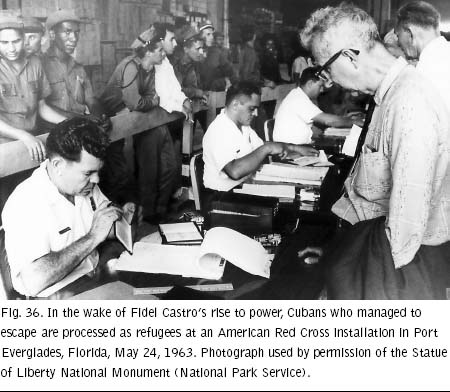

This decade saw America make great strides to restore itself as a haven for immigrants. The Refugee Relief Act of 1953, like the Displaced Persons Act of 1948, allowed many refugees, displaced by the war and unable to enter the United States under regular immigration procedures, to be admitted. With the start of the Cold War, Congress passed the Hungarian Refugee Act of 1956 and the Refugee-Escapee Act of 1957, offering a new home to the “huddled masses” seeking freedom, opportunity, and escape from tyranny. The drawback to America's open heart and outstretched arms was public concern that America's postwar policies were too open and let in Communists, subversives, and organized crime figures along with legitimate refugees, which only fueled the paranoia of McCarthyism, characterized by heightened fears of Communist influence on American institutions and espionage by Soviet agents.

KEY HISTORIC EVENTS

MIGRATION FLOWS

Total legal US immigration in 1950s: 2.5 million

Top ten emigration countries in this decade: Germany (576,905), Canada and Newfoundland (353,169), Mexico (273,847), United Kingdom (195,709), Italy (184,576), Austria (81,354), Cuba (73,221), France (50,113), Ireland (47,189), Netherlands (46,703)

(See appendix for the complete list of countries.)

FAMOUS IMMIGRANTS

Immigrants who came to America in this decade, and who would later become famous, include:

George Voskovec, Czechoslovakia, 1950, actor

Zbigniew Brzezinski, Poland, 1951, political scientist/statesman

C. L. R. James, Trinidad, 1952, historian

Ted Koppel, England, 1953, broadcast journalist

Patrick Macnee, England, 1954, actor (The Avengers)

Elie Wiesel, Romania, 1955, writer/Holocaust survivor

William Shatner, Canada, 1956, actor

Andrew Grove, Hungary, 1957, chairman/CEO of Intel

Rita M. Rodriguez, Cuba, 1957, international financier

Gene Simmons, Israel, 1957, rock bassist (KISS)

Derek Walcott, Saint Lucia, 1958, poet/playwright

Kevork S. Hovnanian, Iraq, 1958, real estate entrepreneur

Benoît Mandelbrot, Poland, 1958, mathematician

Itzhak Perlman, Israel, 1958, violinist

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, Switzerland, 1958, psychiatrist (On Death and Dying)

Fred Hayman, Switzerland, 1959, Beverly Hills retailer

Gloria Estefan, Cuba, 1959, singer

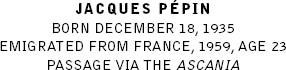

Jacques Pépin, France, 1959, chef

From an affluent Jewish family, hers is a dramatic story of a mother and daughter and their flight to freedom from Russian Communism during the Hungarian Revolution in 1956. Today, she lives in Miami Beach and serves as the executive director for the Center for Emerging Art, a nonprofit arts organization. Divorced, she has a daughter who lives in Croton-on-Hudson, New York; a son who lives in Forest Hills in Queens; and four grandchildren. “Am I happy?” Her voice cracks with tears. “I am happy. Well, I'm crying now, but I'm happy.”

I was born the day Germany bombed England. I emigrated from Budapest, Hungary, in 1956. I was fifteen years old. We came to the United States by plane. It was a military aircraft, part of the US Air Force that was bringing Hungarian refugees to the United States. We escaped from Budapest to Vienna, Austria. Then we got the notice that we were coming to the United States, and we went from Vienna to Munich and were put on an air force plane to Camp Kilmer, which was an air force base in New Jersey. That's where they were processing the Hungarian refugees.

I lived with my mother. I came from an affluent Jewish family, but everything had to go during Communism. With Communism, you're not allowed to be affluent. My mother didn't have to do anything, work, I mean, until 1954, when the Communist government was cracking down on all the Hungarians and if you didn't have a job you were put away somewhere. You had to have a job. So she got a job as an administrator. The Russians confiscated our home. The Russians took everything. Even when we moved into Budapest, it was into a smaller apartment. The Russians divided the apartment into two—because it was too big for a mother and daughter.

The Hungarian Revolution started October 23, 1956, against the Russian Communist occupation and the government. I was in my second year of high school, and me and my friends were gathered near this famous statue on the banks of the Danube River when suddenly university students and Hungarian revolutionaries took over a nearby radio station, which was about two or three blocks from where I lived.

Then that night and the following day, the Russians came in with tanks and all the military, and there was a lot of fighting and Molotov cocktails. Many people were shot dead on the street. I remember I wasn't allowed to go out until four or five days later. My mother didn't let me go out. And then my girlfriend and I were talking. It was always a dream, a fantasy, to come to America because my mother had sisters in America and my grandfather used to travel back and forth to America in the early 1900s because he was importing and exporting paprika and spices before I was even born. He brought one daughter to America in the 1920s and another daughter came to America in the early ‘30s, so for me it was always a fantasy to come to America.

My mother's sister used to send all these beautiful clothes and packages filled with things. To me America was the land of fantasy, the land of wealth. One of my mother's sisters lived in New Jersey. They had a 120-acre farm. The other sister lived in Miami Beach, and they had apartment buildings and orange groves. So I told my girlfriend, “Let's escape, let's go to America,” and like a good little girl I went home and I told my mother that my girlfriend and I are going to escape and go to America, and one thing led to the other, and my mother wouldn't hear of it. Not that way. She wanted to come, too! She had always wanted to come to America, ever since World War II, when we had to live in a ghetto.

So my mother, my uncles, and cousins arranged for a guide to help us escape. We took a train to a border city near the Austrian border, where we checked into a hotel under the guise that we were going to a pig roast in a nearby town. That night when the train stopped in the town, Russian guards interrogated us, and we said we were going to the pig roast. We checked into the hotel, and after midnight, the Russians came again. They knocked on the hotel room door and wanted to know who we were, what we were doing in the city, and again we told them the same story: we were going to the pig roast.

The following day, we actually did go to the pig roast. It was at the home of a family who had arranged everything for us, and we met the guide there who was hired to take us across the Austrian border. We had to take another small train to a small village on the border, and when we were sitting on that small train, a Hungarian peasant woman with a black dress and black scarves was looking at my mother and me, and she said, “They're walking to their deaths.”

Apparently some people were shot in the forest the night before. Of course, my mother's face went white, but nobody said anything. We just sat there, and then when we got off the train, the Russian guards were there again with questions, so our guide had us go to the back of the train and then under the train in the dark to nearby houses and gardens. We were hiding and walking in the dark through gardens and gates until we got to this forest on the border. We were still in Hungary. The Russians set flares to catch the escapees because Hungary was occupied, a Communist country at the time, and the Russians were looking for Hungarians trying to get out. Each time a flare went up, we hit the ground so they wouldn't see us, and the only thing we had was the clothes on our back, and my mother was carrying a man's attaché case which had watches and vodka in it in case we got caught—the Russians always wanted watches and vodka. We were walking a long time through the forest, hitting the ground each time a flare went up. It was me, my mother, her boyfriend, my father's cousin and his wife, and two little kids—I think they were eight and ten years old. I was already a big girl. I was fifteen years old.

My father had died in Siberia. He was in the Hungarian army, and then suddenly Jews were not allowed in the Hungarian army, and all the Jews were carted off to the eastern front and put into labor camps by the Germans. This was 1943–44. And that eastern camp was captured by the Russians, and it didn't matter to them whether they were Hungarians or Jews or Germans—a prisoner was a prisoner—and all the prisoners were taken to Siberia and so my father was in Siberia until 1948, when they had an agreement to let the prisoners go, but he had died. His best friend came back and brought my father's ring to my mother and told us that he was dead.

Back to the forest. So we walked a long time at night in the forest. One time we got lost, and it took a long while for our guide to find our way again. He finally took us to the first place that had a light on when we crossed the border. It was a tavern. I don't remember the name of the town, but there was a tavern, and my uncle took off his wedding band and he gave it to somebody to give us money so he could make a phone call and could call another relative who was living in Vienna, and he made the phone call to Vienna, and the Austrians put us up in a church basement that was set up for refugees.

The Russians could not touch us in Austria; they were not allowed. Austria was a free country. So once we crossed into Austria we were safe. However, the guide who took us across was arrested. Everybody knew that Hungarians were taking people and smuggling them across the border as escapees for money.

My mother's sister and brother escaped a month after we did, and they were arrested while trying to escape. They went back to Budapest and had to appear in front of a judge, and it wasn't until the second attempt a couple of months later that they were able to get to Austria.

My uncle's cousin from Vienna, who had been the director of the Vienna Opera House, came and met us with two very official, big cars—Rolls Royce, or a Bentley or something—and he put us up for a couple of days at his country home until he was able to find us lodging at a hotel in Vienna. Once we were in the hotel, my mother was able to find the agency that was processing the Hungarian refugees, and we went there and the quota was still open, and considering that my mother had two sisters in America, we were put on the top of the list. I think we stayed at the hotel for about a week to get the paperwork processed, and then they took us to something like a holding pen before they put the people on the plane.

So we were in these military-like barracks for about two or three weeks. Each day, people were waiting for their names to be called to get on the bus that was taking the refugees to Munich because they were flying the refugees out of Munich to America. Some people, of course, were processed to go to Israel. Some people went to Canada. Some people went by boat. It was December 24, Christmas Eve, when our names were called, and it was one of the most beautiful trips.

We got on this bus that took us from Vienna to Salzburg to Munich, and we drove through the mountains and the beautiful snow and saw the Christmas decorations, and literally when we got to Munich airport—I'm going to start crying in a second now that I remember—they played the American and Hungarian national anthems as we were getting on the airplane to come to America. It was very, very emotional. The flight took twenty-six hours. We had to stop in Iceland, and we flew into Newark, New Jersey, I think. I just remember wanting to be the first one off the plane, and I was!

We were taken to Camp Kilmer, an air force camp. We were put in marine barracks. We had them call my mother's sister, my Aunt Alice. She and her son came the next day and picked us up and took us to their farm, and I was put into tenth grade in Freehold High School in New Jersey. I understood English because as a young girl I had to learn English and piano. So I knew how to play piano, and I was learning English all along from an English lady who came and taught me when we lived in Budapest. So I understood some words. I was the first Hungarian refugee at my school, so my picture was in the local newspaper with a caption, something like: “The first Hungarian refugee, Ava Rado, in the tenth grade at Freehold High School….”

We stayed in New Jersey for a month, and my mother, may she rest in peace, decided that we were going to go to Miami Beach to her other sister, which we did. I was put in Miami Beach High School in the tenth grade. I went there for half a semester. We stayed with my aunt for about a month, until my mother—she just didn't know what to do. She didn't want to marry the boyfriend. So what she did was, my aunt knew a friend, and this friend was the mother of a very wealthy husband and wife. They had a winter home on Sunset Island, a very affluent island near Miami; his regular home was in Pittsburgh, and his summer home was in Canada. He was the head of a large trucking company. And the grandmother lived with them, and she said, “Why don't you and your daughter come live with us? You can help me cook” and help their daughter and the husband, who just ran his business, and he played golf….

So we moved to Sunset Island, I went to Miami Beach High, and then came April and we went on his private plane and he flew us all up to Pittsburgh. I went to high school in Pittsburgh, lived with them, and then my mother said, “I can't do this,” so we got our own apartment, and since my mother was a good cook, she wound up making Hungarian strudel for Weinstein's Deli in Pittsburgh. While all this was going on, her sister and her brother made it to Austria, but by that time, the quota to the United States was filled. So my aunt and uncle and cousins lived in a camp in Austria provided for the Hungarian refugees for two years before they were finally able to come to America with a visa in 1959 to New York.

So my mother and I moved to New York. My mother knew how to sew, and she had a friend who said, “I can take you into Bloomingdale's, and you can do some alterations.” She said, “Yes, sure, I can do it.” So she went, she did that for a while, and needless to say, she was really good at it and she wound up becoming the designer assistant to Pierre Cardin and Olivier [Gagnere], and that's how she wound up. She died in 1997.

I went back to Budapest in 1973. I was thirty-two years old, recently divorced, with a son and a daughter, and I said to my girlfriend, “I'm here in America seventeen years, but I want to go back.” And she said, “Well, why don't you? I'll watch the kids.” That was December 1. By December 3, I had my airline ticket and a passport ready to go, and I didn't even think about applying for an entry visa. For all I knew at that time I could have been turned back. So I got to the airport in Budapest and I said, “I'm here! I'm Ava Rado!” And I came to visit my grandmother, actually my step-grandmother. My real grandmother died in 1943. My grandfather remarried, so I had a step-grandmother. And it was a big emotional moment to knock on her door: “Here I am!” Of course, I called my cousin, my mother's other sister's daughter who stayed there, and she was in a very good position there because her stepfather was the head of the Hungarian auto factory and the biggest Communist and they traveled in diplomatic cars and all that—so I called her and said, “I'm here! Come pick me up!” And she came and she picked me up. In 1973 it still looked like it did in 1956, with many of the buildings still burned out from the revolution. I remember it was very gray, very dim. It was still under Communism, and that was weird for me because after seventeen years of living in freedom in America, I now had to report at the police station as to where I was staying, how much money I brought with me, what I'm spending my money on, etc. That was really weird!

I'll tell you one other thing. I love my life. My life is beautiful. I love where I am. However, I tell you if I didn't have children and grandchildren, I don't know where I'd be living. I say that because that's just a fact. I could live in the mountains with friends. I could live in Russia. I could live in any part of the world. So why am I in Miami Beach? Because I'm still stuck in Miami Beach. That's why I'm in Miami Beach. I had a house in upstate New York, and I just sold that because when I bought the house ten years ago, I bought the house with the fantasy and the dream that my kids would be coming over on Friday nights for dinner and I'm going to have wonderful weekends with the grandchildren and have great Sunday brunches, but the reality is this is America, where families are nuclear families. The parents and grandparents are really not in the picture, not like it was in Europe.

And one of the things that I really miss are the family dinners that we used to have on the farm in Budapest or even at my aunt's house in Miami or at my mother's house when we lived in New York—when all the aunts and uncles and cousins came—and those days are long gone. The new generations don't value this.

So what I have learned is, this is what we have. This is what is. And this is what we have to love. And it's a sad thing to say, but unless I say that…[pauses], I can't go through life not accepting and not loving what I'm doing and where I am. I have to accept it, and I have to love it.

Am I happy? [Her voice cracks with tears.] I am happy. Well, I'm crying now, but I'm happy. I'm fiddling with jewelry, actually.

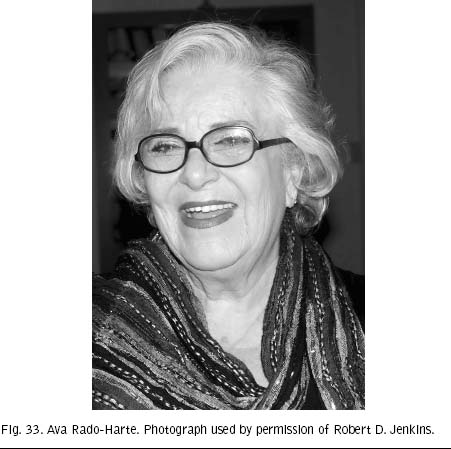

He is the longest serving doorman in New York City history. A member of Local 32BJ of the Service Employees International Union, he has been the doorman at 460 East 79 Street in Manhattan for more than fifty consecutive years! The twenty-story apartment building was completed in June 1960, and Steve, then thirty-three, came on as the doorman before the first tenant moved in, and he has been there ever since. Now eighty-three, he is friendly, good-natured, always smiling. He speaks in a thick Austrian accent—his words come out in a short, sweet, staccato. “For thirty-eight years I work six days a week straight,” he said. “But they cut me back. I only work five days a week. I'm off Saturdays and Sundays now.”

I was born in a straw house, my father's house, in a village called Szentpéterfa, right on the Austrian border but on the Hungarian side. It used to be Austria, and then it fell back to Hungary. So I see myself as more Austrian than Hungarian. My parents and grandparents were Austrian. My name is Austrian, everything is Austrian.

However, my parents met and married here in America, in Northampton, Pennsylvania. They came here when they were teenagers—I don't know what year, before the 1920s. I don't know if they were American citizens. They found each other here; then they made some money and went back home in 1926 to buy land in Szentpeterfa. A rich man was selling his land. I was born that year, 1926.

Within a short time, they returned to America and left me with a nanny, a very good nanny. She took care of me. I never can forget her. A nice lady, and she had her own kids—but she loved me the best. She was Hungarian. We were five together. We were four boys and one girl; they've all since died.

My parents worked, saved, and after five years in America, in 1931 came back home again, this time to build a house on the land they had bought earlier. They had a farm, and we worked the land. They came back with my two brothers: my older brother, Joe, and my younger brother, Frankie. They were born in America. I was the only one who was born in Europe….

I came to this country because there was the Hungarian Revolution in 1956. Before I came to America, I said to Frankie, “Come with me to Vienna and let's register, and we can go to America together.” Joe had already come here. And you know what Frankie told me? He said, “If you want to go to America, you can go to America, but I'm not going.” Because he loved the farm. He had gotten a house and everything from my father's first cousin when his son died in the war [World War II]. So Frankie stayed. He had a farm, a stable full of animals, and his animals were everything to him. He loved animals and the land. Six acres around the house. He said, “If you want to go you can go, but I'm not going.”

When I came to America, I wrote Frankie a letter. We were writing all the time. I said, “It's a good thing you did not listen to me and come here because everything here is so strange,” and also, he was not one, like me, to help himself. [He laughs.] I don't think he would have been happy here. Because he loved the farm. He was a farmer.

We lived close to the Austrian border. I had heard this one left, that one left. I knew Frankie wasn't coming. So I don't say nothing to nobody. I just went in the house. I had nothing with me. Nothing at all, and I went to the border. To the Austrian border—like from here to across the street. And I went there, and I spoke German, and I said to the Austrian soldier, “What will happen to me if I cross over and I stay?” And he said, “You're here already! You don't have to go back. Don't worry; you'll be taken care of.”

So I crossed the border to Austria in ‘56, and a lot of people knew me there, and I knew this village there very well. And then I heard you had to go to Vienna to register; America would take only so many refugees. There was a quota. I went to Vienna right away by myself—this was New Year's Eve 1956. Then they put us on a train to Bremerhaven, Germany, then a boat to New Jersey, and I came to America.

My older brother, Joe, was already living here in the Bronx. He came to the boat and picked me up. I hadn't seen him in more than twenty years. I didn't know if I would even recognize him, but I did. The boat landed in New Jersey someplace because I remember he came to pick me up there. I don't think it was Ellis Island, though. I was thirty years old when I came to America.

So Joe picked me up on a Saturday, and he said, “You have to rest up a little bit.” And I said, “No, I don't want to rest up—I've been resting enough. I want to work.”

So on Monday I went to look for a job, and I found one at Horn & Hardart restaurant [the first food service automats in New York City and Philadelphia] on East Fifty-Fifth Street in Manhattan.

The manager knew Joe, so Joe introduced me: “This is my brother. He just came to America and he'd like a job. He'd like to work.”

The manager said, “He can start tomorrow.”

So two days in America and I start to work!

I was at the restaurant for three years, and then I heard about this brand new building that was going up soon at 460 East Seventy-Ninth Street, and the super of the building said he wanted to see me. He was German. He was also the super of the building next door at 440 East Seventy-Ninth Street. So he managed both, and he told me about the doorman job, and I said to him, “Well, I don't want to quit my job. I have to make sure it's steady.”

And he said to me in heavy German, “You do what I tell you to do and you're going to be fine.” [He laughs.] And that was over fifty years ago! People started to move in in June 1956. I got my green card and citizenship early on.

I stayed here all these years because I like my job, and each time somebody didn't show up, they said, “Steve, don't go home. We need you!” I would stay and work sixteen hours a day. I was always available. How do I do it? You have to love people. Then people love you. I've gone through seven supers; I had no problem with them. [He laughs.] Also, I'm always on time. I don't think I was ever late in all these years. [He laughs.] I'll keep doing this as long as I'm healthy. Part of it is I cannot stay home. I love to be between the people. So this is my home. I like to go from home to home. I have two homes. One time I was going to work, and I told my wife, “I am going home now.” [He laughs.]

There's still a few tenants who live in the building from when I started. Most of them did not move out; they simply died. I had a good relationship with everybody, particularly the old-timers. I found my wife here also. The people who introduced us still live here. These people took an apartment when the building opened, and my wife came with them—she was a nanny for their little boy. So they told me about her. A friend said she's Irish. I say, “Oh, no!” Because Irish like to drink!

Turned out she was German. We were married a year later. Her name is Elizabeth. We had one son. He's in electronics. He lives in Long Island. He's married. I have four grandchildren. I don't see them too often. They don't come too often….

Elizabeth and I live in Pelham Bay in the Bronx. I was here in America five years and I bought my house. I have a nice garden. Everybody was jealous! My older brother Joe was jealous. Five years in America and he buys himself a house! I bought it from the previous owner. I asked, “Why do you sell your house?” He said, “Because my wife cannot walk up the stairs.” They were an older couple. I said, “I love your house—I'd like to buy it.” You know what he says? “You don't have to go to the bank to get a mortgage. The house is all paid off—we'll give you the mortgage!” He said, “If you love this house and you're only in this country five years, you don't have to go to the bank.” I told him how much we could put down, because my wife had a little saved, I had a little saved, and that's how we bought the house. And I will stay in that house as long as I live.

…My typical day to work, I take the subway straight. I live near the subway. I take the six train, the local, that's my regular train, no bus—but by the time I go home, the local is an express and then I walk home. I never take no buses, no nothing, and from Lexington Avenue, I walk a few blocks to here. When I get home, Elizabeth has dinner ready. My dinner is always ready. She cooks everyday something else usually.

She knows I love soup and cake. That's my secret to a long life: soup and cake! I used to bake, too. I still bake every so often. I used to bring it here to the building; people tasted it. Everybody knows my apple pie. They had a party for me. They say, “Are you going to bring something?” They gave me a few times party, you know? In the building. This last time in May [2010], they celebrated my fiftieth anniversary! And they didn't want me to bake. The party was for me, they said. They will bring the apple pie and they said, “It was good, but yours is the best!”

My favorite soup is chicken soup. Chicken soup I like. My favorite cake is any cake—but especially apple pie. Elizabeth knows how to bake very well. She makes cakes. In German we call it “torte,” and the big cakes she bakes, too. If we have parties, she makes cookies and everything she makes. Those are my two favorite things: soup and cake, and it has to be every day. When I went to doctor once, he said, “What kind of medication you take?” I was about forty-nine or fifty years old. I say, “Yes, I take medication. Homemade soup and cake! This is my medication….”

I went back to my village three times in my life. The first time was in the early ‘70s, when my parents were still alive. I went with my wife and my son. He was three years old. My wife's family is also German, so we went to Germany and then to Austria and then to my village on the Hungarian side. It was so nice to see the people. I still recognized them, and they recognized me.

The second time I went home because my father was going to die soon, so I saw him before he died. My older brother Joe is still alive. He's ninety. He's in Florida now.

The third time I went when my younger brother Frankie was sick, and you know what happened? In a few days I was going to come back to America; he said to me, “Are you counting your days to go back?” [Serious look, quiet voice.] He was counting his days to die! [Chokedup.] I was going to the airport, and I said to him, “I'm going to leave now—I'm going to Vienna to the airport,” and then Frankie, he just closed his eyes and he died. [He cries.] Just like that. He was seventy-six. The same morning when I was leaving he died. The same morning! He just closed his eyes. Like that.

We were very close. I was his big brother. We grew up together in our village. My parents came from America and brought him back home. So he was born in America but raised in Austria with me. I didn't see him too much because when I came here he stayed in our village. But we were always writing and everything.

I tried, but I could not change my papers at the last minute to stay for the funeral. I had to come back because my time was up on the visa. I said goodbye to him, but I never got to bury him. [He cries hard.] I wanted to stay, but I could not change my papers. [Long pause; then he gathers himself.] But at least I saw him before he closed his eyes.

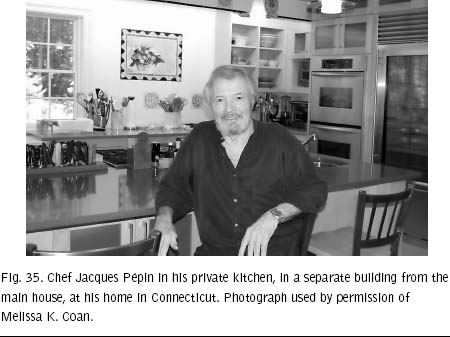

With a suitcase in each hand, he immigrated to this country in 1959, having been the personal chef of General Charles de Gaulle at the “French White House,” and holds the distinction of having turned down a similar position at the Kennedy White House when being “the chef” was at the bottom of the social scale. After two days in America, he found work at New York's famed Le Pavillon restaurant and spent ten years at the Howard Johnson Company. In 1974, he was injured in a car accident and doctors said he would likely not live, much less walk again. Jacques beat the odds and went on to become an internationally recognized French chef, television culinary pioneer, and author of more than thirty cookbooks who, along with close friend and legend Julia Child, paved the way for the success now enjoyed by so many of today's television and celebrity chefs. The recipient of numerous awards, he is among an elite group that has received the Chevalier de L'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres and the Chevalier de L'Ordre du Merite Agricole, two of the highest honors bestowed by the French government. A master teacher, he has imparted his extraordinary knowledge and experience to students for more than two decades at Boston University and the French Culinary Institute in New York, where he is dean of special programs. A devoted husband and father, he has been married for more than forty years to his lovely wife, Gloria, whom he met when he was a ski instructor and she was his student. “I recently celebrated over fifty years in America,” he said. “I came here and loved it, and I never wanted to leave.”

I was born in Bourg-en-Bresse, a small town about forty miles northeast of Lyon in France in an area very well known for the chicken, the chicken of Bresse, considered the best chicken in France: blue leg, white plumage and the red cock—so the red, white, and blue colors of the French flag.

I was practically born into the restaurant business. My father was a cabinetmaker by trade, but my mother opened her own restaurant, though she was never professionally trained, and my aunt had a restaurant, a second cousin had a restaurant, another aunt had a restaurant. I'm the first male to go into that business in the family, but often in America people think of the chef in French cuisine as purely male. Now it's true that in the Michelin Guide, most of the twenty-one or twenty-two three-star restaurants in France are [led by] male [chefs], but there are like 138,000 restaurants in France. So most of it is still cooked by women, believe me!

I grew up during World War II. At that time we didn't have any television, we barely had radio, there were no magazines—so we had kind of blinders on. As a result, you do what your parents do. So for me it was either being a cabinetmaker like my father or getting into the restaurant business like my mother, and I was excited about the restaurant business. All the excitement, the people, the noise, I loved it, so I went into that business. I never would have thought in my head I could become a doctor or a lawyer or one of those things; you didn't really stray from your family's business, or go outside the character domain of your family, and so you had kind of blinders at the time. Life was much easier than it is for young people now because, in a way, life was decided for you.

My mom had a very simple type of family restaurant. I remember my brother and I, before going to school in the morning, around seven thirty, we'd go to the market, which was a mile long beside a river. The market opened at three o'clock in the morning and finished at eleven o'clock in the morning. So my older brother and I, we'd go with my mother with a big bag, and my mother would walk to the market and buy on the way back, trying to get a better price—“Your case of cauliflower won't be good tomorrow. I'll buy it from you for half price”—and that's what she did because every day she had to go to the market and do that. I remember in 1959 at the restaurant it cost one dollar for the price of a meal, or five francs, and that included three or four choices for first course, then main course, a choice of vegetable, a choice of dessert. So you take a dish of each of those to create a menu, you had a carafe of wine with it, you have the bread, you have the service, tax included. One dollar, you know!

So to be able to do it for that, you didn't waste anything at all. Everything was used. And that kind of approach is reflected in my own cooking. I am very miserly in the kitchen, maybe because of that. Certainly we were used to saving money. We waste so much food here [in America], you know? When I go to a restaurant, I first go to the garbage to see what it is, and I'm amazed!

As I say, I grew up during the war. I remember my father disappearing to go into the Resistance. One time the Germans came to our house, and he jumped through the window and disappeared for like two or three years. He would appear occasionally and bring us food, sardines or something, because he had a wife and three kids.

We lived near the bridge of Lyon, the big bridge next to the railroad station—so it was an official point, a targeted area, and the bombardment started with the Italians throwing a bomb on the station there, and it blew out part of our house. Well, my father was gone in the Resistance. My mother was working in the restaurant with my grandmother. Fortunately we were all in the garden that day, so no one was touched, and we stayed with a cousin while the house was repaired. Remember, there was no telephone at that time, so my father would reappear, and all of a sudden he had come back to the house and we were not there, so he tried looking for us at some cousins' house.

We got blown up three times. The second time it was the Americans, who blew out the railroad as well as the same side of the house the Germans blew out, but we were not in the house either. The third bombing was when the Germans left France at the end of ‘45—they blew out the Bridge of Lyon, which blew out part of the house—so three times we were blown up, but three times we were not there, so we were lucky. But my father—it's probably why he had a heart condition—came back three times to find part of his house demolished. [He laughs.] Certainly I remember the Americans as well, running after the American tank, which was my first experience with chocolate and chewing gum which got thrown out of the tank by the GIs. I had had chocolate before the war, but I was too small to remember it.

For primary school education, you had to go to school until age fourteen to pass, and I was in that class when I was twelve, so I was way ahead in class and my brother was too. My brother became an engineer.

For me, I asked for a dispensation and took all of the exams when I was barely thirteen and went into apprenticeship as a chef because this is what I wanted to do. It's not because I couldn't study in school. I was doing quite well. But I knew from the beginning this was what I wanted to do.

At that time, my mother had a restaurant where she lived, in a suburb about seven, eight miles south of Lyon, and I left home when I was thirteen and returned to Bourg-en-Bresse, where I was born, and went into apprenticeship at Le Grand Hotel de l'Europe, which was considered the best hotel there. The chef there had actually gone to school with my mother, so she knew him, and so he took me in as an apprentice. There were four apprentices, and it was a three-year apprenticeship where you work seven days a week with no days off. You start at seven or eight o'clock in the morning and work until about ten at night, and at the end of the month you had four days off, so if there were four weeks in a month, I could take my clothes, my chef jacket, hat, pants, my apron, my towel, the sheet off my bed, everything back to my mother for her to wash and then bring them back. I would go back and forth to Lyon once a month.

When I finished my apprenticeship, I went to work for the season, a summer job, at L'Hotel d'Albion, a lakeside spa town in the Alps. It was a big hotel where you worked four months of the season, seven days a week, no stop because this is the season. I came back to work in Lyon at a restaurant for a couple of weeks before going to Bellegarde, which is a town close to Geneva, a small town where I became the executive chef for the winter at L'Hotel Restaurant de la Paix, which was something, considering I was not quite seventeen. In truth, though, except for the dishwasher, I was alone in the kitchen. The son-in-law of the owner who was the “real” chef spent most of his time in the nearby ski resort of Chamonix, plus the winter was pretty slow in sleepy Bellegarde, so the owner of the hotel took me on as the chef. I was there for about five or six months during the winter, returned to Lyon to work for awhile at a local landmark restaurant, and then I went to Paris. I was seventeen.

I had never been to Paris, but I told my mother I had a job which I didn't have, so I took the train. When I got there, I went to La Société des Cuisiniers de Paris, meaning “Society of the Chefs of Paris,” sort of like an employment center for chefs, and you can go there in the morning and you give your name to become a member. Then you're classified as second or first company, or chef de partie [also known as a “station chef” or “line cook”], or whatever your position, your age, where you've worked, and then they get you a job for the day. You work a job maybe three days, four days—sometimes a month or more—so there was always a job. In the morning, for example, you have a restaurant, a brasserie, and the chef doesn't come, or something happened, the restaurant calls La Société. I don't know why a place like this does not exist in New York, which has something like eighteen thousand restaurants, because it would be very useful.

So I worked in a lot of restaurants before working at the Hôtel Plaza Athénée on the Champs-Élysées. I pretty much worked there the longest time of any place that I worked. I worked at the Plaza Athénée for over six years. I usually worked on my day off, and very often during vacation time I went to La Société again to make extra money, so I probably worked in over two hundred restaurants in Paris on my days off.

In 1956, I was called into military duty. Usually they sent you to the army or sometimes to the air force, less so the navy, except for cooks—La Société had an arrangement with the navy to provide them cooks. In France, if you work on a destroyer, for example, you will have a petty officer to go with you to the market. You will have only so much money per day, so they want a professional who knows how to budget, buy, and it's not like the whole navy eats the same thing—they eat whatever the chef cooks that day, maybe something special like lobster for Christmas or the fourteenth of July [Bastille Day], so you really have to save your money. I was sent in the navy to boot camp in southwest France, and it was during the Algerian War, and then I went to do marine training. I was in good shape, so I was sent for military training, and I was supposed to go to Algeria in the marines, but I could not be sent at that point because my brother was there at the same time, so I ended up not going.

I was sent back to Paris to the admiral's mess in the center of Paris because I had worked at the Plaza Athénée [and] Maxim's. Then I had a friend from Lyon who I met there, and he was the chef of the secretary-treasurer, but he had never worked in Paris, and he said, “I would appreciate it if you would come and help,” because he was making dinner for the secretary of state and other people, and he said, “I'm not really that good in classical cuisine,” and I said, “Fine.” I had a room in town, so I was kind of free. And I started doing dinners for them at the Treasury, and then my friend was released from the army, so they asked me to stay on. The government was going through many rapid changes at the time. The prime minister then had all the power in France. The president of the republic was like the Queen of England—he didn't have any power before General Charles de Gaulle changed the constitution from the Fourth to the Fifth Republic, so with all the changes I ended up as “First Chef” of the prime minster at L'Hôtel Matignon, which was, and still is, the residence of the French prime minster. Then the government changed again, and it was at that time that de Gaulle came back to power, so I was there and stayed on with de Gaulle.

I admired him. To start with, de Gaulle was like six foot five. He was thin and tall, and he was practically blind, so he'd always look at you this way [sideways], so he appeared even more important, even though he couldn't see anything. [He chuckles.] His wife was very small. During the time I was with de Gaulle, I served heads of state like [President Dwight] Eisenhower, [President Josip Broz] Tito, [Prime Minister Harold] MacMillan, so as the chef it was a great experience. But it was a totally different world then than it is now because at that time the chef would be in a hole somewhere. You would never be called to get kudos or complimented or applauded or whatever. That did not exist, period. Never once. They didn't even know who was in the kitchen!

I saw General de Gaulle twice a week to do the menu for the week and especially for the Sunday meal after church when they held a dinner—the children, grandchildren, and so forth—but at that time, the president just went through the kitchen, said hello, and that's about it. You never had any kudos or compliments or anything like this. There was no publicity of any kind, so certainly that was one of the reasons that I didn't go to the White House later on: because I had no inkling of the possibility of publicity and the promotional value of this because it didn't exist. A cook by definition at that time was in a black hole somewhere, and that was it. I was used to being invisible…. You work with a young chef [now] and they want to find their dish; they want to create and find what they want to say. When I was in the kitchen, the idea was to work in a great house like the Plaza Athénée or Maxim's in Paris and to try to do it exactly the way it was always done in that house. So that the lobster soufflé, for example, at the Plaza Athénée—which was pretty famous—well, any one of the sixty cooks in the kitchen could have done it and not known the one who had done it. So the idea was to identify yourself with that, rather than now [when] it's the opposite; to detach yourself from that and be different or peculiar or whatever, which is another training altogether. [He laughs at the irony.]

By 1959, I wanted to come to America. Everyone wanted to come to America! And at that time there was more of a difference than there is now. I figured I would go, work for a couple of years, learn the language, and come back. I wasn't married. I could literally do whatever I wanted, and although my mother would have liked me to work in her restaurant and stay in France, I also had a friend at the Plaza Athénée who knew a pastry chef who worked in Chicago somewhere that led me to someone named Ernest Lutringhauser, a guy from Alsace with a restaurant in New York called La Toque Blanche, or “The White Hat.” He came on vacation every year to Paris, so I corresponded with him, and we met and he said, “Yes, absolutely, I can sponsor you if you want to work in the States.” At that time it was pretty easy because according to the law in the United States there was a quota. They accepted only so many immigrants from different countries every year, and the quota for France was never filled, as opposed to, say, Italy, where almost a third of the population immigrated in the 1930s and there was a huge waiting list going back eight, ten years before you could come to the United States with an immigrant visa, but France? No.

I went to see someone in the de Gaulle cabinet who said, “Go see Mr. Wood at the American Embassy. I'm going to give him a call and give him this letter.” Well, Mr. Wood happened to be the vice consul at the American consulate.

I had my green card in three months! It was the spring of 1959. I waited, I think it was ten days after the six-month limit that I had to leave because I wasn't ready to leave that fast!

I came on a student boat. Actually, my parents took me to Le Havre and I took the Ascania, which was an old converted luxury boat that was bringing home something like twelve hundred American students who were studying in Russia and all over Europe. It took thirteen days to come to Quebec, and everyone was singing and playing guitar late into the night, and it was the end of the fifties….

From Quebec, I took the train to Montreal, and from Montreal, I took the train to Grand Central Station in New York. I arrived with my two suitcases [laughs] and went straight to that man who had sponsored me. He put me up at a YMCA for two weeks until I found a room. In the meantime, he introduced me around. With the background I had, there was no problem finding a job. I came here on the tenth of September 1959, and a couple of days later I was working at Le Pavillon, which was the best restaurant in the country at the time, and a week later I was enrolled at Columbia University.

I went to Columbia to learn English for foreign students. I took an entrance examination, and I did fairly well, considering that I had been studying in Paris for like six months at a private school before I came here, and considering that I had no ear at that point. I couldn't understand anything people were saying. So I ended up in an intermediate class for English, and then I went on to another class and then another class for about two years until I got to what they call “English for Freshmen.”

I spent twelve years as a student at Columbia. I went from 1959, two or three years of English for foreign students, and eventually went into the regular college. At that time, there was no formal culinary degree. Didn't exist. I got a BA in 1970 and then went on to graduate school. I got my master's in ‘72 in eighteenth-century French literature, and I was working on a PhD, and I had finished the requirements for that, and I wrote my dissertation proposal, but they rejected what I wanted to write about. I had thought about quitting the kitchen and becoming a teacher, a university professor, because I loved literature, so I thought, why not combine the two? And I proposed a doctoral dissertation on the history of French food within the context of civilization and literature starting with the playwrights and poets of the sixteenth century, and they said, “Are you crazy? Food? This is too trivial for academic study….” So it was at that point I had enough. I said, “Fine.”

It's interesting because this is what I teach now at BU [Boston University]. We're offering a master's of liberal arts with a concentration in gastronomy, and this is the class that I have given for several years now. Ironically, two weeks ago, I gave the commencement address at Columbia for graduation, and the president of the university, a friend of mine, introduced me and said, “Considering that Jacques was refused to write his dissertation here because of his subject, which would really be appreciated like now….” So it's true: things have changed. It's another world.

My mother loved it here. Each time she came here she absolutely loved it, and she had her green card even though she wasn't living here. She'd come for three months, sometimes teach a couple of classes here, and each time she had to go back, she had to do a tax assessment. Even with a green card you have to pay your taxes before you leave the country. So each time she would come, it was like a nightmare for her to fill out those papers. She hasn't been here in the last few years. My mother is still alive. I spoke with her yesterday, actually. She was ninety-five a few weeks ago [in 2010].

Le Pavillon was a great restaurant, but for me, with the training I had in France, I didn't think it was that great, frankly. I thought it was good, but I had not worked in any other restaurant here, so I could not really make a comparison. In the spring of 1960, Pierre Franey, who was the executive chef there, had some problems with the owner, Henri Soulé, and it turned out that we all left.

A patron of Le Pavillon was Howard Johnson, the man who created the company, and he told Pierre, “You're going to work for me one day.” So eventually he asked Pierre to go work with him. Pierre had been in this country a long time because he came for the World's Fair in 1939, so he had been here more than twenty years. It was a time when Kennedy clan used to come to Le Pavillon. It was usually led by Joseph P. Kennedy, the father, and then of course everyone else; he was the man running the show. And at that point they came in spring 1960 to discuss the campaign or whatever, and they were always seated at La Royale, which was the best table and most visible one in the restaurant, and at that time a photographer snuck in and started shooting pictures of them. Martin Decré was the maître d of the restaurant, who the Kennedys knew well because they came there almost every week, and Joseph Kennedy said, “Martin, get that guy out of here!”

Soulé was at another table and overheard. Soulé was like Napoleon there. [He laughs.] “Decré You will do no such thing!” Soulé said. Every head in the restaurant turned. “It's only Soulé who decides who stays or who doesn't stay at Le Pavillon,” or something to that effect, some disparaging remark. He said it like, “Who do you think you are? You think you are already in the White House?”

The Kennedy clan left and never returned to Le Pavillon.

So at that point it also happened that the brother of Martin Decré, Fred Decré, was with Robert Meyzin, the general manager of La Cote Basque, which belonged to Soulé too. The two of them left to open Le Caravelle, so that was a big blow to Soulé. Roger Fessaguet, who was the sous chef at Le Pavillon, also left Pavillon to become the executive chef at Le Caravelle. Roger asked me to go with him there, and the whole Kennedy clan moved to Le Caravelle.

So a couple of months after that, Joseph P. Kennedy spoke to Robert Meyzin, now the owner of Le Caravelle, and said they needed a chef at the White House. So Roger Fessaguet, who was the executive chef, called me and said, “You should go there. I gave them your name, and they are looking and they are very interested.”

Meanwhile, Pierre Franey asked me to join him at Howard Johnson's; he needed an assistant. He made an appealing offer, and I said, “I don't know.” Pierre didn't tell me the White House would be a great thing for me, so it didn't really push me to go there, and for me, as I said before, because of the experience that I had in France, having been chef of the “French White House”—where I had never been in a newspaper, television didn't exist [for up-and-coming chefs], it had no bearing on my life. So I said, “I am starting at Howard Johnson's,” which was another world altogether, and I was at Columbia so I really didn't want to go to Washington, DC, and so I said no to the Kennedy job. They called me again a month later. They said they had looked at a couple of other people, and I said no again. With twenty-twenty hindsight you realize the possibility for publicity, but at that time I was totally unaware of it. Also, with Pierre, there was no limit to what we could do. Howard Johnson said we had to approve the food, so we started cutting down the dehydrated onion and put fresh onion, replacing margarine with butter, and started doing things like beef burgundy or whatever, and I started doing five pounds in the kitchen, and then I'd do fifty pounds, and in the kettle outside, two hundred pounds, and eventually three thousand pounds at a time. I worked with two chemists, and that's when I started learning about the chemistry of food about bacteria and quality control and so forth.

During that time, I was going to Columbia, so it was great. I worked at Howard Johnson's from seven o'clock in the morning to three in the afternoon in Queens Village near Jamaica, and then I went to college. I stayed with Pierre Franey for ten years, and then I left to open a restaurant on Fifth Avenue called La Potagerie with a group of investors. And I would not have been able to do that if I hadn't had the training at Howard Johnson's and was doing large production type of things. And then eventually, as a consultant, I set up the commissary at the World Trade Center with Joe Baum [who owned celebrated New York restaurants such as the Four Seasons, the Brasserie, and the Rainbow Room], and again, I would not have been able to do that if I hadn't had the training at Howard Johnson's. Even after, I was a consultant for the Russian Tea Room, the same way too. Howard Johnson's was a long American apprenticeship, but quite valuable for me….

I met Julia Child in 1960 when I was at Le Pavillon. Craig Claiborne came, and he had just started at the New York Times as a food critic. He came to do a piece on Pierre Franey, and I met Craig, and we became good friends right away. I lived on Fiftieth Street. Craig lived on Fifty-Third Street, and he introduced me to Helen McCully, who was the food editor at House Beautiful, and she was very feisty and very well known in this country at that time, and she had never been married, never had kids, so she kind of became my surrogate mother: “Don't wear this, don't do that, do this, do that,” fixing me up with all the girls in the office [laughs], and through Helen I met James Beard, and then in the spring of 1960, Helen told me, “You know, I want you to look at a manuscript.” She showed me a manuscript for a cookbook, and she said, “The author is a woman from California, and she's coming to New York next week. She's a big woman and has a terrible voice. She's going to come, so let's cook for her.” And that was Julia, but no one knew Julia because she had never done a book, so she'd never done television and was totally unknown. But what I want to say [is] within six to eight months after I was here in America, I knew the trinity of cooking, which was James Beard, Craig Claiborne, and Julia Child. So the food world at that time was quite small, extremely small, as opposed to today—it's another world altogether. And certainly the status of the chef, which, at that time, was considered uninspired and very low on the social scale, but now we are genius! [He laughs heartily.]

It has changed a great deal. In my early days, any good mother would have wanted her child to marry a lawyer or a doctor or an architect, but not a cook! But now, as I said, WOW! We are genius, you know? [He laughs.]

So I knew Julia because of Helen, and I started doing articles for House Beautiful, and then eventually I was asked to do a book, La Technique: An Illustrated Guide to the Fundamental Techniques of Cooking. I had finished at Columbia. I decided not to do my PhD. I didn't know at that time whether I was going to move into academia. Like many of us who are artisans, we have a bit of a complex about not having much of an education. Well, at that time at least, the study I did at Columbia prevented me from having a complex about not having an education. I could see that even at Howard Johnson's. They had college kids who graduated from Cornell [University's school for hotel and restaurant management], and Pierre Franey would be a little bit intimidated by them because they were college graduates, when they knew absolutely nothing about the food world and when Pierre was a much brighter person. But they couldn't do that with me because I had graduated from Columbia and they had absolutely no knowledge of food whatsoever, so it did change my view of many things, and I don't think that I could have done what I did in life if I hadn't studied at Columbia.

In 1974, I had a very bad car accident. I had fourteen fractures. I broke my back, my two hips, my leg, my pelvis. I wasn't supposed to live; I wasn't supposed to walk. So that was certainly a catalyst to start pushing me in the direction of writing about food, and coincidentally, at the time cookware shops with little cooking schools attached to them started opening up all over the country. When I went to the West Coast, I would go to a school for three weeks in San Francisco and another week in Los Angeles and another week in Eureka, California, and then they'd say, “We booked you for next year,” so I had a schedule like that for forty weeks a year, selling books all over the country and doing cooking classes and all that. I was the first. I was there when it started.

So that led to appearances on television, a morning show here and there, and I had already started with Julia on PBS in ‘62 or ‘63 after she did her book Mastering the Art of French Cooking and she said, “I don't want to do it anymore. You should do it.” So I saw some people at WNET in New York, WGBH in Boston, and they wanted to do it. They had to raise money, and I did a couple of shows, and one thing led to another. And eventually I did a series in Jacksonville, Florida, in ‘82 in conjunction with a book, and eventually I started doing them at KQED in San Francisco and have to this day. A series is thirteen shows. Each time we do a double series, or twenty-six shows, which is about 130, 140 recipes, so that's what makes a book. That's why I have so many books: because I do a series with each one. I think we've done something like thirteen series of twenty-six shows for KQED since 1989, I believe. My daughter Claudine and I have also done a bunch of shows together, and we're still doing them.

I hooked up with KQED in San Francisco because they asked me there, and because they raised the money. I'm part of the rostrum there, and that's it. They've always raised the money for me. I mean, if you look at Lidia Bastianich or Ming Tsai or Mario Batali or most of the chefs who are on television now, they are all executive producers of their own shows, but they have to raise the money or get involved in it, and I have never done that. If I had to, I wouldn't know where to start! So they [producers at KQED] raise the money for me, and I don't need to be executive producer because I'm the one who decides on the content of the show anyway. I do the recipes. No one can decide for me what I'm doing. So I am, in a sense, the executive producer, except that I don't have to raise the money, which—if I had to raise it, I would probably never do television again! Why? Because it's another world and I'm not good at that, calling people.

In addition to this, I never went to the Food Channel Network or others, although they asked me several times, because they wanted me to go with them, but they wanted me NOT to be with PBS at the same time, which I didn't like. And Julia and I were very happy with PBS because we don't have to kowtow to the sponsor or endorse any product. In fact, I don't have the right to endorse any product, so that makes it much easier—so I can focus just on being a chef.

What happened was Julia lived in Cambridge in Boston, and she bought a house there in 1949, I believe, so by the time I started teaching at BU, which was in ‘82, each time I would call and see Julia. I would have breakfast at her house or lunch, or we'd go out for dinner at night because she was very good friends with the person in charge of the BU program. So we decided to do a class together at BU, and almost from the beginning, the two of us were onstage doing demonstrations and it was great fun. And at some point I said, “I think we should do a special for PBS,” so we did a thing at BU called “Cooking in Concert,” which was three hours of us cooking on stage with a big audience, maybe five hundred people, which they taped as an hour-and-a-half special for PBS. This was the summer of 1982, and it ended up being one of the most watched cooking shows on television ever. Remember, the Food Channel Network didn't exist yet, so this was great. We continued doing classes together and doing more appearances together, and we said, “Let's do another one.” So two years later we did another “Cooking in Concert” special for PBS, and that was the catalyst or the genesis for the shows with Julia in the midnineties. Julia was around eighty-five at the time.

I was always friends with her, ever since we met in 1960. I mean, we argued all the time [laughs], but we were really good friends. People don't realize. They say, “Were you impressed when you met Julia?” Well, no. When I met Julia she'd never done a show; she hadn't done anything. I remember the first time we met at Helen McCully's, we actually spoke French. Her French was better than her English. She had just arrived from Paris. She had been working there for five years. She went to Le Cordon Bleu. She knew all those chefs in Paris, and she already joked that we started cooking together because she came to Paris in 1949 and I was in apprenticeship in 1949—of course, I was only thirteen years old. In the movie Julie & Julia, the part that related to Paris was really truly the way it was and the way I remember it because it was the same time when I was in apprenticeship that she was in apprenticeship. That's why that show took place from 1949 to 1960, when she did Mastering the Art of French Cooking.…

I am celebrating more than fifty years here. One of the reasons I stayed in America is because I thought the people were so nice—the easiness of life here, as opposed to Europe and the class system there, which was much more strict. People who come to this country come to get a better life, a better economic life, a better job, or because of political reasons or racial reasons or whatever, which was not my case at all. I had a very good job in Paris. I had family. So I didn't come here for a particular social or economic reason. I came here just to see. I loved it, so I stayed.

But America is different than it used to be. At that time, people would tell you how great you were; there was a humility. Now? It's “We are the greatest, we are the best, we are the strongest, and if you're not the greatest, not the best, oh my God, you're not American!” People have become so macho in this country! That did not exist before. People were not macho like that, and I don't know why it turned.

The face of America is quite different, too. I mean the social or the ethnic face of America is different than it was fifty years ago. If I were to advise someone about coming here, I would say the first duty is to learn the language! I came here and I learned the language! I didn't come here to speak Spanish or French or another language. That's kind of ridiculous. The language here is English and I intend to speak English, you know? And if you are here, whether you come from South America or any other place in the world, you should speak English! You don't come here to speak Russian—although people would not because there are not that many Russians or that many French or whatever. But if there are that many Spanish or that many Chinese, and [they] are in a certain enclave area of the country, you still have to speak English.

I would never move back to France because I'm much more American than French now. When I go there now I feel like I'm in another country, in a way. I feel kind of claustrophobic in Europe. I mean, the scale is different and the mentality is different. After fifty years here, I've become totally American. It would be difficult for me to live there. Contrary to many of my friends, it took them quite a number of years to decide if they were going to stay in this country and retire in France. For me, I have never had that hesitation. I came here and loved it and never wanted to leave….

My greatest pleasure now is cooking with friends. Cooking for the family. It all amounts to this, you know? Enjoying life is this. Like yesterday. Some friends came. We played boules [a game played with metal balls popular in France and Italy] for two hours. We drank five bottles of wine, and we cooked dinner together, and I did that the day before yesterday, too. I did lobster, corn, coleslaw. They did a book a few years ago which was about our last meal, and they asked fifty chefs what their last meal would be, and I said if you have extraordinary bread and extraordinary butter, it's hard to beat bread and butter. [He laughs.]

I don't know if there is one thing in particular I'm more proud of. I can't really think of any big disappointment. I did more or less what I wanted to do, you know? [He pauses.] Life has been good. I have done many things. I have been very lucky in many ways. Certainly, I feel lucky to do what I was able to do—so many books and TV shows. I have done more than I ever dreamed I would do. I love to paint; I even have some of my paintings in a museum. I'm very proud [more softly] of our life together, Gloria and I. We've been married so many years, more than forty years, since 1966, so that's a long time. And my daughter Claudine, I'm proud of her. She can get me crazy; she studied at BU for her BA, and then went for a master's in political science, and then dropped the whole thing and married a chef and gives some cooking classes. They have a child [pauses, smiles], so I'm a grandpa. That's good, too!

1950:

1950: