The 1960s were a historic decade for immigration, as America's current system of legal immigration dates back to that time. In 1965, Congress amended immigration law by supplanting the national origins quota system with a preference system designed to reunite immigrant families and attract skilled workers. This change in national policy meant that the majority of applicants for immigration visas were now coming from Asia, Mexico, and Central and South America, rather than from Europe. It marked a radical break with previous immigration policy and has led to profound demographic changes in America. But that's not how the law was viewed when it was passed at the height of the civil rights movement, during a period when the ideals of freedom, democracy, and equality had captured the nation.

KEY HISTORIC EVENTS

MIGRATION FLOWS

Total legal US immigration in 1960s: 3.22 million

Top ten emigration countries in this decade: Mexico (441,824), Canada and Newfoundland (433,128), United Kingdom (220,213), Germany (209,616), Cuba (202,030), Italy (200,111), Dominican Republic (83,552), Greece (74,173), Philippines (70,660), Portugal (70,568)

(See appendix for the complete list of countries.)

FAMOUS IMMIGRANTS

Immigrants who came to America in this decade, and who would later become famous, include:

Yo-Yo Ma, France, 1960, concert cellist

Carlos Santana, Mexico, 1960, rock guitarist

David Byrne, Scotland, 1960, musician (Talking Heads)

Seiji Ozawa, Japan, 1960, conductor

Plácido Domingo, Spain via Mexico, 1961, tenor/conductor

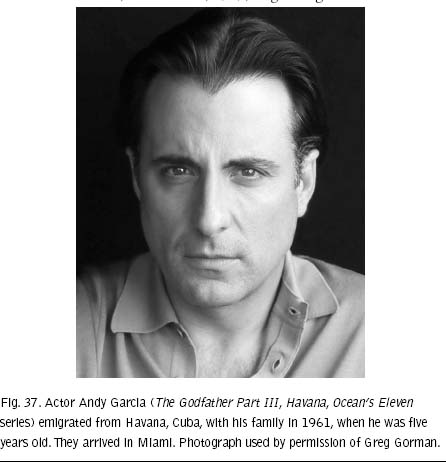

Andy Garcia, Cuba, 1961, actor

Zubin Mehta, India, 1961, conductor

Oscar de la Renta, Dominican Republic, 1963, fashion designer

José Canseco, Cuba, 1964, baseball player

David Ho, Taiwan, 1964, AIDS research pioneer

Peter Jennings, Canada, 1964, broadcast journalist

John Cleese, England, 1965, actor/comedian

Wayne Wang, Hong Kong, 1966, film director

Neil Young, Canada, 1967, singer-songwriter

Eddie Van Halen, Netherlands, 1967, electric guitarist

Leonard Cohen, Canada, 1967, singer-songwriter

Arnold Schwarzenegger, Austria, 1968, actor/politician

Deepak Chopra, India, 1968, self-help guru

Emilio Estefan, Cuba via Spain, 1968, music producer

Daisy Fuentes, Cuba, 1969, model

Dave Matthews, South Africa, 1969, singer-songwriter

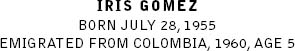

She emigrated from Cartagena, Colombia, when she was five years old and grew up in New York and Miami. Out of five siblings, she is the only member of her family to go to college. Today she is a nationally recognized public-interest immigration lawyer in Boston, an expert on immigrants' rights who has frequently lectured on the subject. An accomplished writer, she is the author of two poetry collections and the recipient of a prestigious national poetry prize from the University of California, and she recently published her first novel, Try to Remember, which draws on her personal experiences growing up as a Latina in Miami and her experiences as an immigration lawyer. “There's nothing more rewarding than feeling like you're able to earn a livelihood by helping others who are in more difficult circumstances than yourself,” she said. “I really believe that's the greatest way to have meaning—to feel that when I leave this world, I will have hopefully done something to have made it a little bit better for others.”

I was born in Cartagena, Colombia, right on the Caribbean coast, one of the most beautiful cities in the world. I lived there until I was five years old, and my extended family continues to live there. I was just back recently, and I brought my kids and my husband, and it's much developed now in the sense that the old colonial buildings, its heritage really, were all cleaned up, repainted, and propped up so that they would endure. But it's still preserved—its beautiful colonial character, and the balconies and the narrow streets with beautiful poetic names and the walls that go around the city. The Spanish built many of the forts in a similar way as in Cartagena, a very similar style of architecture.

We came to America in 1960. We came by plane. My father had come the year before and gotten a job in the New York City area. And so when we first arrived, he and an uncle were already working, so we emigrated the following year and made our way through several different housing arrangements until we finally got an apartment in Queens. My father worked in factories that probably no longer exist.

Unfortunately, when it came to learning English, I had to sink or swim when we first arrived in New York. I went to school, and I'll never forget the first days, just sitting there and not understanding anything that was going on except for people's gestures. Sometimes I think maybe it made me a better writer because it caused me to have to listen very acutely to what people were trying to convey, and I think that sort of helps you to be a good depicter of how people communicate.

Both my parents, particularly my father, really wanted the children to have a better life, and he struggled because he was one of eleven brothers and sisters and he lost his father at a young age. And so no one had a higher education or even the opportunity for that, and he really wanted that for his kids, and he really believed in the American Dream and saved up the money to bring his family here. At that time, there were three children, and my parents had two more when we got to the United States, but that was their hope: that we would live out the American Dream by getting a college education and doing better for ourselves than they had been able to do with working-class employment.

We were fortunate in that we were able to buy a house. We later moved to Miami, where a lot of our extended family had settled, and that was a time when the south Florida real estate market was much more affordable, so that people who worked in factories and were single breadwinners could actually accomplish that.

I was the oldest, so I was able to go to college. I went to Michigan State and eventually to law school and to graduate school. But my siblings ended up not going to college. My older brother went into the service and held ordinary employment jobs in Miami. Another brother died when I was twenty-one. My next younger brother became a UPS worker and committed suicide. I was already away in law school in Boston at the time, so I wasn't privy to all the details of what was happening in his life. He was still living at home. It was a real tragedy and a heartbreak for my mother, as you could imagine. My father had already died by then, so it was very sad and hard on her.

We went to Florida in ‘67, and for me it was a really wonderful experience in some ways because the growth of the Cuban community was just taking off down there and I felt a real home in my relationships with friends in my neighborhood, which was increasingly becoming a place where Cubans, as they got settled, got the support they needed as refugees to then buy houses, so our neighborhood in southwest Miami became very Hispanic. I found a sense of community in that culture even though we were Colombian, but I felt very grateful to have peers who were living like me in an American society, but also had families where Old World culture, traditions, and customs were very much a part of our consciousness.

I pursued writing; I just didn't pursue it as a career. I have always written since I was a young girl. I had a great interest in poetry; I just loved to write. I was always very good in my English classes. I edited my high school newspaper, and then in college I took courses in the writing program even as I was earning what was called a Community Services degree because I knew I wanted to have a job working with low-income communities. Then in law school I went to Boston University School of Law. I took courses in the graduate writing program in poetry while I was in law school just for the joy of it, so I've always kept my hand in it as a labor of love.

The great thing about my novel is that I was able to tell two important stories. One is the immigrant experience and coming-of-age experience of a Latina in a culture that is very strong in family values and in honoring your family and being true to them, but also there's a part of a society that expects young women to become independent and autonomous. How does a girl from a traditional culture navigate that without betraying either herself or her family?

Miami came from its roots in the old South. It was a quiet and sleepy town. There was always some degree of diversity, certainly in the African-American community that had been there a long time. There was, for example, the Bahamian culture that rose up in the Coconut Grove area, but in general, the city had some racial diversity but it had not been developed that much. The drainage of the Everglades was a process that took time and eventually freed up the land in south Florida so that as migration was occurring from both the north and the Cuban exodus, there was land available to be developed. So as that process escalated, Miami grew up really fast and became very international, very cosmopolitan. So I thought it was a really beautiful setting for the coming-of-age, multicultural experience such as that of Gabriela, the protagonist in my novel: a person who is forced to grow up quickly in circumstances that involve not just her own family but a larger society that itself is changing. So for me that was an interesting way of telling people about how Miami changed because nowadays people go down there and no one would even imagine that Miami was once this sort of sleepy place with canals and newly finished sidewalks that is now just so shiny and large and the gateway to commerce with Latin America, and just completely different.

For me, I had a very positive experience growing up in Miami. There were not that many Colombians. Now the Colombian community in Miami has just flourished. It's an enormous population down there. The Central Americans also grew in large numbers between the time of the Cuban diaspora to today, but when I was there I felt a lot of affinity. Now it could be that the part of Colombia where I'm from, Cartagena, is a coastal area that shares many similarities with other Caribbean cities in Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, so perhaps I was drawn and felt immediately at home with the food and the music and their way of speaking Spanish. Everything resonated with me, so I think I had a very wonderful Latinization process in that respect. I did not feel a sense of competition—which perhaps did exist, but it wasn't my experience.

The other story I wanted to tell in the novel, which draws on this other part of my life, is my career as an immigration attorney. I wanted to tell about the unique reality of lawful immigrants, people with green cards, who are allowed to be here and are not the undocumented people we hear about so much in the press. Yet they are subjected to many of the same rules that apply only to immigrants, so that they can lose their green cards easier than a US citizen who would never lose their right to be in the States. I felt that story was very much a part of my professional experience and has really broken my heart time and time again. I wanted to tell that story so that one could reflect on the morality of that kind of double standard and how it affects the immigrant's sense of whether or not he or she is included as an equal member of society.

In some respects, the culture is very welcoming, in the sense that we have this very noble tradition here of being what the Statue of Liberty embodies: a place where people can find refuge. And in Massachusetts, I also feel we have a really wonderful tradition in that respect. For instance, Senator [Edward] Kennedy was behind the [1980] US Refugee Act, which I am so proud of—that we were able to enact a law that really eliminated barriers, so that people would not be persecuted and they'd actually be able to get legal protection here. So I think on the one hand, that is a wonderful tradition, but I do believe that many of the laws have gone too far, such as those that involve the commission of crimes by immigrants who are lawfully here. And so, for example, in the novel, the father is losing his mind and he doesn't understand what's happening to him and his experience is very unpredictable, and so his conduct is also unpredictable. So when he gets into trouble with the law and potentially hurts someone, it raises the question: Should he be punished beyond whatever the ordinary criminal consequences are with exile? Loss of legal status? Loss of his home in the United States? To my mind, I think that's too harsh a penalty and it interferes with the ability of immigrants to have faith that they really are as welcome as the Statue of Liberty and the cultural message suggest. So it creates a sense that there's a double standard.

The organization I work for is a legal services institution—legal policy work, litigation, training, education materials—all aimed at bettering the lives of low-income people. And then my focus is on low-income immigrants in our state [Massachusetts]. So I will do all kinds of things, ranging from training public and government officials about the different kinds of immigration statuses and documents, to suing the government or an entity that is violating the rights of immigrants, to trying to persuade the government that a particular policy or interpretation that hurts low-income immigrants ought to be reconsidered or adapted or changed. So, for example, the Haitian earthquake victims were given temporary protected status. We are involved in efforts to make sure that the information about the details of that status is distributed to people in the Haitian community, including the clergy. So this is my way of giving back. There's nothing more rewarding than feeling like you're able to earn a livelihood by helping others who are in more difficult circumstances than yourself. I really believe that's the greatest way to have meaning—to feel that when I leave this world, I will have hopefully done something to have made it a little bit better for others.

As for the Arizona controversy, as a matter of law, I think that the litigation that has been filed by all the national groups against the law will ultimately prevail because the states are not supposed to be in the business of regulating immigration. But on a deeper level, I think it's very tragic because what it means is it sends a message—not just to undocumented people or, in this case, undocumented Latinos—that immigrants aren't welcome in Arizona, and that's very inhospitable and sad, and it can only hurt Arizona.

There are two key aspects to this. One is the mythology that immigrants are committing crimes, which is not borne out. Pretty much if you read any study, go to the American Immigration Council or online and find recent data specific to Arizona, which shows that immigrants actually commit lower levels of crime than the native born, and that immigrant crime rates go up the longer their time here in America because this is where they learned it. [She laughs at the irony.]

So protection against crime is not a valid, rational justification for it. As far as the federal government's abdication of its duty to act, I agree that the federal government should be enacting legislation to rationalize our immigration law system, which has been broken for a long time. The right way for the state to address that is to pass other kinds of resolutions, perhaps encouraging Congress to use its clout to influence its own leadership to act on immigration reforms rather than simply enact the laws themselves. And that would be an equally valid and democratic response that would be legal, and Arizona would not be shooting itself in the foot.

I have found that most immigrants want to work and make their own way, even though there is a public perception that they wish to take advantage of public benefits. That's counter to my own experience. My experience, from young people to old people, is that they want to work and need a legal avenue for doing so and getting work permission. I've recently been working a great deal with the students, the young people—we call them the “DREAMERS.” They're part of the movement to reform not only the entire immigration system but create a pathway for children who came here as undocumented kids brought here by their parents, perhaps as infants, and they have grown up here with essentially all the same aspirations as kids who are native born, but they get to a point in their lives where they can't get to college or can't get jobs because, lo and behold, they don't have legal documentation. It's called the DREAM Act, and it's pending in Congress.

It's a very promising piece of legislation that, if enacted, would allow young people who have lived here for a certain number of years, and who are planning to go into the service or to college, to access instate tuition in the state where they live and a path to obtain legal status. I'm on the board of directors for NILC [National Immigration Law Center], but I've had organizational clients who are involved in championing that legislation, so I have a lot to do with it and supporting them. And it's been very interesting: as I've been going around reading from my book or talking about it, some of these students have come to my readings and then talked to me afterward about their life experiences….

Anything that would be legislated by Congress would have to be a compromise of all the different interests in this area from all sides. But some of the elements that I think would rationalize the immigration laws so that they make more sense for the future are some sort of a legalization program for the people who have been here working hard, contributing to our society, paying taxes—who want the same thing we all want, which is security [and] to be able to bring our kids up right. And secondly, the numerical limitations on bringing relatives to the United States are just completely unrealistic. You shouldn't have waiting lists for a sibling to be reunited with his or her lawful relatives. The numbers are not logical anymore. They don't really fit with today's realities and the global nature of our society. And thirdly, this whole issue of fairness and proportion in how we treat people once they're here, like the one I've written about in my novel, about subjecting people to loss of their green cards many years later for very small crimes that, if committed by a citizen, would not incur such a harsh penalty.

I feel very blessed and lucky that my life has given me a lot of opportunity, and I'm thankful to both my parents for the sacrifices they made. I sometimes wonder what would have happened if I stayed in Cartagena. I have this cousin there who is my age, and she is a lawyer as well, but she was also a beauty queen a few years ago, and I was in Cartagena in January and she had taken a leave from her job to work in the mayor's office. It was amazing because as we talked about all the high-power issues of women who try to do too much, both personally and professionally, and we were both reflecting on how we would be the same wherever we were because we're trying to do more with our time than we could. So she's sort of my parallel half of me who went on to live there.

I first went back to Cartagena in college. It was really wonderful. Most of the older generation that was there on my father's side has died. All the Gomezes are deceased, but back then, there were more of them and a huge extended family. To even go to my grandparents' home the first time, I brought home [from there] a beautiful picture they hung in their house of my mother when she was maybe fifteen or sixteen in its original frame, and they gave it to me to bring back, and it was a really touching chance to be with them before they died.

I became a citizen as an adult, after 1996. I had to take the test, and I went to the American Red Cross in Boston, and there I was sitting with people who would ordinarily be my clients [laughs at the irony] and I was so embarrassed to get up. I didn't want anyone to feel bad, so I just made myself sit there until enough of the people in the group left before I took mine because I was embarrassed. A graduate from law school, a practicing attorney, working in immigration law, sitting in a room taking the test with everyone else—bizarre. And the sad thing is some of these folks around me had taken the test before and failed, and they're trying so hard, but adult learning is very different from learning as a kid.

How would I advise immigrants thinking of coming here? I've worked with a lot of persecution victims: people who have been tortured, held in detention for prolonged periods of time in clandestine jails. I've worked with people from Africa, Central America, all over the world, and for them, it's not really a choice. I think it's a question of survival. The human spirit has an instinct for survival that is beautiful and noble, and whatever people have to do in that situation to get out of their country to come here, I think they have to pursue it. I have a lot of sympathy for people who come here with false documents because it was the only way they could get out of that kind of situation, so for them it would be arrogant for me to even pretend to give someone in those circumstances any advice about how to do it.

But as far as wanting to come here to have a better life, I just salute them for their desire to do better for themselves and their children, and the main thing is to continue—even after they come here—to help those who are not in as good a situation and who are still adapting and try to give back some of what they've gotten.

It has not helped that we've been in a sustained period of economic difficulty. I've been touched by layoffs, and everybody in my community has been touched by layoffs. There have been very wide-ranging dramatic economic consequences over the last few years. And pro-immigrant and anti-immigrant attitudes fluctuate with the economy. So certainly that's affected the “promise” of the American Dream versus what's ultimately delivered. But to me, the deeper way that we've changed is that at the beginning of this nation's history, there were the people who first settled here, who were one group, and then the new groups gradually made their way in, so there was still a “They are they, and we are us” [mentality]—but today, increasingly, and not just in terms of immigrants but in terms of the descendants of slaves, we have a much more racially mixed population, so much more racial intermarriage when at one time there was prohibition on racial intermarriage, so now it's like, “We have met them, and they are us.” [She laughs.] So I think that over time, perhaps the biggest transformation is that what an immigrant is is almost a myth because now we've mixed in our families and in our blood all these immigrant communities, and so it's harder and harder to separate out one from another.

The “promise” is also affected by the back-and-forth of the other economies. I mean, we have this joke in Massachusetts: For a long time we had a lot of undocumented Brazilians in Massachusetts, and for some reason each community and ethnic group sort of carves out their own niche, whether they're taxi drivers or restaurant workers, but the Brazilians, for some reason, ended up largely in these cleaning companies, and they were very good entrepreneurs, but then the Brazilian economy began to turn around and get better while our economy was going down the tubes. So the joke was, “We're all losing our cleaning ladies.” [She laughs.] So it's a much more global world, and as things get better in one place, the outflow and the inflow get reversed.

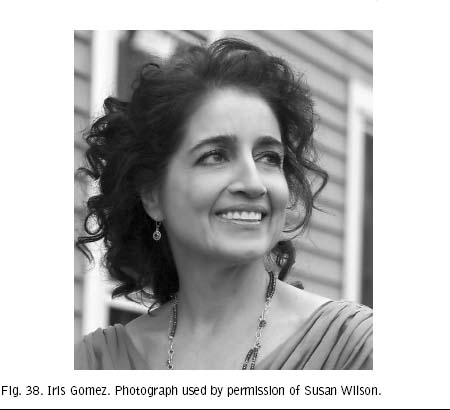

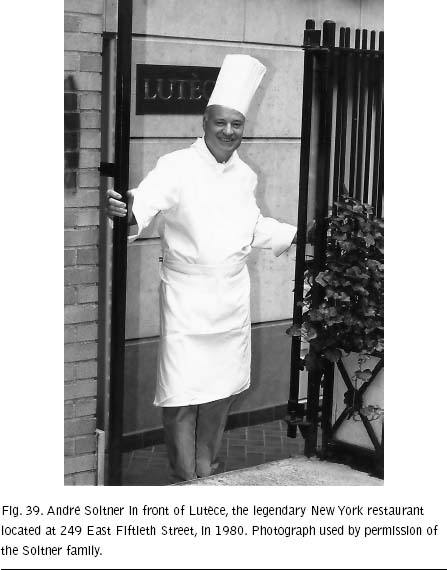

He grew up in a small Alsatian town on the French-German border. He came to America from Paris in 1961, recruited as a young chef for a new upscale French restaurant in New York, which he would later own. That restaurant turned out to be New York's legendary Lutèce, a four-star restaurant that in its day was the benchmark against which other restaurants were compared. It opened in 1961, and he operated it for more than thirty years. Julia Child once called Lutèce the best restaurant in the United States. Old guest books read like a “Who's Who in America.” Chef André cooked for them all, from regular folk to presidents and everyone in between. A chef's chef, he is the quintessential classically trained French chef, revered by his peers and the recipient of innumerable awards, including the prestigious Meilleurs Ouvriers de France, Officier du Mérite National, the Chevalier de L'Ordre du Mérite Agricole, the James Beard Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award, and the Légion d'Honneur, the highest decoration in France. The coauthor of The Lutèce Cookbook, he has served for more than twenty years as Délegué Général of the Master Chefs of France and more than fifteen years as the dean of classic studies for the French Culinary Institute in New York. A devoted husband, he has been married since 1962 to his wife, Simone, whom he met in Paris at a restaurant where she was a waitress and he was the chef. They never had children, but they worked together to create culinary magic of their own. “In Europe, we think America is the land of opportunity, and it is, but it doesn't come by itself,” he said in his thick Alsatian-German accent. “It's not free. The freedom's not free. You have to work for it. If somebody asked me if they should come, I would tell them if you're serious, if you're disciplined, and if you're willing to work—you don't fail.”

I was born in Alsace in a little town called Thann. It was a nice little town near the mountains, the Vosges, eastern France, about seven thousand people. I grew up there until the age of fourteen. School stopped at that age, and then you had to decide what you were going to do, and my first choice was to be a cabinetmaker because my father was a cabinetmaker. I also had an older brother who was a cabinetmaker, and my mother was completely against having two sons in the same business. I said it doesn't matter because I also loved to cook. I used to watch my mother cook and how she did tarts. There were no other chefs in the family, but my mom was a very good chef-housewife. She was an amateur chef. She inspired me and gave me the love for cooking.

In those days, to be a chef you had to do an apprenticeship. So I did an apprenticeship at the Hôtel du Parc in Mulhouse, which is about twenty miles from Thann, and I spent three years there in apprenticeship. We worked long hours, twelve- to fifteen-hour days there, six days a week, sometimes seven days a week, and were paid very little. My first year I made about six hundred francs, which was a little over a dollar a month, plus room and board, and the second year it was about two dollars and the third year about three dollars a month. And like most apprenticeships at that time, it was very tough—brutal, even.

For example, next to where I did my apprenticeship was a restaurant called Le Paon D'or, and the chef there punched the apprentice, knocked him out, threw him in a garbage can, and put the lid on! [He laughs.] The parents of the apprentice later took the chef to court, and the chef was banned from Alsace for ten years! Ironically, I later hired that apprentice when I was a chef in Paris at Chez Hansi. And the banned chef? I bumped into him years later in New York. I was walking home, and at Second Avenue and Fifty-Fourth Street, there was a French restaurant, and the back door of the kitchen was open, and being a chef, if we see a kitchen we look in, so I look in, and who do I see but him. I said, “What are you doing here?” and he said, “André, what are you doing here?”

Where I worked, they put you pretty far from the head chef. His name was Rene Simon. He was my first chef, and he was tough, too. One time he slapped an apprentice, who fell back on a pile of coal—in those days we cooked on coal stoves—and he grabbed him by the shirt, dragged him across the kitchen floor, opened the door, and threw him out. The next day, seven a.m.—that's when we started work—the boy was there, he was at work, because we admired the chef. He was a very good chef. And believe it or not, he was a nice man, too, but he was a disciplinarian, and so to be an apprentice, sometimes it was brutal. We worked sometimes from seven a.m. to two a.m. the next morning without sitting down. He was very tough, but I loved him. [He laughs.), I was fourteen and a half when I started. I did three years under Rene Simon, and he was my mentor. He taught me what I know about cooking, and he also gave me the love for cooking. He's really the chef I admire the most in my whole career because he was very talented.

After my apprenticeship, I took a certification exam all young chefs had to take to become a professional cook in France, and from there on, like most other chefs, I went from one city to another and from one restaurant to another. I started in Mulhouse and from there went to work at the Hotel Royale in Deauville, big hotel, maybe twenty-five cooks; the Palace Hotel in Pontresina, Switzerland; and the Hotel Acker in Wildhaus, Switzerland, near Zurich. I came back to France for my military service. I was drafted into the Alpine troops in the French Alps. I didn't tell them I was a cook; otherwise they would have put me in the kitchen, and I love to ski. I was always a skier. Then, after a few months, I was sent to Tunisia, to North Africa, because of the troubles between Tunisia and Algeria and France. In the Alpine troops, we were in the mountains in Tunisia. We were there for nine months until I was released in April 1955.

My idea then was to go to Paris. For a young chef, Paris was it because there were lots of jobs, many restaurants. I began working at Chez Hansi, an Alsatian restaurant, as the “round man.” The restaurant was open every day, six days a week, so I changed posts and replaced the cook who had the day off. I was chef de partie, which means you take care of one part of the kitchen. So one day I might do sauces, another day vegetables [and so on], so I had the full experience there. After a few years I became sous chef, and a few years later, I became head chef. At the end of my time there, I had fourteen chefs and two pastry chefs working under me.

I was there for six years, but if you stay in the one place too long that's not good, and then I had an opportunity to come to this country. I played Ping-Pong® in a chef's club. My pastry chef and another pastry chef, we played together. And the other pastry chef had been to America and worked at Idlewild Airport [now Kennedy Airport] as a chef for a man in the airline catering business. His name was André Surmain, who planned to open a restaurant, a very high-class restaurant, in New York, and he was looking for a young chef. This pastry chef told Surmain about me.

So Surmain flew to Paris and had dinner at the restaurant where I was working. After dinner, he asked for me and told me about his plans for Lutèce [the name comes from “Lutetia,” the ancient name of Paris] and said, “Are you interested in coming to America?”

At first I was a little surprised. He promised me a lot of things and convinced me to come. But I was already a little brainwashed because when I was a child my grandfather came here earlier. He came to America, one of two boys and two girls. They came through Ellis Island around 1900. He was a baker. The two boys were bakers. They came to New York and then went west to Nevada and California. So he told me all the time about Nevada and California, and so finally I said to Mr. Surmain, “OK, let's try it. I am willing to come.” So I went to the American consulate in Paris, and I left two hours later with the green card; people don't believe me anymore because now to get a green card is so difficult, but in ‘61 the quota for France was never full, so it was easy.

A few months later, I came to New York. I was thinking I would come for a year or two, learn English, and go back. That was my plan. I really wanted to see how people lived here. It was not for the money because my salary in Paris was the same that he offered me in New York: ninety-five dollars a month. But, you know, I was single, I was just twenty-eight, and he said if things worked out he would make me a partner, and I thought, OK, let's see. What did I have to lose? I had met my wife, Simone, by then. She was a waitress at Chez Hansi, and I was dating her, but I came here single. I said, “OK, if I like it there I will come back for her. Then maybe we will get married and she will join me.” And that's eventually what we did. She came about a year and a half after me.

So I flew to New York, and at first you feel a little lost if you don't know anybody. But the next day I started my job, and we opened the restaurant at 249 East Fiftieth Street. Most of the employees were French, so I got along very quickly. And right away, I must say I liked it because the people who came in, American people, they were different than the clients in France. In France they could be a little snobby, you know, but here I noticed right away a big difference in the relationship with the customers, and I liked it very much.

My biggest problem was I didn't speak English, but I am Alsatian so I spoke both languages, French and German, so it helped me a lot, especially for the food buying because many suppliers spoke German. So I had a little difficulty with the language at first, but I didn't have time to go to school, so I just picked it up as I went along.

We opened Lutèce in 1961, with Surmain as the owner and me as the chef. But it was not well known then, and the big problem was that Surmain charged high prices right away. We were very expensive. We were the most expensive restaurant in New York, maybe the most expensive in the United States at that time, and that hurt us very much, and we didn't do much business. And then little by little we did better, but after a year and a half I felt it wasn't quite working out as I had hoped. We just had different philosophies, and he also had promised many things, so I said to Surmain, my boss, “Look, this is not really going as I hoped. It's time for me to go back,” and he said, “No, no, no, André. You cannot go now! The restaurant is doing better, much better now than a year ago. If you stay, I will take you as a partner.”

I said, “You told me that in Paris two years ago and that never happened.” He said, “No, I mean it. You stay and we go into partnership.”

He sold me 30 percent of the restaurant. We were partners until 1972, when he decided to go back to Europe and I bought his shares. Our partnership did not go too well. It did OK, but he didn't work hard. And I believe in working hard and always being there, and he was away all the time. He sailed to Europe, and he had a farm in Majorca, Spain. So I said, “Yes, I have 30 percent but I'm doing all the work.” My wife worked the front of the restaurant—taking reservations, greeting customers—while I worked the back, and we decided it wasn't fair and decided to leave, but Surmain said, “No, no, no. I'm fed up with this business. I'm burned out! I don't want it anymore. I leave!”

I said, “OK, but if you leave, you leave.” So we drew up papers. It took about nine months to find a way, you know? Because I didn't have the money to buy his shares, and then we found a way to do it, and he left and I bought him out in 1972.

When he left I thought I could do it because I was in the kitchen; I was not in the dining room. I was the chef, but I was a little scared and shy. This was a huge thing for me and I thought I could do it, but after two or three months my accountant came. He came every two weeks, and he said, “Look, André, it doesn't look good. You don't have enough cash flow. You have to pay staff. You have to pay the suppliers and everything. If you don't bring money in, the company will go under. You cannot survive.”

I said, “What do I do?”

“You have to look for money.”

This was the beginning of 1973. It was wintertime. I put a coat on over my chef's jacket and went to Bankers Trust on Fifty-Second Street and Third Avenue. I went to the teller, and the teller asked, “How can I help you?”

I said, “I need money.” He was smiling a little bit and said, “Go to the gentleman over there in the office and talk to him.”

So I did. I told him, “I have a restaurant and I don't have the necessary capital,” and he said, “How much do you need?” Well, I was a cook, you know? I was not a businessman. I said, “I don't know. I think it was $40,000.” [He smiles.) Remember, $40,000 in 1972 was a lot of money. He made me fill out a few papers, but he did not ask me much. In France, they would have asked me everything, including when my grandfather was born [laughs] and the last time I went to the dentist. So he made a few calculations, drew up a few papers, and I signed everything and left the bank with $40,000 on the spot. They put it in my account. Just like that. Today when I think back, it's just unbelievable, you know? And I never saw the banker again.

Soon after, Malcolm Forbes—he was a customer, and I always took to him a little bit, and one day he came in and said to me, “André, I heard André Surmain left?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “André, if you need money—whatever you need, you tell me, I'll give it to you.” He didn't say “I'll lend it to you,” he said, “I give it to you! And if one day you can pay me back, you pay me back,” but I never took him up on his offer because in the meantime the bank gave me this $40,000. When Malcolm Forbes passed away, his son Steve called me about two or three months later. Steve was also a customer. He said, “André, you're in my father's will.” [He laughs.] As a gesture, I guess, Malcolm Forbes put $1,000 in his will for me!

Around this time, I became a citizen, but in my mind I was already a citizen. When I came here, I felt good right away. I already had a green card, so I didn't think going for my citizenship was important. But my lawyer said, “Look, André, you're not a citizen. You have a liquor license; if, God forbid, something should happen, you could lose your license. You should be a citizen.” But who really pushed me was then governor of New York Hugh Carey. He came to eat many times—his office was on the same block as Lutèce—and he said something once to me, and I said I wasn't a citizen yet, and he said, “You're not a citizen? I'll sponsor you.” So I called my lawyer and said I wanted to be a citizen, and I went downtown to take the test for citizenship like everybody else….

Before Surmain left, we never did one hundred covers. He always said, “If we make one hundred covers I'll pay for the champagne,” but we never did it. After he left, we changed the ambience of the restaurant. He was a little snobbish, you know. He snubbed the customer a little bit if he didn't like the way they looked or dressed, and we changed that and made it more comfortable. We quickly went to 120 covers. We were still expensive, but we were in the same price range as a few other French restaurants in New York—Le Cirque, Le Caravelle, Le Cygne, Le Grenouille. We cooked traditional French cuisine, and I would go from table to table and personally greet the customers, make them feel welcome, and if I had good relationship with a customer, I always had one or two Alsatian dishes that were off-menu, like my potato tart. When I grew up my mother did what's called tarte aux pommes de terre or potato pie that I loved. It's my favorite dish, and it's very simple to make. It's hard-boiled eggs, potatoes, and bacon done in a pastry—very inexpensive to make, so I could not put it on the menu and justify charging thirty dollars for lunch.

We were rated four stars in the New York Times, and that gives you a big push. We once were in Playboy. We were rated the number-one restaurant in America. And for two years after that people came from all over—from Kalamazoo, you name it.

If there was one customer, President Nixon was one of the great guys for us. He was so gracious. Always so nice. He stopped in the kitchen; he talked baseball or football with my guys. He would come with a large party, and I would say, “Mr. President, what would you like?” And he would say, “Just order for me like you usually do.” And there was once an article in Newsweek about Nixon, and they were talking about dining, and Nixon was quoted as saying, “Our main favorite is Lutèce because we like owner André Soltner so much—and now and then we go to Le Cirque.” When this article came out, it was a huge thing for us [makes grand gesture]. We refused people. Unbelievable! That was a real boon!

I helped bring Alsatian wine here to America because I used to serve it at Lutèce, and to thank me, the town in Alsace where I was born put this memorial in the vineyard. There was a ceremony with the mayor and a senator to thank me, and I thought, what could I do for them? And then I had an idea. President Nixon liked Alsatian wine very much, and I thought if he could say something about how much he likes this wine.…So one day he came, party of eight. I said to Nixon, “You know, Mr. President, the wine you like, it would be nice if you could give me a few words,” and he said, “No problem, no problem.”

Then I said, “Should I call your secretary to tell her?”

He looked at me and said, “You think I'm going to forget?” [He laughs.] I said, “No, no.” What a smart guy he was! He gave me a letter about how much he liked the wine, and at this ceremony with the mayor and the senator, I gave them the letter from President Nixon. They have it now at the town hall there….

To run a successful restaurant, you must be serious and you must be present. I was always at the restaurant. If I wasn't there, I would not open the restaurant, and that's it—you cannot cut corners. Same is true with the customers. They look for value. They know you will make some money, and they understand that, but they want value. If you say “fresh” to a customer, you have to be serious, and if it's not 100 percent fresh, don't serve it.

We rarely had staff meetings. I asked from my dining room staff that they were clean, welcoming to customers, not snobbish French [smiles]—that was a big one—and to stay serious. My kitchen staff was serious, no drinking, clean, and on time. We had discipline, you know? I incorporated many of the things I learned from Rene Simon. His rule was if you start at seven a.m., then it's seven a.m., not five after seven. I had the same rules. And I respected my staff very much and expected that they respect me the same. There were forty-two staff. That's a lot, and that's why a restaurant has to be profitable.

Today you have Jean-Georges Vongerichten, Daniel Boulud, Thomas Keller—it's completely different now because the business is different. You see these guys and they have four, five, six restaurants—they're real businesspeople. I had one restaurant, and I never considered myself a businessman. I considered myself a craftsman, a cook. But they came along because it was a different time. They became businessmen. They are still chefs—they are good chefs; otherwise they would not be where they are—but to be in the business now you need backers, investors. To open a restaurant in Hong Kong or Las Vegas for me, at my time, it was not so. I had offers, but it was not my time.

I once had Japanese people approach me. It was the beginning of going bigger, and they came to me about opening Lutèce in Japan, and I said, “I'm not interested.” They said, “André, you owe us the courtesy to listen to us.” I said, “OK,” but in my heart I was always a chef, a cook, you know? So we had a meeting in an office, a big building, and there were five, six guys there, and they said, “We would like to open seven Lutèces in Japan.” And I said, “I'm not interested. I have a restaurant.” They said, “Keep your restaurant.” I said, “What do you want from me exactly?” They said, “We want you to be in Japan three months a year….” This was around 1990, and they said, “But the rest of time you can stay with your Lutèce in New York—it's yours, not ours, and that's basically our deal.”

I said, “Let me think about it,” and I came home and told Simone because my wife was always with me in business, and I said to myself, “What will I do in Japan for three months?” I was thinking maybe I meet a Japanese girl and I wind up getting divorced. I called them back and said, “Forget it.”

We decided to sell the restaurant in 1994 because it's a very tough walk, you know? We started to get a little tired, especially for my wife; she was very much involved. And the owner of Ark Restaurants came once for dinner, and he told me that he might be interested in buying Lutèce—and Ark was a big company; they had something like thirty restaurants—and asked me if I would sell. And I said, “Well, everything is for sale,” and I was sixty-three years old then, and I said to my wife, “What do you think?” We knew we had to stop one day.

Ark bought the restaurant, not the building. I still own the building. I gave Ark a fifteen-year lease, but after nine years, they couldn't make it go and closed in 2004. They couldn't make it, I think, because it was a very personal restaurant. It was Lutèce, but it was André Soltner. It was not personal anymore. People think with a restaurant you make millions, but to make money in a restaurant is not an easy thing. You have to be there. You have to watch it and control it, and they didn't have that. So they didn't make money. A restaurant has to be profitable. If you don't make money, you go under, and it's not the money you put in your pocket, but to pay your suppliers right away and keep your staff. You can tell them, “You're part of the family,” but that works for six months, so they also have to find their advantage, so you have to pay them a little more and things like that. To make money in a restaurant, you have to be there, and you have to watch everything.…

And whatever happens, be humble. If somebody is successful and they get a big head, it disappoints me very much. You know, André Surmain, we are still friends—he'll be ninety soon—but he was a bit of a snob, so when I wanted to bring him down to reality, I always said, “André, we are soup merchants, don't forget that. We are not ambassadors. We make soup, and we sell soup.” And that's very important, especially now, in an era where chefs are very recognized and they are suddenly stars, celebrities, but it should not go to your head. Stay humble!

And be serious, and when I say serious, I mean disciplined and not to think that you come to America and America is waiting for you. America is not waiting for you. Put that in your head. You have to earn it—otherwise you don't make it—and it's not easy. In Europe, we think America is the land of opportunity, and it is, but it doesn't come by itself. It's not free. The freedom's not free. You have to work for it. If somebody asked me if they should come, I would tell them if you're serious, if you're disciplined, and if you're willing to work—you don't fail.

In Europe, when you say you are an immigrant, it means you are maybe a little lower than all the others and I don't want to be nice to you, but I must say that here you don't have that feeling. If you don't speak English the way you should, nobody looks at you. Everybody thinks it is normal, and that's really what I like the most here. You don't have any complex to be an immigrant. In France, I remember the Italians or Spanish people, they were accepted too, but they were a little not the same level, really. But here it isn't so, and that is really the nice part here. I really feel at home here, I really do.

In the past, we went back to France normally every two years, and for many years now we've had a house in the Catskills, which I like very much because the Catskills looks a little like Vosges, from where I come, the same type of mountains. So we have a house there at Hunter Mountain, and there are at least ten other chefs who also have houses. So on Sundays we cook and eat together. Restaurant people are like circus people because we are in a business where we have a little odder hours than others. We try out our new recipes and things like that. We do our own cider, and we ski. We have our annual chef's ski race that we've been doing for more than thirty years…. But these days my wife and I go on a lot of cruises. I go as the guest chef. We go once a year; some years two or three times. Recently we went on a cruise and the son of Nikita Khrushchev was the guest speaker for politics, Sergei Khrushchev. I was for cooking. He was for politics. We've gone on over thirty-four cruises….

My fondest memory is that I'm happily married almost fifty years now and that we're still together. We had success, but it didn't go to our heads. No children, though. That's my disappointment. C'est la vie. You know, you cannot change some things.

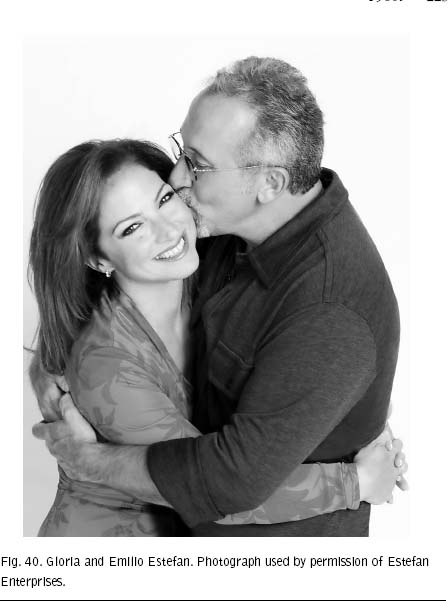

He came from an affluent Cuban family. When he was fourteen years old he went with his father from Cuba to Spain, leaving behind his older brother and his mother, who stayed to look after her father, and spent eighteen months in Spain before coming to Miami alone to live with his aunt and uncle. He went on to become the producer/husband of singer Gloria Estefan, one of the top-selling artists of all time, with more than one hundred million albums sold and seven Grammy Awards to her credit. She emigratedfrom Cuba with her mother when she was two years old and settled in Miami, where she and Emilio later met. Today, Emilio is a nineteentime Grammy Award–winning producer, songwriter, and founder of Estefan Enterprises, which encompasses everything from music publishing, television, film production, and artist management to hotels, restaurants, and real estate. “I would advise others to have respect for a country that gives you an opportunity,” he said. “It doesn't matter where you come from; we all cry for this country.”

I was born in Cuba in a town called Santiago de Cuba, which is all the way on the other side of the island from Havana. When I was a kid, Castro took power, and the whole thing I remember in the house was conversations about being in a Communist country because they were taking everything away, and that made the whole difference for me. I mean, even when I was ten years old I heard my mom and my dad talking through the doors. My mom was crying, saying if I was going to stay in a Communist country, what will happen when I reach military age, which was fifteen, and I was eleven years old then, and I remember that I cried all night.

In the morning I told my mom, “I have to leave Cuba.”

And she said, “Well, how are you going to leave Cuba? We'll probably never see you again.”

Then when I was fourteen, I said, “I want to leave with my dad.” Because he was talking of leaving.

She said, “Well, you know something, I'm gonna let you do it because I feel [pauses] don't do it for me, do it for you. I think it's a great thing that you'll be able to live and realize the American Dream and live in a free country.”

So I made the decision to leave when I was eleven years old, but I left when I was fourteen.

The life there when I was a kid—it was a country that was converted to a Communist country, so people lived in fear. They were arresting a lot of people. I remember when Castro changed the money into Cuban dollars. I never met Castro, although he used to live really close to my house. He went to the same school as me when he was a kid. The same school in Santiago. He was born in Santiago de Cuba.

I remember one day they [Castro's men] came to my house, and they went to my mom and my dad's room, and he used to have a safe inside the room. They took him to open the safe, and he got nervous, and they took the [whole] family to the patio with machine guns. They thought that we were hiding something, that my father was hiding dollars, especially dollars, because they were looking for dollars. Then they used some dynamite and blew the whole safe—and to me all those elements are what convinced me to make the decision to leave Cuba. And not only me—I didn't want the rest of my family to live in a country like that.

My father used to own a factory, a clothing factory. We were not really millionaires, but we were well off. And my father was a poker player, a professional poker player. He won the lottery twenty-seven times in his life! He was a very lucky guy. And he was always up and down; sometimes he was filthy with money, and sometimes he was totally broke. He played at the hotels. He used to play at all the casinos in Cuba. I mean, he loved to play. Sort of like [in] the movie Havana. My mom took care of the home, took care of us. I had one older brother.

To me, the decision to come to America was not about money. I always looked at the United States as a place that represented freedom, that you have the right to free expression, have the right to any dream. But to me, more than anything else as a kid, I was afraid to live in a Communist country, and I saw what my mom and my dad were going through and my whole family.

When we used to have dinner or lunch, we had to talk quietly because they were afraid somebody was listening to them. So my whole motivation was really fear—fear that I should live in a country where I am afraid to talk or have my opinion. I saw everything that was happening with my family, and then my aunt was arrested because her son escaped to an embassy when he was around twenty-one. They came the next day to her house and said that she probably knew that he was escaping from Cuba. And she said, “I didn't know that.”

She really didn't know! They put her in jail for almost fifteen years just to punish her. Fifteen years in jail! She served the time, then she came to Miami, and then she died. I mean, it was amazing. And so being a kid and seeing all these elements and the pain that I saw with my family, I said, “I have to leave.” Even though it was the hardest decision I made in my whole life because I realized I may never see my mom or my brother again for the rest of my life.

The day I left, I remember when it was time to say good-bye to my grandfather and the rest of my family, I knew I was never going to see them again. But at the same time I remember going to the airport and holding my mom and my brother and then getting onto the plane to go to Spain. We went to Spain because that was the only way out. At the time, there was no direct flight to the States. And my mom was of Spanish descent, so they gave us a visa to Spain.

I cried all the way from Cuba to Spain. My dad and I flew to Madrid.

We got to Madrid at night, and when we got out of the plane and we started walking, I remember feeling cold and how the cold weather was so different for me. I remember it was late at night at the airport and the airport was empty. But I saw two priests at the end of a corridor, and I was crying, and my dad told me, “Everything will be OK. Just take your time. Things will get better for the family.”

We were almost homeless in Spain. When we came they helped us, but we had to go and eat in a church because we didn't have enough money to eat in a restaurant or to buy food. My father couldn't take any money out of the country. When you leave Cuba, you're not allowed to take anything—not even one penny. You can take just what you're wearing and that's it. So some relatives and friends in Miami sent us money to help us, and my dad and I found a small apartment. We had left behind my older brother and mom and her father, my grandfather.

The idea was that my dad and I were going to go to the United States and bring my mother and my brother later. My mother said, “I don't want to leave until my father passes away,” because her father was still alive. He was too old. He didn't want to leave home, leave Cuba. Later on, after we got to Miami, I told her, “Listen, you did what you have to do, but my dad and me—we need you here.” It was a hard decision because my older brother was at the military age, so he couldn't leave.

We were in Spain for eighteen months before I got a student visa to come to the United States. My father was not able to come with me right away, so I went alone. My aunt in Miami sent money for my ticket. The plan was for me to go ahead, get to America, and then petition for my father because as a child, a minor, you were given priority to be reunited with the parent. I think we also had refugee status, although we never collected money or anything. I flew to New York and then took a connecting flight to Miami, and I called my uncle and said, “Here I am!” I was fifteen years old by then. My uncle came to pick me up at the airport, and we went to see my aunt and the rest of the family.

At that time, my aunt and uncle had fourteen kids in their house, and all of military age, because when we lived in Cuba, if you were fifteen years old you were not allowed to leave the country. So every family would try to get their kids out before they were fifteen and make sure they were safe. I was so happy to see them. My dad and I lived with my aunt and uncle for many years in Miami, and then after my grandfather died in Cuba, my mom came through Mexico to the States.

In Miami, I remember we used to go to Freedom Tower [a historic 1925 landmark building that serves as a memorial to Cuban immigration to America] to collect food because they gave out food once a month, oatmeal and cheese and many different things for the Cuban refugees….

I went to school in Miami, but I needed to work. My goal was to get money to bring my family here to America. So I went to school, and I went and applied at Bacardi [Rum]. I knew the family. I grew up with the Bacardi family in Cuba. We went to the same school. And they said, “You're a minor, so you have to get a special permit.” So I asked for a special permit, and I worked at Bacardi as an office boy.

I also convinced my uncle to get me an accordion because I wanted to make money. It was the only instrument I knew how to play. So we went and got an accordion for $177. We got home, and my aunt told me, “What are you doing? We don't have money to pay even rent. How are you going to pay for this accordion?”

I said, “Don't worry. I'm going to play, and I'm going to make money with this.” So I went and played with this guy who used to play the violin, and we would play for tips in a restaurant. It was a really old-time famous Italian restaurant in Biscayne. Sometimes we collected five dollars, ten dollars, fifty dollars; it all depended on the crowds that night. After school, I used to change in the car, and I used to go and play the accordion for tips.

One day the Bacardi family was having a party and they needed a band, and I knew all the songs from Cuba on the accordion, so I brought a percussionist and a bass player and we played all the Cuban songs. We were a big hit. So they used to call me and say, “Come and play at the party,” so I used to go and play the accordion, and that's how the whole Miami Sound Machine got started.

I met Gloria when she was rehearsing in church as part of a group, and I went and listened to them, and I saw Gloria and I said hello. It was a nice group. And then like three months later, I was playing at a wedding and Gloria passed by, and I said, “Oh, you're the one who was singing [in church]. Please come and sing a song with us.” And I heard the sound, the Latin music, and I thought this would be a great sound for performance.

So she came to the party and I asked her to perform at the wedding. And she came and I loved the whole sound, and I said, “This is really great! We should do something together. If you want to perform, we can do it this weekend.” And she came with her grandmother, her mother, and her sister. Gloria was very young at the time. She was only about seventeen, eighteen years old. She was studying psychology at the University of Miami. She sang at church, but not professionally; she was just a kid.

Gloria and I had a lot in common. We were both born in Cuba. We loved music, family, and both of us when we were young were separated for extended periods of time from loved ones. For me it was my mother; for her it was her father. He was a motorcycle policeman. He once was a motorcycle escort for the wife of Batista [Cuba's president, Fulgencio Batista], before Castro. Her mother was a kindergarten teacher, and they lived a comfortable life in Havana. But when Castro came to power [January 1959], Gloria's parents decided to leave the country until things quieted down. Gloria was two years old at the time. Her mother flew into exile in Miami with Gloria. Castro had not yet closed all the flights from Cuba to the United States. Her father joined them a month later. They had very little money, spoke almost no English, and settled into a Cuban neighborhood near the Orange Bowl [now Sun Life Stadium] in Miami [Gardens]. Then her father went off to train for a secret mission, which was the failed Bay of Pigs invasion [April 1961], and was taken prisoner by Castro's forces. He was in a Cuban jail with hundreds of others for nearly two years. Gloria was too young to understand what was going on, but if she asked, her mother would say, “He's away working on a farm….”

As a singer, what I saw in Gloria was something that was different. She was bilingual. She spoke English, Spanish, and French fluently. I loved her voice and the way she sang, and I said, “Listen, I would love to bring you into the group.” I wanted to call it Miami Sound because I felt it was the sound coming out of Miami at the time that fused American and Cuban music in a unique blend. And then that started the whole Miami Sound Machine in 1976, and we recorded the first album, and it became huge. It was number one almost all over the world.

I went back to Cuba when my brother's wife died. This was about thirty years ago, 1980. She committed suicide and left him stuck there with the two kids. And Castro at the time was allowing anybody to leave, and you could bring your family to the States and get a boat and bring them back and the States approved that, so I went in a boat. I never went in a boat before, so I got lost.

When I got to Cuba, they told me my boat was too small. So I called my brother and said, “Listen, I'm in Cuba but I'm not allowed to take you because the boat that we came in is too small,” and he said, “Forget about me—don't even care about me no more,” and he hung up the phone. And I got really worried, and I knew this was the only chance to get him out of Cuba. So I went back to the States, and I had a good friend in Costa Rica who knew somebody who was close to the president, and they helped me. It took a lot of work, but we got visas for him and his kids to go to Costa Rica, and the Cuban government finally let him go. They gave him a hard time. And then he got to Costa Rica and applied to the US consulate and he came to the States.

I would advise others to have respect for a country that gives you an opportunity. It doesn't matter where you come from; we all cry for this country. We feel that we belong in a way, even though we were not born in this country. We feel that we have an honor, that we're welcome, that we're realizing the American Dream. In this country you can have opinions, different opinions, and anything can come true. At the same time, like I always tell people, to become an immigrant or a citizen of a country, you always have to have respect for the country, and that's what me and Gloria have felt all our lives. We never take our citizenship for granted. We appreciate what we have. We always want to give back to the country.

1960:

1960: