The “Roaring Twenties” continued America's economic growth and prosperity, as the incomes of working-class people increased alongside those of middle-class and wealthier Americans. The major growth industry was car manufacturing, as Americans fell in love with the automobile, which radically changed their way of life. On the other hand, the 1920s also saw a decline in immigration as the result of new quota-law restrictions.

KEY HISTORIC EVENTS

|

Immigration Restriction Act sets temporary annual quotas according to nationality and emergency immigration quotas heavily favoring northern and western Europeans, all but slamming the door on southern and eastern Europeans and causing an immediate drop in immigration. |

|

The Ku Klux Klan, virulently anti-immigrant, reaches the peak of its strength. |

|

National Origins Act sets a ceiling on the number of immigrants and establishes discriminatory national racial quotas, ending the period of mass migration to America. |

|

The stock market crash and resulting economic crisis pressure the Hoover administration to further reduce immigration and to order rigorous enforcement of the prohibition against admitting immigrants who are liable to be public charges. |

MIGRATION FLOWS

Total legal US immigration in 1920s: 4.3 million

Top ten emigration countries in this decade: Canada and Newfoundland (949,286), Italy (528,133), Mexico (498,945), Germany (386,634), United Kingdom (341,552), Poland (223,316), Ireland (202,854), Czechoslovakia (101,182), Sweden (100,002), Norway (70,237)

(See appendix for the complete list of countries.)

FAMOUS IMMIGRANTS

Immigrants who came to America in this decade (not all through Ellis Island), and who would later become famous, include:

Archibald Alexander Leach (“Cary Grant”), England, 1920, actor

James Reston, Scotland, 1920, journalist

Karl Dane, Denmark, 1920, actor

Gregory Ratoff, Russia, 1920, actor

Alan Mowbray, England, 1920, actor

Mischa Auer, Russia, 1920, actor

Arshile Gorky, Armenia, 1921, painter

Bela Lugosi, Hungary, 1921, actor

Pola Negri, Poland, 1921, actress

Vernon Duke, Russia, 1921, composer (“Autumn in New York”)

Hannah Chaplin, England, 1921, Charlie Chaplin's mother

Douglas Fraser, Scotland, 1922, union leader

John Kluge, Germany, 1922, billionaire/businessman

Simon Kuznets, Ukraine, 1922, economist

George Papashvily, Georgia (Caucasus), 1922, sculptor/writer

Isaac Asimov, Russia, 1923, writer

Greta Garbo, Sweden, 1925, actress

Willem de Kooning, Netherlands, 1926, artist/abstract expressionist

Ayn Rand, Russia, 1926, writer

H. T. Tsiang, China, 1926, actor/writer

Sir Charles Kingsford Smith, Australia, 1928, aviator

Gian Carlo Menotti, Italy, 1928, composer/librettist

Colonel Tom Parker, Netherlands, 1929, music manager (Elvis Presley)

Louise Nevelson, Russia, 1929, artist/sculptor

Her family was torn apart during World War I, then reunited for the boat trip to America. When she was ninety-five years old, she lived alone in an apartment in Franklin Square, New York, near the seven grandchildren and six great-grandchildren who “are my pride and joy,” she said. “I have one great granddaughter who is twenty-one years old. So who knows? If God lets me, I can stay a little bit longer and maybe become a great-great-grandmother.”

I was born in Kolomea, Austria. Now it's the Ukraine. It was a very beautiful place, and we had a very lovely family, and I was very happy. But my mother was always sick. She had problems with her gallbladder, diabetes, different things. My father was a peddler. He had a horse and a wagon, and he bought and sold dishes, earthenware. He would go away for a whole week to make a living, stop in different places, and come home for the weekend. Saturday was family day. All the children went to shul, and it was very beautiful. In the afternoon, we had dinner, and we went for walks near a river in the woods. Saturday nights, neighbors would stop by to visit, and they would talk and plan and dream and tell stories about what's going on in America, what they would do if they ever got there. Occasionally a person came from New York for a visit to see relatives, so they knew of New York and America from these visitors. We knew because my eldest sister had already left for America and she would write us. She came to America in 1914, just before the war broke out.

I lived in Kolomea till 1916 and the Russians occupied the city. We were told to emigrate. When the Russians come in, they said, they do horrible things to girls. So we made up our minds to leave. But they had no trains, so we had to walk. For four weeks we walked by foot and slept near the waters because on the main roads soldiers marched toward battle.

You could see houses off to the side of the road that were burned down by the soldiers. And city by city, my parents, my brother, my younger sister, and me, we walked until we reached the biggest city, Stanislaw. And then we were separated. My father got drafted into the army to fight the Russians. He was fifty years old, imagine! My brother was about fifteen. He was sent to the Italian front, near the Piave River, where thousands of soldiers got slaughtered, drowned. My mother, my sister, and I became refugees. We were put on a train by the government and taken to Yugoslavia. It was a train full of mothers and their children. Yugoslavian families would then come to the train and adopt you as laborers. Of course, they picked us because we were the cleanest, you know. [She laughs.]

I remember well a very wealthy family took us. But we didn't understand them because they spoke a different language. They had a big house with a little house behind it where we lived, and they had a gazebo with grapes and vines growing over it, and they had a farm. We would pick string beans, bushels of them. And in the evenings, even the meals, they didn't take us in their house. They served us outside—but delicious meals. We were there for several months, until we contacted my aunts in Vienna and this Yugoslavian family took us to Vienna by train. We lived there from 1916 to 1920, and I worked. I worked in a military factory, working machines that made uniforms. And we would sing. All these young Viennese girls. I was about sixteen years old then. And we got paid. I don't remember how much. They say you sing when you're hungry. Well, we sang all the time because there wasn't enough food.

They would give out ration tickets. My mother got up, as sick as she was, at four o'clock in the morning to stand in front of a dairy store where the government sold milk and butter and eggs. She would stand in line, and the line was long with poor people, and sometimes the food was sold out, so you got nothing. But most of the time she came home with a little food. When the war was over, we got in touch with my sister in America. She made affidavits and got us visas to come here; otherwise, we would have had to go back to Kolomea.

A few weeks before we were going to leave Vienna and go to America, I met William, my husband. He also came from Kolomea. We met through my brother, who was back from the war in Italy; my father was back, too. But William—we fell in love. So I promised him when I'd come to America I'd send for him, and I did.

I remember the day I left William and left for America. I was crying the whole night on the train. We went on the train through the different countries to the ship. We stopped in Innsbruck, Paris, a night here, two nights there, until we came to Le Havre in France. I even remember the dress I wore. I kept it for years. It was a nice flared skirt that I made myself. It went below the knee, and a blouse with a navy blue sailor collar and bow. I have pictures of it.

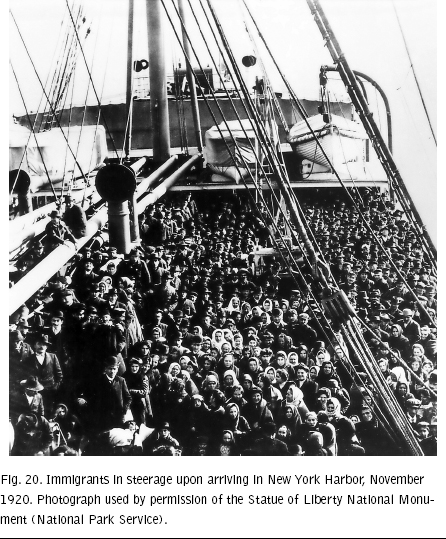

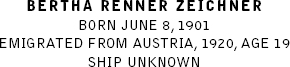

The voyage was hell. They gave us food, if you want to call it that [laughs], but we were so seasick we couldn't eat. We were not in first class. We were with the luggage in steerage. I remember the rats climbing over our limbs, and I would cover myself from fright…but we survived. We slept in bunk beds. There were a lot of different people. Lots of Italians. And they sang. I sang. We made the best of it.

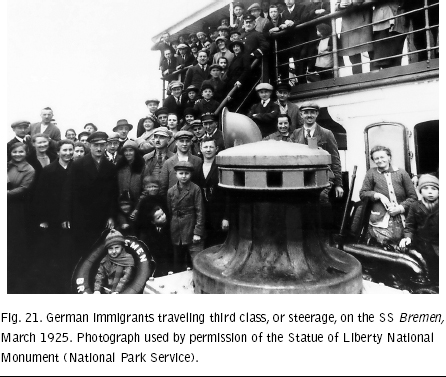

I was very happy when we arrived in New York. I don't know how long the voyage took, maybe fourteen days. When you're on the ocean, you think you'll never see land. We passed the eye examination, all the tests, and a day or two later, my sister came to pick us up at Ellis Island. We were very happy to see her.

She brought us to a three-room apartment in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. She had a husband and two little children by then, plus us: my mother, father, sister, brother, and me, five people. Of course, we brought few belongings with us, clothing and bedding mostly. In Europe, bedding was important, and we would spread it out on the floor to sleep. It was crowded, but at least our whole family was together…and we managed. My younger sister started work in a millinery. I worked in a clothing factory. My brother worked in pocketbooks. So we made a little money.

We started to look for a place to rent for ourselves. So many people could not live in three rooms. And we found one a few blocks away. In the front was a cleaning store and in the back were two rooms with a kitchen, so we rented it. And then my mother found a better place and we could afford a little bit more rent, like eighteen dollars a month from fifteen [dollars]. And we kept moving up until the time William, my boyfriend from Vienna, was supposed to come.

He was twenty-two when he came here, a year after me. And we got married. Got an apartment. He learned a trade. He became a furrier, and had ambition, and always reached higher and higher to become, from the machine, a cutter, you know, to make more money. When we got married, he was already making sixty-five dollars a week, which was a lot of money in 1923. I remember Saturday used to be payday. So he would come home with the envelope and let me open it if he knew there was a raise in it. And he was always getting raises. William was the type who always tried to learn. Long after everybody went home, he would help clean up and sweep the floor. Ambitious. Years later he went into the furrier business for himself, did very well, and we raised three beautiful girls together. [She pauses.] I'm tired now. I need to rest. [She smiles and closes her eyes.]

Born in Glasgow, he immigrated to America with his mother, brothers, and sisters when he was nine years old. He served in the tank battalion during the invasion of Normandy and was part of General George Patton's Third Army, which helped liberate Europe from the Nazis.

We lived at 184 Main Street, Glasgow. It was an apartment house. I remember Queens Park, where we went as children. We were six children. I was the youngest. Of course, I went to school. I remember getting lost in Glasgow as a youngster, just wandering off, not knowing where I was or how to get home, but I got there.

My father owned a wholesale lumberyard. By trade, he was a carpenter. He always suffered from asthma, and it was very damp there. He was thinking about coming to the United States or going to South Africa. He preferred South Africa, but my mother had relatives in the New York area, so we came to the United States, for which I'm glad. He continued as a carpenter after he came here. He had a fair amount of money. He built a couple of small apartment houses in Staten Island. Actually, he built three of them, and then during the Depression of the 1930s, he went broke completely.

My father came with my older sister as a visitor to see how he would like it, and he stayed with relatives in Staten Island. Later, we followed, my mother with the other five children, including me.

We took the TSS Cameronia, sailing from Glasgow to New York. It was my mother and five children. She bundled all of us, and off we went. It was very ordinary accommodations, and that's about all I can remember. It certainly wasn't in first class. My father was here about nine months when he sent for us. He decided this was the place where he would settle. It was with my mother's relatives in Staten Island.

Of course, when we got to Ellis Island it was very, very crowded—I mean, the Great Hall. A lot of hustle and bustle and luggage and people milling about. I don't know how long we stayed. I'm sure it was a couple of days. I thought Ellis Island was horrible, and I couldn't wait to get out of there. I remember that. Then somehow or other my father came and got us and brought us to Staten Island. That's where I stayed and went to school.

I recall my father had sort of run away from the military service in Russia. I say Russia because he was born in Brestlatovsk and so was my mother. I say Russia because that was the area between Poland and Russia as the map changed over the years. But they were all trying to escape military service. There was also an awful lot of antisemitism in Russia and a lot of persecution, and I'm sure that had a lot to do with it also. Why he settled in Scotland I don't know, except that I heard many stories of people who came over, went on a boat and it seemed forever, and the first port that the boat stopped, they thought it was the United States [immigrant profiteers told them Scotland was America]. My father had come with my mother because my oldest sister was born around 1902 in Russia. So they had to come together. They had the one child. They were in Scotland for about eighteen or nineteen years. So the trip to the United States was really a second resettling for my father and mother. I don't think they came because of antisemitism. As far as I knew, there was none. The reasons were mainly economic.

My parents hated anything military, and when I wanted to join the Boy Scouts and put on a Boy Scout uniform, they didn't like it a bit. They called that military, and they were very much against it. But I still stayed as a Boy Scout in Staten Island and grew up there.

They did talk Yiddish a lot, and then, of course, they learned English. My father read the Jewish paper called the Jewish Daily Forward. That was his main newspaper. But when we were in Scotland, we learned English and spoke it with a Scotch accent. They did talk Yiddish at home, but I did not.

When he came over here, besides doing this building, my father was quite a cabinetmaker, a little more on the refined side, a little more on the artistic side. He worked on the Staten Island ferries when they were building those in Staten Island. He had his own business.

Financially, we were comfortable at the beginning, especially after my father started building those small apartment houses when he came in 1921. I went to elementary school, PS 16 on Staten Island, and graduated Curtis High School. Then I went to City College, CCNY, for a couple of years. Then came the Depression, and it got the best of me, and I had to go out to work. It was very difficult finding a job. I managed to get odd jobs. My first job was as a messenger for Western Union on Staten Island. I went back to CCNY for another year and then left it again, and that was the end of it.

My father had a partner, and he lost it all [his business]. He also suffered from asthma quite severely. He started a grocery store. That was his livelihood—not great by any means, but that's what he did.

I finally joined a publishing company in 1940. I left them to go into the service in May 1941 and, of course, left the service at the end of 1945. I was in the European theater. My mother died in 1928, and my father died in the 1930s. He was not alive when I went into the service.

On December 7, 1941, I went to Jacksonville, Florida, to buy a return ticket on the train home. The radios were blasting away about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. When I heard that, I knew this was the day that I had been long waiting, expecting, and I turned around, didn't buy a ticket, and went right back to camp and just waited. I did the right thing because the MPs [military police] were rounding up all soldiers in the town and sending them back to camp, and everybody who was over twenty-eight was sent right back to the unit promptly.

Immediately after that, they started an officer candidate review board, and I went on the first group from the artillery brigade and was examined, graded, and so forth. Rather peculiarly, I was not in the first group. I was not in the second group. I was not in the third group. By April 1942, I was getting a little restless, and I went to my commanding officer, regimental commander Colonel Barnes, and asked him why I had not gotten a call to leave. He took out the lists of the brigade's three artillery regiments, and he looked up and down the list, and I was number ten on a list of 150.

I went to officer candidate school at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, in June 1942. I graduated from Fort Sill in ninety days—what they called the “ninety-day wonders”—became a second lieutenant, and they assigned me to a tank destroyer battalion. I asked them why I wasn't assigned to a field artillery unit, and they said, “You're too old for field artillery, so we had to put you with the tank destroyers.” Actually, the tank destroyer command had just started the school. It was a new concept. They needed officers. So I went through most of the war with the tank destroyer battalion in Europe.

When we went across, it was a very memorable journey. We went across on one of the so-called liberty ships. I was quite impressed by the amount of armament, and there was a navy officer on board, and I said, “What is this? What's going on? This seems peculiar.” He told me he was there on a guard ship for a troop convoy. I worked out a deal with him, since he had limited personnel, that we would take some of the personnel from the tank destroyer battalion and put them on watch at night for submarines. We had our submarine alert practices at dusk because that's the time when submarines generally surface.

We started out from New York Harbor with a convoy, and we had a right lead ship. Three days out, another convoy came out of the dusk from Boston and joined us to form a large convoy, which I understand was the largest convoy that ever went to Europe [for the Normandy invasion]. Our ship was still the right lead ship of the convoy. Along the line, we started dropping depth charges when we suspected submarines below. We didn't see any evidence of any, but I understood later on that somewhere a submarine had penetrated the heart of the convoy and sunk at least one or two ships.

When we got to the British Isles, the convoy peeled off to different ports. Our ship went directly to Cherbourg, France, and that was our first sight of what the war was about, all the wreckage that we saw. We debarked on a smaller landing ship and went to the coast of Normandy, and that's where we started our campaign.

I was finance officer for the trip, which is a menial job. I got rid of a safe that had been entrusted to me, which I never even looked at. I got rid of that at Cherbourg, and, of course, the unit was put on sort of guard duty against German attacks from the neighboring Jersey and Guernsey Islands until they decided to deploy us. Then we were moved north to the town of Geilenkirchen in northern Germany, near the border with Holland.

We were attached to the British Second Army at the time because they were right on the border of the American Ninth Army. And, of course, the activity, when we got up there, was very heavy. It was just a strange sight to see German planes flying over, strafing, dropping bombs. I saw American planes flying over, and for some reason you never saw the two get together. One came, one went, and you don't know why the two didn't meet each other in midair somewhere.

I recall as we were being led into Germany to the beginning of the Siegfried Line, the motorcyclist that came to us just got lost. He was leading a whole group. So I stopped the motorcycle and said, “Do you know where you're going?” He said, “No.” I said, “Then get behind me and I'll try to figure out where we're going.”

I was riding in a jeep. Behind me were a whole bunch of tank-destroyer vehicles mounted with seventy-five-millimeter guns or ninety-millimeter guns. It was Thanksgiving Day 1944 and we were on the Siegfried Line, and I had my first hot meal standing up inside of a German pillbox. The word “pillbox” is what they described as a very strong concrete fortification built by the Germans, which was certainly capable of thwarting any direct tank shells, it was that strong. But we fought our way slowly, bit by bit, and we penetrated the Siegfried Line.

I remember I had gone to take a shower at a coal mine, and as I came back, I checked into my radio, just to check in. My commanding officer barked, “Silence your radio and return immediately.” I wondered what happened. As I was heading back to the battalion area, I found out the Germans had invaded Belgium, and our mission was to reinforce First Army and contain the attack.

We got into the town of Marche, Belgium, in the Ardennes Forest. It was very cold. There was plenty of snow on the ground. This was the first time I saw the American army on the defensive. Division headquarters pulled back. We stayed forward, and the Germans had been in that town the night before. All civilians were sleeping in the cellars because of shelling, and, in fact, I took an upstairs place. You can't very well pitch tents in congested areas, but there was plenty of shelling, and it got so heavy that the glass in the room just shattered right in front of me. So I went down to the cellar for the rest of the night, more like on a stairway, because it was too crowded down below.

Slowly we repelled the German attack and straightened out the front line. It was very hectic. Everything was moving very fast. Tank destroyers got hit, were immediately replaced. It was so cold that the water in my canteen froze. The temperature was about twenty degrees below zero in the Ardennes Forest in Belgium. We straightened out the line, and when we did that I went back to Ninth Army, 13th Corps, and I was transferred to the Sixth Tank Destroyer Group. This was a break for me because I had always wanted to get out of the battalion. You couldn't get a promotion there. You just had to do what you could.

The corps commander decided that he would try to do what had been done in Third Army successfully, so I was chosen, as one of the liaison officers, to be attached to the Fifth Armored Division in a final push to the Elbe River in eastern Germany. I asked for Combat Command A, because I figured that would be the one which got the most action, and I was correct. It was commanded by a brigadier general, while the others were full colonels.

We moved along across the rivers Ruhr and Rhine. There were no bridges, so we built pontoon bridges. The bridges were manned by combat engineers. They were told to shoot any floating mines that may be in the river, or any other suspicious object. This was a one-way bridge, twenty-four hours a day, crossing the pontoon bridge into the main area of Germany, from which we would launch the final and main attack for the end of it.

Combat Command B and Combat Command C moved forward. My Combat Command A was in reserve, and I was rather unhappy because it was just too far behind. Then Combat Command B and Combat Command C stopped, and Combat Command A, we just roared up our tanks and off we went, passing through B and C, and took the lead to the Elbe River. We were the armored spearhead for the corps unit, followed by two infantry divisions, anywhere from twenty to forty miles behind us.

We were very successful in moving fast. We never stopped. We just kept on going, and German soldiers were passing alongside of us with their hands over their heads. They had gotten rid of their helmets and their guns, but we couldn't take them because we were not equipped to take prisoners any more than those in Desert Storm. Our tactics were to get to the objective as quickly as possible, and prisoners were out of the question. We just couldn't do that. That was not part of our mission.

I recall when we got to an airfield, there were six German planes during a two-hour period that were trying to land, never dreaming that the American forces had moved so fast to that area. We shot down every one of them. It was a huge brand of fire. One plane caught fire, careened out of sight, and crashed into one of our armored vehicles, killing all of the crew.

We reached the Elbe River and waited for the Russians to meet us. The Germans were on the other side. Day after day I would stroll up to the river, look at it. I still saw no sign of activity, no sign of the Russians. There was a bridge. I remember my commanding officer said, “You can be sure they [the Germans] won't let us take that bridge. They'll blow it up.” And sure enough, as I was turning my radio on, there was a loud explosion. The general's aide came rushing up to me. They had blown the bridge right in our face.

Later on, the able-bodied Germans, rather than surrender to the Russians, swam across this wide river, about as wide as the Hudson River, to surrender to the Americans. But in about a week or ten days, the Russians finally caught up and stayed put. We could easily have gone on to Berlin in this situation. Winston Churchill said, “Let's shake hands with the Russians as far east as possible.” But [General] Eisenhower held up the entire front, knowing that we would give up this sector of Germany to the Russians, according to the agreement of Franklin Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin at Potsdam.

So we sat there, a large area that later became East Germany. It could have been a lot shorter if we decided to hold the ground that we had taken. But political agreements take precedence over any military tactics. Eventually we gave this area over to the Russians. We moved further west, further back, and then we occupied our sector in Bavaria, which was the mission of the American forces.

At that time, of course, all units were disbanded, and I was given an assignment with the provost marshal officer, Third Army, which was commanded by General George Patton.

The job I took over was as a security officer for the Third Army at the prisoner of war hospital. It was an area of German military hospitals ranging from Munich south to Salzburg, Austria. The headquarters was in Bad Tölz, and General Patton took over the headquarters that had been held by the German Wehrmacht. He made that his headquarters in the town of Bad Tölz.

My mission was security control, to supervise these prisoners of war who were in the hospitals and disabled—typical enough. During that time, I went over to Dachau, that infamous camp where they had a lot of American DPs, or displaced persons. As I went through that camp, I went into one of the furnace areas where they burned bodies; you could see footprints on the wall. I repeat, on the wall, not on the ground, where they had stacked bodies high. I had the mistaken impression that one of the reasons why the Nazis had starved Jewish people was so they could get them so skinny they could fit into those very narrow furnaces. It just happened that those were the narrow furnaces that I saw, but there were others that were much larger. But, of course, starving them to death meant that they could cremate them easier after they gassed them.

We cleaned out Dachau and got all the displaced persons out of there, and we filled it up with German SS troops. I had gotten to the commander of the hospital, who was a full colonel in the German army, and he spoke very good English, so we were able to talk.

As we got friendly, he told me a story that I have never yet seen in any of the history books: how Germany started World War II. It was not started by Adolf Hitler. World War II was started by some elite Germans who were never satisfied in the Athletic Club in Berlin. They were plotting to revive Germany as a military power. This full colonel, a medical doctor, was offered the job of being chief of all the German medical forces. He refused. Instead of being a full colonel, he could easily have been a major general, but he turned it down.

When they chose Hitler, that was their mistake. He was supposed to be a front man. But he so fired up the German people that he pushed everybody else to the background, and of course the rest is history when you have a madman who thinks he can conquer the world and was not able to do so.

I retired as a reserve officer, which was compulsory at the age of fifty-three. I was a lieutenant colonel. I was forced to retire. That was the law. I have stayed in it as a retired officer subject to recall in case of any national emergency, and it still continues to this day.

1921:

1921: