IMMIGRATION IN THE GOLDEN ERA

For more centuries than one can count, humans have traversed the world in search of a better life, one in which freedom, food, riches, jobs, or simply the thrill of adventure has loomed large. In the late fifteenth century, Columbus's discovery of the “New World” and the subsequent spread of colonialism throughout it made that hemisphere a natural magnet for more immigrants. Since 1800, the United States has attracted more immigrants than any other nation on earth. The country's political and economic liberalism, its vastness, the extraordinary wealth and resources of land, and the general prosperity of its inhabitants have drawn countless “greenhorns” to its shores.

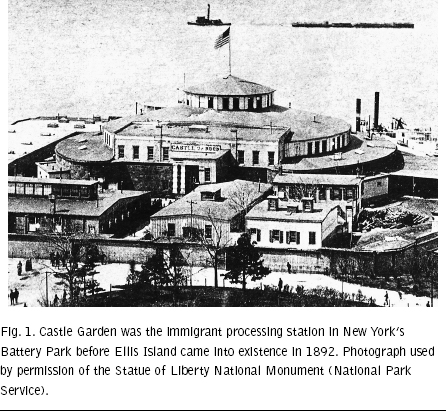

Beginning in the 1830s, the waves of immigrants boosted the country's growth: they gave it the strength to achieve its aims, not the least of which was the opening of the West to white settlement. Not long after the Civil War, there was a marked decline in immigration due to a number of factors, including the effects of a severe economic slump in 1873. But the next decade, the 1880s, saw a massive upsurge of newcomers, mostly pouring in through New York's Castle Garden Emigrant Landing Depot. One reason for this development was that a great many people were coming from an unexpected quarter: the far distant kingdoms of eastern and southern Europe, lands that had previously sent few immigrants. Known as the “New Immigrants,” these sorts of Europeans differed markedly from the “Old Immigrants,” who hailed from such countries as Germany, Ireland, Great Britain, Scandinavia, Austria, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and northern Italy. To English America, the earlier group was welcome in spite of their differences, while the New Immigrants, from lands far, far away, seemed much too foreign to be successfully assimilated into American society.

Even worse, Protestant critics bewailed the fact that the New Immigrants were almost all Roman Catholic, Jewish, or Eastern Orthodox Christians, faiths that easily aroused Protestant suspicion and, at times, even open hostility. For this and other reasons, a good many Americans began to doubt the value of mass immigration, and some even proposed that it was time to close the “golden door” altogether.

In 1882, the federal government began enacting laws to bar undesirable immigrants, but in order to win the compliance of the states, the imposed Immigration Act charged each arriving alien a “head tax” of fifty cents, and the funds were then reimbursed to those states that actively enforced federal regulations. New York naturally received the bulk of this relief money, helping it to continue operating Castle Garden Emigrant Landing Depot as well as the state immigrant hospital and refugee buildings on Wards Island. The same legislation barred the entry of “convicts, lunatics, idiots, and persons likely to become a public charge.” A separate law adopted in the same year was the racist Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred the entry of certain laborers based on their ethnicity. In 1885, another law was passed, this time barring all foreign workers brought in under contract. The federal government passed this law to silence the boisterous complaints by the union leaders in the Knights of Labor, who had alleged that a vast number of American workers were losing jobs through the deliberate importation of foreign laborers. This law was aimed partly at Italians, thousands of whom were being brought into the country on a regular basis by men called padrones. These small-time businessmen earned lucrative commissions from manufacturers and other American firms needing reliable workers whom they could pay the lowest of wages without much complaint. In addition, padrones' immigrant wards paid them a commission out of their meager earnings.

The padrones had long been importing southern Italians and Greeks to work in their own small-scale enterprises, such as blacking boots, playing music in the streets and cafes, peddling fruits and vegetables, and making candy. Other nationalities brought in by padrones of their own included Croatians, Mexicans, and Japanese.

Not surprisingly, the state that had the greatest difficulty in satisfying the federal government in this matter of turning away undesirables was also the nation's leading port. Each year, the port of New York received as much as 75 percent of all immigration. In consequence, when the question of immigrants arose, the eyes of the nation naturally turned to New York State's Board of Emigration Commissioners and its Castle Garden Emigrant Landing Depot at the tip of lower Manhattan.

The US government considered the New York immigrant landing system seriously flawed. What dissatisfied lawmakers most was the lack of any real scrutiny: What went on at Castle Garden amounted to no more than a mere recording and tabulation of personal details about each immigrant in large ledgers—there was practically no screening. In addition, unsavory conditions such as dirt, dishonesty, and corruption were commonplace. Some people also complained about the work of Mormon missionaries, who were assisting thousands of northern and western Europeans to emigrate. Because of the church's traditional advocacy of polygamy, many felt it should not be permitted this role.

Debates about these and related questions compelled the federal government to assume full control of immigrant reception in 1890, and the United States Department of the Treasury was put in charge. In terms of bureaucracy, this was a sensible decision, since the Treasury Department was already running the Customs Service and the Marine Hospital Service, both of which carried out their duties at domestic seaports. With the consent of President Benjamin Harrison and Congress, the Secretary of the Treasury approved plans to construct the nation's first federal inspection station over on Ellis Island in New York Harbor. Meanwhile, immigrant reception was temporarily transferred from Castle Garden to a nearby federal building called the Barge Office. In 1891, Congress created a new Treasury Department agency to regulate immigration: the United States Bureau of Immigration. At the time, a new set of immigration policies introduced entirely new procedures such as “immigrant inspection,” as well as instructions for what steamship pursers should write on the ships' passenger lists and precise regulations governing the exclusion and the deportation of undesirable or inadmissible aliens.

The same decade saw an even heavier immigration of the newer ethnic groups: southern Italians, Orthodox Jews, Poles, Slovaks, Lithuanians, Finns, and Bulgarians, as well as Greeks, Portuguese, Spaniards, Armenians, Syrian Arabs, Turks, Hindus and Sikhs, West Indian blacks, and Gypsies. All arrived, ship after ship, much to the consternation of a growing circle of Americans demanding far stricter immigration laws.

From 1892 to 1910, a nationwide immigration control system was brought into operation: a chain of immigrant inspection stations was set up at all ports and border crossings. In addition to New York's Ellis Island, federal immigrant stations were opened at Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Detroit, Chicago, Seattle, Portland, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Honolulu, El Paso, Galveston, New Orleans, Mobile, Jacksonville, Savannah, Norfolk, San Juan, and the foreign cities of Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver, which required the consent of the Dominion of Canada.

At the turn of the century, immigration began to rise, and it continued to surge at an astounding rate. Ellis Island was tremendously overcrowded: as many as fifty thousand aliens had to be examined at the little island in the bay each week. In response to this situation, the government hastily began enlarging the isle through land filling; this was followed by the construction of desperately needed medical and other support buildings. Additionally, newer and stricter regulations came into force. Inspectors were more than ever on the lookout for undesirable aliens, such as foreign prostitutes and their procurers (“the white slave traffic”), unwed mothers, those certified as having “poor physiques,” those considered “feebleminded,” and those suffering from the dreaded eye ailment known as trachoma. In 1903, suspect political beliefs were added to the list when anarchists were barred under the Immigration Act of that year. This law also raised the head tax to two dollars and barred the entry of epileptics and beggars.

Meanwhile, the flow of eastern European Jews increased dramatically due to the outbreak of hundreds and hundreds of vicious pogroms against them (1903–1906). The Bureau of Immigration sent a number of immigrant inspectors to investigate the causes of the massive exodus. Yet it was also apparent that in spite of the ugly outrage of the pogroms, the vast majority of Jewish emigration was mostly impelled by a burning desire to escape the age-old poverty that had been their lot for generations. For them, coming to America was a dream come true.

Balkan and Levantine (the Levant region includes Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Iraq) immigration also rose in this decade. Greeks, Romanians, Serbs, Croats, Bulgarians, Albanians, Bosnians, and others made the long trek to America. The stream of ships on which they sailed usually came from Marseilles, Naples, Patras, Piraeus, Constantinople, and Alexandria; the same vessels were also crowded with hopefuls from Syria, Armenia, Turkey, and Malta, while more emigrants were setting out from Spanish and Portuguese ports. Although the basic reasons for migrating were pretty much the same for all these people—namely, to escape dire poverty and help their families better themselves—there were other causes, such as avoiding discrimination, bigotry, prejudice, war, violence, forced military service, Old World customs and traditions, or forced marriages.

As one might expect, the steamship lines made quite a bundle from the lucrative business of transporting emigrants. After the United States, they found that Canada, Argentina, Brazil, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa were popular destinations for migrants.

In 1907, the federal government, reacting to rising opposition to Japanese immigrants, entered into a diplomatic understanding with the Empire of Japan to curtail immigration from that country. Called the “Gentlemen's Agreement,” it consisted of promises by the United States government not to pass a Japanese exclusion law and by the Imperial Japanese government to halt further Japanese immigration to the United States.

In 1910, refugees from south of the border began fleeing into Texas, Arizona, and California to escape turmoil and save their lives. Called the Mexican Revolution, this civil war went on for ten years, during which the United States received 890,000 Mexican refugees. This eventually led to the 1924 founding of a new federal agency: the United States Border Patrol. That agency's task was to block illegal entry along the Mexican and Canadian borders.

During this same period, the immigration restriction movement gained momentum. World War I contributed to this in a big way by creating a lull in mass emigration, indicating that America's mills, mines, manufacturers, builders, farming estates, and other large concerns could manage sufficiently well without the massive numbers of newcomers to bolster the workforce. The restrictionists marched to victory on the political front, inspired on one hand by the swift growth of the fiercely antiimmigrant, anti-Catholic Ku Klux Klan, and, on the other hand, by the nationwide Americanization movement; the movement, represented by respected organizations like the YMCA and the Protestant Episcopal Church, took place primarily between 1895 and 1924 and aimed to help immigrants assimilate into American culture. In 1917, Congress enacted the Literacy Act, which barred the immigration of illiterate people. Its sponsors knew quite well that the new law would block the entry of groups known to have low rates of literacy, such as Orthodox Jewish women and Christian peasants from southern Italy, Portugal, and eastern Europe. Although this was an important law, it did not satisfy the restrictionists, who had far higher ambitions: They wanted Congress to pass legislation to end European mass migration for good. Their goal was finally achieved with the passage of the immigration quota acts of 1921 and 1924. Of the two, the 1924 law was the more severe, as it cut immigration to a trickle by the end of the decade.

However, before the May 1924 law was adopted, the United States had already received an overflow of fresh immigrants and refugees following quickly on the heels of postwar peace. From 1919 to 1924, thousands poured into Ellis Island and other stations: Germans, Austrians, Russians, Hungarians, Romanians, Irish, Armenians, Greeks, Jews, Italians, and people of just about every other Old World nationality were trying to get in before any new restriction laws could come into force.

As mass migration came to an end, the Bureau of Immigration changed many of its operations. With far fewer “immigrant inspections” needed at Ellis Island and elsewhere, bureau officials decided to step up domestic enforcement on illegal aliens residing in the United States. Designating Ellis Island as the national headquarters for deportation and other warrant cases, they perfected a system of investigating, arresting, and transporting great numbers of aliens who had transgressed the laws of the land. These “deportation parties” involved the use of trains traveling across the country and halting in rural areas and urban communities to pick up deportees from the local law enforcement officials. The trains operated every four to six weeks, beginning their eastward journeys from two points: San Francisco and Seattle. The duty staff consisted of men called “immigrant inspectors,” as well as armed guards, matrons, and physicians. The end of the line was Jersey City, New Jersey, from which the detainees were transferred to Ellis Island by steamboats. These deportation trains remained a significant part of US policy from 1920 through the 1940s.

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, immigration virtually ended; even the limited quotas often went unfilled. In fact, for the first time in American history, statistics showed more people leaving the United States than entering it. Of course, the gradual improvement in the economy began reversing this trend, especially as war clouds gathered over Asia, Europe, and east Africa just before the outbreak of World War II.

While nationalism and war fever convinced many loyal German and Italian immigrants to return to their beloved homelands in support of fascism, thousands of people over in Europe, abhorring the change of events there, began fleeing to the United States, Canada, England, Palestine, Latin America, and elsewhere. Hitler's victorious conquests of Poland, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, France, Yugoslavia, and Greece meant the hundreds of thousands of refugees from those places would now have to be labeled as “stateless” aliens. Ellis Island became a way station for those seeking refuge in the United States.

The war also exacted a severe toll on German, Italian, and Japanese nationals living in the United States. In December 1941, President Roosevelt signed an executive order proclaiming them “alien enemies.” This affected more than nine hundred thousand people. Thousands of them found themselves under FBI surveillance, and at least ten thousand were actually arrested and taken to immigrant stations such as Ellis Island for investigation. In fact, even respectable American citizens were not exempt; in a decision clearly motivated by racism and xenophobia, President Roosevelt stripped US citizens of Japanese descent of their civil rights by signing an executive order that forced them out of their homes and into internment camps throughout the western states.

With the end of the war, Congress passed the War Brides Act of 1945, which permitted spouses and adopted children of American military personnel to enter the United States without waiting for a quota number. Meanwhile, President Roosevelt had already set up a War Refugee Board and subsequent legislation for helping European refugees and displaced persons enter the United States more easily.

By 1950, the Cold War was in full swing and Communism had become distinctly unpopular. The Internal Security Act blocked the immigration of subversives, such as communists and fascists. Ellis Island once more came into play as a leading detention facility for arriving foreigners suspected or known to be involved in subversive activities. Perhaps the most notable of these cases were those of Ignatz Mezei, “the man without a country,” who was held for forty-three months, and Ellen Knauff, a war bride who was held for twenty-two months; after long struggles, both eventually won their appeals and were released. By 1954, Ellis Island was determined to be too large and too expensive to operate, and it was closed permanently on November 12, 1954, ending the first great era of US federal immigration control.

It also marked the beginning of the next great era and America's “new immigrants.” In Toward a Better Life, you will hear the first-person stories of immigrants from both eras and experience what they endured as you take the journey across one hundred twenty years of immigration to America.

Barry Moreno

Historian, Ellis Island Immigration Museum, and

Author of The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Ellis Island