to have become a political football, consistently discussed but never resolved.

In September 2010, the bill was reintroduced again, this time incorporated as part of the 2010 National Defense Authorization Act, but it failed to get a single Republican to support it, even among those who had favored the measure in the past, and fell four votes shy of passage.

In December 2010, the House of Representatives passed the bill in a vote of 216–198, only to have it rejected by the Senate, which voted 55–41 to block it from going to President Barack Obama—a proponent of the measure—for his signature. It was a painful setback for the DREAM Act movement, as only three Republicans voted for it, and its failure appeared to leave the immigration policy of the Obama administration in disarray, at least temporarily.

What follows is the oral testimony of three DREAM Act students who appeared on May 18, 2007, in Washington, DC, before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration, Citizenship, Refugees, Border Security, and International Law regarding a hearing on “Comprehensive Immigration Reform: The Future of Undocumented Immigrant Students.”

These are their stories, in their own words.

Raised in Jefferson City, Missouri, she graduated with honors from Helias High School, one of Missouri's top secondary schools. She was a member of the National Honor Society, the foreign language club, the tennis team, and the track team. She also volunteered extensively for the Vitae Society and the youth group at her church. She was also once chosen by Latina magazine as one of their Women of the Year. “I would like to become an attorney one day. I would like to work for advocacy, for people who are underrepresented, whether that be {in} immigration or other issues.”

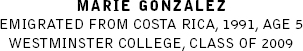

Good morning. My name is Marie Nazareth Gonzalez. I am a twenty-one-year-old junior from Jefferson City, Missouri, currently attending Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. I'm majoring in political science and international business with a focus on communication and leadership.

My family is originally from Costa Rica. I was born in Alajuela, Costa Rica, but have been living in the United States since the age of five. My parents, Marina and Marvin, brought me to the United States in November of 1991. Having come over legally, their plan was to become US citizens so we could one day all benefit from living in the land of the free. We sought to live the American Dream: the promise of a better education, a better life, and altogether a better future—what any parent would want for their child. Strong values and good morals have been instilled in me from a very young age. As long as I can remember, my parents have worked very hard for every dollar they've earned and in the process have taught me that life is not easy and that I must work hard and honorably for what I want in life.

That is exactly what they did. When they came to the United States, they had no intention of breaking the law or of making an exception of themselves. Unfortunately, the law is very difficult and complex. I am not making excuses for what happened, just trying to clear my family's name. Throughout all our years in the United States, we worked very hard for what we had, thinking that one day soon we would be citizens.

In April of 2002, our family's dream of becoming citizens was halted by a phone call. My father had been working for the state as a courier for the governor's office. The job was not prestigious in any way, but my father was very devoted to his job and was loved and respected by his coworkers. On one occasion, the governor even publicly stated his appreciation for my dad while he was making opening remarks at an event for Missouri high school sophomores that I attended. All of that ended after an anonymous person called the governor's office requesting that our immigration status be confirmed.

From that day forward, my life became a haze of meetings with attorneys, hearings, and rallies. When they heard that we were facing deportation, the community that knew us in Jefferson City rallied behind my family and me to an overwhelming degree. They knew we were hardworking, honorable, taxpaying people, and they fought to allow us to stay in the United States. Members of our Catholic parish, where my mom worked as a volunteer Spanish teacher and after-school care director joined with other community members to form the “Gonzalez Group” to rally support by collecting signatures for petitions and organizing phone calls. My classmates, teachers, and others also got involved because they considered me an important part of their community.

I was in high school at the time, with graduation quickly approaching. I was in my class's homecoming court. When it came out in the newspaper that I was being deported to a country I had not known since the age of five, people all across the country responded. They started a “We Are Marie” campaign, and tens of thousands called and wrote letters on my behalf. When I was a high school senior and our family's deportation date was looming very close, they brought me to Washington, DC. I got involved in advocacy for the DREAM Act. Unlike thousands of others like me who would benefit from the DREAM Act, I had little to fear from speaking out, since I was already facing deportation. When I gave the valedictorian speech at a mock graduation in front of the Capitol, I became a national symbol of the DREAM Act.

Eventually all of the work of so many people on my behalf began to pay off. My representative, Ike Skelton, and both of my senators, Jim Talent and Kit Bond, responded to the support from the community and got involved in the effort to keep me here. Eventually, though, all of our appeals were exhausted, and a final date was set for our family to leave the United States for good: July 5, 2005.

I remember that the weeks before that date were surreal. I was overwhelmed by the support I received. I appeared on national television, once with Senator Richard Durbin at my side, and was contacted by the media so often that I got tired of it. I thought, “Even if it is too late for me, at least it might help the DREAM Act to pass so that others like me won't have to face this ordeal.”

Then, on July 1, 2005, I got word that the Department of Homeland Security had relented and would allow me to defer my departure for one year. When I got that news, I cried—simultaneously with happiness and grief. Even though I would be able to stay, my parents would have to leave in just three days. The Gonzalez Group had made shirts and organized a float for the Fourth of July parade. So, the day before their departure, my parents and I rode in the parade with other members of the group that had been such a huge part of our family. Hundreds cheered us on and voiced their support and sorrow.

My life since April of 2002 can be easily compared to a rollercoaster. There have been times when I have felt like I was on top of the world, living out my and my parents' dream of being a successful young woman in her college career, only to be brought down by the realization that at any moment it can be taken away. The deferral of my deportation has been renewed twice, each time for a year. Last month, when they gave me until June of 2008, they told me it would be the last renewal. If the DREAM Act does not pass by then, I will have to leave. I recognize that I am lucky to have been allowed to stay as long as I have. Others in my same situation have not had nearly the support that I have. Even so, it is hard not knowing if I will be able to remain in school at Westminster long enough to graduate.

I am only one student and one story. In the course of fighting to remain here, I have been lucky to meet many other students who would benefit from the DREAM Act, and one of the reasons I wanted to come here and testify is to speak to you on their behalf. Unlike them, I can speak about this issue in public without risking deportation. I share with them in their pain, fear, and uncertainty. Their stories are heartbreaking and similar. In my experiences and my travels, I have come to the realization that they would only be an asset to the country if only given the chance to prove themselves. The DREAM Act has the potential to not only impact the thousands of students who would qualify but also benefit this great nation by allowing these students to pursue their education and their dreams of success.

I can personally attest to how life in limbo is no way to live. Having been torn apart from my parents for almost two years and struggling to make it on my own, I know what it is like to face difficulty and how hard it is to fight for your dreams. No matter what, I will always consider the United States of America my home. I love this country. Only in America would a person like me have the opportunity to tell my story to people like you. Many may argue that because I have a Costa Rican birth certificate, I am Costa Rican and should be sent back to that country. If I am sent back there, sure, I'd be with my mom and dad, but I'd be torn away from loved ones that are my family here, and from everything I have known since I was a child. I hope one day not only to be a US citizen but to go to law school at Mizzou [University of Missouri], to live in DC, and to continue advocating for others who can't speak for themselves. Whether that will happen, though, is up to you—our nation's leaders—and to God.

She was born in Lusaka, Zambia. After relocating to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, she came to the United States with her mother. After the death of her mother when she was fifteen, she came to study at St. Anne's—Belfield School in Charlottesville, Virginia. She excelled at St. Anne's and earned a scholarship to Hamilton College in New York. “I would like to give a voice to other individuals in my situation in terms of getting involved in nonprofit organization work {and} speaking at other forums such as this…without fear of backlash.”

Good morning. My name is Martine Mwanj Kalaw. I am a proud New Yorker employed as a financial analyst with the New York Public Library, and prior to that I was a budget analyst at the New York City mayor's Office of Management and Budget. Although I have lived in the United States for twenty-two years, I have an immigration nightmare I'd like to share with you. In August 2004, I was ordered deported.

My mother brought me to the United States on a tourist visa from the Democratic Republic of the Congo when I was four years old. She fell in love with and married my stepfather when I was seven years old. When I was twelve, my stepfather died, and three years later, when I was fifteen, my mother died. My mother had been granted a green card and was in the process of applying for permanent US citizenship at the time of her death. However, neither she nor my stepfather ever filed papers for me. Thus, when my mother and stepfather died, I was left not only without parents, but also without a path to citizenship.

Although I had no home, I was able to excel through my academic performance and through self-parenting. I attended prep school in Charlottesville, Virginia, with the assistance of a judge, who acted as my benefactor. After graduating from St. Anne's—Belfield School, I attended Hamilton College in upstate New York on a scholarship and graduated in 2003 with a concentration in political science.

All of this time, I knew that I had immigration problems, but it wasn't until I was in college that I came to fully understand the extent of those problems. I needed a new Social Security card in order to secure a part-time job on campus. But when I naïvely went to the Social Security Administration for the card, they referred me to INS. The next thing I knew, I was in deportation proceedings. I persevered while my case was pending, despite the looming prospect of removal to a country in Africa where I would not be fully accepted and do not know the language.

Soon after college graduation, I was a recipient of the Margaret Jane White full scholarship, which allowed me to graduate with a master's in public administration from the Maxwell School at Syracuse University in 2004. Academia became my security blanket that allowed me to be something other than that scarlet letter “I” for “illegal immigrant.”

Despite my academic record, I cannot escape the stifling nature of my immigration status and have therefore been unable to fully explore my full potential. My experience foreshadows what happens to immigrant students if legislation is not adopted to squarely address our status: we will be left in limbo, with a lot to give back to America but without provisions that will allow us to effectively do so. While I have been uplifted by the US education system, I have also been marginalized by the US immigration system.

In 2006, I met other potential DREAM Act beneficiaries who, like me, were facing deportation. They included Daniel Padilla, who graduated second in his class from Princeton University last year, and another young man who finished law school last year at Fordham. A third boy, a sweet and bookish teenager and honors student, talked about how it felt when the ICE agents came to his home in a case of mistaken identity but ended up arresting him anyway. He said, “They made me feel like a criminal…and I am not a criminal.”

I sensed the desire that many of these students share—to absorb all that there is to offer from the US academic system and then to give it back to their communities tenfold. Unfortunately, instead of support they face a constant struggle to fight for legal representation, for a work permit, and for a future.

My particular story has a happy ending, I think. In summer 2005, I began to work closely with Susan Douglas Taylor, my current counsel, beacon of hope, and constant support. In the spring of 2006, the Board of Immigration accepted my application for adjustment of status and remanded my case back to the immigration judge for a background check. Unfortunately, the immigration judge put me through a series of hearings and sent my case back to the Board of Immigration Appeals to reconsider their decision. This nearly broke my faith.

Just last week my lawyer, Susan Taylor, informed me that the Board of Immigration granted me an adjustment of status and my case is won. However, I am apprehensive, and I do not know how to process this information because I have been let down so many times with immigration law that my heart fears any more disappointment. Furthermore, the timing of the decision also means that I may not qualify for work authorization after May 24 and I may lose my job.

Although my immigration nightmare may almost be over, it is just beginning for countless others. I was very apprehensive about coming to speak with you today in this very public forum. I worry, perhaps irrationally, that it might in some way have a negative impact on my case. Lord knows that I have gone to the depths of human frailty in trying to deal with my immigration struggle. But it is my obligation to do what I can to prevent this anguish for other students. So I am here today on behalf of many talented and hardworking students who, like me, have grown up in the United States, but who cannot tell their own stories because if they did so they would risk deportation. I hope that hearing my testimony will help them by making it more likely that the DREAM Act will become law this year.

She was born in Germany after her parents fled Vietnam. Her family came to the United States to reunite with other family members here. In December 2006, she graduated from UCLA with a degree in American literature and culture with college, departmental, and Latin honors. She has worked as a full-time film editor and videographer. “I would like to get my PhD in American studies and start a production company that translates academic work into the film media,” she said. “I would also like to get involved with a nonprofit organization and create an oral history for individuals of marginalized communities.”

I hate filling out forms, especially the ones that limit me to checking off boxes for categories I don't even identify with. Place of birth? Germany. But I'm not German. Ethnicity? I'm Vietnamese, but I've never been to Vietnam. However, these forms never ask me where I was raised or educated. I was born in Germany, my parents are Vietnamese, but I have been American raised and educated for the past eighteen years.

My parents escaped the Vietnam War as boat people and were rescued by the German navy. In Vietnam, my mother had to drop out of middle school to help support her family as a street vendor. My father was a bit luckier—he was college educated—but the value of his education has diminished in this country due to his inability to speak English fluently. They lived in Germany as refugees, and during that time, I was born.

My family came to the United States when I was six to reunite with relatives who fled to California because, after all, this was America. It is extremely difficult to win a political asylum case, but my parents took that chance because they truly believed they were asylees of a country they no longer considered home and which also posed a threat to their livelihood. Despite this, they lost the case. The immigration court ordered us deported to Germany. However, when we spoke to the German consulate, they told us, “We don't want you. You're not German.” Germany does not grant birthright citizenship, so on application forms, when I come across the question that asks for my citizenship, I rebelliously mark “other” and write in “the world.” But the truth is, I am culturally an American, and more specifically, I consider myself a Southern Californian. I grew up watching Speed Racer and Mighty Mouse every Saturday morning. But as of right now, my national identity is not American, and even though I can't be removed from American soil, I cannot become an American unless legislation changes.

In December, I graduated with a bachelor's degree in American literature and culture with Latin, departmental, and college honors from UCLA. I thought, finally, all these years of working multiple jobs and applying to countless scholarships, all while taking more than fifteen units every quarter, were going to pay off.

And it did seem to be paying off. I found a job right away in my field as a full-time film editor and videographer with a documentary project at UCLA. I also applied to graduate school and was accepted to a PhD program in cultural studies. I was awarded a department fellowship and the minority fellowship, but the challenges I faced as an undocumented college student began to surface once again.

Except the difference this time is I am twenty-four years old. I suppose this means I'm an adult. I also have a college degree. I guess this also means I'm an educated adult. But for a fact, I know that this means I do have responsibilities to the society I live in. I have the desire and also the ability and skills to help my community by being an academic researcher and socially conscious video documentarian, but I'll have to wait before I can become an accountable member of society. I recently declined the offer to the PhD program because even with these two fellowships, I don't have the money to cover the $50,000 tuition and living expenses. I'll have to wait before I can really grow up. But that's OK because when you're in my situation you have to, or learn to, or are forced to make compromises.

With my adult job, I can save up for graduate school next year. Or at least that's what I thought. Three days ago, the day before I boarded my flight to DC, I was informed that it would be my last day at work. My work permit has expired, and I won't be able to continue working until I receive a new one. Every year, I must apply for a renewal, but never have I received it on time. This means every year around this month, I lose the job that I have. But that's OK. Because I've been used to this—to losing things I have worked hard for. Not just this job but also the value of my college degree and the American identity I once possessed as a child.

This is my first time in Washington, DC, and the privilege of being able to speak today truly exemplifies the subliminal state I always feel like I'm in. I am lucky because I do have a government ID that allowed me to board the plane here to share my story and give voice to thousands of other undocumented students who cannot. But I know that when I return home tonight, I'll become marginalized once again. At the moment, I can't work legally even though I do have some legal status. I also know that the job I'm going to look for when I get back isn't the one I'll want to have. The job I'll want because it makes use of my college degree will be out of my hands. Without the DREAM Act, I have no prospect of overcoming my state of immigration limbo; I'll forever be a perpetual foreigner in a country where I've always considered myself an American.

But for some of my friends who could only be here today through a blurred face in a video, they have other fears, too. They can't be here because they are afraid of being deported from the country they grew up in and call home. There is also the fear of the unknown after graduation that is uniquely different from other students. Graduation for many of my friends isn't a rite of passage to becoming a responsible adult. Rather, it is the last phase in which they can feel a sense of belonging as an American. As an American university student, my friends feel a part of an American community, that they are living out the American dream among their peers. But after graduation, they will be left behind by their American friends, as my friends are without the prospect of obtaining a job that will utilize the degree they've earned. My friends will become just another undocumented immigrant. Thank you.

Postscript

Three days after Tam Tran spoke out on her immigration plight, ICE—in a predawn raid—arrested her family, including her Vietnamese father, mother, and twenty-one-year-old brother, charging them with being fugitives from justice even though the family's attorneys said the Trans had been reporting regularly to immigration officials to obtain work permits. The family was released to house arrest after Representative Zoe Lofgren (D-CA) intervened, but the Tran family was forced to wear electronic ankle bracelets just the same. “Would her family have been arrested if she hadn't spoken out?” Lofgren said of Tam, who was not at home at the time of the raid. “I don't think so.”

In May 2010, Tam Tran, who was attending Brown University as a graduate student, was killed in a car accident in Maine. She was twenty-seven years old.

2001:

2001: