THE QUEST FOR EQUAL RIGHTS IN THE NORTH

THE QUEST FOR EQUAL RIGHTS IN THE NORTHX  THE QUEST FOR EQUAL RIGHTS IN THE NORTH

THE QUEST FOR EQUAL RIGHTS IN THE NORTH

BY 1863 the Civil War had become a revolution of freedom for 4 million slaves. The antislavery crusade, however, envisaged not only a negative freedom—the absence of chattelism—but a positive guaranty of equal protection of the laws to all men. Once freedom was won, most abolitionists were ready to proceed with the next step in the revolution—equality.

“This is a war not of geographical sections, nor of political factions, but of principles and systems,” declared Theodore Tilton in 1863. “Our war against this rebellion is … a war for social equality, for rights, for justice, for freedom.” In 1863 Moncure Conway wrote that “the war raging in America must be referred to a higher plane than that of Liberty. It is a war for Equality. It is to decide whether the Liberty which each race claims for itself, and knows to be good, shall be given impartially to all, of whatever colour or degree.”1

These statements were summaries of an idea expressed many times by abolitionists during the war. The most eloquent and persistent spokesman for this revolution of racial equality was Wendell Phillips. His program of reconstruction, said Phillips early in 1862, was the creation of a nation in which there was “no Yankee, no Buckeye, no Hoosier, no Sucker, no native, no foreigner, no black, no white, no German, no Saxon; … only American citizens, with one law impartial over all.” Phillips wanted to destroy the aristocratic society of the Old South and replace it with a new social order based on equal rights, universal education, and the dignity of labor. He declared: “I hold that the South is to be annihilated. I do not mean the geographical South…. [I] mean the intellectual, social, aristocratic South—the thing that represented itself by slavery and the bowie-knife, by bullying and lynch law, by ignorance and idleness…. I mean a society which holds for its cardinal principle of faith, that one-third of the race is born booted and spurred, and the other two-thirds saddled for the first to ride…. That South is to be annihilated. (Loud applause)” This social revolution must be accomplished primarily by the freedmen. “I want the blacks as the very basis of the effort to regenerate the South,” said Phillips. “We want the four millions of blacks—a people instinctively on our side, ready and skilled to work; the only element the South has that belongs to the nineteenth century.”2

Most abolitionists realized that free Negroes were treated little better in the North than in the South. The revolution of equality, they knew, must embrace North as well as South. “No Abolitionist condemns our Northern oppression of negroes one whit less than he does Southern Slavery,” declared Sydney Gay in 1862. “North as well as South, this outraged people encounter DENIAL everywhere,” asserted Gerrit Smith in a ringing denunciation of racial discrimination in the North. “Even the noblest black is denied that which is free to the vilest white. The omnibus, the car, the ballot-box, the jury box, the halls of legislation, the army, the public lands, the school, the church, the lecture-room, the social circle, the table, are all either absolutely or virtually denied to him.”3

Abolitionists could not hope to revolutionize the southern social order without first improving the status of northern Negroes. Gilbert Haven stated the problem succinctly. When southerners observed “no recognition of the unity of man” in the North, he said, “when they see these, our brethren, set apart in churches and schools, or, if allowed to enter our churches, driven into the lowest seats; when they behold every avenue of honorable effort shut against them,—that no clerk of this complexion is endured in our stores, no apprentice in our workshops, no teacher in our schools, no physician at our sick-beds, no minister in our pulpits,—how can we reproach them for their sins, or urge them to repentance?”4

When the militant phase of abolitionism began in 1831 the status of northern Negroes was deplorable. Shut out from white schools and churches, forced to live in city slums and ghettos, denied equal civil and political rights, subject to Jim Crow legislation and degrading “black laws” in many states, confined to menial occupations, almost universally despised as members of an inferior race, the northern Negroes’ lot in 1830 was a harsh one. In some respects their status actually deteriorated in the next thirty years. The huge influx of immigrants in the 1840’s and 1850’s drove colored people out of many of their former occupations and subjected them to the mob fury of socially and economically insecure immigrants. Some of the western states made their black laws more severe between 1830 and 1860.

At the same time, however, northern Negroes made significant gains in other areas, especially in New England, the center of abolitionist influence. By a combination of moral suasion and political pressure, abolitionists and free Negroes helped to bring about the desegregation of most public schools in New England and the abolition of Jim Crow on New England stage coaches, horse cars, and railroads. Abolitionist efforts were partly responsible for the defeat of the Rhode Island constitution of 1842, which had established white manhood suffrage, and the substitution of a new constitution which granted Negro suffrage. Abolitionists registered their protests against “Negro pews” by withdrawing from churches that practiced this form of segregation and by joining or founding congregations which admitted Negroes on an equal basis. Abolitionist and antislavery lecturers almost singlehandedly ended segregated seating in many lecture halls by refusing to speak before segregated audiences. The Hutchinson family refused to sing before segregated groups. In many ways abolitionists tried to bear witness against the system of racial discrimination which prevailed in the antebellum North.

In 1860 Negroes enjoyed equal political rights in all the New England states except Connecticut. In New York, Negroes possessing property worth $250 could vote. In all other northern states colored men were denied suffrage.5 All but a handful of public schools in New England were open to both races. Public transportation in most of the North was nonsegregated. But Jim Crow still prevailed on the New York, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, and San Francisco streetcars. Public schools in most of the North outside of New England were segregated, and in some areas no public schools at all were open to Negroes. In several western states Negroes were subjected to severe legal discrimination and denied equal rights in the courts. In many parts of the North, including New England, Negroes were discriminated against in housing, employment, restaurants, hotels, and places of recreation.6

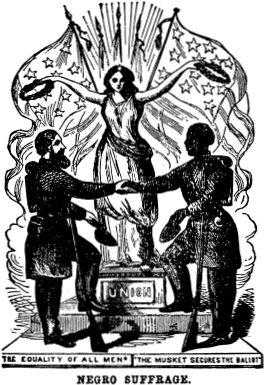

“Negro Suffrage.” From the Boston Commonwealth

With the outbreak of war, some abolitionists feared that the campaign for equal rights in the North might be buried by the confusion and excitement of armed conflict. “The laws respecting the colored man, in Iowa, Illinois, and other Western States, notwithstanding the predominance of Republican majorities, are disgraceful and proscriptive,” wrote a western abolitionist. “It seems to me that the work of the Anti-Slavery Society ought to be carried on unrelaxingly. Legislation of a just character needs to be inaugurated. It will not answer to trust these reforms to this war.” The Essex County (Massachusetts) Anti-Slavery Society resolved at the end of 1861 that “we still deem the mission of the Abolitionists unaccomplished so long as a … nominally free colored man is subjected to any proscription, political, educational, or ecclesiastical.”7 Stephen S. Foster declared in January 1862, that the object of the American Anti-Slavery Society was “not merely to destroy the form of slavery, but to destroy the spirit of oppression, which shows itself at the South, in the form of slavery, and at the North, in the bitter and relentless prejudice against color.” Later in the year a Boston Negro reminded abolitionists that there was still much work for them to do right in Boston, where Negroes suffered discrimination in housing, employment, and some restaurants.8

In 1861 Susan B. Anthony pronounced a severe indictment of racial discrimination in the North. The northern people were horrified by tales of southern cruelty to slaves, she said, “and yet, what better do we? While the cruel slave-driver lacerates the black man’s mortal body, we, of the North, flay the spirit.” Even when the northern Negro obtained an education, he found the doors to many vocations shut in his face. Miss Anthony declared that reconstruction of the nation on the basis of equality for all men must begin in the North. She concluded: “Let us open to the colored man all our schools, from the common District to the College. Let us admit him into all our mechanic shops, stores, offices, and lucrative business avocations, to work side by side with his white brother; let him rent such pew in the church, and occupy such seat in the theatre, and public lecture room, as he pleases; let him be admitted to all our entertainments, both public & private; let him share all the accommodations of our hotels, stages, railroads and steamboats…. Extend to him all the rights of Citizenship. Let him vote and be voted for; let him sit upon the judge’s bench, and in the juror’s box…. Let the North thus prove to the South, by her acts, that she fully recognizes the humanity of the black man.”9

Individually and in small groups, by private persuasion, precept, or example, abolitionists did what they could during the war to lessen prejudice and mitigate discrimination in the North. A Michigan abolitionist who owned a large farm told Garrison that he employed several Negro farmhands, paying them the same wages, serving them at the same table, and sleeping them in the same bunkhouse as his white laborers. Henry Cheever organized a “Freedom Club” in Worcester, containing men of both races, whose object was to break down the barriers between white and colored workingmen.10 William H. Channing, abolitionist chaplain of the U.S. House of Representatives, invited Negro minister Henry Highland Garnet to occupy his pulpit in the House chamber one Sunday morning in February, 1865. Channing considered this event an important step in the campaign against discrimination in the nation’s capital. At about the same time Charles Sumner presented Boston Negro lawyer John Rock as a candidate to argue cases before the Supreme Court. Chief Justice Chase accepted Rock and swore him in, making him the first Negro ever to be accredited as a Supreme Court lawyer. This affair was regarded by abolitionists as a symbol of the revolution in the Negro’s status since 1857, when Chief Justice Taney had denied the citizenship of black men.11

Abolitionists tried also to cleanse northern churches of segregation. It was not always an easy task. In 1863 the Reverend Horace Hovey, abolitionist pastor of the Congregational church in Florence, Massachusetts, preached that “the negro has the same right that we have … to obtain a first-rate education and to rise in social position according as he rises in worth; the same right to vote and to sit in legislative and congressional halls.” Fifteen or twenty of his parishioners took offense at these words and walked out of the church. But there were some encouraging signs of progress. Maria Weston Chapman rejoiced in 1863 that the Park Street Church in Boston had reversed its long-standing policy of refusing to rent pews to Negroes.12 Gilbert Haven succeeded in desegregating many New England Methodist churches, in expunging the word “colored” from the minutes of the New England Methodist Conference, and in securing admission of a Negro minister to the Conference as pastor of an integrated church.13

Education was another area in which abolitionists worked to promote desegregation wherever they were in a position to do so. Segregation had been abolished in Boston’s public schools in 1855 largely through the efforts of abolitionists and antislavery Republicans. During the war abolitionists extended their school desegregation efforts to New York. In 1863 Andrew D. White, antislavery Republican and future president of Cornell University, was elected to the New York legislature to represent the Syracuse district. Because of his teaching experience, White was appointed chairman of the Education Committee and given the task of codifying New York’s education laws. A statute of 1841 had authorized the establishment of segregated schools in any district that wished to maintain them. White wanted to repeal this statute and abolish school segregation in the state. One of his closest friends in Syracuse was Samuel J. May, the veteran abolitionist crusader. White asked May for information and arguments against segregation. May supplied him with abolitionist writings on the inherent equality of the Negro, reports of the success of integration in New England schools, and a long letter outlining the main arguments for desegregation. Separate schools for Negroes, wrote May, were “a perpetual imputation of fault, unworthiness or inferiority, which must tend to discourage and keep them depressed” even if the facilities were equal to those of white schools. Colored children should enjoy “not only equal educational privileges, but the same, as the white people enjoy.” The common schools were the nursery of the Republic, argued May, and the fostering of caste distinctions in the schools would create class and racial divisions in the nation which could prove fatal to democracy. The mission of America was “to show the world that all men, not white men alone, but all, of every complexion, language and lineage have equal rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness…. Let then our common schools, from the lowest to the highest grade, be equally open to the children of all the people.” The efforts of May and White were unavailing, however, and New York did not prohibit segregation in its public schools until nearly forty years later.14

In 1861 there were still five New England cities that maintained segregated public schools: Hartford and New Haven, Connecticut, and Providence, Newport, and Bristol, Rhode Island. Abolitionists and Negroes in Rhode Island kept up a steady antisegregation pressure on school officials, city councilmen, and state legislators. They petitioned these bodies repeatedly, arguing that segregation placed a stigma of inferiority on Negro children and that the colored schools were provided with inferior funds and equipment. In May 1864, abolitionists won a preliminary victory when the General Assembly’s committee on education recommended abolition of separate schools in Rhode Island. In 1865 the lower House passed a bill embodying this recommendation. But the Senate defeated the measure by a narrow margin, largely because of the determined opposition of Newport senators. Thomas Wentworth Higginson had moved to Newport after his discharge from the army in 1864 and was elected to the School Board in 1865. As a result of Higginson’s efforts, Newport abolished its separate schools in September 1865. With the opposition of Newport legislators thus removed, the Rhode Island legislature in 1866 outlawed school segregation in the entire state. Abolitionists rejoiced in the removal of “this last relic of slavery” from Rhode Island. The Connecticut legislature followed the example of its neighbor and abolished segregated public education in the Nutmeg State in 1868.15

Normal schools in New England were open to both races, but many of the private academies and preparatory schools were not. Abolitionists played an important role in desegrating two prominent New England private schools in 1865. John G. Whittier and Theodore Weld were instrumental in securing the admission of colored girls to Dr. Dio Lewis’ girls’ school in Lexington, Massachusetts, where Weld and his wife Angelina taught from 1864 to 1867.16 The energetic Rhode Island Quaker abolitionist, Elizabeth Buffum Chace, decided in 1865 that the refusal of the Friends’ school in Providence to admit colored applicants was a disgrace that could no longer be tolerated. Through her friend Dr. Samuel Tobey, a wealthy New England Quaker who was one of the main financial supporters of the school, Mrs. Chace obtained a promise from the trustees to admit henceforth all qualified applicants, regardless of race. The action of these two private schools paved the way for the lowering of the color bar at several other New England academies.17

More widely publicized than these school desegregation measures were the efforts to remove discrimination in the courts, transportation, and other areas. Charles Sumner was a leader of anti-discrimination activity at the national level. In 1862 he guided to Senate passage a bill to repeal an 1825 law barring colored persons from carrying the mail. Democrats and conservative Republicans defeated the measure in the House, but it finally passed both Houses and became law on March 3, 1865. In 1862 Massachusetts abolitionists called on Congress to enact legislation granting Negroes equal rights in federal courts. Sumner introduced a bill providing that in all proceedings of District of Columbia courts there would be no exclusion of witnesses because of race. The measure passed both Houses. In 1864 Sumner finally secured enactment of a law prohibiting the exclusion of witnesses from federal courts on grounds of race or color. During the war, Congress admitted Negroes to its visitors’ galleries for the first time. Many white persons in Washington complained that it was an insult to every white man in the land to admit “niggers” to the congressional galleries, and called down direful maledictions upon the heads of “Sumner and the nasty abolitionists” for perpetrating this vulgar act, but their complaints were of no avail.18

In 1863 Sumner and the abolitionists opened an attack on segregation and exclusion of Negroes from the horsecars and railroads of the District of Columbia. Supported by a series of militant editorials in the New York Tribune (probably written by Gay), Sumner introduced amendments to the charter renewal grants of several Washington companies prohibiting them from excluding or segregating passengers on account of race. Finally in 1865 Sumner obtained passage of a bill prohibiting segregation on every streetcar line in the District.19 Desiring to test the effectiveness of this statute, the venerable Sojourner Truth, ageless Negro abolitionist who was working among the freedmen at Arlington, rode on the horsecars of several Washington lines. One conductor tried to make her ride on the outside platform. She threatened to sue him if he persisted, and he gave in. Another conductor pushed her roughly against the door in an effort to eject her from the car, causing a painful injury to her shoulder. She had him arrested and caused him to lose his job. Soon after this a conductor was seen to stop his car unasked and beckon kindly to some colored women standing timidly in the street. The right of Washington Negroes to ride in the horsecars was henceforth unquestioned.20

Nowhere in the North were Negroes and abolitionists more hated than in New York City. Irish laborers feared economic and social competition from the black man and had little use for a war fought to free the slave. Sparked by the enforcement of the draft, New York’s immigrant and lower-class population rioted during four days of bloody mob violence in July 1863. The mob lynched Negroes in the streets and burned the Colored Orphan Asylum to the ground. The rioters attacked the offices of the New York Tribune and ransacked the homes of abolitionists and Republicans. New York police and federal troops finally brought the mobs under control.21

Abolitionists went immediately to work to get New York’s stricken Negro population back on its feet after the riots. The American Missionary Association disbursed temporary relief and assistance. Gerrit Smith contributed $1,000 to help the work. Abolitionists were unexpectedly aided in their efforts by New York City merchants, who organized a relief society and raised thousands of dollars for assistance and for the rebuilding of the orphan asylum. In fact, despite the murders and suffering, the riots in the long run helped to improve the status of New York Negroes. Angelina Weld reported two weeks after the uprising that a reaction against the Irish and in favor of colored people was setting in among the city’s middle and upper classes. Wealthy families discharged Irish servants and hired Negroes. The average middle-class New Yorker began to realize that he had been partly responsible for the murderous outrages against Negroes. All classes of white citizens had held Negroes in contempt, spoken disrespectfully of them, and refused to admit them to streetcars, schools, restaurants and hotels. Little wonder then that the lower classes mobbed and lynched them. A more kindly spirit toward colored people began to manifest itself in New York in the weeks and months after the draft riots.22

Taking advantage of this shift in public opinion, the three abolitionist newspapers in New York City (Independent, Anti-Slavery Standard, and Principia) plus the Tribune and the Evening Post inaugurated a campaign to abolish Jim Crow on all of the city’s street railroads. Most streetcar companies allowed Negroes to ride in their cars, but the Fourth Avenue and Eighth Avenue roads permitted their conductors to exclude colored people, and the Sixth Avenue company segregated them in special cars. Abolitionists contended that the railroads were common carriers and were required by law to provide transportation equally to everyone. They threatened to take the matter to court. The Fourth Avenue road finally began admitting Negroes to its cars in February 1864, but the other two companies still refused to change their policy. In June 1864, the controversy came to a head when the conductor of an Eighth Avenue car, aided by an Irish policeman, forcibly ejected the widow of a Negro sergeant who had been recently killed in battle. The Tribune exploded in anger: “It is quite time to settle the question whether the wives and children of the men who are laying down their lives for their country … are to be treated like dogs.” Public opinion was hostile to the railroad. The policeman who had helped eject the woman was reprimanded by his superiors. The city police commissioner prohibited his men from helping conductors eject Negroes from the cars. The Eighth Avenue road capitulated to the surge of public opinion and ended its exclusion of Negroes. A few days later the Sixth Avenue road likewise surrendered. All of New York City’s public transportation was thenceforth integrated.23

Philadelphia in 1860 had a larger Negro population than any other northern city. Several Philadelphia Negroes had amassed considerable wealth and resided in comfortable, even luxurious homes. Most colored residents of the City of Brotherly Love, however, lived in squalor and poverty in unsanitary slums. Philadelphia was a rigidly segregated city. Negro children attended separate schools when they attended any schools at all. Some of the city’s nineteen streetcar and suburban railroad companies refused to admit Negroes to their cars; those that did admit colored people forced them to ride on the front platform. Negroes seeking transportation in the city were often compelled to walk or hire an expensive carriage.24

This extreme Jim Crowism in transportation came under powerful attack by Philadelphia abolitionists. Garrisonian abolitionism was stronger in Philadelphia than anywhere outside New England. A large number of the city’s colored people were Garrisonians. Philadelphia’s Negroes also supported thriving organizations of their own, particularly the Social, Civil, and Statistical Association of Colored People, which sponsored lectures, provided legal assistance to Negroes, and served as a pressure group in behalf of the interests of all colored people. William Still, a prominent Philadelphia Negro, was leader of this Association and was also an official in the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society.25

The Colored People’s Association, the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, and the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society all maintained standing committees to work for the abolition of discrimination in Philadelphia’s transportation system. William Still inaugurated the militant phase of the antisegregation campaign in 1859 with a long letter to the press detailing the insults and hardships suffered by Negroes on Philadelphia’s street railroads. The letter was widely reprinted and focused national attention on the subject. In 1862 Still obtained the signatures of 360 prominent white Philadelphians, including all of the city’s leading abolitionists, to a petition requesting the Board of Presidents of the City Railways to end segregation on their lines. The board took no action on the petition, but from this time forward the anti-Jim Crow campaign grew in scope and intensity. The three abolitionist committees kept up the pressure by means of petitions, speeches, letters to the press, and private interviews with railroad presidents. In 1863 Still wrote an eloquent letter to the city’s leading newspapers, the Philadelphia Press, describing in detail the humiliation suffered by a Negro who tried to obtain transportation in the City of Brotherly Love. The letter was widely published. It appeared in the London Times, and was reported by Moncure Conway to have done more harm to the Union cause in England than a military defeat.26

The emergence of a national policy of arming Negroes to fight for the Union gave an important fillip to the antisegregation efforts. The antislavery press began to publish stories of wounded colored soldiers who had been ejected from Philadelphia horsecars. Sensing a change in public opinion, abolitionists and Negroes, now supported by the whole Republican press of Philadelphia, stepped up their struggle against segregation. In October 1864, a National Colored Men’s Convention met in Syracuse and urged the formation of state Equal Rights Leagues throughout the North to work for desegregation and Negro suffrage. The first (and strongest) such League was formed in Philadelphia, and its initial target was streetcar segregation. It joined in the growing outcry for an end to discrimination in Philadelphia transportation.27

William Still suggested to J. Miller McKim the idea of holding a mass meeting at Philadelphia’s Concert Hall to demand the abolition of Jim Crow. McKim used his contacts with leading Philadelphia Republicans and businessmen to arrange a meeting for January 13, 1865, sponsored by prominent white Philadelphians. The meeting adopted resolutions calling on the railroads to end their Jim Crow policy, and appointed a committee to negotiate with the railroad presidents. McKim and James Mott, secretary and president respectively of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, were two of the leading members of this committee. Their efforts obtained some immediate results. The Philadelphia and Darby Railroad, a suburban line, put an end to segregation on its trains. A few days later a streetcar company also abolished segregation, and another line began admitting Negroes to some of its cars. After a month the first company reported that because of integration it had lost white passengers and its revenue had declined; therefore it would henceforth allow Negroes only in special “Colored” cars. The Board of Railway Presidents took a public “poll” in the streetcars and announced that a majority of white Philadelphians still opposed integration. But McKim’s committee did not give up. They made a direct appeal to the mayor, a Democrat, who rebuffed them with the statement that he did not wish “the ladies of his family to ride in the cars with colored people.”28

Defeated at the city level, advocates of equal rights turned hopefully to the state legislature. There they found a staunch ally, Senator Morrow B. Lowry from northwestern Pennsylvania, who for six years had been urging passage of a state law to prohibit segregation in public transportation. Described by Garrison as “a most radical abolitionist, and reminding me alike of Gerrit Smith and Charles Sumner,” Lowry was a genuine crusader for equal rights.29 The State Senate passed Lowry’s bill by a close vote, but it was shelved in the House. Lowry persisted, and in March 1867, his bill finally passed both Houses and became law. It prohibited discrimination in every form of public transportation in the entire state of Pennsylvania. It was an impressive victory for equal rights, and to abolitionists and Negroes must go the main credit for the triumph. It was they who initiated the struggle and kept up the pressure; and it was an abolitionist who piloted the bill through the state legislature.30

Not content with the policy of arming Negroes in separate regiments, a few enthusiastic integrationists among the abolitionists called for the abolition of colored regiments and the complete integration of the army. “I want to sink the differences of race,” wrote Samuel Gridley Howe. “I do not believe in black colonies, or black regiments.” Gilbert Haven said, “We must abolish colored regiments…. A citizen, if he volunteers, should join what regiment he chooses; if he is drafted, those that most need his musket.”31 Such a policy, however, was too radical for the 1860’s. The enlistment of Negroes on any basis was a revolutionary step forward; full-scale integration of the armed forces would not come until nearly a century later.

In addition to the antidiscrimination measures described above, northern Negroes made other advances in civil rights during and immediately after the war. California abolished its laws excluding Negro testimony against whites in the courts in 1863. Illinois did the same in 1865, and repealed all the rest of her infamous “black laws” except the exclusion of Negroes from the polls. Chicago’s public schools were desegregated in 1865. In 1866 the Indiana Supreme Court declared unconstitutional the worst of that state’s black laws. In 1865 Massachusetts enacted the first comprehensive public accommodations law in American history, forbidding the exclusion of any person because of race or color from restaurants, inns, theaters, and places of amusement. The New York Tribune and Anti-Slavery Standard called for passage of a federal law to prohibit discrimination in public transportation. Such a law, said Sydney Gay, would be “a fit corollary to the Amendment which abolishes slavery.” Senator Henry Wilson introduced a bill in February 1865, providing for a fine of $500 against any railroad or steamship in the United States which discriminated against Negroes.32

The time was not yet ripe for such a sweeping national law, and Wilson’s bill was buried in committee. But the very fact that such a bill could be introduced in 1865 was an indication of the revolution in the status of colored men since 1861. Under the pressure of military necessity the Negro had been freed and given an opportunity to fight for the Union. He fought courageously and well, winning the grudging respect of millions of northern whites. The Negro’s contribution as a soldier combined with the patient, effective work of civil rights advocates won large gains for the northern Negro during the war. Black laws and discrimination in civil rights were slowly crumbling away and Jim Crow was gradually disappearing from many parts of the North. Race prejudice, however, remained powerful and discrimination continued to prevail in many walks of life. Negroes in 1865 could vote on equal terms with whites in only five states, and these states contained only 7 per cent of the northern Negro population. Negro suffrage would soon become the main issue of southern reconstruction, and so long as most northern states refused the ballot to black men, the North was in a false and stultifying moral position. Abolitionists appreciated this fact and kept up their agitation for equal suffrage in the North. Despite the preeminence of the southern problem during Reconstruction, the status of the northern Negroes continued to occupy much of the attention of abolitionists.

1 Independent, June 25, 1863; Moncure D. Conway, Testimonies Concerning Slavery (2nd ed., London, 1865), 131-32. For a brilliant discussion of the evolution of equal rights as a northern war aim, see C. Vann Woodward, “Equality: the Deferred Commitment,” in The Burden of Southern History (Vintage Books, New York, 1961), 69-87.

2 Speeches by Phillips published in Liberator, Apr. 25, May 23, Nov. 28, 1862.

3 New York Tribune, Mar. 21, 1862; Gerrit Smith to the editor of the New York Tribune, July 1, 1861, published in the Tribune, July 7.

4 Gilbert Haven, National Sermons, Speeches, and Letters on Slavery and Its War (Boston, 1869), 139.

5 In Ohio, men with a greater visible admixture of Caucasian than Negro genes could vote. In some respects, of course, this was a greater insult to the Negro than the denial of suffrage to all colored men.

6 For the best discussion of the status of northern Negroes before the Civil War and of the efforts of abolitionists to improve that status, see Leon F. Litwack, North of Slavery (Chicago, 1961). Most histories of the abolitionist movement and biographies of abolitionist leaders contain references to the attempts of abolitionists to secure equal civil and political rights for Negroes in the antebellum North. For additional descriptions of the condition of northern Negroes on the eve of the Civil War, see Anglo-African, Jan. 7, 1860; and Liberator, Oct. 5, 26, Nov. 2, Dec. 7, 1860, Jan. 4, Mar. 15, 1861.

7 N.A.S. Standard, June 22, 1861; Liberator, Dec. 27, 1861.

8 Liberator, Jan. 31, 1862, Aug. 15, 1862.

9 MS of speech, marked “1861,” in S. B. Anthony Papers, LC.

10 H. Willis to Garrison, June 20, 1861, Garrison Papers, BPL; Henry Cheever to Gerrit Smith, July 20, 1864, Smith Papers, SU.

11 Octavius B. Frothingham, Memoir of William Henry Channing (Boston, 1886), 316; Channing to L. M. Child, Mar. 8, 1865, published in Commonwealth, Mar. 25, 1865; New York Tribune, Feb. 9, 1865.

12 Horace C. Hovey to M. W. Chapman, July 15, 1864, Weston Papers, BPL; M. W. Chapman to Mary Estlin, Dec. 29, 1863, Estlin Papers, BPL.

13 William Haven Daniels, Memorials of Gilbert Haven (Boston, 1880), 151, 182; William G. Cochrane, “Freedom without Equality: A Study of Northern Opinion and the Negro Issue, 1861-1870,” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Minnesota, 1957, 294-96.

14 James M. Smith, “The ‘Separate But Equal’ Doctrine: An Abolitionist Discusses Racial Segregation and Educational Policy during the Civil War,” Journal of Negro History, XLI (April 1956), 138-47. This article publishes the letter from May to White, Mar. 11, 1864, which can be found in the Collection of Regional History, Cornell University. The public schools of Syracuse, a center of antislavery activity in upstate New York, had been desegregated for more than twenty years. In his report on the condition of Canadian Negroes, Samuel Gridley Howe observed that “the colored children in the mixed schools do not differ in their general appearance and behavior from their white comrades. They are usually clean and decently clad. They look quite as bright as the whites…. The association is manifestly beneficial to the colored children…. The appearance, and the acquirements of colored children in the separate schools, are less satisfactory.” Howe made a strong plea for school desegregation in the United States. Howe, The Refugees from Slavery in Canada West (Boston, 1864), 78-79.

15 Liberator, Sept. 6, 1861, Mar. 11, 18, 1864, Sept. 29, 1865; Commonwealth, Mar. 4, 18, 1865; N.A.S. Standard, Oct. 7, 1865, May 26, 1866; Higginson to Anna and Louisa Higginson, Apr. 19, 1874, Higginson Papers, HU; Irving H. Bartlett, From Slave to Citizen: The Story of the Negro in Rhode Island (Providence, 1954), 52-59; Special Report of the Commissioner of Education on the Condition and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Columbia … (Washington, 1871), 328, 334-35.

16 Dio H. Lewis to Whittier, Sept. 11, 1865, Whittier Papers, Essex Institute; Benjamin Thomas, Theodore Weld: Crusader for Freedom (New Brunswick, N.J., 1950), 253-57.

17 Albert K. Smiley to J. B. Smith, Sept. 5, 1865, E. B. Chace to Samuel Tobey, Sept. 15, 1865, Tobey to Mrs. Chace, Sept. 18, 1865, Smiley to J. B. Smith, Sept. 18, 1865, in Lillie B. C. Wyman and Arthur C. Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace (2 vols., Boston, 1914), I, 276-78.

18 McPherson, History of the Rebellion, 239-40, 242-43, 593; U.S. Statutes at Large, XII, 351, 407, XIII, 515; New York Tribune, Apr. 12, 1862, June 30, 1864; Liberator, June 27, 1862; Commonwealth, Sept. 27, 1862; Boston Advertiser, quoted in Liberator, Jan. 6, 1865; Anglo-African, Jan. 4, 1862.

19 McPherson, History of the Rebellion, 241-42, 593-94; U.S. Statutes at Large, XII, 805, XIII, 537; New York Tribune, Feb. 4, 11, 17, Mar. 1, 18, 1864; Liberator, Mar. 20, 1863; Commonwealth, Mar. 11, 1864.

20 Lillie B. C. Wyman, American Chivalry (Boston, 1913), 110-12.

21 Albon P. Man, Jr., “Labor Competition and the New York Draft Riots of 1863,” Journal of Negro History, XXXVI (1951), 375-405; New York Tribune, July 13-20, 1863; Angelina Weld to Gerrit Smith, July 28, 1863, Smith Papers, SU; Oliver Johnson to Garrison, July 16, 1863, Garrison to Johnson, July 25, 1863, Sarah Pugh to R. D. Webb, Aug. 11, 1863, Garrison Papers, BPL. In 1862 and 1863 there were anti-Negro riots in many northern cities, caused by real and potential labor competition between white and Negro workingmen. Williston Lofton, “Northern Labor and the Negro during the Civil War,” Journal of Negro History, XXXIV (July 1949), 251-73.

22 Mattie Griffith to Elizabeth Gay, Aug. 6, 1863, Gay Papers, CU; S. S. Jocelyn to Gerrit Smith, July 22, 1863, Gerrit Smith Papers, SU; Jocelyn to Lewis Tappan, July 30, 1863, Tappan Papers, LC; W. E. Whiting to Gerrit Smith, July 20, 1863, Angelina Weld to Smith, July 28, 1863, Smith Papers, SU; L. M. Child to Frank Shaw, July 27, 1863, Child Papers, Wayland Historical Society; Principia, Jan. 7, 1864.

23 George Cheever to Elizabeth Washburn, Aug. 5, 1863, Cheever Papers, AAS; New York Tribune, Aug. 4, 5, 7, 1863, June 21, 24, 30, 1864; Principia, Aug. 13, 1863; Independent, Jan. 21, 1864; Liberator, Mar. 4, 1864; Boston Commonwealth, June 24, 1864; N.A.S Standard, July 2, 9, 16, 1864. Quotation is from New York Tribune, June 21, 1864. Segregation on San Francisco’s street railroads was abolished by a district court ruling in October 1864. Liberator, Nov. 18, 1864, quoting San Francisco Bulletin, Oct. 3, 1864. In Cincinnati, however, Jim Crow in public transportation was not ended until after the war.

24 Ira V. Brown, “Pennsylvania and the Rights of the Negro, 1865-1887,” Pennsylvania History, XXVIII (Jan. 1961), 45-46; Liberator, Sept. 21, 1860; Twenty-Seventh Annual Report of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (Phila., 1861), 17.

25 Brown, “Pennsylvania and the Rights of the Negro,” op.cit., 49-50; Alberta S. Norwood, “Negro Welfare Work in Philadelphia, Especially as Illustrated by the Career of William Still, 1775-1930,” M.A. thesis, U. of Pennsylvania, 1931, 18-24; Larry Gara, “William Still and the Underground Railroad,” Pennsylvania History, XXVIII (Jan. 1961), 33-39.

26 Norwood, “William Still and Negro Welfare Work,” 52-60; William Still, A Brief Narrative of the Struggle for the Rights of the Colored People of Philadelphia in the City Railroad Cars (Phila., 1867), 3-10; Twenty-Seventh Annual Report of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, 17; Thirtieth Annual Report of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (1864), 23-24.

27 New York Tribune, Nov. 19, 1864; N.A.S. Standard, Oct. 15, Nov. 19, 1864, Jan. 14, 21, 1865; Liberator, Dec. 23, 1864, Jan. 6, 27, Mar. 24, 1865; Thirty-First Annual Report of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (1865), 17-18.

28 Still, Brief Narrative, 11-13; [Benjamin C. Bacon], Why Colored People in Philadelphia Are Excluded from the Street-Cars (Phila., 1866), 3-4; Thirty-Third Annual Report of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (1867), 26-27; Liberator, Jan. 27, 1865; Boston Commonwealth, Jan. 28, 1865; N.A.S. Standard, Jan. 28, Feb. 25, 1865; New York Tribune, Feb. 10, May 3, 1865; William Still to J. Miller McKim, Nov. 10, 1871, McKim Papers, NYPL.

29 Garrison to Helen Garrison, Nov. 5, 1865, Garrison Papers, BPL.

30 Brown, “Pennsylvania and the Rights of the Negro,” op.cit., 48-49; Lewis Tappan to Morrow B. Lowry, Jan. 18, 1865, Tappan letterbook, Tappan Papers, LC; Liberator, Feb. 3, Mar. 3, 1865; N.A.S. Standard, Apr. 1, June 3, 1865, Dec. 1, 1866, Feb. 23, Mar. 30, 1867; Report of the Committee Appointed for the Purpose of Securing to Colored People in Philadelphia the Right to the Street-Cars (Phila., 1867).

31 Howe to John Andrew, n.d., but sometime in spring of 1863, Andrew Papers, MHS; Haven, National Sermons, 405, 510. The United States Navy had always been integrated.

32 Commonwealth, Apr. 17, 1863, Nov. 10, 1866; Benjamin Quarles, The Negro in the Civil War (Boston, 1953), 313; New York Tribune, Feb. 6, 10, 1865; Special Report of the Commissioner of Education … (Washington, 1871), 343; Milton R. Konvitz, A Century of Civil Rights, with a Study of State Law Against Discrimination, by Theodore Leskes (New York, 1961), 155; Independent, Aug 3, 1865; N.A.S. Standard, Feb. 11, 1865. Gay’s statement from New York Tribune, Feb. 5, 1865.