The Iberian Peninsula occupies several crucial crossroads, providing connections between Europe and Africa, the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, and Europe and the Atlantic world. Spain's connections with Africa date from prehistoric times. When Muslim rulers controlled most of Spain during the Middle Ages, the close relationship with the North African world intensified. Today, Spain is the destination of choice for African would-be immigrants to Europe. Spain's connections with the rest of Europe are powerful as well, defined by history and geography and enhanced by the ties of the European Union. Spain's connections with Latin America date from the period of exploration and empire-building in the late fifteenth century. In our times, Spain provides an important link between Europe and Latin America, with the greatest number of flights between the two continents, the largest investment in Latin America of any European country, and the most Latin American immigrants in Europe. For the world as a whole, Spain is a major center of tourism. In 2007 Spain ranked second in the world in the number of tourists, according to the World Tourism Organization. In that year, some 59.2 million tourists entered the country, compared to a Spanish population of about 45 million, a clear indication of Spain's continuing importance as a nexus of travel, transportation, and exchange.

This is a concise history of Spain, which we understand to mean a modern country that shares the Iberian Peninsula with Portugal. All of those geographical terms have a complex history, however. The Greeks called the whole peninsula “Iberia,” and the Romans called it “Hispania.” Between the end of the Roman Empire and the eighteenth century, “Spain” was more a term of convenience than a political reality, and other terms have come and gone to describe the land and its peoples. When the Muslims held Spain, they called the part they controlled “al-Andalus,” an area that varied in geographical extent as the area under Islamic control waxed and ultimately waned. Medieval Jews called the country “Sefarad.” Christian Spain in the Middle Ages contained a number of kingdoms and smaller entities. Castile and Aragon were the most prominent of those kingdoms and, by the end of the Middle Ages, controlled a large portion of the peninsula. The marriage of their rulers Isabel of Castile and Fernando of Aragon marked the origin of the modern definition of Spain. Since the eighteenth century, the political geography of Spain has remained more or less constant: the Iberian Peninsula with the exception of Portugal, Andorra, and Gibraltar. In modern times, most writers employ the Greek word “Iberia” to refer to the peninsula and a descendant of the Roman word “Hispania” to refer to Spain. In other words, Spain and Iberia are not equivalent, although they were both equivalent and coterminous in Greek and Roman times, referring to the peninsula as a whole.

That Portugal developed as an independent kingdom was also a product of history and happenstance. In the later Middle Ages, the western part of the peninsula was developed mainly by conquerors and settlers from Galicia in the northwest, whose overlord was the king of León. In the twelfth century, Afonso Henriques, count of Portugal, worked to secure papal recognition of Portugal's independence and of his status as its king. Nonetheless, Portugal could have been joined with Spain on several occasions. A Castilian invasion failed in the fourteenth century. Isabel and Fernando in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries secured marriage alliances with the Portuguese ruling house that could have led to a unified peninsula, but the deaths among the marriage partners ended that effort. Felipe II of Spain secured the Portuguese throne in 1580, and Spain and Portugal had the same Habsburg rulers until 1640. In that year, a revolt began that eventually restored Portuguese independence and enshrined resistance to Spain as a part of Portugal's national identity. In short, Spain has rarely been identical to Iberia and, for most of its long history, Spain itself was a theoretical concept or a term of convenience overlaid on a patchwork of kingdoms and regions with shifting boundaries. In the present day, leaders of regional political movements contest the notion of Spain as an indivisible entity, instead looking back to ancient and medieval antecedents for their modern self-definition.

As part of this regional complexity, Iberia has always been multiethnic, multireligious, and multicultural. One way to trace modern regionalism is to examine the peninsula's different languages, both historic and current. Most of the languages of the peninsula are so-called “Romance” languages derived from Latin, a legacy of the centuries-long Roman occupation and control of Hispania. The language spoken by the greatest number of present-day Iberians and Spanish-speakers throughout the world is Castilian, the descendant of the language of medieval Castile. Most non-Spaniards call this language “Spanish.” It was exported to the Spanish Empire in the Americas and the Philippines, and is the language with the third-highest number of speakers in the world today, following Chinese and English. The regime of Francisco Franco in the mid twentieth century tried to make Spanish or Castilian the only language of Spain, but linguistic identity persevered and provided a strong component of regional struggles for increased recognition and autonomy during the regime.

Among the other Romance languages in the peninsula, Portuguese is the official language of Portugal, and its close cousin Gallego, the language of Galicia, is seeing a revival in northwestern Spain, spoken and written on local radio and television stations and in the publishing industry. The Catalan language is prominent in education and the media as the mother tongue of many residents of Catalonia. Catalan is intimately related to the medieval language of the south of France, the langue d'oc or Occitan. In medieval times, Catalans took their language to Valencia and the Balearic Islands in the course of conquering those areas. Today the languages in those regions are somewhat different from but closely related to Catalan.

Aside from the Romance languages, other languages have also figured prominently in Spanish history. The most unusual is the Basque language, Euskerra, one of Europe's oldest spoken languages, going back to prehistoric times. With the language in decline by the nineteenth century, Basque intellectuals revived its use and developed a written form, which it had formerly lacked. Since then, the use of Euskerra has been associated with Basque nationalism and the quest for various degrees of autonomy from the Spanish government. The most extreme element of the nationalist movement, known as ETA, from the Basque phrase “Homeland and Freedom,” aims at total independence from Spain and has waged a campaign of terrorism and extortion since 1968.

The Arabic language came to Iberia with the Islamic conquerors in the eighth century and remained the language of the political elite of al-Andalus. In parts of Spain, Arabic remained current into the seventeenth century. It strongly influenced Castilian and the other Romance languages in the peninsula and eventually contributed variants of nouns from “algebra” to “zenith” to languages throughout Europe. Arabic is coming back into Spain with the immigration of Muslims from North Africa and elsewhere in the Islamic world, and with the contemporary conversion of some native Spaniards to Islam and their exposure to the language of the Qur’ān.

For centuries, Hebrew was the common language of the flourishing Jewish communities of medieval Spain. It influenced and was influenced by both Arabic and the Romance languages. Largely extirpated or driven underground by the expulsion of the Jews at the end of the fifteenth century, Hebrew has returned to Spain from the mid twentieth century onward with the establishment of communities of Jews from Morocco and other parts of North Africa and the Middle East.

The various historical languages of Iberia serve as a potent reminder of other facets of regional difference. Underlying everything is the geology of the peninsula, comprising a diverse series of zones from glaciers in the high northern mountains to a small area of true desert in the southeast near Elche. Iberia's mountain ranges, which were formed millions of years ago, separate and define Spain's distinctive regions. In the northeast, the Pyrenees divide Spain from France with peaks that reach to over 11,000 feet. The valleys and low mountains of the Basque country connect the Pyrenees with the Cantabrian Mountains (Cordillera Cantábrica), with a maximum height of some 8,500 feet, which stretch across most of the rest of northern Spain, separating a narrow coastal strip of land from the interior of the peninsula. At the western end of the Cantabrian range is Asturias, with its daunting coastal cliffs and mountainous interior. The coastal mountains and valleys of Galicia in the extreme northwest of Spain are similar to those of Asturias. Galicia's coastline is dominated by rías, fingers of the Atlantic Ocean probing into the interior between hills, similar to the fiords of Scandinavia, though less dramatic.

South of the western edge of the Cantabrian ranges, the mountains of León slope southward onto a huge plateau called the Northern Meseta, with an average altitude of 2,300 to 2,600 feet. To the east it is bounded by the Iberian Mountains (Cordillera Ibérica), with peaks as high as 7,500 feet. Farther eastward lie the Ebro River valley in Aragon and Catalonia and the rich plains of Valencia near the Mediterranean coast. The southern edge of the Northern Meseta meets the Central Mountains (Cordillera Central), a mountain chain north and west of Madrid whose ranges include the Somosierra, Guadarrama, and Gredos.

Farther south, the Southern Meseta has an average altitude of 2,000 to 2,300 feet. The high plains of the two Mesetas, comprising about 36 percent of the Iberian Peninsula, are isolated from one another. They are high enough and large enough to give Spain a mean altitude of nearly 2,200 feet, second only to Switzerland in Europe and double the European average. Over 56 percent of the surface area of Spain lies between 1,300 and 3,300 feet. In many places, a traveler can descend from the high plains into impressive mountain ranges before reaching plains at lower altitudes. Madrid, in the center of the country, has the highest elevation of any European capital, with its airport almost exactly 2,000 feet above sea level.

The Southern Meseta's eastern edge lies between the mountains of the Cordillera Ibérica (which also borders the Northern Meseta) and the even more daunting Baetic Mountains (Cordillera Bética), which separate the southeastern desert and coastal plain from the Southern Meseta. The Sierra Morena mountain range marks the southern border of the Southern Meseta. South and west of the Sierra Morena, the Guadalquivir River valley, a broad and rich agricultural plain, slopes southwestward toward the Atlantic Ocean. Farther east, the Sierra Nevada Mountains, south of Granada and the other southern ranges, rise to peaks ranging from 3,300 to 11,500 feet. As their name implies, the mountain-tops of the Sierra Nevada are snow-capped all year, providing a stunning contrast with the hot plains and coastal areas in the rest of Andalusia.

Over the centuries, the difficult topography of Spain has limited agriculture and hampered long-distance transport, separating seaports from inland plains and cities and hindering commercial development. Before the advent of the railroads, topography put a premium on goods that could be easily moved, or better yet that could move themselves, such as livestock.

Physical Iberia, showing major cities, rivers, and mountain ranges.

The rivers of the peninsula provide little opportunity for transport by boat or barge. They tend to make short, rapid descents from their origins in the mountains, and most suffer from variations in flow according to erratic and unpredictable rainfall. Many Spanish rivers, even those with considerable volume, flow through steep banks that make them very difficult to use as sources for irrigation.

Despite these limitations, before the nineteenth century Spanish rivers carried considerable boat traffic along their navigable stretches. In modern times, roads and railroads supplanted the rivers as thoroughfares, with the exception of the lower reaches of the largest rivers. Nonetheless, the major rivers of Spain help to define the regions through which they flow and have been the scenes of important historical developments. One historian has even suggested that we might best understand the medieval history of Spain by tracing the changes in political control of the major river valleys.

Only one of the largest Spanish rivers flows into the Mediterranean: the Ebro, rising in the Cantabrian Mountains, flowing through the valleys of Aragon, and reaching the sea 565 miles from its source, after traversing the delta it created. In Roman times the river had a significant seaport at Amposta, then located on the Mediterranean coast and now located, due to silting and the formation of the delta, about 16 miles from the sea. Historically, the Ebro formed the spine of a series of routes into the center of the peninsula. The city of Zaragoza has been, since its Roman foundation, the principal inland crossing point of the Ebro, a fact that assured the city's prominence.

The northernmost of the major rivers that flow into the Atlantic is the Duero, rising in the Sierra de Urbión and flowing through the grain- and wine-producing regions of Old Castile and northern Portugal. The Duero and its valley formed a frontier zone between al-Andalus and the Christian kingdoms in medieval times, as Christian forces began to wrest control of the peninsula from the Muslims. In the eighteenth century, the Duero and some of its tributaries in Old Castile served as the nexus of a major effort at canal-building. The canals still remain but fell into disuse when the railroads came in the nineteenth century. The Duero is navigable for only a short distance before it reaches the Atlantic at the Portuguese city of Porto. The lower Duero (Portuguese Douro) today supports a system of barge carriers for wine and other goods.

Farther south is the Tajo River (“Tagus” in English), rising in the Sierra de Albarracín and flowing around the tall hill that defines Toledo, a military strongpoint since its founding by the Romans. Its conquest from the Muslims in 1085 by Alfonso VI of Castile marked an important step in the Castilian move into central Iberia. A favored residence of medieval kings, Toledo housed an important Jewish community whose synagogues still stand as a tourist destination. During the Spanish Civil War, Toledo was the scene of a famous siege, an event more important for propagandistic than strategic reasons. From central Spain, the Tajo flows into Portugal, where it is called the Tejo, and farther on forms the great estuary upon which Lisbon is located.

Still farther south, the Guadiana (Arabic “Wadi Ana”) rises in the province of Cuenca and flows through La Mancha and southern Extremadura. These historically underpopulated areas were the location of winter pastures for Spain's famous Merino sheep, the vast migratory flocks that produced the finest of wools from the thirteenth century onward. In ancient and medieval times, there was considerable boat transport on the navigable stretches of the Guadiana, centering on Mérida and then on the lower reaches south of the waterfall at Pulo do Lobo in Portugal. As the Guadiana passes through Extremadura, four large dams form the main links of a project of the 1950s and 1960s to provide electric power and water for irrigation in a broad area around the city of Badajoz. After defining part of the border between Spain and southeastern Portugal, and providing a navigable stretch of some 43 miles, the Guadiana reaches the Atlantic between Ayamonte in Spain and Vila Real de Santo António in Portugal.

The southernmost major river in Spain is the Guadalquivir, flowing through a rich agricultural region that forms the heartland of Andalusia. The region and the river enriched the city of Córdoba, the Corduba of Roman times, which later served as a principal Islamic city and the capital of the Islamic caliphate in Spain from the tenth to the eleventh centuries. Its mosque and other cultural monuments make modern Córdoba a major destination for cultural tourism.

In historic times, ships could travel on the Guadalquivir as far upstream as Córdoba. Today, ocean-going vessels can only travel as far upriver as Seville, where important episodes have played out in every period of Spain's history. Legendarily founded by Hercules and likely established by Julius Caesar, the city the Romans called “Hispalis” later became the capital of a major Muslim kingdom. Its reconquest in the thirteenth century assured Christian control of the Guadalquivir valley. Seville was the official port for all traffic to Spain's American empire in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and retains a rich architectural legacy from that period. The Guadalquivir reaches the Atlantic at the Bay of Cádiz, which takes its name from its major city, the oldest in Western Europe.

Iberia has two distinct areas of climate, one rainy and the other semi-arid. The wetter region, which geographers call the pluvial zone, encompasses most of the north coast and the northern half of the western coast, from Lisbon northward through Galicia. The region has cool summers, mild winters, and frequent rain throughout the year. The verdant hillsides seem to promise good growing conditions for crops, but in fact the hills, valleys, and overabundant rain in Galicia have hindered grain production through the centuries, forcing its inhabitants to rely on the sea and to import food and export people. The semi-arid remainder of the peninsula shares a climate with its Mediterranean neighbors, with mild winters along the coast and colder and more severe winters in the interior. Summers are hot and dry, and the other seasons bring unpredictable rainfall.

Variations in wind and rainfall year by year and decade by decade depend largely on changes in the path of the westerly winds over the North Atlantic Ocean. These winds pick up warm, moist air as they pass over the Gulf Stream and deliver rain to Europe, more in the north and less in the south. Changes in the path of the westerlies result from alterations in the systems of sea-level atmospheric pressure. There are permanent areas of low pressure in the north and high pressure in the south, usually known as the Icelandic low and the Azores high (or, sometimes, as the Bermuda high in the western hemisphere). The variations in pressure and the relations between the two systems make up a system called the North Atlantic Oscillation. When the pressure in the north is relatively low compared with much higher pressure in the south, that is known as a high North Atlantic Oscillation index. It allows the westerlies to blow strongly into Northern Europe, bringing cool summers and mild winters and increased rain to that region, whereas the Mediterranean region tends to be drier. When pressure is higher in the north and the Icelandic and Azores pressures are close to one another, this defines a low North Atlantic Oscillation index. The westerlies then reach Europe farther to the south than usual, allowing north and northeast winds to bring cold weather into northwest Europe and stormy, wet weather into the Mediterranean lands.

The story of human habitation in the peninsula has unfolded against a background of the constraints represented by the environment and its notable extremes of topography and climate. At the same time, Iberia's position between two continents and bordering two seas has meant that human populations have had relatively easy access to the peninsula. These population movements into Iberia over thousands of years played a major role in shaping both its prehistory and its history.

The fossil remains of the earliest Europeans found to date rest in northern Spain, east of the city of Burgos in the Sierra de Atapuerca. These remains suggest that a population of hominids (of the genus Homo) has been living in the peninsula for over a million years. Though such a population seems very ancient, it is fairly recent among hominid remains, some of which date as far back as seven million years in Africa. Early humans began to leave Africa by the northeast, with the earliest waves making their way into Asia. Somewhat later, some groups began to migrate west into Europe. They were certainly in the Caucasus Mountains by around 1.7 million years ago.

That Atapuerca became a center for the study of early humans in Europe happened almost by chance. Gold mining in the area during the nineteenth century impelled the Sierra Company, a British enterprise, to build a railway from Burgos to the mines. One deep cut went through the Sierra de Atapuerca, exposing ancient layers of sedimentation. After the mines gave out and the railroad fell into disuse in the 1920s, animal and human remains eventually appeared. The first and most important find, at a site called the Sima del Elefante (“Pit of the Elephant”), occurred in 1976 with the discovery of human teeth and part of a jawbone, dated by experts to be as old as 1.2 million years.

The abundance of slightly more recent bones at Atapuerca, particularly at the Gran Dolina site, have allowed archeologists to build a full picture of life in the area over three-quarters of a million years ago. The inhabitants lived by scavenging and hunting some twenty-five species of animals, including large ones such as rhinoceros, mammoth, and bison. They butchered the animals and disposed of their bones in the cave. They did the same for humans, making the hominids at Atapuerca some of the earliest documented cannibals.

Near the Gran Dolina, archeologists also investigated the Sima de los Huesos (“Pit of Bones”), where they found, in addition to the bones of animals, the largest assemblage of ancient hominid bones found anywhere in the world: some thirty individuals, along with one well-preserved ax head. These individuals lived much later and were probably unrelated to those in the Gran Dolina. The remains have been identified as examples of Homo heidelbergensis (“Heidelberg man”), a species active in that part of Spain some 400,000 years ago, during the Old Paleolithic period (500,000 to 100,000 years ago). The thirty individuals found in the Sima de los Huesos were all in their late teens or twenties and showed signs of injuries. They seem to have been placed intact in an uninhabited cave. Whether this signifies a deliberate burial of the dead or a simple disposal of individuals killed in some form of combat remains open to speculation.

Later groups of hominids also entered Spain. Neanderthals arrived around 200,000 years ago and established settlements scattered throughout the peninsula. In fact, Neanderthal remains were first discovered at Gibraltar in 1848, but their identification as a separate species came later, when other fossil material turned up at Neanderthal in Germany in 1856. Scientists once thought that the Neanderthals died out around 35,000 years ago, but they may have survived in the Iberian Peninsula for much longer: Neanderthal remains have been found in Gibraltar that date to as recently as 24,000 years ago.

These various finds show that Neanderthals in Iberia coexisted with other Stone Age cultures, including representatives of modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) who settled throughout the peninsula during the Upper Paleolithic period (45,000 to 10,000 years ago). The earliest dated from some 35,000 years ago, representing members of the Aurignacian culture, widespread in Europe. They brought improved implements on their migrations, notably tools of bone, antler, and flint. They likely sewed skins and furs together for clothing, because archeologists have found needles for that purpose among their remains. The Solutreans, coming from North Africa and bringing the hunting bow with them, replaced the Aurignacians in Iberia about 20,000 years ago. In turn, the Magdalenian culture, which came from Northern Europe and whose hunters pursued reindeer, displaced the Solutreans about 17,000 years ago. Finally, the last Paleolithic culture replaced the Magdalenians in Iberia about 10,000 years ago.

Archeological sites from these Paleolithic cultures abound throughout the Iberian Peninsula, including many with cave paintings. Perhaps the most famous is at Altamira in northern Spain, on the low coastal plain at the center of the Cantabrian coast. The Upper Paleolithic cave paintings of Altamira are some of the best examples found thus far and date from 18,500 to 14,000 years ago. Produced by using locally obtained pigments mixed with animal fat, they depict food animals – horses, bison, red deer, and reindeer, among others – in various poses, some of them wounded. Scholars debate the significance of the paintings. They likely were not for decorative purposes, as they appear far back in the cave, isolated from the inhabited portions near the entrance. Perhaps the paintings figured in initiation rites for young hunters. Perhaps they represent attempts to establish spiritual and material links between the group and their food supply. Certainly they are some of the best early realistic paintings in all of human history.

The animals depicted in the cave paintings were well adapted to the conditions of the last ice age and they tended to become scarcer when the climate warmed significantly some 12,000 years ago. Warming temperatures across the world melted Arctic ice and glaciers in the northern hemisphere, thereby flooding coastal lowlands. In the Iberian Peninsula, as the animal populations decreased, the Stone Age cultures turned toward gathering shellfish along the coasts for their sustenance.

Around 8,000 years ago, Neolithic (New Stone Age) peoples entered the peninsula; they with them better stone tools – hence their name – but, more importantly, early techniques of agriculture and animal husbandry. With their arrival, the pace of change in the human population quickened, and the newcomers displaced older human groups. Supported by agriculture, as well as hunting and gathering, they were able to form larger communities and to live a more settled existence.

About 3,400 years ago, copper tools appeared in the peninsula, and along with them evidence of copper mining and smelting. The most important archeological site for this period is Los Millares, near Almería in southeastern Spain. Most Copper Age sites include fortifications and carefully constructed stone tombs. By around 2,200 years ago, Bronze Age groups made their appearance in Iberia. Metal deposits exist in many parts of the peninsula, including gold deposits in river sands, copper in the south, and silver in the west. Sources of tin exist in both the south and the northwest. Lead and iron deposits are located in the same general areas as tin, though human groups did not mine them as early. Scientists have identified two Bronze Age cultures in Spain, one along the Mediterranean coast, and the other along the Atlantic coast, presumably related to the incursions – respectively – of the Iberians and the Celts.

The Iberians entered Spain from North Africa, possibly with eastern origins, and spread along the Mediterranean coast. They brought with them knowledge of agriculture, mining, and working metals, including bronze. They also worked stone, using large blocks for construction, and carving blocks for statues, most notably the so-called “Dama de Elche.” From the merchants of the Mediterranean, they learned writing and the coining of money and developed a written language whose alphabet derived from Greek and Phoenician. The Iberian language is now mostly lost, except for inscriptions on stone and lettering on coins. Celtic culture came in a series of waves with peaks in the ninth and seventh centuries BCE. Coming from the north, the Celts entered Iberia via the western Pyrenees and spread along the Atlantic coast, supporting themselves primarily by herding. Toward the end of the Bronze Age, knowledge of working iron spread through the Celtic region. For generations, scholars assumed that the spread of Celtic culture was due to movement of peoples. Recent specialists have suggested that a diffusion of ideas and techniques, rather than migration, was probably more responsible.

However they spread, Celtic and Iberian cultural forms influenced local peoples and, in the center of the peninsula, blended with one another to produce a composite culture that Greek and Roman writers described: the latter called them “Hispani.” They had a warrior aristocracy at the top of their society and a free class of workers beneath them. Further down the social scale were slaves, usually prisoners of war but also individuals who had voluntarily given up their freedom in exchange for the protection of a local strongman. They had no large kingdoms but instead grouped themselves in independent cities ruled by elites. Their settlements tended to be on fortified hillsides or in fortified villages on the flat lands of the Southern Meseta. Various cities formed temporary alliances in times of danger but resisted long-term associations. Economically, they practiced herding and agriculture. They also produced ceramics, cloth from wool and linen, iron weaponry, and baskets. Mining the metal resources in their areas gave them a product to trade with the merchants from the Mediterranean and elsewhere.

Southwestern Spain became a major nexus for the Atlantic Bronze Age, with its people exchanging Iberian metals with northwest Europe for tin, which they combined with native copper to make bronze. The Atlantic coast of southwest Iberia was the site of the legendary place called Tartessos that figured in mythology from the Greeks forward. It was the scene of some of the labors of Hercules, later considered to be one of the founders of Spain. According to legend, Hercules split apart Europe and Africa and created the Strait of Gibraltar, known to the ancients as the Pillars of Hercules. In Greek legends, Herakles (Hercules) is supposed to have tended the cattle of Geryon, the king of Tartessos. The Greek historian Herodotus (fifth century BCE) related stories about Arganthonios, another ruler of Tartessos, and noted the region's richness in metals. Traditionally described as a city, Tartessos is more properly the name of the region along the lower reaches of the Guadiana and Guadalquivir rivers and of the indigenous people who settled and developed the area. Tartessos became a famous ancient center of trade and eventually attracted Phoenician invaders, who ultimately conquered it.

The interest of Mediterranean merchants in Spain began with the Phoenicians around 800 BCE. They, and later the Greeks and the Carthaginians, established a series of trading posts that the Greeks called clerukia. With relatively large populations – 1,000 or so in each settlement – their main purpose was to trade with local suppliers and send goods back to their home areas. The merchants were interested primarily in the ordinary and precious metals that abounded in Iberia, including silver, copper, and lead. They were also interested in the produce of the sea. Lacking refrigeration, the peoples of the ancient Mediterranean world used other means to preserve food. After bringing fish ashore, they would clean and dry some of the catch for sale. From some species, they would remove the fillets, dry and salt them, and thus be able to trade them widely without losing much to spoilage. They also made use of the skin, bones, and entrails of the catch, which they processed in large stone vats in the sun. With salt and spices added, the mixture would steep, ferment, and eventually form a thick sauce called garon, that kept well and could therefore be transported long distances.

Ancient Mediterranean merchants traveling to Spain were also interested in timber, because many parts of the Mediterranean world are semi-arid and faced constant problems in finding adequate supplies of wood. Peoples living around the Mediterranean had to manage their forests very carefully, and some areas in the Mediterranean basin do not produce forests at all, forcing inhabitants to import what timber they needed. The Phoenicians were in that latter category and sought timber in Spain. Tradition holds that Phoenicians founded the city of Cádiz in 1100 BCE, giving it a history of over 3,000 years. Almost assuredly, the foundation occurred later, after 800 BCE. Even so, Cádiz is Western Europe's oldest city, known to its founders as Gadir, a name the Romans changed to Gades.

In addition to Cádiz, the Phoenicians founded other trading bases in southern Iberia, including Malaca (Málaga) and Onuba (Huelva) on the southern coast, and an outpost on the island of Ibiza. Resident agents of businesses based in the Phoenician home cities – mainly Tyre and Byblos – lived in these outposts and traded wares such as gold jewelry and Greek pottery. Phoenician colonies in Iberia even weathered the subjugation of their home cities by the Babylonians in the sixth century BCE. They remained active in Iberia and connected with the new trading system organized by the Carthaginians, themselves of Phoenician origin.

After the Phoenicians, other outsiders began to form communities in Iberia. Even before the Greeks themselves arrived, their goods – pottery and bronze – were common in Iberia, brought in by the Phoenicians. The Greeks reached Iberia as an outcome of their pattern of expansion in the ancient period. Their ancient home in the Balkan Peninsula is even more mountainous than Iberia and has a limited amount of good grain land. As their population grew, the Greeks planted colonies far from Greece proper, in a process sometimes called “budding.” A group of people from an overpopulated Greek city-state would move elsewhere and establish a daughter-city, whose people would share and maintain the customs of the mother-city. Following this custom, the Greeks colonized all of the shoreline of Anatolia; the area around the Black Sea, especially its southern shore; southern Italy and Sicily; southern France; and finally eastern Iberia, where they established a major presence. Most of the Greek colonies in the western Mediterranean were founded from the major settlement at Massalia (modern Marseille).

After setting up several trading stations along Spain's Mediterranean shore, Greek colonizers founded the first true Greek city in Iberia around the sixth century BCE, and called it Emporion. The name relates to the English word “emporium,” a place where trade is conducted, and that seems to have been its major function; it became the most important of the Greek city-states in eastern Iberia. The Romans called it Emporiae. In modern times, Spaniards call the area's major city Ampurias, and Catalans call it Empuries.

The Greeks and the Phoenicians introduced a number of important plants to Iberia, among them the grapevine and the olive tree. From the time of their introduction until the present day, these well-adapted plants made Spain a major producer of wine and olive oil. The olive tree will grow in about two-thirds of Spain – the warmer and more arid regions. It requires some rain, of course, but it requires above all sunlight and warm winter temperatures. Olive trees will not grow in the pluvial, or rainy, regions of the north and northwest, because the temperatures are not warm enough in the summer and rain is too abundant year-round. In modern times, olive trees grow nearly everywhere in Spain that the climate can support them, but their main region is the southern quarter of the peninsula, where one can see vast areas stretching in every direction with almost nothing but olive trees. The Greeks and the Phoenicians also brought writing into the Iberian Peninsula, and the Iberians probably learned their alphabet from the Phoenicians. The Greeks also brought metal coinage, primarily in silver, and the Iberians learned from them how to produce their own coinage.

The people of Carthage also established themselves in Iberia. Carthaginians were descendants of the Phoenicians and continued the Phoenician tradition of trading in the western Mediterranean, into North Africa, and into the Iberian Peninsula. They also established a colony on the island of Ibiza (Ebusus). Carthage sat across the Mediterranean from Rome, and its remains are close to the modern city of Tunis. The Carthaginians and the Romans became rivals for a number of reasons, but particularly over possession of Sicily, a very prosperous and productive island in the ancient period. It was a breadbasket for the central Mediterranean and exported wheat in various directions.

The Carthaginians also came to think that they could establish a large presence in the Iberian Peninsula, a decision that intensified their long-term struggle with the Romans. A family of Carthaginian generals and highly placed politicians called the Barcas coordinated much of the Carthaginian activity in Iberia. Hamilcar Barca suggested to his superiors that Spain would be a good counterweight to Rome. He entered Spain in 236 BCE with a Carthaginian army and virtually independent military authority, perhaps with the objective of conquering all of Spain. Some local leaders and city-states joined with Barca; others did not, but he achieved some success and a series of notable conquests during his career. Hamilcar Barca built a number of fortresses in Spain, some of which grew into cities. One town at the southeastern tip of the Iberian Peninsula was among the most successful. The Romans would call it Nova Carthago (New Carthage), and modern Spaniards call it Cartagena.

At the time when Barca entered Spain, there was no unified political authority. Instead, various city-states and tribal groups lived in more or less disconnected areas throughout the peninsula, in addition to various Greek cities and trading posts on the Mediterranean coast. The Greek enclaves in Spain each had close ties to their home cities and to Rome, but they functioned as independent entities. The Romans made separate treaties with the Greek enclaves in Spain, whose leaders essentially paid for Roman military protection in case they were attacked. The Romans also made an agreement in 226 BCE with the Carthaginians, establishing the Ebro River as the division between their spheres of influence in Spain, with the Romans to the north and the Carthaginians to the south.

The Romans became increasingly interested in Spain because of Carthaginian activities there. Matters reached a critical point in 209 BCE, after Hamilcar Barca's son Hannibal attacked Saguntum, a town south of the Ebro – technically in the Carthaginian sphere. Saguntum's leaders had nonetheless appealed to Rome for help, but, as Hannibal besieged the town, Roman help failed to arrive. The townspeople defended themselves to the last man, and their efforts became famous in Spanish history as a tale of endurance and patriotic sacrifice. Only after the siege ended did Rome prepare for full-scale war against Carthage.

By the time the Romans were ready, Hannibal had launched an invasion of Italy from Spain, entering Gaul and crossing the Alps in the winter with his troops and war elephants. He won some engagements against Roman forces, but Rome ultimately prevailed. Under Publius Cornelius Scipio, the Roman army drove the Carthaginians from Spain in 206 BCE. Four years later, Scipio's forces put an end to the Second Punic War at the battle of Zama in North Africa, near Carthage, and for that victory he acquired the name Scipio Africanus. The Romans then had to decide what they would do with the places they had won from Carthage in Spain.

The Picos de Europa (Peaks of Europe, Cantabria) represented a formidable obstacle to communication between interior regions and the northern coast for much of Spanish history.

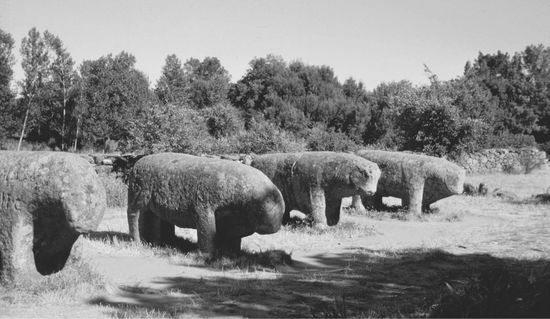

Many scholars think that the so-called “Toros de Guisando” (Bulls of Guisando) near Ávila date from the second century BCE, and that the Romans moved them to their present site.