EDUCATION AND CONFISCATION: 1865-1870

EDUCATION AND CONFISCATION: 1865-1870XVII  EDUCATION AND CONFISCATION: 1865-1870

EDUCATION AND CONFISCATION: 1865-1870

ABOLITYONISTS played an important part in the efforts to bring education and land to the freedmen. Garrison noted at the end of 1864 that emancipation would meet the southern Negroes “just where slavery leaves them—in need of everything that pertains to their physical, intellectual, and moral condition.” Here was a vast field for philanthropic effort, and Garrison urged his fellow abolitionists to fulfill their obligations to the freed slaves. The Anti-Slavery Standard asserted that reconstruction of the South “must be social as well as political…. It must reach to the very groundwork of social order.” The freedmen would have to be prepared for their new rights and responsibilities as citizens. “The duty of abolitionists to their clients will not cease with the technical abolition of slavery,” said the Standard. “These [Freedmen’s] Relief Associations prefigure the work that will remain to be done—the finishing of Emancipation and the perfecting of Reconstruction through Education.”1

In 1864 an abolitionist army officer stationed in Louisiana issued an appeal for northern teachers to instruct the freedmen. He wanted “ABOLITIONISTS! dyed with the pure dye—men who dare face this miserable, wheedling conservatism, and do something to merit at least the prevalent epithet nigger on the brain’ ”2 Of the several thousand northerners who went South to teach the freedmen during the war and reconstruction, a majority were probably abolitionists. Some teachers, of course, were motivated primarily by a desire for a change of climate, adventure, or by religious zeal, but most of them hoped to bear witness to their abolitionist faith by aiding the Negro in his transition to freedom. The correspondence of teachers was filled with references to their antislavery backgrounds. Several abolitionists devoted the rest of their lives to the southern Negro. Laura Towne, for example, founded the Penn School on St. Helena Island, South Carolina, in 1862 and remained there until her death in 1901. Sallie Holley and Caroline Putnam, old-line Garrisonian abolitionists from upstate New York, started a school for the freedmen at Lottsburgh, Virginia, in 1868. Miss Holley remained there until her death in 1898, and Miss Putnam was still instructing the Negroes of Lottsburgh in 1907. These examples of philanthropic longevity could be multiplied many times.3

Abolitionists predominated not only among the teachers of the freedmen but among the officers of the freedmen’s aid societies as well. Professor Henry Swint found that of the 135 leading officials of the freedmen’s societies, nearly half had been abolitionists, and many of the remainder had been active to a lesser degree in the antislavery movement. A few prominent abolitionists formed the backbone of the whole freedmen’s aid movement. J. Miller McKim served as the corresponding secretary (chief executive officer) of the American Freedmen’s Union Commission, which comprised all the secular freedmen’s societies from 1866 to 1869. George Whipple and Lewis Tappan, secretary and treasurer respectively of the American Missionary Association, were the chief officials of this largest of the evangelical freedmen’s aid societies. Levi Coffin was general agent of the Western Freedmen’s Aid Commission. John W. Alvord was superintendent of education for the Freedmen’s Bureau from 1865 to 1870. Reuben Tomlinson, H. R. Pease, and Edwin Wheelock served as state superintendents of education in South Carolina, Mississippi, and Texas during Reconstruction.4

Abolitionists were active at every level of the drive for education of the freedmen: organizing auxiliary societies, soliciting funds, lecturing, recruiting teachers, writing textbooks, and founding schools in the South. Samuel J. May devoted much of his time between 1863 and 1869 to organizing and administering the Syracuse Freedmen’s Aid Society, an auxiliary of the New York association. His cousin Samuel May, Jr., formed an auxiliary of the New England Freedmen’s Aid Society in Leicester, Massachusetts. Lydia Maria Child wrote a brief history of the Negro, entitled The Freedmen’s Book, to dramatize the heroes of the race and inculcate honesty, courage, and morality in Negro children; this book was used as a primer and textbook in freedmen’s schools. John G. Fee, one of the founders of Berea College, organized several schools, hospitals, and churches for the freedmen in his native Kentucky. As corresponding secretary of the New England Educational Commission for the Freedmen, a Baptist society, abolitionist Joseph Parker made several trips to the South and organized many freedmen’s schools. Elected a bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1872, abolitionist Gilbert Haven was stationed in Atlanta for eight years, where he brought new energy to the work of the Methodist Freedmen’s Aid Society and helped found Clark University. These are only a few examples of the activities of abolitionists at every level of the freedmen’s aid movement.5

One instance of abolitionist organization of southern schools deserves special mention. In February 1865, Union troops marched into Charleston, accompanied by James Redpath, reporter for the New York Tribune. Colonel Woodford seized all school buildings and appointed Redpath superintendent of public instruction. Within ten days Redpath had secured teachers, textbooks, and students. On March 4 he formally opened the schools to 1,200 freedmen and 300 white children. Negroes and whites were taught in the same building but segregated by classroom. Teachers were paid and textbooks supplied by northern freedmen’s aid societies. Within a few weeks the children of Charleston were off the streets and in school. By the end of March there were 3,114 children of both races in the schools. Most of the teachers were natives of Charleston: 74 of the 83 teachers, including 25 Negroes. By the end of May there were more than 4,000 pupils studying under 34 northern and 68 native southern teachers in 9 day schools and 5 night schools. Redpath returned North in June, followed by the praises of Charlestonians, army officers, and abolitionists for his efficient reorganization of Charleston schools.6

Another abolitionist who accomplished a great deal as an educator and social worker among the freedmen was Josephine Griffing. During the war thousands of freedmen flocked into Washington. Appalled by the miserable living conditions of these people in disease-ridden slums, Mrs. Griffing became general agent of the National Freedmen’s Relief Association of the District of Columbia in 1863. She distributed food and clothing and established vocational schools to teach new skills to freed men and women. In a period of two years—1865 to 1867—she found homes and employment in the North for more than 7,000 Washington Negroes. Thereafter she continued to send three or four hundred freedmen North every year for several years.7

Despite her efforts the freedmen continued to pour into the District faster than she could find homes for them in the North. Unskilled and unemployed, these people became a grave social problem and their miserable hovels an eyesore and a danger to public health. Especially serious was the problem of aged or crippled freedmen, who had almost no hope of future rehabilitation. The task seemed hopeless, but Mrs. Griffing continued to work undauntedly: she distributed private and public relief, and visited Negroes in their homes. In 1865 she was appointed sub-assistant commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau in the District of Columbia. When the Bureau proposed to reduce rations at the end of 1865 to avoid encouraging pauperism and idleness, she protested vigorously and gave several lectures publicizing the destitute condition of many freedmen in the capital. The aged and crippled Negroes could not support themselves, she declared, and the able-bodied men could not find work. Her lectures aroused considerable attention and controversy. Democrats cited the poverty and disease of Washington Negroes as proof that they had been better off in slavery. Some abolitionists were unhappy with Mrs. Griffing’s disclosures, fearing that they would only confirm the popular image of the shiftless, helpless Negro. General Howard dismissed her from the Freedmen’s Bureau because of her protests against Bureau policy. Yet Mrs. Griffing’s portrayal of conditions in the District was essentially accurate, and the Bureau was compelled to renew the distribution of rations to needy freedmen.8

Mrs. Griffing continued to serve as a one-woman welfare agency for Washington Negroes until her death in 1872. She was on good terms with radical Republican leaders in Congress. Every year she appeared before congressional committees and tried to wheedle more money out of them for relief. She urged the creation of public works programs in Washington to alleviate unemployment.9 Mrs. Griffing remained a target of criticism from certain Republican quarters. In 1870 Horace Greeley charged that her activities among the freedmen had done them great injury. “They are an easy, worthless race, taking no thought for the morrow, and liking to lean on those who befriend them,” Greeley told Mrs. Griffing. “Your course aggravates their weaknesses, when you should raise their ambition and stimulate them to self-reliance.” In an angry reply, Mrs. Griffing pointed out that she helped only those who could not help themselves. She had found work for many of the able-bodied, and her relief efforts were directed toward “those broken-down aged slaves whom we have liberated in their declining years, when all their strength is gone, and for whom no home, family, friendship, or subsistence is furnished.” If it was a “great injury” to help these people, then “there is no call for alms-house, hospital, home, or asylum in human society.” Criticism such as Greeley’s was exceptional, however. Most observers praised Mrs. Griffing for her herculean labors and steadfast humanitarianism. Senator Benjamin Wade told her in 1869, “I know of no person in America who has done so much for the cause of humanity for the last four years as you have done. Your disinterested labors have saved hundreds of poor human beings, not only [from] the greatest destitution and misery, but from actual starvation and death.”10

Whether serving as organizers, administrators, teachers, or social workers, abolitionists were in the forefront of efforts to educate and rehabilitate the freedmen. Their contribution was recognized by a speaker at the National Education Association meeting in 1884: “Those very men, extremists, enthusiasts, ‘fanatics,’ who had formed the backbone of the abolition movement … became the dauntless leaders of an educational movement which was the natural sequel and supplement of their first crusade.”11

The main purpose of freedmen’s aid was to bring the rudiments of education to illiterate Negroes. “If the blacks are kept in ignorance they can be subjected to a system of serfdom,” wrote J. Miller McKim. “If we enlighten them they are secure against the machinations of their old enemies—to which they will always be subject until educated.” McKim proclaimed repeatedly that education was necessary to equip the freedmen for the rights and responsibilities of citizenship. “Democracy without the schoolmaster is an impossibility,” he said. “Universal suffrage without universal education would be universal anarchy.”12 An element of cultural imperialism also entered into the thinking of some educators. The New England Freedmen’s Aid Society announced in 1865 that “New England can furnish teachers enough … to make a New England of the whole South; God helping, we will not pause in our work until the free school system … has been established from Maryland to Florida, and all along the shores of the Gulf.”13

The Freedmen’s Bureau was an important partner of the freedmen’s aid societies in the work of educating southern Negroes. The Bureau extended its benevolent protection over all educational activities in the South. It provided school buildings for the societies and transportation allowances for teachers. It systematized the record-keeping and reports of the societies. The state superintendents of education of the Bureau worked closely with officials and teachers of the freedmen’s societies. General Oliver O. Howard, head of the Bureau, was in complete sympathy with the purposes of the aid societies and established cordial relations with their leaders. As a devoted Congregationalist Howard was particularly close to the leaders of the American Missionary Association. The A.M.A. also enjoyed the special friendship of John W. Alvord, superintendent of education of the Freedmen’s Bureau, who had been associated with the evangelical wing of the abolitionist movement before the war.14

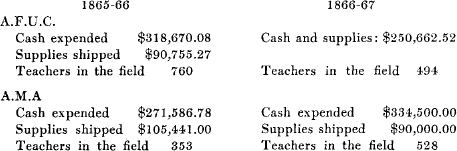

Under the leadership of J. Miller McKim, the regional secular freedmen’s societies were merged into a loose national federation in the fall of 1865, known as the American Freedmen’s Aid Commission (A.F.A.C.). Officials of the freedmen’s associations were happy with the progress of their work in 1865-1866. Excluding night schools and Sunday schools, the societies operated a total of 975 schools with 1,405 teachers and 90,778 pupils during the school year of 1865-66. Of this total the A.F.A.C. supplied 760 teachers and instructed approximately 50,000 pupils. The A.M.A. sent 353 missionaries and teachers into the field who had more than 20,000 students under their charge. The remainder of the schools were operated by independent evangelical associations.15

Teachers of the freedmen were confronted by many difficulties. In the early years of freedom the Negroes moved about a great deal and the school population was highly transient. Attendance was irregular and seasonal because so many Negro children had to work in the fields at planting and harvest time. The children came from a cultural environment almost entirely devoid of intellectual stimulus. Many of them had never heard of the alphabet, geography, or arithmetic when they first came to school. Few of them knew their right hand from their left, or could tell the date of their birth. Most of them realized only vaguely that there was a world outside their own plantation or town. The only contact they had with such mysteries was during their few hours in school a few months of the year. Progress was slow under such circumstances, but there were compensating factors. The freedmen had an almost passionate desire to learn to read and write, and children laboriously taught their parents the alphabet and multiplication tables during their spare time. Teachers invariably testified that despite their disadvantages in background, training, and environment, Negro children learned to read almost as well and as rapidly as white children.16

The problems faced by the teacher in the classroom were often less severe than those confronting her in the community. Many southern whites did not take kindly to the idea of Yankee “schoolmarms” instructing their former slaves. Some southern communities accepted the inevitability of Negro education and cooperated with the northern teachers. In most places, however, the white people regarded the Yankee teachers as aliens come to instill ideas of political and social equality into the heads of Negroes. Some southerners considered education of the Negro a harmful waste of time. “To talk about educating this drudge is to talk without thinking,” asserted the Paducah (Kentucky) Herald. “Either to ‘educate,’ or to teach him merely to read and write, is to ruin him as a laborer. Thousands of them have already been ruined by it.”17 Where the whites felt this way the teachers were sometimes insulted, beaten, and their schoolhouses burned. Southern contempt for the “nigger teacher,” however, usually took the milder form of social ostracism. White teachers frequently found it impossible to get room and board in white southern homes, and native whites would deliberately snub the teachers socially.

Even in southern communities that favored Negro education the Yankee teachers were regarded with a certain amount of suspicion. In the spring of 1867 Anna Gardner, teacher of a freedmen’s school in Charlottesville, Virginia, asked J. C. Southall, local newspaper editor and friend of Negro education, if he would print some diplomas for her school without charge. Southall replied that he would print them if he could be satisfied that the school confined itself to the ordinary rudiments of education. But he suspected that “you instruct them in politics and sociology; that you come among us not merely as an ordinary school teacher, but as a political missionary; that you communicate to the colored people ideas of social equality.” Even if she did not actually teach these things in the classroom, “you may, by precept and example, inculcate ideas of social equality with the whites among the pupils of your school and the colored people generally.” Such ideas were “mischievous, … tending to disturb the good feeling between the two races.” Therefore Southall refused to print the diplomas. Anna Gardner sent him a blunt reply: “I teach in school and out, so far as my influence extends, the fundamental principles of polities’ and ‘sociology,’ viz.:—‘Whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so unto them.’ ” Anna Gardner’s statement typified the attitude of many teachers, who did indeed practice “social equality”; and after the passage of Negro suffrage most of them taught Republican politics as well. Consequently relations between the Yankee teachers and a majority of southern whites remained somewhat strained as long as the schools existed.18

Another difficulty confronting the freedmen’s aid enterprise was descriptions by newspaper correspondents, travelers, and so on, of the degraded, ignorant, and destitute condition of many freedmen. Such reports were gleefully picked up by the Democratic press and cited as proof of the Negro’s worthlessness. In 1866 an official of the Freedmen’s Bureau made a speech describing the freedmen as “ignorant, degraded, indolent, sensual, false, far below what I had supposed.” The London Times published the speech. English friends of the freedmen wrote in alarm to J. Miller McKim telling him that such stories had a tendency in England to discourage contributions to freedmen’s aid. McKim replied that the freedmen were indeed degraded. That was why they needed assistance and education. McKim told the British friends of the freedmen: “Of course the blacks are to a degree just what Major Lawrence represents them; and just what anyone of common sense must a priori know them to be. Among the least of slavery’s evils are the manacles which it fastens on the limbs and the stripes which it inflicts on the backs of its victims. Our ‘zeal’ against it & in behalf of its injured subjects is kindled by the fact that its iron enters the soul—darkens the mind—dulls the intellect—perverts the affections—chokes the aspirations—and does every thing it can toward making the black man in fact what it has made him in law: a chattel…. The victims of the slave-system are ‘degraded’; therefore it is that we labor to lift them up.” The freedmen were actually less degraded than abolitionists had expected, said McKim. They had shown marked progress and gave every sign of susceptibility to improvement and education. The present backward condition of the freedmen, he concluded, should stimulate their friends to greater effort rather than cause them to despair for the future of the race.19

The freedmen’s aid enterprise encountered hostility not only from its enemies but from those who should have been its friends. During the war Phillips and other abolitionists had criticized the aid societies for their paternalism (see Chapter VII). When at the end of the war the Garrison wing of the American Anti-Slavery Society suggested that abolitionists should dissolve their organizations and continue their work for the Negro in the freedmen’s societies, Phillips renewed his criticism. He conceded that the freedmen’s associations were “doing a good work,” but it was a work of charity, an “old clothes movement” and “not the work of an Abolitionist.” Frederick Douglass told J. Miller McKim:

“I have my doubts about these Freedmen’s Societies. They may be a necessity of the hour and as such may be commended; but I fear everything looking to their permanence. The negro needs justice more than pity; liberty more than old clothes; rights more than training to enjoy them. Once give him equality before the law and special associations for his benefit may cease. He will then be comprehended as he ought to be, in all those schemes of benevolence, education and progress which apply to the masses of our Countrymen every where. In so far as these special efforts shall furnish an apology for excluding us from the general schemes of civilization so multitudinous in our country they will be an injury to the colored race. They will serve to keep up the very prejudices, which it is so desirable to banish from the country.”20

McKim and other proponents of freedmen’s aid resented these disparagements. McKim thought it more important to prepare the freedmen for the rights and duties of citizenship than to agitate for those rights in the abstract. “The Freedmen’s movement … is not an eleemosynary movement; not an old clothes movement; not a movement merely to relieve physical want & teach little negroes to read,” he declared. “It is a reconstructive movement. It is to reorganize Southern Society on a basis of impartial liberty. It is to remodel public opinion in regard to the black man by fitting him for [the responsible exercise of equal rights]…. It is a movement established and conducted in the interests of civilization.”21

While the intramural abolitionist debate over the merits of freedmen’s aid societies continued, an important development was taking place within the secular freedmen’s associations. In November 1865, representatives of the A.F.A.C. and the American Union Commission met to discuss the possibility of merging the two organizations. The American Union Commission had been formed in 1864 to give aid to Unionist refugees, mostly whites, in the South. The leaders of this Commission and of the A.F.A.C. believed that they could prosecute their work more efficiently if their organizations were united. The merger was approved on January 31, 1866. The name of the new association was the American Freedmen’s and Union Commission (the “and” was dropped in May 1866). The objectives of the new Commission were relief and education of blacks and whites alike in the war-torn South.22

Some of the auxiliary societies of the A.F.A.C. were opposed to the merger on the ground that it would divert too large a share of their limited resources to the education of southern whites. McKim worked hard to overcome this opposition. To a Pittsburgh abolitionist he wrote that “we can do more for the freedmen on the broad basis of man than of freed man or black man. We who go against class legislation & color distinctions—shall we legislate for a class—give preference to a color?” Was not the poor white southerner also a victim of slavery, McKim asked a Philadelphia abolitionist who opposed merger? “Shall we denounce President Johnson & his Congressional confreres for not legislating and administering the Government without respect to color, and yet ourselves … minister with regard to color?” McKim’s arguments finally prevailed, and by May 1866, all the auxiliary societies had ratified the new constitution of the American Freedmen’s Union Commission (A.F.U.C.). McKim became corresponding secretary of the new Commission, and Lyman Abbott, former secretary of the American Union Commission, became recording secretary of the merged organization. Abbott also edited the Commission’s monthly journal, the American Freedman,23

The issue of school desegregation soon confronted the A.F.U.C. The Commission made its position on this question perfectly clear in the first issue of its monthly journal. “[We] insist … that both races shall enjoy the same rights, immunities, and opportunities,” declared the American Freedman. “Our Commission is pledged to the maintenance of the doctrine of equal rights…. It took America three-quarters of a century of agitation and four years of war to learn the meaning of the word ‘Liberty.’ God grant to teach us by easier lessons the meaning of the words ‘equal rights.’ ” The constitution of the A.F.U.C. declared that no person would be excluded from the Commission’s schools because of race or color. The executive committee conceded that this integration policy “will produce difficulties in the South.” Nevertheless integration was “inherently right” and the Commission would never “shut out a child from our schools because of his color.”24

The constituent societies faithfully carried out the policy of desegregation. The New England Society, for example, instructed its teachers to admit white children “on precisely the same footing, and no other, with blacks; that is to say, they are to occupy the same rooms, recite in the same classes, and receive the same attention as the blacks. You cannot control public opinion outside of the school but, within its limits, you must secure entire respect from every pupil to every other.”25 The A.M.A. had always adhered to a desegregation policy, and most of the other evangelical societies did the same. In practice, however, few whites attended the freedmen’s schools. Elizabeth Botume, a teacher in South Carolina, told of two white girls who came to her school because there was no other school within a reasonable distance of their home. The children were happy, but after two months they suddenly stopped coming. Miss Botume visited their mother to learn the reason for their withdrawal. The mother “confessed the Southern white people had ‘made so much fuss’ because she allowed the children to go to a ‘nigger school,’” reported Miss Botume, that “she felt obliged to take them away.” The mother told Miss Botume, “I would not care myself but the young men laugh at my husband. They tell him he must be pretty far gone and low down when he sends his children to a ‘nigger school.’ That makes him mad, and he is vexed with me.” To avoid family quarrels she withdrew the children. In the term ending June 30, 1867, there were 111,442 pupils in schools operated by the freedmen’s societies, of whom only 1,348 were white.26

Abolitionists were delighted by the strong equal rights and integrationist position of the A.F.U.C. There was a noticeable decline in radical abolitionist criticism of the freedmen’s aid movement in 1866. Several speakers at the annual meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society praised the good work of the freedmen’s associations, and the Society adopted a resolution expressing its gratitude to “the devoted, most efficient, and inexpressibly important labors” of the freedmen’s teachers.27

But there was still some friction between the Phillips wing of abolitionism and the freedmen’s aid societies. Both groups were competing for financial support from the same class of northern people, The competition for funds erupted into a major quarrel in 1867 over the issue of the Jackson bequest. When Francis Jackson died in 1861 he left a trust fund of $10,000 to the antislavery cause. The money did not become available until 1867, two years after the abolition of slavery. Both Garrison and Phillips were on the board of trustees of the Jackson fund, and a dispute arose between them over the disposition of the legacy. Phillips claimed the money for the American Anti-Slavery Society on the ground that the Society’s campaign for Negro suffrage was a direct continuation of the antislavery movement. Garrison wanted the $10,000 for the New England branch of the A.F.U.C., arguing with equal assurance that freedmen’s aid was the logical heir of the abolitionist crusade. The two sides compromised in January 1867, and assigned half the legacy to freedmen’s aid and half to the American Anti-Slavery Society. But when Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts two months later, Garrison changed his mind and claimed all the money for the freedmen again. The enactment of Negro suffrage, he maintained, completely obviated the need for an antislavery society. Phillips disagreed, and the board of trustees was unable to reach agreement on the disposition of the legacy. The matter went to the Massachusetts Supreme Court, which decided in Garrison’s favor. Phillips was deeply angered by the decision and attacked Garrison and his supporters sharply in a series of Standard editorials. Garrison replied in kind. Abolitionists ranged themselves on either side of the quarrel and the whole affair became intensely bitter. Garrison and Phillips broke off personal and social relations for two years, and for a long time several of Phillips’ old abolitionist friends passed him on the street without speaking. The upshot was a partial revival of the hostility of Phillips and some of his associates toward the freedmen’s aid societies.28

The A.F.U.C. began to break up almost as soon as it was formed. Religious factionalism was the main cause of its downfall. The American Missionary Association and other evangelical freedmen’s aid societies required their teachers to be Christian missionaries as well as instructors. The evangelical associations believed that purification of the soul was as important as enlightenment of the mind. There was a sharp cleavage between the secular educational philosophy of the A.F.U.C. and the evangelical zeal of the A.M.A. This cleavage was essentially a continuation of the prewar rift between Garrisonian and evangelical abolitionists. Garrisonians predominated among the abolitionist element in the A.F.U.C., and the leadership of the A.M.A. was the same as the leadership of the prewar evangelical abolitionists.

From the outset of the freedmen’s aid movement there was competition between the secular societies and the A.M.A., especially in the matter of raising money in the North. In 1866-1867 the differences between the two groups came to a head. The A.M.A. declared that a freedman’s education would not be complete unless he was “imbued with the principles of evangelical religion.” Teachers of the A.F.U.C., on the other hand, were told that they were not “missionaries, nor preachers, nor exhorters” and instructed “not to inculcate doctrinal opinions or take part in sectarian propagandism of any kind.” The A.F.U.C. accused the A.M.A. of conducting “parochial schools” and of placing proselytism above education. Such statements by leaders of the eastern wing of the A.F.U.C. precipitated a crisis in the organization. The western branches of the A.F.U.C. had always required their teachers to be practicing Christians. Angered by the aggressive secularism of the eastern leaders, the Cincinnati branch withdrew from the A.F.U.C. in 1866 and was absorbed by the A.M.A. It was followed by the Cleveland branch in 1867 and the Chicago branch in 1868.29

The result of these withdrawals was a sharp decrease in the strength of the A.F.U.C. The A.M.A. had several advantages in its competition with the secular societies. In the first place it was an older organization with well-established sources of income. As a missionary society it could rely on consistent church support while the A.F.U.C. was forced to depend on the North’s short-lived philanthropic enthusiasm for education of the freedmen. Secondly, the A.M.A. enjoyed a greater degree of cooperation from the Freedmen’s Bureau than did the secular societies. General Howard and the Reverend Alvord were devoted Congregationalists. They sympathized with the A.M.A.’s philosophy of religious education. In many small ways the Freedmen’s Bureau extended more assistance to the A.M.A. than to the secular societies, causing anger and frustration among some officials of the A.F.U.C. Lastly, A.M.A. teachers were often able to establish a closer rapport with the freedmen because their evangelical piety was more akin to the Negro’s own religious experience than was the secularism of A.F.U.C. teachers.30 The declining strength of the A.F.U.C. in relation to that of the A.M.A. is revealed by a glance at the statistics:

The expenditures and number of teachers of the A.F.U.C. continued to decline in subsequent years while those of the A.M.A. remained steady for the rest of the decade.31

The competition of evangelical associations was not the only reason for the decline of the A.F.U.C. From 1864-1866 a great many people contributed to freedmen’s aid who were not deeply concerned about uplifting the Negro but who gave because it was the most “deserving” charity of those years. But in 1866 there was a slackening of popular interest in the movement. As early as 1865 one Gideonite commented on “the lethargy creeping over our community on this subject…. The feeling is somewhat general that the negro must make the most of his chances and pick up his a, b, c’s as he can.” All of the secular societies were forced to retrench during 1866-1867. The American Freedman noted in April 1867, that “the enthusiasm which accompanies a new movement, one especially which appealed so strongly to philanthropic and humane considerations as did this during the desolations of war, has somewhat passed away and left as its supporters only those who are attached to it by cardinal and well-considered principles.”32

In 1868 the executive committee decided to dissolve the A.F.-U.C. The activities of the Commission had decreased to the point where the constituent societies could carry on the work more efficiently by themselves. Dissolution of the A.F.U.C. was accomplished in 1869. The New York and Pennsylvania societies disbanded in the same year. The only secular societies remaining in existence after 1869 were the Baltimore and New England associations. The Baltimore society was absorbed by the city’s public school system in 1871. The New England society continued to support a few normal schools in the South until 1874, when it finally disbanded. The A.F.U.C. never fulfilled the grand hopes of its founders, but it accomplished a great deal for the education of southern freedmen. During their existence the secular freedmen’s aid societies spent nearly $3,000,000 on southern education and brought the rudiments of learning to more than 150,000 freedmen.33

Most important of all, however, the freedmen’s societies helped to lay the foundations of public education in the South. When the reconstructed state governments established their public school systems in the years 1868 to 1870, several of the freedmen’s schools were taken over directly by the state boards of education. Many of the teachers of the South’s new public schools had been educated by the northern freedmen’s associations. In several southern states, officials of freedmen’s aid societies drafted the public school legislation and served as the first superintendents of education. The public school system in the South was hardly in a flourishing condition when the A.F.U.C. disbanded in 1869, but the secular societies had run out of money, and making a virtue of necessity they proclaimed that the spread of public education in the South had ended the need for a northern freedmen’s commission.34

The financial inability of the South to support an efficient public school system, however, and the takeover of several state governments by conservatives unfriendly to public education sparked a movement for federal aid to education in the early 1870’s. In 1869 the new conservative government of Tennessee repealed the statewide compulsory school law, leaving the question of public education to the option of individual counties. All the state’s public schools for Negroes except those in Memphis and Nashville soon closed down. Caroline Putnam, a veteran abolitionist teaching the freedmen in Lottsburgh, Virginia, reported in 1870 that Virginia’s property tax for schools was unpopular with landowners. The new conservative governor had promised that the tax law would not be enforced. Caroline Putnam urged federal action to compel southern states to maintain a system of universal public education open to both races.35 In 1870 Congressman George F. Hoar of Massachusetts introduced a bill to establish public schools by national authority in states that failed to do it themselves. Senator W. T. Willey of West Virginia sponsored a bill for the distribution of the proceeds of public land sales among the states to help finance public schools. Abolitionists gave their support to these measures, and both Houses at different times passed different versions of them, but the bills never came to final passage. Abolitionist hopes for an efficient public school system for both races in the South were doomed to disappointment.36

During the war and early reconstruction years the freedmen’s aid societies concentrated almost entirely on elementary education. This emphasis was designed to make literate a large body of people recently emancipated and soon to be enfranchised. But this policy proved very expensive, and did little more than dent the crust of southern illiteracy. At no time were more than 10 per cent of the freedmen of school age attending the societies’ schools. Officials of the freedmen’s associations realized by 1866 that the establishment of normal schools and colleges to train Negro teachers would be a more effective use of their limited resources. The movement toward normal schools came after the decline of the A.F.U.C. had set in, and the secular societies never supported more than six or eight small normal schools in the South. But the A.M.A. and other evangelical societies established a large number of normal schools and colleges. The A.M.A. was the pioneer in Negro higher education in the South. Between 1866 and 1869 the Association founded seven chartered institutions, all of which were called colleges, although they were at first little more than high schools: Berea College (founded in 1855 and reopened in 1866), Fisk University, Atlanta University, Hampton Institute, Talladega College, Tougaloo College, and Straight University. The A.M.A. also aided in the establishment of Howard University. Some of these schools are today among the best southern universities for Negroes. By 1876 the A.M.A. was also operating 14 nonchartered normal and high schools in the South. As early as 1869 there were 314 teachers trained in A.M.A. institutions teaching in southern schools. It was estimated in 1873 that graduates of A.M.A. normal schools and colleges were teaching 64,000 pupils in southern schools; by 1879 this number had risen to 150,000.37

The other denominational societies were not far behind the A.M.A. in founding institutions of higher learning for Negroes in the South. In 1879 there were 39 normal schools, colleges, and theological seminaries and 69 schools of lower grade supported by northern churches and missionary societies in the South. The various northern freedmen’s aid and missionary societies and the Freedmen’s Bureau spent more than $31,000,000 on southern education from 1861 to 1893. This was nearly 30 per cent of the total amount expended for all Negro education in the South during those years. In 1888 of a total of 15,000 Negro teachers instructing more than 800,000 pupils in the South, 13,500 had been trained in schools supported by northern benevolence. The A.M.A. institutions alone had educated 7,000 teachers.38 The freedmen’s societies helped decrease the Negro illiteracy rate in the South from more than 90 per cent in 1861 to 81.1 per cent in 1870 and 70 per cent in 1880. Statistics do not tell the entire story of the contribution of freedmen’s associations. Their influence penetrated every southern state, awakening the freedmen to the need for education and proving that the Negro was capable of higher learning. The southern Negro colleges founded by these societies have helped to produce the present generation of Negro leaders who are gradually changing the pattern of race relations in the South. Truly the abolitionist impulse, which motivated the original freedman’s aid movement, has had a deep and lasting impact upon the southern Negro.

Abolitionist efforts to win suffrage and education for the freedmen were partially successful. The same cannot be said of their attempts to obtain land for the emancipated Negroes. After the war many abolitionists stepped up their agitation for the confiscation and redistribution of large plantations. “The nominal freedom of the slaves … must be actually secured by the possession of land,” wrote Edmund Quincy in April 1865. “If the monopoly of land be permitted to remain in the hands of the present rebel proprietors … the monopoly of labor might almost as well be given them, too.”39 Wendell Phillips, Anna Dickinson, Gerrit Smith, Lydia Maria Child, James Freeman Clarke, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, and many other abolitionists echoed these sentiments.

President Johnson’s amnesty proclamation of May 29, 1865, dealt a sharp blow to radicals who hoped for wholesale confiscation. The proclamation restored political and property rights to most rebels who would take an oath of allegiance. In subsequent months Johnson issued a large number of special pardons to men who had been exempted from the May 29 proclamation. Despite this setback, abolitionists continued to work for governmental action to secure land for the freedmen. They hoped for congressional reversal of Johnson’s policy of property restoration, just as they hoped for congressional reversal of the rest of his reconstruction program. Several radical Republican leaders agreed with the abolitionists on this question. “We must see that the freedmen are established on the soil, and that they may become proprietors,” wrote Charles Sumner. “From the beginning I have regarded confiscation only as ancillary to emancipation.” In his famous speech at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, on September 6, 1865, Thaddeus Stevens advocated confiscation of the property of large southern landholders and the grant of 40 acres to each adult freedman. But most Republicans shied away from the radicalism of wholesale confiscation. Prospects for the adoption of Stevens’ proposal or anything like it appeared dim in 1865.40

One of the anticipated functions of the Freedmen’s Bureau was resettlement of freedmen on abandoned and confiscated land. Johnson’s pardon and amnesty program, however, threatened to leave the Bureau with very little land for this purpose. In August 1865, Johnson issued a series of executive orders to General Howard instructing him to restore all confiscated property to former rebel owners except that which had already been sold under court decrees. These orders affected nearly all lands under Bureau control. The status of property along the South Atlantic coast assigned to the freedmen by Sherman’s Order no. 15 (see Chapter XI) became a burning issue during the winter of 1865-1866. More than 40,000 freedmen lived on 485,000 acres with the “possessory titles” granted by Sherman’s Order. In October 1865, Johnson sent General Howard to the sea islands to persuade the freedmen to return their farms to the pardoned owners. Howard had no taste for his mission, but like a good soldier he carried out his superior’s orders. He urged the freedmen quietly to abandon their farms and go back to work for their former masters.41

Freedmen on the sea islands could hardly believe their ears. “To turn us off from the land that the Government has allowed us to occupy, is nothing less than returning us to involuntary servitude,” said one of them. “They will make freedom a curse to us, for we have no home, no land, no oath, no vote, and consequently no country.”42 Some of the Negroes vowed to defend their farms by force if necessary. Abolitionists summoned all their eloquence to denounce the government’s action. “This villainous effort to rob loyal men for the benefit of ruffianly rebels whose hands are red with the blood of Northern soldiers, can succeed only through a breach of faith on the part of our government such as would be without parallel in history,” declared the Commonwealth. The Right Way asked: “Shall our own, and all coming ages, brand us for the treachery of sacrificing our faithful friends to our and their enemies? GOD IN HIS MERCY SAVE US FROM SUCH PERFIDY AND SUCH IDIOCY.” General Rufus Saxton, commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau in South Carolina, refused to carry out the order dispossessing the Negroes of their land, and Johnson removed Saxton from office on January 15, 1866. Even after Saxton’s removal the Freedmen’s Bureau moved slowly, hoping that Congress would enact legislation nullifying the president’s orders.43

In the end most of the freedmen were dispossessed. But the Freedmen’s Bureau bill passed over Johnson’s veto in July 1866, contained a provision for the lease of 20 acres of government-owned land on the sea islands to each dispossessed freedman with a six-year option to buy at $1.50 per acre. At the same time Congress passed the Southern Homestead Act, extending the principle of the homestead law of 1862 to the public lands of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi. The bill stipulated that until January 1, 1867, no one who had supported the Confederacy would be eligible for a homestead. This provision was intended to give the freedmen and Unionist whites first chance at the land. Abolitionists hoped for good results from the Southern Homestead Act, but their hopes were doomed to disappointment. Most of the lands opened for settlement were of inferior quality, and few freedmen had the necessary capital to buy tools and farm implements or to support themselves while they were trying to coax the first crop from the sandy soil. As a means of placing the freedmen on fertile land of their own, the Southern Homestead Act was a failure.44

Abolitionists soon discerned the inadequacy of the Homestead Act and renewed their demands for a program of confiscation and redistribution of southern plantations. An abolitionist traveler in the South reported in the fall of 1866 that the destitution of landless freedmen was appalling. He was alarmed by the nascent share-cropping and crop-lien systems that were taking root in the South. The Negroes “appear to have neither mind nor hope above their present condition, and will continue to work on from day to day, and from year to year, without more than enough to keep soul and body together,” wrote the traveler. “When addressing their masters, they take off their hats, and speak in a hesitating, trembling manner, as though they were in the presence of a Superior Being.” The freedman could never improve his status as long as he remained landless and penniless. “No other government ever ended a great rebellion before without confiscating the estates of principal rebels, and placing that mighty power, the landed interest, on its side.”45

In the spring of 1867 abolitionists stepped up their agitation for confiscation, hoping to win public support for such a policy before the next session of Congress. The Boston Commonwealth published a series of militant editorials, some of them by Elizur Wright, calling for expropriation. Wright chided “practical” Republican politicians who shrank from the radicalism of confiscation: “O ye mighty ‘practical’ men! don’t you know—are you not sensible—does it not ever enter your noddles to suspect—that if you have thirty thousand disloyal nabobs to own more than half the land of the South, they, and nobody else, will be the South? That they laugh, now in their sleeves, and by-and-bye will laugh out of their sleeves, at your schoolma’ams and ballot-boxes? They who own the real estate of a country control its vote.”46

At the annual meeting of the American Anti-Slavery Society in May 1867, Phillips introduced a resolution urging agrarian reform in the South as “an act of justice” to the Negro. Several speakers supported the resolution. Higginson said that confiscation “is an essential part of abolition. To give to these people only freedom, without the land, is to give them only the mockery of freedom which the English or the Irish peasant has.” Without land the Negro voter would be at the mercy of the planter, who could use economic coercion to dictate his vote. “The time will come,” said Higginson, “when the nation must recognize that even political power does not confer safety upon a race of landless men.” Phillips’ resolution was adopted almost unanimously by the Society.47 The New England Anti-Slavery Society passed a similar resolution three weeks later. In the following months Phillips hammered away relentlessly at the confiscation theme. “What we want to give the negro is what the masses must have or they are practically serfs, the world over,” he declared. Confiscation during the French Revolution crippled the aristocracy; confiscation uprooted Toryism in the American Revolution. “Land is the usual basis of government,” said Phillips; “the class that hold it must, in the long run, give tone and character to the Administration. It is manifestly suicidal, therefore, to leave it in the hands of the hostile party.”48

But abolitionists were fighting a losing battle on the confiscation front. A majority of the Republican party was opposed to the measure. The New York Times thought that “the colored race is likely to be injured, rather than aided, by this sycophantic and extravagant crusade on its behalf.” The Times urged friends of the freedmen to teach the lessons of labor, patience, frugality, and virtue to the Negro rather than demand special favors for him. Horace Greeley thought the agitation for confiscation was “either knavery or madness. People who want farms work for them. The only class we know that takes other people’s property because they want it is largely represented in Sing Sing.”49 The Democratic gains in the 1867 elections put a virtual end to the drive for confiscation. The mood of radicalism which might have sustained confiscation in 1866 or 1867 had passed away. There was no longer any chance (if indeed there ever had been) that Congress would pass a confiscation bill or any other wholesale measure to provide farms for the freedmen.

In 1869 abolitionists set forth a new plan to obtain land for the freedmen. Aaron M. Powell, editor of the Anti-Slavery Standard, drew up a petition urging Congress to create a federal land commission, to be composed of “well-known, disinterested friends of the freed people.” The commission would be capitalized at $2,000,000 by the U.S. Treasury and empowered to buy up large tracts of available southern land for resale in small lots to the freedmen at low cost and on easy terms. The commission would also be authorized to make loans to the freedmen for transportation, tools, implements, building materials, and seed. Abolitionists circulated the petition widely in 1869-1870, obtaining thousands of signatures from southern freedmen as well as their northern sympathizers. A Tennessee congressman introduced a bill to create such a land commission, but it died in committee, the last monument to Congress’s failure to place the freedmen in a position of economic viability.50

Abolitionists backed several private schemes to settle the freedmen on farms of their own. In 1865 a group of Boston and New York capitalists incorporated the “American Land Company and Agency,” with Governor John Andrew as president. George L. Stearns was one of the largest stockholders in this company, whose purpose was to channel northern investment into the South to help rebuild the section’s economy and settle as many freedmen as possible on land of their own. Andrew and Stearns reasoned that the war had left southern planters poor in everything except land. They planned to buy part of this land in order to provide the planters with enough capital to farm the remainder. The company could then resell some of its purchased property to the freedmen. Things went badly from the beginning, however. The company invested heavily in Tennessee cotton plantations, but crop failures in 1866 ate up most of the capital. Stearns’ death in the spring of 1867 brought the enterprise to bankruptcy and failure.51

Not all of the private efforts to provide freedmen with land were failures. In 1865 John G. Fee, a Kentucky-born abolitionist and cofounder of Berea College, purchased 130 acres in central Kentucky and resold the land in small tracts to freedmen, who established a village on the property. In 1891 there were 42 families living in this village. Fee urged the American Missionary Association to go into the business of selling land to the freedmen. In 1868 the A.M.A. began purchasing plantations for resale to Negroes. On each tract of land the A.M.A. established a church and school, and several small agricultural villages grew up in the South around these A.M.A. centers. The A.F.U.C. also had a small fund for the purchase and resale of farms to the freedmen. In 1869 a group of Boston abolitionists and philanthropists purchased a plantation in Georgia and started a “Southern Industrial School and Labor Enterprise.” William and Ellen Craft, a couple who had escaped from slavery before the war, went to Georgia to manage the enterprise. They were accompanied by Yankee farmers who taught the freedmen the latest methods of planting, seeding, plowing, and so on. The freedmen attended the vocational and agricultural school part of the day and worked in the fields the rest of the time. They were encouraged to save their wages to buy land for themselves. The Ku Klux Klan burned the crop and buildings of the plantation in 1871, but the Crafts rebuilt the school and carried on in Georgia until 1878, when they sold the plantation in small tracts to the freedmen and returned to Boston.52

One of the most ambitious abolitionist efforts to secure land for the freedmen by private investment was a plan developed by Charles Stearns, an old-line Garrisonian from Springfield, Massachusetts. In 1854 Stearns had gone to Kansas to fight for freedom, and in 1860 he drifted west to Colorado Territory. He went to Georgia in May 1866, and purchased a 1,500-acre plantation near Augusta. He hoped to run the plantation for a few years on the cooperative principle and then sell it in small tracts to the freedmen who had worked for him.53

Stearns was filled with enthusiasm for his project when he first came South. He established night and Sunday schools to teach his laborers to read and write. Southern neighbors told him that he could never “manage the niggers” with kindness, but would be compelled to use force and punishment if he wanted to get any work out of them. Stearns hoped to prove his neighbors wrong. He substituted kindness, incentive bonuses, and moral suasion for insults and punishment. In a summary of his experiences written several lears later, Stearns admitted that the practical realities of the situation had soon modified his enthusiasm. The freedmen were inefficient workers and destroyed tools and implements by their carelessness. Stearns almost succumbed to disillusionment and despair several times. But he always rallied himself with the thought that slavery was a poor school for efficiency, honesty, or skill, and returned to work with renewed dedication. He later evaluated his experiment as a success. After six years the Negroes on his plantation were better educated, more honest, and more industrious than when he first came.54

Inability to pay off the mortgage on his plantation forced Stearns to postpone his plans to sell the land to his employees. In 1869 his creditors threatened to foreclose, and Stearns hurried to Boston to raise $6,000 to pay the mortgage. Samuel Sewall and Wendell Phillips listened sympathetically to Stearns’ proposition. Sewall gave him a $1,000 loan, and Phillips and Sewall helped him raise the remaining $5,000. He returned to Georgia and inaugurated his plan to sell the plantation in 25-acre lots to the Negroes. Only 20 freedmen were able to buy during the first year, and some of them soon fell behind on their payments. By the end of 1870 Stearns was in debt again and about ready to give up in despair. “I am certain I can never cultivate a farm successfully with the blacks as laborers,” he wrote in his diary. “Nothing can be done without incessant and minute supervision of them, such as I am not able to give.” He almost sold the plantation to one of his white neighbors, but his mother, who had come South to teach the freedmen, convinced him that to do so would be a breach of faith with the Negroes he had worked so hard to help. Stearns heeded her pleas. He stayed on for another year and began writing a book about his experiences in an effort to promote northern interest in the needs of the freedmen.55

In 1872 Stearns brought a group of 50 Massachusetts farmers and missionaries to his plantation to establish an agricultural and industrial colony. The Yankee farmers soon transformed the establishment into a model of efficiency and neatness. Most of the Negroes stayed on the plantation and tried to learn better methods of farming from the Yankees. Stearns returned to Boston to finish his book and to set on foot a project for northern purchase and resale of southern plantations to freedmen. In 1873 he organized a “Laborers’ Homestead and Southern Emigration Society” with a planned capitalization of $50,000. Samuel Gridley Howe served as president, and Stearns, Phillips, and James Buffum (an abolitionist) acted as a three-man board of trustees. The Society purchased some property in Virginia to start their experiment. Stearns sent out hundreds of circulars urging capitalists to invest in his Society. Lands purchased by the trustees would be resold in 25-acre tracts on easy terms to freedmen and northern settlers. The Society planned also to make loans to the purchasers to enable them to buy tools, seed, and implements. Stearns had grandiose plans for his Society. He urged Congress to lend it $1,000,000 per year for ten years. Congress took no note of his appeal, however, and the panic of 1873 soon dried up Stearns’ meager sources of private capital. Apart from the Georgia plantation and the property in Virginia he had little to show for his efforts. He had established one agricultural colony and sold land to several dozen freedmen. It was a rather small ending to an ambitious beginning.56

In 1880 Frederick Douglass attributed the failure of Reconstruction to the refusal of Congress to provide the freedmen with an opportunity to obtain good land of their own. “Could the nation have been induced to listen to those stalwart Republicans, Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner, some of the evils which we now suffer would have been averted,” declared Douglass. “The negro would not today be on his knees, as he is, supplicating the old master class to give him leave to toil…. He would not now be swindled out of his hard earnings by money orders for wages with no money in them.”57 Many abolitionists still alive in 1880 would have agreed with Douglass. They had done their best to call attention to the necessity of land for the freedmen, but the nation was not sympathetic enough toward the plight of the Negro to provide any adequate means by which he could obtain land. As a result the Negroes remained economically a subordinate class, dependent upon white landowners or employers for their livelihood. The South was not “reconstructed” economically, and consequently the other measures of reconstruction rested upon an unstable foundation.

1 Liberator, Dec. 30, 1864; N.A.S. Standard, Jan. 7, 1865.

2 American Missionary, VIII (June 1864), 150.

3 Rupert S. Holland, ed., Letters and Diary of Laura M. Towne, Written from the Sea Islands of South Carolina, 1862-84 (Cambridge, Mass., 1912), xvi-xvii and passim; John White Chadwick, Sallie Holley, A Life for Liberty (New York, 1899); Caroline Putnam to William L. Garrison, Jr., May 23, 1907, Garrison Papers, sc. See also Henry Lee Swint, The Northern Teacher in the South, 1862-1870 (Nashville, 1941), 35-56. The private correspondence of leading abolitionists, the antislavery newspapers, and the monthly journals of the various freedmen’s aid societies contain uncounted hundreds of letters from abolitionists who had gone South to teach the freedmen.

4 Swint, Northern Teacher, 26-32, 51n., 143-74; for McKim’s activities, see his letterbooks as corresponding secretary of the American Freedmen’s Aid Commission and the American Freedmen’s Union, Commission in the McKim Papers, Cornell; for the personnel of the A.M.A., see Richard B. Drake, “The American Missionary Association and the Southern Negro, 1861-1888,” Ph.D. dissertation, Emory University, 1957, 78-98; Levi Coffin, Reminiscences (Cincinnati, 1880), 651-712; Charles Kassel, “Edwin Miller Wheelock,” Open Court, XXXIV (Sept. 1920), 569.

5 G. B. Emerson, S. May, Jr., and T. J. Mumford, Memoir of Samuel Joseph May (New York, 1871), 229-30; Samuel J. May to J. Miller McKim, Jan. 28, 31, Feb. 1, 16, May 13, July 9, 20, 26, Aug. 15, 1866, July 18, Oct. 21, 1867, McKim Papers, Cornell; L. M. Child to James T. Fields, Aug. 23, 28, Sept. 3, 1865, Child Papers, Radcliffe Women’s Archives; L. M. Child to Lewis Tappan, Jan. 1, 30, 1869, Tappan Papers, LC; John G. Fee, Autobiography (Chicago, 1891), 173-80; Joseph W. Parker, “Memoirs,” typescript of MS supplied by Mrs. Perce J. Bentley, 106-10, 121-22, 128-34, 143-46; William H. Daniels, Memorials of Gilbert Haven (Boston, 1880), 183-84, 202-05. The Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery, founded in 1775 by antislavery Quakers of Philadelphia, contributed money to 61 schools and colleges for the freedmen during Reconstruction. Centennial Anniversary of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery … April 14, 1875 (Philadelphia, 1875), 40.

6 Freedmen’s Record, I (April 1865), 61-64 (May 1865), 73 (July 1865), 110-11, 120; Commonwealth, Apr. 15, July 1, 1865; N.A.S. Standard, July 22, 29, 1865; Liberator, July 21, 1865; Luther P. Jackson, “The Educational Efforts of the Freedmen’s Bureau and Freedmen’s Aid Societies in South Carolina, 1862-1872,” Journal of Negro History, VIII (Jan. 1923), 19-20; Alrutheus A. Taylor, The Negro in South Carolina during Reconstruction (Washington, 1924), 85-86. With the opening of the fall term in 1865 the public school system in Charleston again came under the control of native white officials, who assigned all Negro children to the Morris Street School, where they were taught by southern whites. One of the best Negro schools in the city, however, was the Shaw Memorial Institute, named in honor of Colonel Robert Shaw, and sustained primarily by the Shaw family and their abolitionist friends until 1874, when it was incorporated into the public school system of the city. Taylor, The Negro in South Carolina Reconstruction, 86-89.

7 E. C. Stanton et al., History of Woman Suffrage (6 vols., New York, 1881-1922), II 28-33; Josephine Griffing to Sumner, Nov. ?, 1864, Sumner Papers, HU; Memo. of Governor Buckingham of Connecticut, in Griffing Papers, CU; N.A.S. Standard, Sept. 1, 1866.

8 George Bentley, A History of the Freedmen’s Bureau (Phila., 1955), 77-78; Stanton et al., History of Woman Suffrage, II, 29, 33; Mrs. Griffing to E. B. Chace, Dec. 26, 1865, in Lillie B. C. Wyman and Arthur C. Wyman, Elizabeth Buffum Chace (2 vols., Boston, 1914), I, 285-86; Levi Coffin to McKim, Jan. 2, 1866, McKim to Coffin, Jan. 6, 1866, McKim Papers, Cornell; Freedmen’s Record, I (Feb. 1865), 17-18; N.A.S. Standard, Jan. 27, 1866.

9 Mrs. Griffing to Sumner, Feb. 12, 1867, Mar. 30, Apr. 10, 1869, Sumner Papers, HU; Mrs. Griffing to Gerrit Smith, Aug. 5, 12, 1869, Aug. 26, 1870, Mar. 13, 1871, Catharine Stebbins to Gerrit Smith, Aug. 17, 1870, Smith Papers, SU; Sumner to Mrs. Griffing, Apr. 2, 1868, July 27, Dec. 7, 1869, Mrs. Griffing to Lucretia Mott, Apr. 22, 1870, Griffing Papers, CU; New York World, Feb. 25, 1870; National Standard, Apr. 1, 1871.

10 Horace Greeley to Griffing, Sept. 7, 1870, Griffing to Greeley, Sept. 12, 1870, Wade to Griffing, Nov. 12, 1869, Griffing Papers, CU.

11 Quoted in Swint, Northern Teacher, 27.

12 McKim to Arthur Albright, Oct. 19, 1866, McKim Papers, BPL; McKim to S. P. Chase, Oct. 15, 1866, Chase Papers, LC.

13 Freedmen’s Journal, I (Jan. 1865), 3.

14 Bentley, Freedmen’s Bureau, 172-76; Luther Jackson, “The Educational Efforts of the Freedmen’s Bureau and Freedmen’s Aid Societies in South Carolina,” op.cit., 13-15; McKim to Joseph Simpson, Feb. 28, 1866, McKim letterbooks, I, 400, McKim Papers, Cornell; McKim to Arthur Albright, Mar. 23, 1866, McKim Papers, BPL; Drake, “American Missionary Association,” 37-43.

15 The story of the merger of the secular freedmen’s aid societies can be traced in the correspondence of J. Miller McKim in his papers at Cornell; Julius H. Parmelee, “Freedmen’s Aid Societies, 1861-1871,” Negro Education: A Study of the Private and Higher Schools for Colored People in the United States, U.S. Dept. of Interior; Bureau of Education Bulletin, 1916, no. 38, pp. 269-71, 275, 289; and American Freedman, I (May 1866), 25-31 (Sept. 1866), 82 (Oct. 1866), 99.

16 The statements in this paragraph are based upon a reading of hundreds of letters from teachers printed in the American Freedman and Freedmen’s Record from 1865 to 1869.

17 Paducah Herald, quoted in Right Way, June 23, 1866.

18 Freedmen’s Record, III (Apr. 1867), 54. For a general discussion of the tensions between northern teachers and southern whites, see Swint, Northern Teacher, 77-142.

19 Arthur Albright to McKim, Feb. 16, 1866, McKim to Albright, Mar. 6, 1866, McKim letterbook, I, 445-49, McKim Papers, Cornell.

20 N.A.S. Standard, May 6, 1865; Liberator, May 26, 1865; Douglass to McKim, May 2, 1865, McKim Papers, Cornell.

21 McKim to Richard Webb, Mar. 27, 1865, Garrison Papers, BPL.

22 Ira Brown, “Lyman Abbot and Freedmen’s Aid, 1865-1869,” Journal of Southern History, XV (Feb. 1949), 23-28.

23 McKim to E. H. Irish, Feb. 8, 1866; McKim to Wm. H. Furness, Mar. 30, 1866; Samuel May, Jr., to McKim, Feb. 20, Mar. 5, 1866; Garrison to McKim, Mar. 31, 1866; McKim to F. J. Child, Dec. 9, 1865, McKim to Joseph Simpson, Feb. 16, 1866, McKim to Laura Towne, Feb. 21, Apr. 4, 1866, McKim to Reuben Tomlinson, Apr. 4, 1866, McKim letterbooks, I, 170-71, 328-29, 381, 458-60, 535-36, McKim Papers, Cornell; American Freedman, I (May 1866), 19-20.

24 American Freedman, I (April 1866), 2-3, 5-6.

25 Freedmen’s Record, II (Mar. 1866), 37-38.

26 Elizabeth Botume, First Days Amongst the Contrabands (Boston, 1893), 257-58; Freedmen’s Record, III (Oct. 1867), 154.

27 N.A.S. Standard, May 12, 19, 1866. For several letters from abolitionists praising the stand of the freedmen’s societies on school integration, see American Freedman, I (May 1866), 23-24.

28 The Garrison Papers and the Samuel May, Jr., Papers, BPL, contain a great deal of correspondence relating to this issue. See also N.A.S. Standard, July 20, Aug. 10, 24, 1867, Feb. 15, Mar. 14, June 13, 1868. Garrison and Phillips effected a personal reconciliation in the early 1870’s, and the bitterness between other abolitionists gradually dissolved during the decade.

29 The dispute between the secular and evangelical societies can be traced in American Missionary, X (Sept. 1866), 193-94 (Oct. 1866), 226-28, XI (Sept. 1867), 205; Freedmen’s Record, III (Jan. 1867), 1-2; American Freedman, I (Dec. 1866), 130-31 (Jan. 1867), 146-47, II (April 1867), 194; Lewis Tappan to J. Sella Martin, July 3, 1865, Tappan to Levi Coffin, Jan. 30, 1865, Tappan letterbook, Tappan Papers, LC; McKim to Garrison, Mar. 29, 1866, McKim to Arthur Albright, Mar. 15, 1867, McKim to J. W. Alvord, Jan. 23, 1868, McKim Papers, Cornell; Swint, Northern Teacher, 37-40; and Drake, “American Missionary Association,” 18-26.

30 Drake, “American Missionary Association,” 37-75; O. O. Howard to McKim, June 6, 1867, Samuel May, Jr., to McKim, July 22, 1870, McKim Papers, Cornell.

31 American Freedman, I (Jan. 1867), 147, II (April 1867), 196; Parmelee, “Freedmen’s Aid Societies,” op.cit., 275.

32 E. S. Philbrick to Wm. C. Gannett, Oct. 15, 1865, in Elizabeth Pearson, ed., Letters from Port Royal (Boston, 1906), 317-18; American Freedman, II (Apr. 1867), 195. See also Freedmen’s Record, II (Sept. 1866), 157-59, III (April 1867), 52 (May 1867), 69, IV (April 1868), 51; and Reuben Tomlinson to McKim, Sept. 24, 1866, McKim Papers, Cornell.

33 Parmelee, “Freedmen’s Aid Societies,” op.cit., 271-75, 292-96; Drake, “American Missionary Association,” 275-76; McKim to Garrison, Dec. 2, 15, 1867, Feb. 1, 1868, Gerrit Smith to J. Miller McKim, Nov. 1, 1868, S. P. Chase to McKim, Nov. 6, 1868, Garrison Papers, BPL; McKim to Gerrit Smith, Nov. 6, 18, 1868, Smith Papers, SU; Freedmen’s Record, IV (July 1868), 106-08 (Nov. 1868), 169; American Freedman, III (April 1869), 1-2.

34 Freedmen’s Record, IV (Oct. 1868), 155-56; American Freedman, III (April 1869), 2.

35 Alrutheus A. Taylor, The Negro in Tennessee, 1865-1880 (Washington, 1941), 182; National Standard, I (July 1870), 146-51.

36 National Standard, Oct. 22, Nov. 19, Dec. 17, 1870, Jan. 7, Feb. 11, Mar. 11, Apr. 15, Oct. 28, 1871; George F. Hoar, Autobiography of Seventy Years (2 vols., New York, 1903), I, 265.

37 Freedmen’s Record, III (Jan. 1867), 2 (Oct. 1867), 143, IV (April 1868), 50-51; Augustus F. Beard, Crusade of Brotherhood, A History of the American Missionary Association (Boston, 1909), 100-04, 147-89; Drake, “American Missionary Association,” 159-85.

38 Harriet Beecher Stowe, “The Education of Freedmen,” North American Review, CXXVIII (June 1879), 605-15, and CXXIX (July 1879), 81-94; Drake, “American Missionary Association,” 185-205.

39 N.A.S. Standard, Apr. 1, 1865.

40 Sumner to John Bright, Mar. 13, 1865, in Edward L. Pierce, Memoir and Letters of Charles Sumner (4 vols., Boston, 1877-94), IV, 229; Fawn M. Brodie, Thaddeus Stevens: Scourge of the South (New York, 1959), 231-33. See also Commonwealth, June 10, 17, 1865; Independent, June 22, 1865; Liberator, June 23, Aug. 11, 1865; N.A.S. Standard, May 26, 1866; New York Tribune, Apr. 11, Sept. 11, 12, 1865.

41 Bentley, Freedmen’s Bureau, 87-98; Edwin D. Hoffman, “From Slavery to Self-Reliance,” Journal of Negro History, XLI (January 1956), 20-24; N.A.S. Standard, Oct. 7, 1865.

42 Quoted in N.A.S. Standard, Oct. 7, 1865.

43 Commonwealth, Nov. 4, 1865; Right Way, Dec. 80, 1865; Bentley, Freedmen’s Bureau, 98-101. See also Liberator, Nov. 17, Dec. 1, 15, 22, 1865; Independent, Dec. 7, 1865.

44 Bentley, Freedmen’s Bureau, 134, 144-46; Patrick W. Riddleberger, “George W. Julian: Abolitionist Land Reformer,” Agricultural History, V (July 1955), 110; Independent, July 5, 1866; Commonwealth, July 14, 1866; Right Way, July 14, 1866; N.A.S. Standard, Dec. 18, 1869. See also Paul W. Gates, “Federal Land Policy in the South, 1866-1888,” Journal of Southern History, VI (Aug. 1940), 304-10.

45 Article by the Rev. John Savary in N.A.S. Standard, Nov. 3, 1866.

46 Commonwealth, Mar. 23, 1867. See also ibid., Mar. 30, Apr. 6, 1867.

47 N.A.S. Standard, May 18, 25, 1867.

48 ibid., June 8, 15, 1867.

49 New York Times, June 1, Oct. 26, 1867; New York Tribune, June 20, 1867.

50 N.A.S. Standard, Dec. 18, 25, 1869, Jan. 29, Feb. 5, 12, 26, Mar. 12, 1870.

51 Henry G. Pearson, The Life of John A. Andrew (2 vols., Boston, 1904), II, 267-69; Frank P. Stearns, The Life and Public Services of George Luther Stearns (Phila., 1907), 352.

52 John G. Fee, Autobiography (Chicago, 1891), 182-83; Drake, “American Missionary Association,” 115-19; McKim to O. O. Howard, Nov. 27, 1866, Howard to McKim, Dec. 1, 1866, McKim Papers, Cornell; N.A.S. Standard, Nov. 6, 20, 1869; L. M. Child to Elisa Scudder, Feb. 6, 1870, Child to Lucy Osgood, Feb. 14, 1870, Child Papers, Cornell; Commonwealth, Aug. 16, 1873; Garrison to Fanny Garrison Villard, June 14, 1878, Garrison Papers, BPL.

53 Charles Stearns to Garrison, Jan. 21, 1863, in Liberator, Mar. 20, 1863; Stearns to Garrison, Mar. 27, 1865, in Liberator, Apr. 21, 1865; Charles Stearns, The Black Man of the South, and the Rebels (New York, 1872), 20-39.

54 ibid., 28, 49-54, 59-71, 115-16, 164, and passim.

55 Stearns to Gerrit Smith, June 26, 1869, Smith Papers, SU; Commonwealth, July 24, 1869; N.A.S. Standard, Sept. 25, Nov. 20, 1869; Stearns, The Black Man of the South, 154-55, 170, 258-75, 278-819; quotation from ibid., p. 279.

56 ibid., 319-25, 512-42; Stearns to Gerrit Smith, Feb. 17, 1873, Feb. 4, 11, 1874, Smith Papers, SU; Commonwealth, June 27, Sept. 19, 1874; Stearns to Garrison, Dec. 12, 1876, Garrison Papers, BPL.

57 Speech of Douglass at Elmira, New York, Aug. 1, 1880, copy in Douglass Papers, Anacostia.