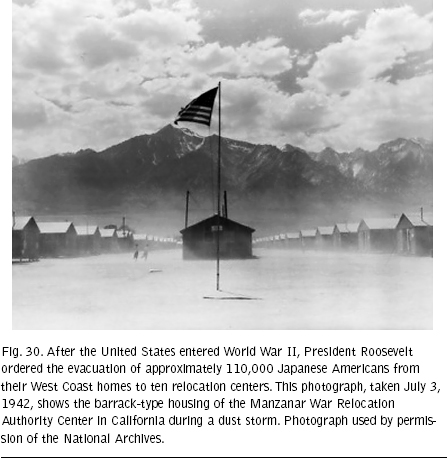

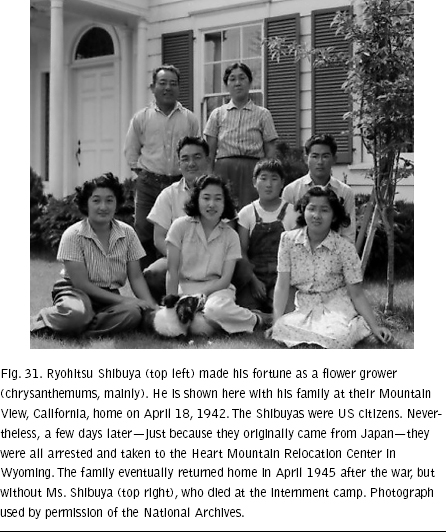

America's involvement in World War II limited immigration in the early 1940s, which had become not just a matter of economics but a matter of national security. National fears about foreign-born individuals continued to bubble up and were handled poorly, as when the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) organized internment camps and detention facilities for enemy aliens, even when they were not actually enemies or aliens. After World War II, INS programs addressed the needs of returning GIs and the conditions in postwar Europe as immigration slowly started to increase again, and has risen steadily ever since.

KEY HISTORIC EVENTS

MIGRATION FLOWS

Total legal US immigration in 1940s: 857,000

Top 10 emigration countries in this decade: Canada and Newfoundland (160,911), United Kingdom (131,794), Germany (119,506), Mexico (56,158), Italy (50,509), France (36,954), Cuba (25,976), China (16,072), Ireland (15,701), Netherlands (13,877)

(See appendix for the complete list of countries.)

FAMOUS IMMIGRANTS

Immigrants who came to America in this decade (here, not all through Ellis Island), and who would later become famous include:

Angela Lansbury, England, 1940, actress

Ricardo Montalbán, Mexico, 1940, actor

Vladimir Nabokov, Russia, 1940, writer

Yoko Ono, Japan, 1940, artist/John Lennon's wife

Bill Graham, Germany, 1941, music producer

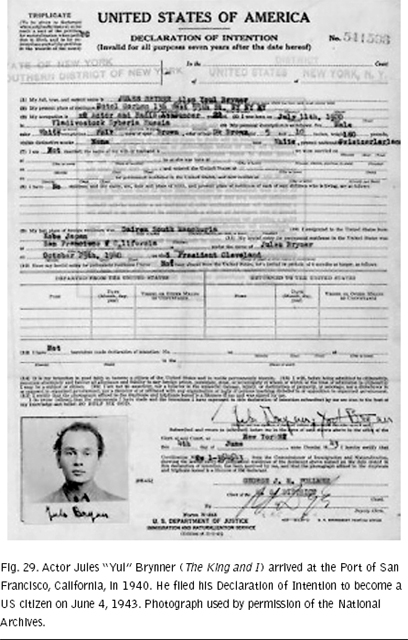

Yul Brynner, Russia, 1941, actor

An Wang, China, 1945, cofounder of Wang Laboratories

Ann-Margret, Sweden, 1946, actress

Yma Sumac, Peru, 1947, singer

Tom Lantos, Hungary, 1947, politician (California)

Madeleine Albright, Czechoslovakia, 1948, diplomat/US Secretary of State

Charles Trénet, France, 1948, singer

Max Frankel, Germany, 1948, journalist

Frank Oz, England, 1949, film director/puppeteer

The son of a prominent Jewish industrialist, his is an E. M. Forsteresque journey to America via Asia, India, and South Africa. He traveled with his brother, mother, and father, who left Yugoslavia to escape the Nazis. Their journey took many months, circumnavigating nearly half the globe, only to arrive in New York, find out his brother's visa had expired, and then spend nearly another month in detention on Ellis Island. This interview was conducted on Ellis Island itself for the Oral History Project in February 1991. It was the first time Paul had been back to Ellis Island since 1940, when his family first arrived. “I realize now that I should have come back sooner,” he said, “because there are so many memories attached.”

I was born in Vienna, although we lived in Yugoslavia at the time. My parents thought the hospital in Vienna was better than the hospital in the little town of Maribor, Slovenia. It's close to the Austrian border. We also had a better hospital facility in the town of Graz, Austria, where my brother was born. His name is Ivan. He is two years older.

My father's name was Vilko. He was a textile manufacturer. In fact, he was one of the founders of the textile industry in Yugoslavia. And he had both weaving and knitting mills in Maribor, and then he continued in that career when we came to this country. He started again and had textile mills here.

Our town was in a valley on the Drava River, beside a mountain that is actually the last in the Alpine chain. The name of the mountain is Pohore. The town at the time when we lived there had a population of about fifty thousand people. Now it's three times that size, and the people were, of course, Slovenian, but prior to World War I, that area was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and German was the second language. So almost everyone knew German quite well, but Slovenia tried to keep its language going, and therefore all schools and all official functions were strictly in Slovenian.

My father actually had his apprenticeship in the textile industry in Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovakia was quite advanced in that area, much more, of course, than Yugoslavia, and when he moved to Yugoslavia, he thought this would be a good area to develop the industry because of the availability of a labor force. But he had to bring some experts with him from Czechoslovakia who would run certain parts of the mills, so that it was a matter of training many of the employees, and this is just what happened, and it became a flourishing industry.

My mother's name was Margaretta. She was also Czechoslovakian and came to Yugoslavia after marrying my father, when he decided to move his business there. So they met while he was in Czechoslovakia. In fact, he was in business with my mother's mother, my grandmother, who was an importer and exporter and merchant in textiles in Prague and in other towns in Czechoslovakia. She was quite prominent in that business. This was unusual because women were primarily housewives then, but she had both a housewife career and a business career, and she met my father as a business associate, and that's how he met my mother. She actually worked together with her husband, but when he passed away she just continued the business.

My grandmother was a wonderful person. I remember her as being particularly generous and indulgent. She absolutely adored her grandchildren and spoiled us rotten every time she came to visit. She was a marvelous cook and we always looked forward to her arrival, not just for the cooking but for all the gifts she was always bringing. Her specialty was a preparation that involved a goose liver. It's taking the liver of a goose and treating it in some way, chilling it, and I remember the liver itself being in the middle of a sea of fat—all this, of course, solid after it's been chilled, very similar to the French foie gras. She made it for the holidays, for Christmas and Easter or whenever she would visit us.

My father's family was originally from Stupava, Czechoslovakia. My grandfather died before I was born. He was also a merchant. I don't know exactly what business he was in, but he had eight or nine children and kept a very close rein on everyone's doings and instilled in each a sense for business because they all have followed in his footsteps in that area.

When my father moved and established his first factory in Yugoslavia, on the factory grounds was a residential house, and we lived there a number of years. I was quite small, but I do remember it because it also had a garden and we had various pets to play with, ponies and, I think, a lamb. I still have photographs of that. I don't remember their names. [He laughs.] I do remember the dog's name that I got in Czechoslovakia. His name was Bonzo. [He laughs.] I don't know why I should remember that.

However, after a number of years we moved to the center of town and actually occupied an apartment from then on in Maribor. That was one of the most modern buildings at the time, and I think we had something like eight or nine rooms plus a kitchen and two bathrooms. I was about six. So it was just Mother, Dad, me, and my brother. And I was just starting school the year we moved in.

My brother and I shared a bedroom, but we had other rooms that remained empty. We also had a room for a cook and a room for a chambermaid. These were live-in help. My father was one of the most prominent individuals in town and financially very comfortable. He was not involved in politics—only in that, from the beginning, he drastically opposed the Nazi movement in Germany and made it well known throughout the town what his position was. And that was really the reason for our leaving Yugoslavia when we did. He knew that with a German takeover he and his family, and his property, would be the first victims if it came to pass. The fact that there were so many German-speaking people in the town—many with families in Austria and Germany—meant there was a considerable contingent of Nazi sympathizers. He knew this was a dangerous situation for us.

My parents were Jewish, but we became Catholics in the thirties. As far as the Nazis were concerned it didn't matter [laughs] because it was Jewish origin they were concerned with. My parents were not particularly religious. They did not observe many of the Jewish customs and observances. And since Yugoslavia was predominantly Christian—that is, either Roman Catholic or Serbian Orthodox—we wanted to conform pretty much to the rest of the population, so rather than stand out, we changed our religion.

So we went to church. We had two churches in Maribor. Church played a big part in everyone's life, particularly for children because religion was one of the required courses in school. And we had to go to church on Sundays and conform to all the various practices.

I enjoyed sports a great deal. Maribor is situated, as I mentioned, near a mountain, and in the winter we would go skiing. I began skiing at age four. My mother was the instigator there because she began to ski, and we enjoyed it ever since and went on ski vacations for Christmas and to Austria and other parts of Yugoslavia. Skiing was a very big part of our lives in the winter. In the summer we went to a little island in the middle of the Drava River which had swimming pools, and the rest of the time we would go on hikes and we also had horses. My brother and I became very fond of riding, and so every spring, summer, and fall we would be with our horses. We had a stable that was right in the middle of town, and many people in town knew us for galloping through the streets and holding up traffic once in a while.

My mother went to the Music Conservatory in Czechoslovakia but unfortunately didn't keep up with her piano, but she did ask me to take lessons, which I did at the same time I started school. I was not particularly fond of my teacher, who was a very demanding older gentleman. He required a great deal of my exercise time and I didn't always perform very well, as much as I enjoyed music. Many years later, I picked up the clarinet, and I still doodle around once in a while. But that's about as far as my musical education went, except that my brother and I were very fond of American jazz.

When the war began in September 1939, my brother and I were in England. My parents had sent us to Switzerland to learn French and then to England to learn English. We were about to return to England from Yugoslavia after our summer vacation when the war broke out and we didn't return, so we spent one more year in Yugoslavia. This was a touchy time because my father expected an invasion of Yugoslavia at any moment. And, in fact, we made various trips out of Maribor, which is so close to the Austrian border, to Zagreb and to other towns whenever he suspected something was happening at the frontier.

We spent the next summer, 1940, on the Adriatic at a resort, but by this time our papers were in order and we had received visas. My brother and I had student visas. My parents had visitors' visas. And without even returning to Maribor, we left from our vacation place to Zagreb and picked up our personal belongings, which we had with an uncle, an aunt, and cousin of mine who lived there. The aunt was my father's sister.

We said our goodbyes and took the train from Zagreb to Belgrade, then Belgrade to Sofia in Bulgaria, then Sofia to Istanbul. We stayed in Istanbul for about ten days awaiting papers that would allow us to spend some time in Bombay because we knew that we would have to wait for a ship there. My father had preplanned it all. By that time, the war had started. The Italians had occupied the southern part of France, so to go west, for instance, to reach Spain or Portugal where we might have gotten passage to the States, would have been very difficult.

So he decided on a longer but safer route, and that was to go through India and then take a ship. It could have gone west to New York or east and ended up in California. We weren't particular. We took the first one that came and ended up in New York. My brother and I were absolutely delighted. We were very pro-American in many respects, listening to a lot of jazz records, but we were also fond of American films, American books. We read Jack London a great deal, and we were very eager to come to this country. We knew very little American history. The schools in Europe, particularly Yugoslavia, were much more preoccupied with European history, particularly the history of Yugoslavia, which was difficult enough, the country having been first the kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes and then united as one country with three basic ethnic groups—the Slovenes, the Croats, and the Serbs—and a few minor groups such as the Montenegrins and the Macedonians. There was a great deal to be studied there. Also, there were periods under the Ottoman occupation from the Turks and the occupation under the Austro-Hungarian Empire. So we had to know this pretty well. America was a far-off land that we knew about only as the “great democracy” in the world and a land that “promised progress and freedom” and all the good things that we read about and wanted to be a part of.

My parents studied English. They took private lessons from professors in Maribor, but their English was never particularly good. They spoke well, but they both had very heavy accents.

In Istanbul we were staying at a hotel on the Bosphorus, a place called Tarabya, which was a beautiful Turkish resort place, and we had a wonderful time. I remember going fishing in the Bosphorus and the Black Sea and waterskiing and visiting Istanbul and the various places of interest: Topkapi Palace, the mosques, the Hagia Sophia. For two teenage boys, this was absolutely fabulous. Both my brother and I kept diaries. Just recently I rummaged through some papers and I found my brother's diary. I reread the story of our journey and he sketched some of the sights that we had seen, such as the minarets in Istanbul and later on some of the sights in Bombay and South Africa.

Then, one day, we crossed the Bosphorus by boat to the train terminal on the Asian side of Istanbul and from there took a train to Baghdad, which was a very long journey. It took two days and two nights. I remember the train compartment was not particularly well ventilated. This was September and it was hot, and I remember looking out the windows as we went through Turkey and later on Iraq on our way to Baghdad and [seeing] the extreme poverty of the people, some living under wooden planks made into a living area and maybe a goat as their only possession. Having come from a rather privileged background, this was the first time we were confronted with this kind of poverty.

We were in a first-class compartment, which was upholstered, but the ventilation was nonexistent so we had to open the window, and this was a coal-fired locomotive so we received a lot of soot. [He laughs.] It was a very uncomfortable trip. We had a dining car, which was adequate, I suppose, in terms of the food that was being served, but that was also hot and uncomfortable. And we were sitting next to people the likes of which I had never seen before up to that point. Some of them were Arabs, others were Turks, and they all looked very fierce to me.

I think we felt bewilderment, going through unknown places and into a bigger unknown as far as the future was concerned. I'm sure my parents were wondering if they had done the right thing. Did they take a step that was really necessary? We had left family and friends behind. What was going to happen to them? So knowing that we very likely would not see them again, certainly not very soon, there was a mixture of excitement in terms of seeing new things. but also sadness in leaving many things behind.

We were in Baghdad I think two days. I remember arriving after this long, tedious, and boring journey. Then, all of a sudden, we were surrounded by a mob of people who were trying to outshout one another, each one telling us they represented the best hotel in Baghdad. And so they were grabbing our luggage and beginning to load it on their various taxis, and finally we decided to go with the one who was the most aggressive because he had already gotten half our luggage and we ended up in a hotel that was not the best in Baghdad. But so be it. We had no other choice.

The hotel was, too, very warm. In Baghdad the temperature was something like 120 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade and there really was not very much shade anywhere. [He laughs.] The hotel was ventilated primarily by fans. The hotel rooms also had fans. Some of them were working, others were not. But we were so tired that we decided to make the best of it. I remember my brother and I shared a room and couldn't sleep because of the heat at night so we filled the bathtub with cold water and took turns lying in it. Then around five o'clock in the morning the sun came up and we walked out into the garden of the hotel and I remember some employees were lying on the benches in the garden and flies were all over them, going in and out of their mouths and noses. [He laughs.] It's a memory I still keep to this day.

The next day we all bought topees, tropical hats, to try to keep cool under the hot sun and we also went to a doctor to get shots. I think it was for diphtheria and various other diseases that we would likely catch in the Orient. Then we took a train from Baghdad to Basra and spent a couple of days there. Basra was a port city heavily involved in the oil industry. But we stayed in a hotel constructed by Germans and that was our first exposure to air conditioning. It was a wonderful change from what we had gone through the last few days.

I remember my brother and I went to a movie theater in Basra that showed a Tarzan film [laughs] with one of our heroes at the time, Johnny Weissmuller. The movie was interesting in that the film had some African natives fighting Arabs who were trying to capture natives for the slave trade. And when some of the Arabs were beaten by the African natives, the audience was not particularly pleased and started to heave things at the screen. [He laughs.] But then the theater manager gave a little speech in Arabic, which I didn't understand, and everything was much better.

After two days we boarded a ship from Basra to Bombay through the Persian Gulf. The name of the ship was the Barpeta. It was a British cargo ship, and the major cargo it carried was dates. It had maybe twenty passengers; half were American and English. They were all involved in the oil business in Iran, Iraq, and Arabia. The other half were Arabs. I don't know what nationality, but they all looked the same and they all dressed the same. One was a sheik who was traveling first class. His attendants, however, traveled second class, and my brother and I were in second class, so we got to know the attendants. The boat ride must have lasted a week.

We stopped in many ports in the Persian Gulf. We were able to go ashore in the ports. We saw Bahrain and a few ports on the Iranian side, and I remember the morning we spent in Karachi, Pakistan, which was a fairly large city, but half the traffic in the city was people riding camels or leading them! And it was very hot, so we didn't spend too much time in town. We went back to the ship, which then continued down to Bombay. The cabin was fairly ordinary. It had bunk beds for my brother and me, a small cabin. My parents had a much larger stateroom, which was quite comfortable, and the shipboard life was fairly ordinary.

In the morning we would get up early. Sometimes we slept out on deck because it was cooler. However, we had to get up very early in the morning because they started sweeping the deck around five or six in the morning. And then we spent the rest of the morning lounging in deck chairs being served bouillon. [He laughs.] I remember there was even some skeet shooting.

At night all the lights were out because of the possibility of U-boats [military submarines operated by Germany in World Wars I and II], so the crew was very attentive. There were English officers, and I got to know the captain, who had me up to his cabin because he said he had a son who was my age who was in England—in fact, who went to school very close to the school that I had gone to when I was in England, which was Brighton College. And so he wanted to know a bit about us. I guess he wanted to know who we were with Yugoslav passports going to India, which was sort of unusual.

India was another revelation to us. We had never seen anything like it. Bombay was a huge town with low buildings, crowded streets with people and cows wandering at random. These were holy animals and therefore were admitted anywhere. We arrived in Bombay about the middle of October, I would say, and it was still very warm. The monsoon season was about to start, and we were fortunate in obtaining an apartment rather than a hotel because we were waiting for a ship to take us to the States, to California or the East Coast. And we made some friends, my brother and I, in Bombay. We had met a Hindu couple on the ship, and they said we had to meet their children, and so we had a crowd of friends that we spent time with, both bicycling and going to a swimming place with pools both indoors and out. And we spent most of our time there.

In the evening my parents and I would sometimes, if it wasn't too warm, walk the various parts of Bombay, visit Malabar Hill and various restaurants, especially if they were European. There were some fairly good French and Italian restaurants in Bombay. The population was enormous, and all the people were Hindu. The European population could be seen primarily in some of the newer apartment buildings and some of the better hotels—the one we stayed at had four o'clock tea, including dancing, and they had their own swimming pool. We were in Bombay close to a month.

I remember many trips with my father to the American Express office and the American consulate in Bombay, so by the time the ship arrived we were ready to go. At that point we didn't know that our papers were not in order. For some reason or other, the American consulate didn't realize that my brother's visa was about to expire, and that's what really brought us to Ellis Island.

The boat was the SS Polk, for President Polk, part of the President Lines. The trip was from Bombay to Cape Town, South Africa, where we stayed for a day, and then to Trinidad and then New York. That trip was also long. It took about a month, from the beginning of November to the beginning of December.

The SS Polk was much larger than the Barpeta, and it was very comfortable. It was primarily a passenger ship with all kinds of distractions including a jukebox, which we had never seen before. There was dancing; there were games on deck such as deck tennis and shuffleboard. And we had our [jazz] records, and we immediately had a crowd around us because they all wanted to listen to the same music.

There were mostly Americans and many people from the Persian Gulf region who were in the oil business, either returning from a tour there or maybe just back from a visit with the family. Others were refugees like us. We had a Turkish family on board, some people from Greece, some people from Poland, all escaping the war in Europe.

The ride was quite smooth, except as we approached Cape Town. I remember huge waves, and there were some people who were seasick. We had regular updates as to what was happening in the world. Every morning a news sheet was posted on the bulletin board so we could read the events of the war, and again we were reminded of how fortunate we were to be on our way to America.

I remember one morning my brother woke me up very early and said, “You've got to come out and see this!” and he dragged me up topside. I was still in my bathrobe, and in the distance he said, “Now take a look,” and there was the Statue of Liberty, and it was a beautiful sight. We had, of course, seen pictures of it, but you really have no concept of size and grandeur, so that was just marvelous. Of course, beyond the Statue of Liberty was the Manhattan skyline, and that was equally impressive, if not more so. We had seen that in various films in the past, and to be there was just a terrific experience!

At this point we didn't realize that my brother's visa had expired. We thought this would be a formality and it could just be renewed because my visa was intact and we thought the authorities would take a look at this and say, “Well, since everybody's papers are in order, just the expiration of one visa is not going to be a major problem.” It turned out to be quite the opposite.

On arrival, as happy as we were to be in New York and a new life for all of us, we were disappointed almost immediately when the immigration officers looked at our papers and realized that my brother's visa had expired and that he would have to be taken to Ellis Island to await processing of a new application.

The rest of us were permitted to land in Manhattan, but my brother was only sixteen years old and we didn't want to leave him on Ellis Island by himself, so we joined him. We spent a little over three weeks there.

Most of our time was spent in the Great Hall. The day we arrived, we were given a physical exam. We were told that my brother's papers would be processed and that we would be advised as to the outcome “in due time.” We were given no time frame whatsoever as to when this would happen, so we had no idea how long we'd be detained. We entered the Great Hall and found someplace on a bench that also had a table, and we set up our headquarters there for the next three weeks. [He laughs.]

The place was filled. There were people in similar circumstances who had their papers looked at and processed. There were others who had been there for weeks, some for months. Some as much as a year. And there was a feeling of desperation because we had no idea when we would get out, and neither did anyone else. The other feeling was that this being wartime, and the influx of immigrants at such a high level, it was understandable that the United States would be very careful in screening the people that it admitted. And so there was a great deal of suspicion as to who was being admitted, and for that reason also, there was a feeling of privacy that you wanted to observe and not mingle with too many of the other detainees because you had no idea who they were, what their political persuasions were. There were rumors that half the people in the Great Hall were Axis spies or infiltrators so that we kept pretty much to ourselves, except my brother and I had met people our own age and we mingled quite a bit, playing various games such as Monopoly and exchanging pictures we brought along showing what Yugoslavia looked like. And the people we met showed us what various parts of the globe looked like where they came from.

The sleeping arrangements were highly regimented in that women had to sleep in their own dormitory and the men and boys in the other. I think it was the first time that my parents were separated. So it was pretty much a prison atmosphere I would say. And a fairly gloomy atmosphere most of the time.

There really wasn't much to do. We were given permission to walk outside in the courtyard twice a day if the weather was so inclined and even then we had to walk single file and for one reason or another we were not allowed to talk to one another, which was almost like a prison courtyard.

They fed us quite well though. We had not been used to many of the things that we received. I remember that most of the people, being from Europe, had never seen Jell-O before, and when Jell-O was served for dessert hardly anyone touched it, not so much because they didn't like the taste but because they didn't like the wobbly texture of Jell-O. [He laughs.] I remember the dining area had long tables where you just sat wherever you could as you marched in. But even that was under supervision. There were people standing around telling us when we had to be finished and leave. We were fed three times a day. Breakfast quite early, I think, because reveille was around seven o'clock or so with breakfast following shortly thereafter. And then lunch I guess maybe at noon, and dinner also quite early, maybe sometime between five and six.

The medical examinations were quite cursory because we all looked in fairly good health and therefore we didn't go through any extensive exams. Others who did not look healthy were checked more thoroughly.

I remember shortly before Christmas they put up a Christmas tree that was already decorated, somewhere near the center of the Great Hall, and it was an object of some criticism for almost everyone because it was not a very merry Christmas and it was almost ironic to have it there because the atmosphere just was not conducive to celebrating the holidays.

I would say three-quarters of the Great Hall was an open space with benches and tables where everybody set up headquarters and kept their bags and attaché cases and other belongings and stayed in the same place every day. The other portion was actually the visiting area, and that was just fenced off by a barrier, and we were allowed to go beyond the barrier and sit with the visitors. But that was the only partition. Visitors came every day in the afternoon. Most of the people were just marking time, not knowing what would happen to them.

We knew one family who came to visit us. In fact, they were very helpful in expediting our departure from Ellis Island. They retained a lawyer for us and also a clergyman, a Catholic priest, who was very helpful, and I think they were able to go to the various offices that required certification, such as the Yugoslav consulate in New York attesting to the fact that indeed we had been Yugoslavs and that my father was a prominent industrialist.

The person we knew in New York was the doctor who actually brought me to life. He was from Vienna and became quite prominent in New York, Bernard Achner. He had a wife and daughter and I remember the frequent visits on their part, and then we became close friends for many years thereafter….

One day, we were told my brother's papers were in order. The reapplication was accepted. There were a number of Ellis Island administrators and employees who circulated among the detainees from time to time, telling them the status of their situation or what was being done and if there was any change. And it was one of these individuals who came and told my parents that finally the papers were in order; we could begin packing to leave. This was a day or two before Christmas, and it was the biggest Christmas present we could have wanted. My parents were absolutely elated because until that point, we didn't know if we would be deported somewhere or if we would remain on Ellis Island for many months.

I remember for days just before that looking through the huge windows from the Great Hall—not just at the New York skyline but also the Statue of Liberty, which was facing the other way. She was showing us her back as if sending us a message. So finally we were on the ferry back to New York, and we could see the face of the Statue of Liberty, and things brightened up. By the time we reached Manhattan, our friends were at the dock. This was the doctor and his wife, and they took us to the Hotel Franconia on West Seventy-Second Street, and we had a suite and two bedrooms, I believe, and a little kitchenette, which was something new in hotels as far as we were concerned. We had never seen a hotel where you could do your own cooking. But this wasn't the only new thing we would encounter. I remember the first night we went to Times Square, and my father took us to a cafeteria and I'd never seen so much food—the trays weren't big enough to hold everything. We had a marvelous dinner, and afterward we went to the Astor Theater and saw The Great Dictator with Charlie Chaplin. How timely, right? That was a marvelous introduction, really, because a film like that could not have been seen in Europe at that time. And seeing the spoof on Hitler made us aware that finally we were in the land of freedom….

My parents adapted well here. They began taking intensive English lessons, and my father decreed that from now on we were not to speak any other language but English. And that was quite funny because their English was not as good as my brother's and mine. We often had to say things twice and in different ways in order to be understood, but as soon as we tried saying something in another language they understood—Yugoslav, Czech, German—they quickly shushed us and said, “Only English!” So that was the order of the day, and that remained the order from then on. They really wanted to project being American absolutely.

My father quickly looked at various business opportunities. He was fortunate in that he was able to get money out of Yugoslavia before the war and invested it in a small textile enterprise in Connecticut and later also in Massachusetts. And those became very active businesses, particularly once America got into the war because he was producing a number of materials needed by the armed forces, so he did quite well.

We never saw my grandmother again—my mother's mother. She stayed in Czechoslovakia. We received word sometime during the war, I think it was 1942 or 1943, that she had died after an operation. My aunt, my mother's sister, and her daughter and husband perished in concentration camps, and my uncle and aunt and cousin in Zagreb also perished in concentration camps.

We went back to Yugoslavia for the first time in 1985, some forty-five years after we left. After this trip, I wrote a book about my visit called Maribor Remembered, which was published in 1987, and there is a possibility they may make it into a movie. But they all say that, don't they?

I guess I'm in America.

She came from Letownia, a small, predominantly Catholic farming village east of Krakow near the Ukrainian border. She was nineteen years old when late the night of February 7, 1939, Nazi troops stormed her village and abducted her and thousands like her back to Germany to serve as forced labor on work farms to help feed the soldiers of the mounting German war machine. She was liberated by the English in 1945 and spent another four years in an Allied Forces military installation, where she met her husband and gave birth to her daughter, before coming to America with refugee status, eventually settling in upstate New York.

The town was really just a lot of farms, and we worked on a farm. We also made extra money making baskets. All different kinds. They say “Made in Poland” on the bottom. They sent them all over the world. I remember even to Japan. America and Japan were the best customers for us. And we were busy. Almost everybody in town made baskets. There was no factory. Everybody made them in their own home. We had a big room, and my father, my brothers, my sisters, and I all did it. Most of them were made of the wicker—wicker baskets. They were wholesale. We made about a dollar or so per basket. At that time that was big money.

I lived there about twenty years. I grew up in this town. There were about five hundred houses, farms, and they had straw roofs. Our house had about three or four rooms. We had no running water, and there was an outhouse, but we were happy because we didn't know any different. You have enough to eat and are well dressed, and it wasn't really too bad.

The house was made of logs, heavy logs. The house was just one floor. It was heated by a brick stove in one corner. We'd make a fire and then cooked on the top of some kind of iron, not stone, and we baked bread there, too. We got grain from the farm. Whatever we had, we raised ourselves. We would just buy salt and sugar and things like that, but not anything else. We had everything. To store potatoes, we dug big holes in the ground because in winter it was below zero, awful cold, and we covered the potatoes with straw and dirt and then dug out the potatoes as we needed them. They were really nice and crisp. That's how we kept things. And we had a storage room where we kept the grain and milled it to flour. That was a hard job. I was a young girl. Part of it was because there was very little meat. We would butcher one pig, a big one, before Christmas, smoke it, put some salt like salt pork, and that's what we had.

The summers were hot. I remember when I was about seven years old I watched cows and horses in a pasture on a rope. I had about two or three cows and one little calf. And they were so lovely I just hugged them. We would go to school and then come home and work in the field. There were other small children, ages seven, eight; we went in the field to get food for the cows. I mean, like, we'd go in between potatoes and wheat and dig the wheat for the cows. That was really hard work, honest to God.

My clothes were nothing to be proud of, believe me. At least I was lucky: I had shoes. But most children, only wintertime you went to school with the shoes on because it was cold, and when you came home, you had to put the shoes away and just walk barefoot because you had to save the shoes for the whole season. The shoes, most of them were custom made from a cobbler in town.

We went to school like eight o'clock in the morning for half a day, five hours, and so we didn't learn much, you know. There was no high school where I grew up. I had just a sixth-grade education. The school was four rooms. I lived almost across the street, so I walked to the school. But some lived six, seven miles, and they walked even in winter, through the snow, through the fields, to the school. It was just that way.

I had one teacher. And she was a mean one. She was strict.

If you did something they [the teachers] didn't like, they got out a big stick and they punished you [gestures with her hand] and sometimes you'd get it over here [gestures to her back], especially the boys.

We made different kinds of dolls and played hopscotch, different things. We had lots of friends growing up, especially in my home; we were well off compared to others. My best friend, she was very poor, and in her family there were seven children. The mother and father died very young, so the oldest brother took care of them. Many times I stole bread from my home and gave it to her to give to the sisters because I felt sorry for them. They didn't have shoes; they couldn't go to school. That was poverty! But even the old people, they were poor, too. They were undernourished. They had no meat. Maybe they had some bread, some potatoes, but most of the time they were hungry. When I look back now, I think to myself, “My God, what some of these people went through!”

So my mother, she had a big heart, she was a very good woman, and she felt sorry for them. So on Saturday or Sunday morning, she gave me cheese or butter or eggs or flour and milk to bring to the poor people to help them survive. The old, the babushki [women who wear head scarves], they said, “Oh, God bless you, child, and may God give you luck in your life, and your mother, too, because she's such a good woman.”

Our town was about 99 percent Catholic, and every Sunday we had to go to church. There were no excuses. We did have friends, neighbors, who were Jewish. And they were really friendly with us, but they were so strict about Kosher and what they wouldn't eat. But I was brought up that you had to go to church no matter what. In wintertime some people didn't go because they didn't have shoes. But summertime, all the older women, they went barefoot. They walked about six, seven miles to church, and High Mass lasted about three hours. And there was no pew for anybody, just a cold cement floor, and we had to stand or kneel, very few pews. There were choirs and an organ. This was a big church. It was the only church in town.

My mother married twice to two brothers. During World War I, my mother's first husband was hanged over by the church by about eight men because they thought he was queer, but he wasn't. They hanged him near the church. I have two half-sisters from him.

My mother later married his brother. I was the first child of the second husband. And my father, I'm going to tell you the truth—I don't even want to talk about it with my granddaughter. He was a very strict and mean man. He didn't respect us at all. But my mother, she was an angel.

Her name was Mary. She was from the next town over. She was a nice-looking woman when she was younger, but after my father, she was worn out. She had a tough life. She lost all her teeth, and there was no way to get [new] teeth, but she was an angel. She wouldn't hurt anybody. She was friendly, talked to everybody, respected everybody, and she was a very good mother. She gave us things which she couldn't have, because we were young, and she said, “You girls, you need it, you take it.”

There were five children in the family: two half-sisters from the first husband, and then from the second husband, my father, I was the oldest, and then I had a brother—he was younger—and then the youngest was the sister. But between us children there were no differences.

My grandparents had died except for my father's mother; she lived with us. She died when she was about seventy-eight years old. She wasn't sick. She just lay down and died. She watched us when we were small children, and she was very good with us. She had big pockets in her skirts, and she always had something in them for us. And she said, “When you're good, you're going to get something.” So she'd get things for us.

My father took care of the field with the horses and plows, heavy job. But the women, they did much more than the men. They worked in the field, came home, took care of the livestock like milking the cows and feeding every animal, and then cooked. I don't know how they did it. Believe me, they worked about twenty hours a day, summertime anyway.

I peeled potatoes; that was one of my jobs. We had a great big pot to cook potatoes, so I peeled them. And I got the vegetables ready, too. When I got older I worked from morning till night, and then I made the baskets. And then my father, he went to the city with the baskets to sell them, but he didn't bring back much money.

I knew about America because my uncles wrote to my grandmother. And they sent dollars once in a while. One dollar was worth nine or ten zloty, so you could buy an awful lot. One uncle was in New York and one in Massachusetts. But then when my grandmother died, they stopped writing. To me, growing up, America was like paradise.

There was a tavern in town, but the women, they didn't drink, they didn't smoke. They just worked the fields, made baskets, bore babies. But the men, they went to the bar and they got drunk, and they got nasty, mean, and beat up the women, the wives, and children. Oh, God, believe me. It was an awfully hard life.

My father was in World War I in Russia and he said how they almost froze to death, and how he prayed to God there would never be another war again. Well, when World War II came, I remembered his words. I was twenty years old. Everything was shut down, and the people were afraid because the Germans came with tanks and bombs, and the people didn't know where to go.

It was all so sudden. I remember it was February 7, 1939, when the Germans came and the war started. They dragged thousands of young people away, just picked them up. They dragged us to Germany to work on farms there, but you're a slave, because you don't know if you're going to be alive the next day or not; they might pick you up and put you in a concentration camp and kill you for nothing.

When they first came, they came right away with bombs and bombed part of the town, and many people were killed. After that, there was chaos because they had police soldiers in the fields, and the Germans, they came with the big tanks. They were bad. I can't even describe how bad they were. And then they took the people to Germany, boarding us on trains. They took me on February 7. We stopped in Krakow. I remember it was a high school, and we stayed there, and we slept on the floor for about four or five days, maybe more, and then we came to Germany. It was February 14 when we got to a farm there, and they were waiting for us.

The next day soldiers woke me up. I didn't understand German, but it didn't take me a long time to learn—especially when you're young, especially when you're with them all the time. They [the Nazis] showed me that I'm going to milk cows, clean them, clean the barn, everything. And I said, “Oh, God, I can't.” But they forced me. So summertime was really bad. We got up about three o'clock in the morning, and they would knock on the wall of the barn, and we went out to the field—there were eleven of us, all women—and we got food for the cows, came back, fed them, milked them, cleaned the barn, had something to eat, coffee and bread, and back to the field, worked until noon, brief rest, then back on the farm, cleaned the barn again, milked the cows, and we had dinner. I mean, I couldn't say that I was really hungry. I tell myself, “God punished me.”

We did have bread in Germany, thank God. And then we finished up and were ready to go on the field and work till about eleven o'clock at night. I was the strongest one, or the foolish one, because I got the men's job: we cut with a [gestures] scythe all day. I don't know how we did it. And then the next day, two o'clock in the morning, the knock on the wall came to get us up.

The Germans didn't take my mother or my father. They didn't get my sisters because they were hiding. They later told me they dug a hole under a barn, but the Germans destroyed it, so they had to keep digging. So every night they slept under the ground because the Germans would come at night and look for people to take away. So she said, “Maybe you're lucky that you went over there. At least you slept in bed.” And we did, for over five years. I went to Germany, and my brother went to a farm in Bavaria.

There was no heat where we slept. When you got up in the morning, you had ice on your featherbed because there was no heat. The bed was awful cold. During winter there was this much [gestures vertically with her arms] snow on the windows. And the German soldiers and farmers, they had special hot bottles they kept on the stove that they put in the bed before they went to sleep so they got some warmth. But we didn't have any, and you couldn't get any. They wanted work out of us, so they kept us alive. I mean, they fed us. We couldn't eat what we wanted, but at least you've got enough bread.

So we worked on this farm for over five years, and there was a farmer who had seven sons in the war. He was a friendly person, though, because the German people are cold, even to their own. But one son came back from the war briefly, and we asked him, “What's going to happen?” He said, “I shouldn't say this, but we [the Germans] are going to lose the war, and if we do, you'll never get out of this barn alive.” That's what he told us. He also said, “If somebody finds out that I told you, I'll be hanged, and so will you,” because they were hanging people.

We grew things on the farm for the German troops. They were very strict with the food. But we found a way to hide pigs so we had meat to eat. We wore wooden shoes. Wintertime there wasn't much work on the farm, so they sent us to the forest to cut wood by hand with a big saw, but it was below zero. We brought some food to eat, but the food was frozen. Still, we ate it because we were hungry. And we came back, and there was no heat whatsoever, nowhere except the barn, so we were lucky to come in the barn and warm up a little bit.

There were no Jewish women there. No Jews. Where I was working, there was eleven of us women, different nationalities, POWs: French, Serbian, Greek, Polish, Crimean, Byelorussian. We heard that there were Jews somewhere, but there was some kind of cover-up that there were not.

I remember near the end of the war somebody had a shortwave radio, and they said, “They're losing, they're losing, they're going to lose.” It was 1945, and the English came late one night with so many airplanes, the next morning you couldn't even see the sun. And the noise! The earth was shaking! Day and night they bombarded the Germans: boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. I remember it was April 27, 1945, when they came from the sky….

The German people were scared. They knew this was the end. We were happy that we were going to be free. The airplanes were flying very low, so when Germans were not there, we just waved to the English so that they knew that we were there. But when the Germans were there we couldn't do it. We had to lie down on the ground. Then the big tanks came in, and it was the first time in my life I saw a Negro. He was in one of the tanks. He was a big guy with big hands.

We were free! Some of the soldiers spoke Polish, German, but most spoke English, and they said we didn't have to work anymore, that we're going to be free, and they're going to evacuate us. They told us not to work in the barn, but the cows were making noise because they were hungry. They had to be milked. And we did, for the sake of the cows, you know.

The German farmer who owned the farm we worked on, he and his wife were worried for their sons. They were really afraid that something was going to happen to them because they didn't come back from the war. I felt sorry for the ordinary German people because they were Catholics, too. They were afraid. It wasn't easy for them either. They were free too now, but they still suffered as we did. They were afraid a bomb was going to come overhead and kill them.

When the farm was liberated, everybody was so happy. They hugged and shouted, “We are free! We are free! We're going to go home! We're free!” We were there until June, and they took us by truck to the military barracks. We were there for about four years. But after we found out the Communists were in Poland, we said, “We don't want to go home.”

The Russians we knew, just regular people, had told us how bad it was under the Communists. But at Yalta, Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill made a deal that when the war was over the Russians got Poland. It was impossible in Poland until 1979, when I went back. But my father and my parents were already dead.

I was married in 1945 in September in Germany. His name was Jacob. My first husband. Once a month they [Allied Forces] allowed us to go to church. Not the regular church, but a chapel beside a hospital. That's where I met him. He was Polish, too. Then Genny, our daughter, was born at the military installation in November 1946….

We had to have a sponsor to come to America. My husband had family that lived in Carnegie, Pennsylvania. My husband's uncle. They were our sponsor. But the uncle died suddenly, and we didn't want to be a burden, so we were transferred to my husband's distant cousin on a farm in Richfield Springs, New York.

We took a boat from Bremenhaven, Germany, the General Harry Taylor. It was a nice boat; especially because I had a baby, they gave us the officer's cabin. So we were lucky. But the men had to stay with the privates and soldiers upstairs. My first time on a boat, and it was a big boat. From Bremerhaven we stopped in Cherbourg [France], then New York. The ride lasted about ten days. We arrived at one o'clock in the morning at the Statue of Liberty. By eight o'clock they started to process us. We came with very little.

But we felt very safe and very happy to be in America. We had heard so much—that America is good and free, with opportunities for the people who care, who work and save. Some people thought dollars grow on trees. But I knew that you have to work and you have to save, otherwise you'll be poor again.

After inspection on Ellis Island they told us where to go because the sponsors were there to meet us. And they served us donuts [laughs] and different things to eat. We were there all day until seven o'clock at night, and then a mini-boat took us to the train station [in New Jersey], and they put us on the train and told the conductor to keep an eye on us because we didn't understand English. We each wore a tag. And then we took the train to Utica, New York. We arrived at twelve o'clock at night, and a farmer was there waiting for us and brought us to the farm [in Richfield Springs].

We slept in an attic, which wasn't my American Dream. Believe me, I cried all night like a baby. Somehow I was shocked. I expected America to be different. It was hot, and that May it was awfully hot—so much so the farmer even sprayed water over the roof to cool it down so we could sleep. At the same time we were grateful that they were good enough to bring us over here. They gave us milk, and things like that, and a roof over our head.

We stayed from May till the following February. Then we moved to Herkimer, New York, and we worked in a furniture factory. There were many Polish people there. My husband was a finisher and I was an assembler. So I put furniture together with a hammer and electric drill and hand drill. I was happy just to make some money. When I got my first check, I said, “Oh, I kiss him, I'm going to put it in a frame.” But I couldn't, because I needed money.

In the factory, American people worked there. We were not welcome. You could feel it. They didn't say much, but we were not welcome. Some people, they were already jealous of you, or something. I really don't know. They were not our own people.

When we worked, we got a babysitter for our daughter. She was four years old when we started to work. Then she went to school, which was right there, so there weren't any problems.

I should speak better English. I didn't go to school because I couldn't, because you've got to work, you know? In the home we spoke Polish all the time so that Genny would learn it.

For me, being in America the freedom was the thing: that you can go to church, you can speak, you can write, you can talk…. In Poland, people from the cities didn't respect ordinary people from the country, even the priests. Our priest thought he was the Almighty. I found it's not like that over here; you can go to your priest, shake hands, talk freely like I talk to you or to anyone. But in Poland you couldn't, and it was a free Poland when I grew up. But there's freedom—and then there's real freedom….

Several years ago, I went back to Poland to visit for about a month, and when it was time to leave, my sister said to me, “Aren't you sad to go back to America?” I said, “No, I'm not sad. I know I was born here, brought up here, but America is my country now, my adopted country. America is first and Poland is second because America is my bread and butter now and I am happy. I don't complain. I just say, ‘God bless America!'”

1940:

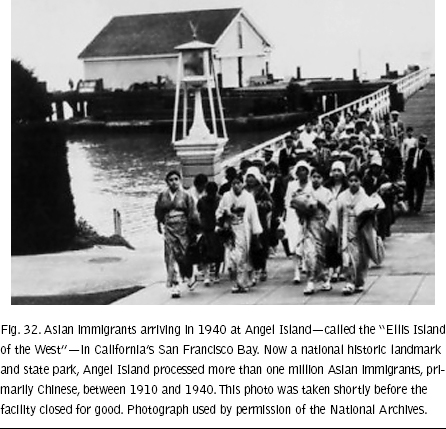

1940: