Immigration in this decade was heavily influenced by the Vietnam War. The US withdrawal from South Vietnam in 1975 and the subsequent Communist takeover of South Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos triggered a new wave of refugees, many of whom spent years in Asian refugee camps waiting to get into the United States. The number of legal immigrants had now steadily increased for three straight decades: from 2.5 million in the 1950s, to 3.22 million in the 1960s, to 4.25 million in the 1970s.

KEY HISTORIC EVENTS

MIGRATION FLOWS

Total legal US immigration in 1970s: 4.25 million

Top ten emigration countries in this decade: Mexico (621,218), Philippines (337,726), Cuba (256,497), Korea (241,192), Canada and Newfoundland (179,267), Italy (150,031), India (147,997), Dominican Republic (139,249), United Kingdom (133,218), Jamaica (130,226)

(See appendix for the complete list of countries.)

FAMOUS IMMIGRANTS

Immigrants who came to America in this decade, and who would later become famous, include:

John Lennon, England, 1971, Beatle

Colin Firth, England, 1971, actor

Isabella Rossellini, Italy, 1971, actress

Jon Secada, Cuba, 1971, singer-songwriter

James Cameron, Canada, 1971, film producer/director

Rudolf Nureyev, Soviet Union, 1972, dancer

Wolfgang Puck, Austria, 1973, chef

Alex Trebek, Canada, 1973, game show host

Patrick Ewing, Jamaica, 1973, basketball player

Mikhail Baryshnikov, Latvia, 1974, dancer

Sir Anthony Hopkins, Wales, 1974, actor

Dan Aykroyd, Canada, 1975, actor/comedian

Martina Navratilova, Czechoslovakia, 1975, tennis champion

Iman Abdulmajid (“Iman”), Somalia, 1975, model

Agostino “Dino” De Laurentiis, Italy, 1976, film director

Jerry Yang, Taiwan, 1978, cofounder of Yahoo!

Joaquin Phoenix, Puerto Rico, 1978, actor

Michael J. Fox, Canada, 1979, actor

Ang Lee, Taiwan, 1979, film producer

Sergey Brin, Soviet Union, 1979, cofounder of Google

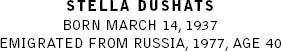

She is from St. Petersburg, Russia, where she was a teacher and her husband was an accomplished and well-known architect. Anti-Semitism drove them, along with their sixteen-year-old daughter, to America to start over in search of a better life. They settled in San Jose, California. She became a bookkeeper. He got an entry-level job at a San Francisco architectural firm and worked his way up from there. She is the first cousin of famous Ellis Island immigrant Isabel Belarsky, who immigrated to America through Ellis Island in 1930 when she was ten years old and was interviewed in my previous book, Ellis Island Interviews: In Their Own Words. Isabel is the daughter of Sidor Belarsky, the famed Yiddish singer and conductor, whose music was featured in the Coen Brothers movie A Serious Man. Sidor and Stella's mother were brother and sister. “We knew if we work hard we will get everything,” Stella said in her thick Russian accent. “But in Russia it didn't matter. You could work hard and get nothing, and if you were Jewish, you got less than nothing. You felt like a second-class citizen.”

We came to America by plane from St. Petersburg to Vienna, Austria. We stayed there for a week and then flew to Rome. We stayed there for nearly four months, and then on April 13, 1977, we flew from Rome to New York and then to San Jose, California. The Jewish Federation of San Jose took responsibility for us.

We left Russia because of problems with being Jewish at that time. It was very difficult to live there and to build any future for my daughter. A lot of Russian Jews emigrated at that time. People would point at you as a Jew. And my daughter, for example, she was the only Jewish girl in her classroom, and everyone would taunt her and point at her: “You are Jew! You are killer!” They said Jews in Israel are killers because they killed the people to keep their land. And she would come home crying, and the teachers were watching that and doing nothing. For example, for me, I was a teacher; I had to be there and listen to what the students had been saying and talking about, and there was not much I could do. My daughter, Galina, was sixteen when we left Russia.

I was a teacher in chemistry and biology in high school. I was married. My husband passed away three and a half years ago after forty-seven years of marriage. He passed away the day after our forty-seventh wedding anniversary. We married on December 25, and he passed away on December 26. He was an architect. He was involved in the reconstruction of the main part of St. Petersburg. We had already built our careers because we finished university and had been working. But we didn't know what would happen with our daughter because only 3 percent of young Jewish people could go to university. And the whole situation with Jewish people in Russia was you never knew what could happen. In the street, you could be abused because you are Jew; you could be told in your face, “You are dirty Jew.” All the time we were told and reminded that we are Jews and that in Israel they are killers and you are part of these people, that kind of stuff. Nobody tortured us, but you could be beaten on the street and it wouldn't be by the government, but by regular people. Even now, people said when Stalin passed away [1953], it was exactly the time when all the Jewish people from all the cities were supposed to be transferred somewhere—who knows where? All the trains were ready to take all the Jewish people together to transfer to Siberia or somewhere east. There are a lot of books which are now available to the public to read about what Stalin's plan was….

Our life in Russia was a hardworking life. Put it this way: I was a teacher and my husband worked many hours each day. We didn't starve. You know, we are educated people. We like theater, we like music, but moneywise, we didn't make so much. We didn't travel because it wasn't allowed for us to travel to different countries. But we did go in summertime to the countryside sometimes and traveled to the Baltic countries, which were close to us, north of St. Petersburg.

I had some friends who were in America, and they gave information about us to the Jewish Federation. There were a lot of Jewish organizations in communities in different states and different cities that had been taking care of Jews, such as the one headquartered in New York called the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society [HIAS]. They had actually been taking care of us, and there was an office in Rome that had been helping us, and they distributed immigrants to different states and different cities, and that's how we came to San Jose.

We flew to New York, into JFK, and stayed overnight in a hotel before we continued on to San Jose. My cousin Isabel and her mom, Clarunia, found out from HIAS where we were staying, and they met us there at this little hotel in New York. We were sitting there in the lobby crying and talking the whole night, and the next morning we flew to San Jose. At that point, Sidor, Isabel's father, had passed away two years earlier, so Isabel and Clarunia were living together in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, and I guess we could have gone there. But they [HIAS] told us it would be much better if we go to California—more opportunity, especially for Galina's education because college in California was free. They said it would be better to build our life in California, and they were right because we were very happy here. They said it was too crowded in Brooklyn, that in San Jose, there weren't so many immigrants, so we could have more attention, more help for our first few months than we would in Brooklyn. We also had a friend who came to San Jose a year before us, and HIAS had an office here.

It wasn't the same process as the people who came through Ellis Island. This was organized before we left—an organized immigration process. We had a visa just to get here, and then as soon as we came, HIAS had wonderful volunteers here. I'm still friends with them. And they took care of us, and they took us to the office to get permission for work. It was not a green card. We would not get our green cards for another couple of years, but we still had the permission to live here and to work here.

We lived in an apartment. HIAS took care of everything. They paid the rent on the apartment. But I remember being very scared because we didn't know English. We didn't have anyone here. Sometimes when the telephone rang we were scared to pick it up because we didn't understand English. I learned a little bit back in Russia many years ago, but our English was very limited. For example, when my husband had to make a speech the first morning at his new job, he said, “Thank you, us, that we came to you.” [She laughs.] So I took English classes. There were forty-five people in a class, but [it was] only two hours a week.

My daughter didn't know any English. She started English at school. She went to high school in tenth grade. Then she went to summer camp for three months, and she picked up enough English to go to eleventh grade, and the next year she finished and got her high school diploma.

I went to bookkeeping classes. My husband had gone through the newspaper, and he said most job ads were for bookkeepers. I started working in San Jose at the British-American Club as a bookkeeper. My husband got a job in San Francisco in some architectural office. He went to San Francisco every single day in the morning, taking the bus, taking the train, and then working there, but of course it was very helpful because drawings are drawings so he could look at any drawing and understand what's going on.

After work, almost every day, he would take English classes. In Russia they used the metric system, but not here. So the owner of the company here said at his first interview, “You first have to learn about inches and feet.” Imagine, this was a man who was a big person in Russia, and so many people knew him because he was very knowledgeable about the old buildings in downtown St. Petersburg. He was accomplished there. He had worked many years already. He went to technical college, and after college he was in Russian army for three years because in Russia you must go into the army. So with his first job here he was like a beginner. He was treated like he was just starting out again. Because it was a different system, different buildings, different measurements, so it was a very difficult time for us. When we first came here, and I would say I'm from Russia, most Americans then knew only Siberia and vodka. I said, what about Tchaikovsky? What about the Bolshoi Ballet? Do you know anything besides Siberia and vodka?

We didn't have friends. We were very limited moneywise; he made just $3.75 per hour, and I made $2.50 per hour. We had a grownup daughter. We weren't hungry. We had enough food, but it was hard to go through such a transformation. Morally we were very down, but at the same time we were free! We felt like if we worked hard we could accomplish a lot. And that's how we started—day and night, sleep a few hours a day, but the main thing [was] our daughter did go to school and that was our main happiness, you know?

She graduated high school and then went to West Valley Community College. At the same time, she worked, and then she got married quite young. She was in her early twenties when she married a Jewish boy who also came from Russia, but after that she did go to San Jose State University, and he went there too and graduated, and that was our happiness and we could forget about all the difficult times. And, again, as I'm saying, it wasn't the same like people who went through Ellis Island, where nobody helped them—you know they just got there and that's it. But emotionally I would say it was an absolutely different atmosphere for us than Russia because we were free and we could do whatever we want. We knew if we worked hard we will get everything. But in Russia it didn't matter. You could work hard and get nothing, and if you were Jewish, you got less than nothing. You felt like a second-class citizen.

The first time when I went back to Russia with my husband was in ‘79. All my relatives came to talk to us, and we said, “You have to immigrate right away,” and actually the same year all my cousins from my mother's side, Isabel's aunt and all our cousins and children, they are all here now in San Jose, except for two cousins who are in Israel. We have no relatives anymore in Russia.

My husband went on to work for the city of Palo Alto for twenty-two years, and he did very well and was well known and respected in his field. I have a swimming pool. When my husband used to come home from work, the first thing he did was go for a swim. He loved to swim…. [She pauses.] Then three and a half years ago, I lost my husband. He had cancer. He never knew he had cancer, and he passed away in four days. [She pauses again, more upbeat.] But I have my two granddaughters. I have a beautiful house, and my daughter has a house, and my daughter paid for her children to go to private school and then to private university, and my daughter and her husband both work very hard, and I still work.

In America, if you work hard and you want something, you will get it. I am so happy we came here.

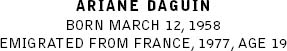

She comes from an affluent family of restaurateurs in the Gascony region of France. By the time she was nineteen, strainedfamily relations led her to America to make her mark. She considered journalism and studied political science but eventually returned to what she knew best: the food business. In 1985, with a partner, she started a company from scratch. It was a gourmet wholesale food company called D'Artagnan, named after the charismatic Gascony nobleman popularized by Alexandre Dumas in the novel The Three Musketeers. Today she has 123 employees and twenty-nine trucks, and she grossed more than $50 million in annual sales in 2009. She built a network of more than 250 farmers in ten states and abroad that supplies more than three thousand restaurants across the country, including virtually all the three-and four-star restaurants in New York, and is credited with being the first to make foie gras in America. She is the author of the book D'Artagnan in New York, which was recently published in France to rave reviews and recounts her travails in successfully building her business. “We started with $15,000,” she said. “The day we opened the door officially, we had thirty-five dollars left in the bank account.”

I come from Gascony in the southwest of France. I left to come to America for a bunch of reasons. I come from a family of restaurateurs. In my family everybody's in the food business. When they're not in the food business, they are in the farming business, or hunting or fishing. So ever since I was very little, all I learned about was food. In Gascony, everybody lives for food. So I wanted to see if there was something else in life. Also, my father owned a hotel/restaurant in Auch, the capital of Gascony, which got two Michelin stars. He's retired now, but he was a big figure in gastronomy and nouvelle cuisine. He invented how to cook the migrate, the breast of duck, and he was a big personality. I was the oldest child. My brother is a year younger and my little sister is seven years younger, and in the family it was never said, but it was clear that I was not going to take over the hotel area—that my brother was. He was groomed for it, but I wanted to show what I was worth. I was proud…so that's why I came here.

I like to write. So I thought maybe I would become a journalist. But I took political science at the university in Toulouse, and then one thing led to another, and I came to America and got a job as an au pair in Connecticut. I was accepted at Barnard College in political science, dropped out, and then worked as an employee at the Three Little Pigs, which was a charcuterie, a little store on Thirteenth Street in Manhattan. So I went right back into food. Why? I ran out of money. My parents and I were not really speaking at the time when I left to come here.

I would never have gone back to France because I didn't want to come back with nothing. I wanted to show that I could do something with my life. I really wanted to show that I could do something without my father's influence because I saw all the girls whose fathers were the same level as my father. They would end up in a public relations agency presenting champagne or something, and I would hear people say, “Oh, she's there because of her father,” and I really didn't want that. I wanted to show that I could do it on my own. I wanted to impress my parents—my father, in particular—and I was mad. I was the oldest, and I could have taken over the hotel.

But now I'm so glad that I didn't. I'm so glad that it turned out this way. I am totally thankful. Because I came here and I had to fight, and I ended up doing something that I love, starting a company that is my second baby and living a life that I really, really enjoy.

For five years, I worked at the Three Little Pigs. It's a retail store, but right away I said, “Instead of selling a slice of pate to the housewife, we should make the whole pate and sell it wholesale to Balducci's around the corner and all those specialty stores and gourmet shops,” and my bosses at the time, two French guys, said OK.

So I brought in a friend of mine I had met at Columbia University at the International House. His name was George [Faison]. He was in the dormitory there, and he was a Texan—everybody else was a foreigner; I guess they still think Texans are foreigners—and he was a young American who would come with us Europeans once a month. We would spend all of our money at a good restaurant, and he was the only American doing that with us. So we became friends, and he was finishing his MBA, and so he was ready for life and liked to live. And so I'm with those guys [at the Three Little Pigs] for a year now and we want to expand and do wholesale, and I said, “George, we need you,” and he joined us because the two owners were really overwhelmed. I was pretty good at selling, quality control, the new products; I was in charge of that, all the logistics and the finance. But the owners didn't have much of an education in France. They knew how to cook and they made pates, but soon it became bigger than them, you know?

I stuck with them for five years, and one day two guys arrived with foie gras in their hands. This was 1979, and I couldn't believe it: “What do you mean, foie gras?” I thought it was not allowed in America. They said, “What do you mean? There is no law against this.” They were Israeli and they came with American partners, and they had started a farm here for making foie gras up in Monticello, New York, and they wanted to see how they could sell the stuff commercially. Their forte was the processing and the slaughterhouse and the breeding and all that stuff, so I absolutely wanted to be a part of this. For me, it was historical. The first foie gras in America!

I started the negotiations. Then one day, my bosses and I went up to the farm in Monticello, and on the way up they talked with each other about it really for the first time. They knew where I stood on this. And along the way, during the two-and-a-half-hour drive, they became more and more against signing the exclusivity agreement.

I was so pissed off and sad, beyond belief! I had worked on this for three months to convince those farmers that we would be the only ones carrying their product, and what we would do with the rest of the duck—the breast, the legs, etc.—because the foie gras, the liver, was the most valuable, but you can't throw away the rest; this is where the money is, where you make it or not, you know?

But the father there who owned the farm threw us out, and that was that. They found an excuse not to sign. They insinuated that there was something fishy, and the father got really upset and said, “You're in my office—get out!” [She laughs.] And my two bosses were saying, “You know, it's a good thing we didn't go into this,” because they had built a good business. They didn't need to take any risks. They had six pates; life was good. When one was on vacation and came back the other one went, and so everything was cool. So they didn't want to risk it.

It was on the way back in the van when I knew I was going to start my own company. And I talked with my friend George, and after more than a couple of lunches with margaritas, I convinced him and he said, “OK, let's do it!”

Meanwhile, by the time I convinced him, we had already started looking for a place and put together a business plan where it wouldn't be only foie gras, because we couldn't survive. We needed game and poultry and good food for restaurants. By the time we did that, the farmers in Monticello had panicked already and started selling to butchers and meat wholesalers in Manhattan. So we had to convince them that they needed one more, which they really didn't, but they went for it. We had to pay COD. George resigned from the Three Little Pigs. I stayed. On Sundays I would take the van, go to the farm in Monticello, check the foie gras, and choose them. During the week we would sell them, organize everything, and then after three weeks, I also resigned and we started D'Artagnan!

We started at the beginning of ‘85, and it went truly well for several years. It was very hard every day. And every day for the first three years, either George or I would come and say, “OK, I'm not coming tomorrow. I leave you the company; it's too hard, too much,” and every day, one of us would say, “One more day, just one more day.” The company was located in Newark, New Jersey, because it's close to the airport, near Manhattan, good highways in the northeast corridor from Boston to Washington, DC, for shipping. We started with $15,000. The day we opened the door officially, we had thirty-five dollars left in the bank account. Because we had to pay three months' rent, we had to find a truck. The truck was a lease we took over from a guy who wanted to do some orange juice thing that didn't work out—it had to be a refrigerated truck—but we needed a logo to paint on the truck.

We discovered the logo at a bistro in Greenwich Village and the bartender overheard us. We were deciding the name of the company, and I said, “D'Artagnan, it has to be D'Artagnan,” and then the bartender overheard and said, “You know, in my native country in Russia, I'm a graphic designer.” So we explained the company and it's going to be called D'Artagnan, named after the musketeer, and in two seconds on a cocktail napkin he drew the logo that we still have today! We took our last $2,000 to paint the logo on the truck. At the time I was living in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, which was not as civilized as today, and I parked the truck. The next morning, there was graffiti all over it. I cried on the sidewalk….

George and I eventually had a big breakdown. He tried to buy me out…. We had a clause between us. It's called a “shotgun clause.” We were partners fifty-fifty, so we had to take out life insurance—one partner on the other partner—that if something happens to one partner and they die, the other partner has life insurance for half the value of the company. In that way, the company doesn't suffer the loss of one of the partners.

The shotgun clause also said that if one day one partner doesn't agree with the other, they have the right to put an offer on the table—any offer—and the other one cannot say no. The value is set by the first partner, and the second cannot go lower or higher—the value is already set. It's either, “Yeah, I take it” [sell you my half at that price], or “No, it's me” [buy your half at that price]. So George did that to me, [but] as part of the terms he said, “Thirty days.” In other words, the terms in his letter were the amount of money and thirty days. But the amount was so enormous, there was no way I could raise it in thirty days. It was impossible.

In the meantime, my daughter and I were supposed to leave on vacation for three weeks to China, and everything was organized with friends of mine. So that weekend I called my daughter, who was at my parents' in Gascony, and I said, “I don't think I'm going to be able to come to China because I have this thing that's happening with George, and I'm sorry.” She was fifteen at the time. “Do you still want to go to China?” We were to go with a friend of mine and his boy. They all knew each other, and she said, “Yeah, I want to go to China,” and then she realized that I was not going to come, and then she realized what I just said—that I may lose the company—and she said, “But what if I wanted to work at D'Artagnan one day?”

And that's when it hit home. That was the thing that made me want to keep it at any price. Over the years she went to demos with me. We did cooking classes together. We were attached at the hip, you know? And I'm not married, but that touched my heart. Because up until then, I was thinking, “What do I do? It's a lot of money maybe I should just forget it and go back to France, open a little restaurant, and that's it.”

But after what she said, I was resolved: “I have to get it! He's not going to do this to me after twenty years of business together. I cannot let that happen. I have to find that money!” I cannot say how much, but it was several million dollars for me to buy him out.

So I knocked on doors and realized in July everybody was on vacation and it was going to be very difficult. And I was at the Fancy Food Show in Manhattan, and I had three bankers who came to visit me at the booth, which was very difficult because George was there. We were both looking at each other. The employees knew something was dead wrong; it was so bad. And one banker, a French banker, said, “I'm going to help you,” and he did. He went to France. He called me. I remember it was Bastille Day, and he said, “Yesterday I had a meeting with my guys, and it's a goahead!” That was July 14. George had given me the shotgun clause on June 17, so I had to declare my intention on July 17—so I made it by three days, just in time. I remember I was in front of Provence, the French bistro [since closed] in the meatpacking district, and I bought a drink for everybody and nobody knew why. [She laughs.]

My father and I made up. When the company started to stand on its own and I started to have good publicity, he became very proud of me, but he never said anything to me. Never! He doesn't talk. Even this year, our twenty-fifth anniversary, we did a big party. I invited two thousand people to Guastavino's, under the Queensboro Bridge. We had a big plane full of Gascony people who came to the party—chefs, rugby players, musicians, friends, family, my parents. We asked everybody to dress in red and white, which are the colors of D'Artagnan but also the colors of Auch, my hometown. And the next day people said, “Wow! Your father was so proud!” And I didn't know. He never told me. Even then, he never said a word.

I got my green card in 1986, and I literally just got my citizenship certificate the other day [June 2010]. I passed the test last month and took the official oath of allegiance. I could have done it a long time ago because I love America, but it was time. Now every time I go to France and come back, Customs cannot look at me like, “If you're not a citizen, why are you here?” Which I can understand.

I love France, of course. And when I went on the book tour in May [2010] in Paris, every journalist at some point asked me one question: “And where are you going to end your days?” But they said it in a way that [meant] I better stay in France because that's what they were expecting to hear. And frankly, every time, I said, “I don't know,” which was the truth. I have deep, deep roots with my region of France. I'm not French; I'm Gascon. That's why I named my company after D'Artagnan. He was a hero who really lived in Gascony, was very loyal to his friends, to his family, and, of course, to the king and, especially, the queen. He was a guy who wanted to do things with panache, and that's what I wanted in my company. I wanted to do things with panache. And to this day, I think we've been pretty successful at doing that. Doing it the right way for the beauty of it, not for the “What's in it for me?” It's a totally Gascon way of seeing things, I think. We all think in Gascony that we're descendants of D'Artagnan—the panache, the loyalty, the grand gesture. [She pauses.] But I live here. I love it here. So I decided to become a citizen. I decided this is my country now.

His is an amazing story of faith and recovery. He grew up in the outback of western Ontario, Canada, until age twelve. He emigrated to America when his father accepted a position as pastor at a Baptist church in rural Kentucky. Like his father, he, too, became a pastor. He was twenty-eight, in the prime of his life—newly married, in a new home, having just accepted a new job as pastor of a church, his wife pregnant with their first child—when a fluke car accident revealed he had cancer and had less than a year to live. Against all odds, enduring a remarkable test of faith, he somehow survived the ordeal and eventually returned with his family to his native Canada, a living, walking miracle of a man.

My father was a pastor, so I guess it makes sense that I would become a pastor too. My family is Scots-Irish. Over the centuries, my family historically migrated from Scotland to the west of Ireland, then to Nova Scotia in the Canadian Maritimes, and finally to Ontario, Canada. I grew up in a small rural town in western Ontario. I lived there for the first twelve years of my life. Then my father was offered a job as a pastor at a Baptist church in Kentucky, and we moved there. It was my parents and me. I was an only child.

We moved from Canada to Ashland, Kentucky; it's a small town on the Ohio River near the state lines of Ohio, Kentucky, and West Virginia. It was your typical Midwest river town, where life was slow, family-oriented, with school during the week, church on Sundays, solid American, but very sheltered. There wasn't a lot of crime or violence. It was a nice place to live and raise kids. My father was a pastor at a local Baptist church. My mother was a homemaker.

From an early age, I went to church. I became a believer at age five, was baptized at age six, and by age seventeen, I felt the call from God to go into the ministry. God had been tugging at my heart for some time. I was a youth pastor well into my early twenties. I went to a local college, Marshall University, and graduated with a teaching degree, and then spent one year attending Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, and that changed me. For the first time I saw life through the lens of a large city and not just a small town.

When I went to Chicago, I saw things I'd never seen before. I was a twenty-one-year-old kid, and on Sunday morning I would go with a ministry team to a rest home. I was the preacher. I had a song leader and a couple of others who came along, and every week we had to go to the South Side of Chicago, which was not exactly the best part of town. I saw how great the diversities are and the needs are in urban areas; just the whole cultural dynamic gripped me, and I felt like God was preparing me to have a larger vision than just what I had seen up to that point. I learned two things: awareness—that God wanted me to see things through his eyes, not just through my eyes—and the second thing I learned was preparation, that I needed to really prepare well if I was going to become a successful pastor.

After graduating from Marshall University, I studied for three years at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, in my quest for preparation. I totally engulfed myself, learning Greek, Hebrew, and then I had all the biblical training.

After that, I was called to pastor at a rural church deep in the heart of Appalachia. They were without a pastor, and I was single at the time, twenty-seven years old. The church had gone through some transition, and so I came in as a young minister trying to revive it.

I met my wife, Sara, there. Of course, you have to remember, as a single pastor a lot of people wanted to fix me up with their daughters or granddaughters. There was a guy in our church who said, “One of these days, someone is going to walk through that back door and you're going to know it's the right person.” Sure enough, I was preaching one Sunday and Sara walked in. I had seen her a hundred times, and maybe it was the glow of the light coming through the window that day, but I thought, “That's the person for me.”

One year later, I proposed to Sara. Three months later, we were married and awaiting word on an open position for pastor of a Baptist church in northern Kentucky, near Cincinnati. By this time, I had developed a reputation as an excellent pulpit pastor who gave concise, well-organized sermons without looking at his notes. I got the job, and we moved to northern Kentucky and our new home.

It was the fall of 1995, and I was feeling on top of the world. I was a young pastor, newly married to a beautiful brunette. We honeymooned in Florida, and then I started work as pastor of the church. That year just seemed like a lot of firsts for us. Sara and I had our first Thanksgiving together. We had our first Christmas together. As newlyweds, we had also just spent our first Easter together, and by this time Sara was six months pregnant with our first child. Then one ordinary morning in May, everything changed.

I was about to begin my daily routine, which included a visit to a local hospital in Covington, Kentucky, a short distance from downtown Cincinnati, making my rounds offering prayer and solace to those in need. But en route to the hospital, I stopped at a traffic light. Just then, a gasoline tanker traveling approximately forty-five miles per hour failed to brake and slammed into the rear of my car. The impact sent it clear across a main intersection. Fortunately for me, there were no oncoming cars. I had my seatbelt on, and my airbag was deployed, but I didn't feel any pain. It didn't seem like anything was wrong, really, but EMS suggested I go to the hospital for an x-ray.

The doctors didn't like what they saw, so they took additional x-rays, a CT scan, and made an appointment for me to be examined by an oncologist. I suffered no ill effects from the accident. The problem lay elsewhere, it seemed. The doctors told me, “There's a very large mass in your chest,” something the size of a softball, that the mass was around my lungs and heart—the whole chest area. It was a large tumor, too large to operate. They did a biopsy from the neck, which revealed it was stage two non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer. The doctors told me the accident may have saved my life because they said, “If we hadn't found this, you'd probably be gone within a year.”

They also said that because of the location and type of cancer that it was, surgery was not an option. I was going to need six to eight months of intensive chemotherapy and radiation treatments, ending sometime around Christmas. The treatments were heavy chemotherapy doses once every three weeks, with radiation treatments one day per week for two months. The doctors said the best-case scenario was that they would somehow shrink the tumor and give me a few more years.

My wife and I were in disbelief. How could this be? Sara really took it hard. This was shocking to her. She was living with me in our new life together. She was pregnant, and now she was faced with the prospect that I may not live and our child may grow up without a father.

I couldn't believe it was happening. I remember being alone in the master bedroom of our home. I just wanted to be by myself. I remember thinking, “This is not the way it's supposed to be,” and I cried out to God. I asked him, “Is this really happening?” And then I felt this sense of assurance that swept over my body, saying to me, “This will be OK.”

The Old Testament speaks about the “still small voice.” I felt like God spoke to me through his Holy Spirit, that “this is all in my greater good.” He didn't tell me I was going to be healed. He just said, “I am with you.” His presence felt so real. I felt him saying to me, “I'm going to get you through this whole process.”

So I was probably in denial no more than twenty minutes. I felt drawn to the Bible and particularly Philippians 4:4–7, which I read every day: “Rejoice in the Lord always; again I will say, Rejoice. Let all men know your forbearance. The Lord is at hand. Have no anxiety about anything, but in everything by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving let your requests be made known to God. And the peace of God which transcends all understanding will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus.”

In the following weeks, the disease and the treatment took a real toll on me physically. I lost all my hair. I was pale, gaunt, emaciated looking. I lost much of my energy and strength, and there was a terrible metallic taste in my mouth that never seemed to go away so that food never tasted good. I started to wear hats to protect my bald scalp against sunburn. I was never sick growing up. Just the opposite. I was healthy. Athletic. I didn't smoke or drink. In addition, the irony for me: here I had gone to visit hundreds of people in the hospital over the years—cancer patients, all kinds of patients with serious illness—but I never thought that I would be one of them.

The doctors didn't understand. They said it could be from environmental factors. Genetic factors. I once had an uncle who died of stomach cancer.

There were many questions that I had, but I always found myself going back to the Bible, to scripture, to resolve them. First of all, you have to understand that both believers and nonbelievers can say that it's not God punishing me per se, and that it could be for the greater good of humanity, so to speak; that oftentimes God has cured people, oftentimes he allows us to go through tests and trials to demonstrate his compassion and love, and I really came to the conclusion that if this was God's course for my life, so be it. If I were to pass, and then there was a greater good, then both Sara and I were comfortable in knowing that we had done everything we could and that it was out of our hands because we sought out the best doctors and followed the medical regimen to the T.

In addition, as part of my daily regimen I took walks and read verse. Pray and walk, that's what I did for six months. I felt very reassured that God was going to take care of me, so I really put my faith in him. There were many scripture passages that were therapeutic for me.

But it was Sara who held me together. She did this through her love and refused to let me feel sorry for myself. She has such strength of character. She said things like, “We're going to beat this! We're going to get better!” We developed a strong “we can get through anything” bond. Doctors would fill my body up with chemicals, and I knew I would throw up, but this one particular time, I just couldn't make it to the bathroom of our new house, and I threw up in the kitchen, on the carpet, in the sink, everywhere, and there she was, cleaning up my vomit. It was a very humbling experience.

Then there was the emotional stress of not knowing if my sickness would negatively affect our child in Sara's womb. A sonogram told us it was a boy. Would I be alive to see my son's birth, or even the first few months of his life? But that wasn't all. The doctors told us that due to the chemotherapy, we'd probably never be able to have more children.

In the meantime, I continued to preach every Sunday, as much for my sanity as to reassure the congregation that they were not going to lose their pastor. After all, it had taken the church more than two years to find a new one. I could see the uncertainty every Sunday morning when I preached. I had only been there about seven months. The congregation looked sympathetically toward me: “Here's someone going through pain; let's see if his message matches his faith,” but there were doubts and concern. I mean, several people told me, “Until we get the all-clear sign, we still don't think you're going to make it.” And they just didn't want to get too close, too emotionally attached. They had just lost a previous pastor, and they were just getting to know us, and then I got sick, and so the attitude of many church members was, “We're going to back off until we know that you're going to be around.”

Sometimes I wasn't even aware of how the congregation was behind me because when you go through something like this, you have to walk it alone. I know there were times I absolutely dragged myself to the church for services so as to not to let the church congregation down. I kept them apprised of my medical situation and infused my sermons with the circumstances of my life. One of the phrases I used a lot during this time was, “You can't get bitter—you gotta get better.” Meaning you can't get bitter toward God. He has a plan, and it's going to see its course.

We received hundreds of cards and phone calls, and we were on prayer chains across the state of Kentucky. Of course, my mother was at our home almost daily, especially after one of my four-hour treatments, and my condition was showing no improvement. I was about to have my sixth and final chemotherapy session when the doctors informed me that a CT scan revealed that the mass in my chest had not shrunk and requested that I undergo additional treatments, and that shocked me.

I didn't expect that. Neither did Sara. She was now in her third trimester, and things looked really bleak. I felt really bleak. And I didn't understand all that was happening. I had faith. I had people praying for me. I had been anointed in the name of God to be healed—so I had all of it.

It felt like our faith was being tested. One day, a woman, a complete stranger, came into my office and said, “I just want to tell you that I heard about your plight and I have bad news: You're not going to make it! God has something else in store for you,” and she left like some demonic apparition.

“Who was that?” my secretary asked.

“I don't know,” I said. And I never saw her again.

Another time, Sara answered the phone and allowed a salesman to make an appointment, not really knowing what the appointment was for. Turns out it was someone selling plots at the local graveyard. My mother answered the door and she was stunned. She said, “Why are we having this conversation?” She thought Sara and I had made arrangements to buy cemetery plots.

We were feeling low and weary from the stress. We decided to get away for Labor Day weekend to Lake Cumberland in Tennessee. A church member had offered us use of his cabin. So we decided to go there and look at life and hold each other a little tighter. One afternoon, we went to the swimming pool and started talking about what if I don't make it. We talked about the financial aspects of it. Would Sara go back to live with her parents? Or would she stay in Kentucky with an infant? We had to have this conversation. It wasn't something we wanted to have, certainly not in the first year as husband and wife. But there we were having this conversation of what-ifs. I remember some insurance company once itemized the big stresses in life: a move is a big stressor, a new house is a big stressor, an illness, and the birth of a child. I mean, we had all of them going at the same time.

Then, at some point during that weekend, our attitudes became more optimistic, and we said, “Let's go forward and talk about the birth of our son.” We were thinking negatively—that maybe things won't go well, maybe I had only a year to live, but our son was still going to be born, so we started channeling our energies positively as to what we could do to make his arrival great, which was only a few weeks away.

Driving back home from Lake Cumberland, I recall feeling what a blessing that weekend had been because it just rekindled our honeymoon all over again. I felt so happy that I had married her. I didn't want that weekend to end—physically, spiritually. Of course, we believed that God was going to take care of us. We were just leaning on him.

The key scripture for me was [Philippians 4:7]: “And the peace of God, which transcends all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus.”

I felt like not only was God guarding my heart with that scripture, he was guarding my mind, too, because it was almost like he gave me a covering of protection so that I wouldn't think too far ahead, and in that way stay positive.

But once home, reality set in. It was an emotional low point when the ladies of the church held a baby shower for Sara. We came in that night, and the ladies knew things weren't going well medically, and I think they felt more sorry for us than happy for us, and that they were going to have to find a new pastor again, and that Sara would likely be moving back home, and I'll be in heaven. Gone. This was the bottom.

Then one day, I went to the hospital for a special SPECT scan: a threehour procedure in which doctors had me drink dye to get a good look at the inside of my body. Everything in a SPECT scan is either green or red. The green is healthy tissue; red is the tumor. The doctor said he would get back to me in a couple of days, but the technician already had the results and let me see them.

I looked at the chart and it looked all green! I was thinking, “Praise God. Thank you, God.” I had completed all of my chemotherapy treatments, and it was just miraculous! After the doctor told me the results in person, it was an even greater relief. He couldn't believe it. He was elated! I don't think I heard him say “miracle,” but I know he was thinking that. I think it certainly was an act of God, working through those doctors, through those medicines, that he divinely allowed me to heal—not just physically, but emotionally, mentally, spiritually.

I immediately called home. Sara and I both cried. My father wasn't an emotional person, so he didn't like to talk about my illness. It was something we didn't bring up much, but when I was healed, it was like the weight was off his shoulders. He cried. My mother cried….

I reported back to the congregation the joyful news. It was a Sunday service, the first Sunday after Thanksgiving. The congregation of 350 stood on its feet and applauded. Sara beamed. I tried to sum up my feelings that day, which is that God had really guided my heart and my mind. That God can take the bad and turn it into good, that he's in control! I was feeling not only hopeful, but that God was going to bring hope and happiness to a lot of people in the congregation who had been there with us and sacrificed and prayed and connected with us through our pain. One man said after the service, “You're the only miracle I know.”

Soon after, we were blessed with a healthy seven-pound, four-ounce, brown-haired baby boy!

I remember that day. I just drove around for an hour by myself, listening to my favorite spiritual songs on the car CD player. It was just a beautiful, bright sunny day, and I thought, “I've got my health, I've got my son, I'm going to live! I'm going to enjoy life! I'm so blessed!”

The following year, we were quite surprised when we had our second child, a daughter, and even more surprised two years after that when we had our third child, a son. We were so thrilled to have three healthy children! As far as my health, the doctors say I am cured, the cancer in total remission.

Now I wake up every day thanking God for the blessing and the challenges—because God has allowed us to go through this for a reason, and it's to help others. It's to be an encouragement. I think my surviving cancer was another event to help me become a better pastor. I see it all as a connection. To be a better minister and a better person, and to be able to really minister to people where they are. That's what I want to do. I've learned that even in the darkest valley, God will be with you if you allow him to be.

A few years later, my parents returned to Canada, and Sara and I decided to go as well and keep the family together. Her parents had already passed. And we'd done our work here. It was time to go home. The children were still young. They, of course, were born here, so they're American citizens. So, of course, was Sara. But interestingly enough, my father, mother, and me—none of us ever became citizens. We had our green cards, but that's all.

So we returned to Canada and the life we once knew. It was a simpler life, and that's what we wanted. Fewer people. Less congestion. Less complication. Less drama. More open land. Lakes and streams. Beautiful scenery. Nature. The hand of God everywhere; after all we went through, both for ourselves and our children, this is what we wanted to be near: the hand of God.

That's my story.

1972:

1972: