Hullo. As you probably know I’ve been away at a conference in Paris sorting out the final details of the merger between our company Heathco’s and the large continental combine E.E.C. Ltd. …

I would like to state categorically once and for all: THIS NEW ARRANGEMENT DOES NOT, I REPEAT, NOT, MEAN THAT WE ARE GOING TO BE TOLD WHAT TO DO BY A LOT OF FOREIGNERS.

E. Heath, Managing Director.

Private Eye, 3 November 1972

The town of Broadstairs, nestling on the tip of the Isle of Thanet on the eastern edge of Kent, has always been a link between England and the Continent. The Romans landed on the Isle – which was then detached from the Kentish mainland – in 55 BC, and returned under Claudius a hundred years later. In the fifth century, Hengist and Horsa, by legend the first of the Anglo-Saxons, are said to have settled on the Isle of Thanet, and Viking raiding parties twice wintered in the area centuries later. By the fourteenth century, a little fishing village called Bradstow – Old English for ‘broad stairs’, after the steps men had cut in the soft chalk cliffs – had been established above the broad golden sands, eventually coming under the jurisdiction of the Cinque Ports. It was associated above all with fishing and shipbuilding, and was no stranger to foreign visitors: during the 1600s, Flemish refugees settled in Reading Street, while the town’s stout sea walls testified to the fears of invasion from the south. In 1723, Daniel Defoe recorded that the town’s population were generally fishermen, although he noted that Broadstairs was also renowned as a ‘hot bed of smuggling’. Seventy years later, the town gates were urgently repaired to cope with a possible invasion from revolutionary France, and it was at Broadstairs that the imperial French eagle captured at Waterloo was brought onto English soil. And local legend has it that Broadstairs was the first English community to hear the news of Wellington’s great victory – though this was a tale that the town’s most famous son tactfully kept quiet about with his European friends.1

When Teddy Heath was growing up in Broadstairs in the 1920s, his parents used to take him for walks on the cliffs, from where on a clear day he could see the faint grey smudge of Calais and the French coast. Even as a boy, Heath was fascinated by the distant lands to the south. His father, Will, was a typical introverted Englishman, quiet, solid and serious, but his mother had travelled to Switzerland as a lady’s maid before her marriage, and told stories of the voyage to her children. When Teddy was 14 he had the chance to follow in her footsteps, joining a school trip to Paris – a real treat by the standards of the day. Years later, he fondly recalled the details of the great expedition: the flight from Croydon Airport, then something that few people had ever done; the extraordinary variety of Parisian restaurants, each with its own outdoor menu to intrigue the young visitors; the ‘magnificent shops’ and motor showrooms, whose catalogues he kept even as an old man; the performance of Carmen at the Opéra Comique, where he remembered seeing an attractive blonde woman in the box below struggling to keep her shoulder straps up as they ‘repeatedly slipped down in a most revealing fashion’; and perhaps above all, his illicit trip to the Folies-Bergère with some friends when they were supposed to be tucked up in their boarding house – a detail he somehow forgot to mention when he eagerly told his parents all about the trip afterwards.2

From that moment on, Heath was hooked. As a student at Oxford in the late 1930s, he seized every opportunity for travel, spending one summer in Republican Spain and another on an extraordinary tour of Nazi Germany, where he spent many happy hours in Munich’s art galleries and concert halls and also had the unusual experience of listening to Hitler at a Nuremberg rally. Afterwards, the young Heath was invited to an SS cocktail party where he was introduced to Goering (‘far more bulky and genial than I had imagined’), Goebbels (‘small, pale and, in that setting, rather insignificant-looking’) and Himmler (‘I shall never forget how drooping and sloppy [his] hand was when he offered it to me’). Two years later, in the summer of 1939, he was on a hitch-hiking tour of Berlin, Danzig, Dresden and Leipzig when news broke of the Nazi–Soviet Pact. Taking the first train out of Germany and hitching to the Channel, he arrived home in Kent only a week before Hitler invaded Poland. He did not return to his beloved Europe until June 1944, when he sailed to France as an officer in the Royal Artillery Corps, and crossed the Rhine into Germany just before VE Day. After his regiment moved into Hanover, he made it his first priority to rebuild the local opera house. ‘My men must have culture,’ he told his Brigade Commander. But perhaps the most memorable incident in Heath’s war came months later, when he returned to the blackened ruins of Nuremberg to watch the trials of the Nazi war criminals. It was an experience that left a deep imprint on this stiff, shy but impressionable young man:

As I left the court I knew that the shadow of those evil things had been lifted, and their perpetrators now faced justice. But at what a cost. Europe had once more torn itself apart. This must never be allowed to happen again. My generation did not have the option of living in the past; we had to work for the future. We were surrounded by destruction, homelessness, hunger and despair. Only by working together right across our continent had we any hope of creating a society which would uphold the true values of European civilisation. Reconciliation and reconstruction must be our tasks. I did not realise then that this would be my preoccupation for the next fifty years.3

Whatever one thinks of Heath’s European commitment, there is no doubt that it was thoroughly genuine. His maiden speech as an MP in 1950 was devoted to the Schuman Plan for a European Coal and Steel Community, which became the nucleus of the modern European Union. At a time when many British politicians insisted on staying aloof from schemes of European collaboration, Heath was all for it, insisting that ‘we may be taking a very great risk with our economy’ by staying out. Characteristically, he had just returned from a fact-finding trip to West Germany; trips to the Continent were to be a constant feature of Heath’s parliamentary career, and he often seemed more comfortable with French and German contacts than with his own party comrades. When Macmillan picked him to handle Britain’s first application to join the six members of the Common Market in 1961, it soon become clear that there could be no better candidate. At the very beginning, Heath told the European negotiators that the application was ‘a great decision, a turning point in our history’, and his enthusiasm made a profound impression both on his own civil servants and on the representatives of the Six. And when President de Gaulle, in a stunning exhibition of diplomatic cunning, self-interest and spite, vetoed the British application in January 1963, Heath gave what was probably the speech of his life. Rejecting the view that Britain was ‘not European enough’, he told the assembled foreign ministers that there were ‘many millions in Europe who know perfectly well how European Britain has been in the past and are grateful for it’. They should ‘have no fear’, he said. ‘We in Britain are not going to turn our backs on the mainland of Europe or on the countries of the Community. We are a part of Europe: by geography, tradition, history, culture and civilisation. We shall continue to work with all our friends in Europe for the true unity and strength of this continent.’ It was the only time in his life that this most wooden of speakers managed to move an audience to tears: when he had finished, even the female interpreters were discreetly dabbing their eyes.4

By the time Heath became Prime Minister, Britain had suffered the humiliation of yet another veto from de Gaulle, this time after a self-deluding and characteristically semi-ridiculous application (technically called ‘the Probe’) by Harold Wilson and George Brown in 1967. Revealingly, neither of the failed bids was especially popular with the public, and, even more revealingly, both were the products of desperation rather than conviction, born out of political and economic weakness. Macmillan only decided to apply to join the Common Market once his government had run into trouble and commentators were attacking him as backward and reactionary, while Wilson only applied once his ambitions to revive Britain as a white-hot technological powerhouse had been destroyed by the 1966 sterling crisis. The irony was that if Britain had joined the Common Market in the mid-1950s, as its European neighbours had hoped, then it would have done so as a military and economic superpower, still unquestionably Western Europe’s pre-eminent nation. But by 1970 no serious observer could pretend that Britain still set the standards for the rest of the Continent. In productivity growth, for example, it had fallen behind not only the astonishingly industrious West Germans but the supposedly lazy French and Italians, while its GDP growth rate was just half that of the five major EEC countries (France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium and the Netherlands). On top of that, while Britain’s share of world exports had collapsed from 26 per cent in 1950 to less than 11 per cent in 1970 and barely 10 per cent in 1980, West Germany’s share soared from 7 per cent in 1950 to 20 per cent in 1970 and 30 per cent by 1980. From the mid-1960s onwards, in fact, Britain cut a very miserable and unimpressive figure beside the buoyant French and West Germans. It was true that the French had their problems with student unrest and the Germans with domestic terrorism; but then Britain had plenty on its plate in Northern Ireland. And not only was unemployment much higher than in France and West Germany, but Britain’s inflation record was truly abysmal. The Germans might be unhappy with an inflation rate of 6 per cent in 1975; but they had only to look across the Channel, where it had reached almost 25 per cent, to remind themselves that they must be doing something right.5

When Heath won the election in 1970, it was common knowledge that he planned to apply for Common Market membership as soon as possible. This was not merely a personal project, though; it was a vision shared by almost all senior Conservatives. The party’s detailed report recommending European entry, for example, had actually been prepared under Heath’s predecessor, the strongly pro-American Sir Alec Douglas-Home. But as with other emotive issues of the late 1960s such as immigration and the abolition of capital punishment, there was a strong whiff of elitism about pro-Europeanism. Not only were most Tory associations dead set against entering the Market, but most Tory voters were very sceptical, too. Throughout the 1960s, in fact, public opinion had been a mixture of indifference, confusion and outright hostility, with support rallying only whenever the British economy seemed particularly dire. In April 1970, just weeks before the election, Gallup found that just 19 per cent of voters supported British entry, with more than 50 per cent rejecting even the idea of holding talks. On the other hand, most business leaders strongly backed the idea of entering a bigger European market, and the CBI was particularly enthusiastic: a year later, a survey of 1,000 firms found that 95 per cent backed joining the Common Market. The civil service was broadly enthusiastic, too, with the notable exception of the Treasury. And although Heath’s drive to win British membership is often seen as one man’s lonely crusade, the truth is that his successes were built on foundations laid by others. He actually inherited much of the team that organized the bid from Harold Wilson; all the files were prepared, all the planning was in place, and a lot of work was already out of the way. Indeed, one of the little secrets of British politics in the early 1970s was that Wilson had been planning a new bid once he won re-election. The Labour government had even fixed a date for negotiations to begin, which makes Wilson’s decision to turn against Europe immediately after his defeat look even more cynical and unprincipled.6

What distinguished Heath from his contemporaries, therefore, was not the commitment itself but its unusually personal nature, rooted not just in his travels on the Continent but also in his deep love for its musical heritage, his contacts with European politicians and his experiences during the Second World War. Harold Wilson might have applied to join the Common Market in 1967, but he said himself that he had ‘never been emotionally a Europe man’, while his policy adviser Bernard Donoughue observed that Wilson was ‘basically a north of England, non-conformist puritan … continental Europeans, especially from France and southern Europe, were to him alien. He disliked their rich food, genuinely preferring meat and two veg with HP sauce.’ This even extended to holidays, which Wilson famously spent on the Scilly Isles, as well as to cheese. After one Downing Street lunch, Donoughue recorded that Wilson had been delighted to have English cheese, because he much preferred it to French.7

But then Wilson was also a fan of the Commonwealth, in which Heath took no interest whatsoever. And Wilson was strongly pro-American to the extent of modelling himself on first John F. Kennedy and then Lyndon Johnson, whereas Heath was unusual among modern British prime ministers in his total indifference to all things American. The irony was that although Johnson treated Wilson as an inconvenient but obsequious nuisance, the next President, Richard Nixon, was hugely excited by Heath’s victory and hoped that they would become great friends. Like Heath, Nixon was a conservative modernizer from a humble provincial background, a self-made man distinguished by his lofty vision, brooding intellect, grumpy demeanour and permanent social unease. In some ways they should have been natural soulmates – they could have bonded, for instance, over their shared interest in classical music, their mutual disregard for women, or their fondness for wildly overcomplicated incomes policies. To Nixon’s bewilderment, however, Heath rebuffed his attempts to strike up a special relationship. Henry Kissinger, Nixon’s supremely cynical Secretary of State, wrote later that they were shocked by Heath’s ‘unsentimentality’ and ‘reserve’, which left Nixon feeling like a ‘jilted lover’. But Heath had no time for misty-eyed visions of Anglo-American partnership. All the special relationship achieved, he said later, was ‘to estrange us from our European colleagues … Now there are some people who always nestle on the shoulder of an American president. That’s no future for Britain.’8

In his profound affection for European culture and complete lack of interest in anything American, Heath cut an unusual figure among contemporary British politicians. And yet although there had been plenty of anguished commentary about the supposed ‘Americanization’ of British life in the 1950s and 1960s, from supermarkets and advertising to fast food and television, what was much more striking was the extent to which Britain was becoming ‘European’. The pop act that recorded most number one hit singles in the 1970s, for example, was not Rod Stewart, Elton John, the Bay City Rollers, the Sex Pistols or any other emblematic British singer or group of the day; it was a Swedish group, Abba, who sang in heavily accented and occasionally slightly strange English. Admittedly they made their great breakthrough in the unmistakably English surroundings of the Brighton Dome, built in 1805 for the Prince Regent and connected to the famous Pavilion, but the occasion was distinctly European: the nineteenth Eurovision Song Contest, held in April 1974. In many ways the contest was a typical product of the 1950s, conceived as a well-meaning effort to bring old enemies together, although more often than not it merely exposed the depths of Continental depravity – for example in 1968, when Cliff Richard was disgracefully cheated of victory by Franco’s vote-rigging. By the early 1970s, however, it was a serious business, commanding international viewing figures unequalled by anything other than major sporting events. The BBC took it so seriously that in 1971, when the contest was held in Dublin, they deliberately chose a Northern Irish singer, Clodagh Rogers, to minimize Anglo-Irish tensions (although she still got death threats from the IRA). Indeed, terrorism was a constant concern: when the contest was held in Stockholm in 1975, the authorities took massive precautions against a rumoured attack by the Baader–Meinhof Group, and at the eighteenth edition, held in Luxembourg and the first to feature an Israeli entry, the audience were memorably advised not to stand up while applauding in case they were shot by the security forces. Mercifully, the Brighton event was free of any such horrors, although it did feature a half-time performance by the Wombles.9

Although Abba’s success obviously depended on their talent for writing irresistibly catchy songs, they were not the only example of European infiltration into the British charts. When the abominable ‘Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep’ topped the charts for five weeks in the summer of 1971, for example, the most common explanation was that people were trying to recapture the spirit of their holidays in Spain, where it had been everywhere that summer. In fact, it had been recorded for the Italian market by Middle of the Road, a Scottish pop group who specialized in Anglo-Latin crossovers, and even they thought it was awful. Their drummer later remarked that they needed two bottles of bourbon before they could start work, for ‘we were as disgusted with the thought of recording it as most people were at the thought of buying it’. But three years later, the curse of the Armada struck again, this time in the form of the Swedish singer Sylvie Vrethammar, whose hit ‘Y Viva España’ – ‘This year I’m off to sunny Spain …’ – captured the excitement, the hedonism and the sheer awfulness of package tourism in its early years.10

As a Broadstairs boy, Heath was well placed to appreciate the seismic changes that had overtaken British holiday habits. Like so many seaside resorts, the little Kentish town had long relied on a flood of big-city holidaymakers in the summer months; Charles Dickens, for example, was a great fan, visiting almost every year from 1837 to 1859. By the early 1970s, however, resorts like Broadstairs were losing their lustre, outshone by the new craze for touring caravans, the newfound popularity of more distant stretches of rural England such as Devon, Cornwall and the Lakes, and above all, the sun-bleached concrete monoliths of Torremolinos and Benidorm. Heath himself chose to take pride in the changing patterns of tourism: in the official programme for the ‘Fanfare for Europe’ celebrations in January 1973, he expressed his delight that ‘many more of us in Britain, in particular young people, travel to other European countries than a decade ago’, with holidaymakers becoming ‘steadily more “European” in terms of our knowledge and contacts’. But it was resorts like Broadstairs that paid the price in boarded-up shop-fronts, abandoned amusement arcades and crumbling hotels. Already Northern resorts like Skegness and Cleethorpes, with their wet and windy reputations, were struggling for custom. On the Wirral, the resort of New Brighton fell into total disrepair, with its ballroom ravaged by fire in 1969, ferries across the Mersey discontinued in 1971, and the promenade pier torn down six years later. Even the fictional seaside town of Fircombe in Carry On Girls (1973) is a miserable place of slate-grey skies, driving rain and empty hotels: in the film’s opening shots, we see a family sheltering from the rain in the shelter of a derelict pier, while a sign behind them reads ‘Come to Fabulous Fircombe’, with graffiti adding ‘What the hell for?’11

The sentiment would have appealed to the acerbic Tory politician Alan Clark, who was not impressed by the venue for their party conference in October 1973. ‘Isn’t Blackpool appalling, loathsome?’ he wrote in his diary. ‘Impossible to get even a piece of bread and cheese, or a decent cup of tea; dirt, squalor, shanty-town broken pavements with pools of water lying in them – on the Promenade – vulgar common “primitives” drifting about in groups or standing, loitering, prominently.’ It was no wonder that as soon as the conference was over, hundreds of Blackpool hoteliers decamped en masse to Spain, heading for the very resorts that were destroying their livelihoods. ‘It was like being in Blackpool except we had this wonderful sunshine,’ one later recalled. ‘It was November and the main topic of conversation was, “Amazing sun, isn’t it? We couldn’t do this in England.” ’12

The father of package tourism is often identified as the former Reuters journalist Vladimir Raitz, who flew thirty-two students and teachers in an old American Dakota to Corsica in 1950, with the intrepid pioneers staying in a makeshift camp of army surplus tents. By the end of the 1960s, his company, Horizon, was one of Britain’s biggest package operators, with tours to Majorca, Minorca and Ibiza, the Costa Brava, Costa Blanca and Costa del Sol, the Algarve, Bulgaria and Crete. At this stage, though, package holidays abroad accounted for barely 8 per cent of the total holidays taken by British families, partly because travellers were only allowed to take £50 a year out of the country. In January 1970, however, the rules were amended to allow individuals to take £25 each per trip, and from then on the boom seemed unstoppable. By 1971, British tourists were taking more than 4 million holidays abroad; by 1973, some 9 million; by 1981, more than 13 million. The two-week trip to Spain with Horizon, Cosmos or Thomson became a great status symbol of the mid-1970s: children who might once have been delighted by a few days in Bognor now pestered their parents to take them to Benidorm, desperate to keep up with their more affluent classmates.

For people who had grown up with the limited horizons of working-class life in the 1950s and 1960s, that first trip abroad was often an unforgettable experience, all the way from the endless, harried queues at the airport to the atmosphere on the plane itself, thick with anticipation and cigarette smoke, and then the shock of the heat, the light and the unfinished hotel. ‘Stepping off the plane at Ibiza airport was incredible,’ a clerk from Burnley recalled of her first trip abroad. ‘The doors opened, the heat flooded in and the smell of musk and pine mixed with cigar smoke … Unbelievable. Coming from a grey northern mill town, you can imagine when we saw all the lovely white painted houses with geraniums growing from the balconies, we felt we were in another world.’ And some holidaymakers reported that the experience made them look on their native land in an entirely new light. In June 1970, a reader who had recently visited the Spanish coast wrote to the Mirror noting that ‘there were no aggro boys, no vandalism, all the telephone boxes were clean and all the phones worked. It was hardly necessary to lock up cars and little children could go anywhere unmolested.’ Four days later, another reader wrote in. ‘I appreciate that he did not see any aggro boys,’he commented wryly, ‘but did he notice the armed police, the censored press, the jails crowded with people who merely expressed their dislike of the Franco regime?’13

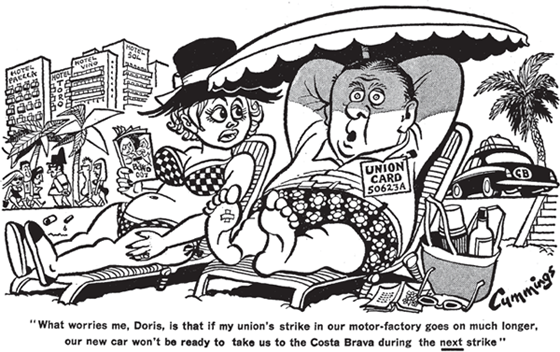

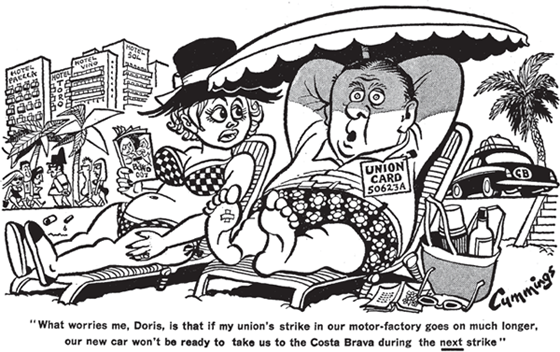

Holidays on the Spanish coast were becoming the norm as early as 9 August 1970, when Michael Cummings drew this Daily Express cartoon mocking the selfishness of the unions.

Not all British holidaymakers enjoyed the Continental experience. Arthur Scargill, who usually took his holidays in Cornwall, eventually plucked up the courage to take his family to the socialist paradise of Bulgaria, but the overcharging and petty corruption infuriated him so much that, on his return, he announced: ‘If that’s Communism, they can keep it.’ A more common complaint was that with package companies overwhelmed by the demand, their planes were often scheduled to make two or three return journeys from Britain to Spain a day, with no room for manoeuvre when things went wrong (as they invariably did). In the early 1970s, delays of half a day or more were extremely common: the managing director of Gaytours later admitted that ‘if a flight was six hours late, that was good’. And with few organizations to fight for holidaymakers’ rights, service was often downright abysmal: one woman who flew for the first time from Birmingham to Majorca in the early 1970s later recalled that water leaked onto her shoulder throughout the flight, the pull-down table ‘came off in my hands’ and when the steward tried to wheel a duty-free trolley through the cabin, one of the wheels fell off and rolled down the aisle. ‘Of course we never complained,’ she mused. ‘Most people never dreamt of complaining in those days.’

But times were changing. In 1969, the BBC launched its weekly Holiday series, which was often devoted to scandals and scams, and in 1974 ITV followed suit with Wish You Were Here. Non-existent hotels, beaches that looked nothing like the picture in the brochure, surly locals and atrocious plumbing were all common complaints, but the dark side of the package experience was rarely better captured than in the film Carry On Abroad (1972), in which the familiar team visit the ‘paradise island’ of Elsbels, courtesy of the optimistically named Wundatours. In traditional fashion, their hotel is not quite finished; the drawers have no bottoms, the electrical fittings explode when turned on, and the taps produce sand, not water. They have no need of alarm clocks, either; every morning they are woken by a dawn chorus of pneumatic drills and cement mixers, which for all too many British visitors was an even more unforgettable part of the Mediterranean soundtrack than the songs of Middle of the Road and Sylvie Vrethammar.14

In Carry On Abroad, the British visitors themselves are hardly models of good behaviour. After a drunken night out in the local town, the entire tour party ends up in the cells, winning their release only after one of the women seduces a policeman. Unfortunately, this was less far-fetched than it sounded; drunk with the heat, the sense of freedom and the local liquor, many holidaymakers did drop their inhibitions in a way that would have been unthinkable at Broadstairs. A common stereotype of British tourists was that women were particularly liable to lose their self-restraint on holiday, opening their arms to the first smooth-talking Don Juan they bumped into. ‘Once they bridge that strip of English Channel,’ says Terry Collier in Whatever Happened to the Likely Lads?, ‘they drop everything: reserve, manners, morals and knickers’ – and this, of course, was before the heyday of Faliraki and Magaluf. But there was also a hefty dose of class prejudice in all this. Social class still played a large role in determining where people went on holiday: according to the British Home Tourism Survey in 1978, manual workers were far more likely to visit seaside resorts, while professional families were more likely to go on ‘country holidays where mountains and moorlands, lakes and streams are the attraction’. And as early as the mid-1970s, mass working-class tourism had become the subject of savage social commentary. In The Golden Hordes (1975), Louis Turner and John Ash complained that package holidays were reducing the Mediterranean to a vast ‘pleasure periphery’, with all sense of cultural distinctiveness submerged beneath a mountain of cheap souvenirs and a vast flood of baked beans, sun-tan lotion and pints of Skol. Tourists were the ‘new barbarians of our age of leisure’, they wrote, treating their hosts as little better than performing monkeys in a zoo enclosure, and expecting them to put up with behaviour they would never have contemplated at home. But perhaps nobody put it better than Monty Python’s Eric Idle in 1972, with his violent rant about the hordes of tourists ‘carted around in buses surrounded by sweaty mindless oafs from Kettering and Coventry in their cloth caps and their cardigans and their transistor radios and their Sunday Mirrors, complaining about the tea.’ ‘Yes, yes,’ agrees Michael Palin’s travel agent, hoping to shut him up. But it is no good: from his nightmarish vision of the ‘party from Rhyl’ who cannot stop singing ‘Torremolinos, Torremolinos’ to his horrified memory of the ‘drunken greengrocer from Luton’ with last Tuesday’s Daily Express and firm views on Enoch Powell, Idle is only just warming up. And who could blame him?15

The most common bone of contention, though, was the food. As Idle’s disgruntled tourist notes, the first item on many supposedly ‘international’ hotel menus often bore a disturbing resemblance to warmed-over Campbell’s Cream of Mushroom soup. In fairness, many tourists were glad of anything that reminded them of home, recoiling in horror from the supposedly greasy, garlic-infested local fare. Accounts of the early days of package holidays teem with stories of holidaymakers gagging at the sight of pasta, noodles or grilled fish, manfully trying to eat spaghetti with a knife and fork, or even marching into the kitchens and ordering the local cooks to prepare them a traditional British meal, which no doubt won them plenty of friends in the Mediterranean catering trade. When Hunter Davies accompanied Tottenham’s footballers on a trip to Nantes in November 1971, he wryly observed their horror as they were served steaks with little daubs of garlic butter. ‘They all said they hated garlic,’ he noted, and ‘they tore at it furiously, swearing, and wiped all marks of it from their steak’.16

Within just a few years, however, even working-class tastes were changing. By 1975, Newcastle United’s Malcolm MacDonald was telling Shoot that he liked ‘all types of food … Indian, Italian, Greek or plain old English’. By now there were already thousands of Indian takeaways from Scotland to Cornwall, thanks to the flood of Commonwealth migrants in the 1950s and early 1960s, while in 1976 the number of Chinese takeaways officially overtook that of fish and chip shops, with kebab shops not far behind. Then there were the theatrical Italian trattorias with their ‘low-slung lighting, strings of empty Chianti bottles, bread-sticks in tumblers, and conically folded napkins of unearthly whiteness and rigidity’, as one writer put it in 1974, or the Greek and Cypriot tavernas that sprang up during the political turmoil of the early 1970s which drove thousands of refugees to London. Increasingly, too, foreign foods were finding their way into the ordinary British household, from beef goulash and lamb moussaka to coq au vin and chilli con carne. ‘Why should you wait for a dinner party to enjoy them?’ asked adverts for Brie and Camembert in 1978. Even the laziest cooks had the opportunity to experiment, thanks to Vesta’s mouth-watering ‘Package Tour’ ready meals. From Italy came Beef Risotto (‘the real taste of the Continent’); from India came Curry and Rice with Chicken (‘Pineapple, apples and sultanas, coriander and cumin make this delicious curry’); and from China, with added political correctness, came Chow Mein with Crispy Noodles (‘You like, yes?’).17

The other obvious European innovation was wine, hitherto a treat reserved for the rich and famous, or perhaps for special occasions, but now an essential ingredient of even a modest suburban dinner party. Tottenham’s players might hate garlic, but their manager Bill Nicholson liked his wine; Davies noted that his taste for Sauternes was ‘the only sliver of middle-class life which appears to have rubbed off on him’. When Nicholson had been growing up in the 1920s, one of nine children in a working-class Yorkshire family, a taste for wine would have been condemned as sissified French pretentiousness. As late as 1950, only 5 per cent of the population drank wine once a week or more, 36 per cent drank it on special occasions only, and 59 per cent said they never touched it at all. But tastes were changing. In 1960, the British drank 3.6 pints of wine per head per year; by 1971 they drank 7 pints, by 1973 9 pints, by 1975 11 pints and by 1980 almost 20 pints. One obvious reason was that it was cheaper than ever, with the duty having been slashed when Britain joined the EEC; another was that people picked up the taste on holiday; a third was that wines were advertised more successfully, being associated with glamour, luxury and ambition, and aimed particularly at young women. As The Times’s wine critic Pamela Vandyke Pryce pointed out in 1973, there was still a long way to go, given the keenness for chilling wines to ‘iced lolly texture’, filling glasses to the absolute brim or knocking back vast amounts of Blue Nun, Black Tower and Mateus Rosé. ‘You’ll like this, sir,’ a wine waiter tells a diner in one memorable Private Eye cartoon. ‘It’ll make you very drunk.’ Still, although later generations poured scorn on the wine-drinkers of the 1970s – Alan Partridge, for example, is a big fan of Blue Nun – the point is not that British tastes were inherently terrible but that they were simply untutored, since the great majority had only started drinking wine within the last twenty years. But then as Basil Fawlty so rightly observes, it is ‘always a pleasure to find someone who appreciates the boudoir of the grape. I’m afraid most of the people we get in here don’t know a Bordeaux from a claret.’18

The government formally opened talks with the members of the EEC in Brussels at the end of October 1970. Originally, the head of the team had been Anthony Barber, but when he was promoted to Chancellor, his place was taken by the much more colourful Geoffrey Rippon, who had a quick mind, a healthy impatience with details, a fondness for large cigars and – unusually for the time – a telephone installed in his car, much to the amazement of his officials. As on previous occasions, the talks were mind-numbingly boring to all but the most dedicated Euro-enthusiast, with endless haggling over New Zealand cheese and butter, Caribbean sugar, the Community tariff, and economic issues such as sterling’s role as a world currency. Tedious as they might seem, however, these were hardly unimportant issues: the Common Fisheries Policy, for example, proved a bitter bone of contention for years afterwards, with British trawlermen complaining that they had been done out of a living by the government’s surrender to European interests.

At the time, the Labour Party protested furiously that Heath had caved in to his Continental chums, and in later years Heath’s name was mud among Conservative Euro-sceptics, who blamed him for Britain’s excessive contribution to the EEC budget (later partly recovered by Mrs Thatcher) and the abomination of the Common Agricultural Policy, a gigantic subsidy scheme for inefficient, obstreperous French farmers. But the brutal truth is that the British were hardly in a position to dictate their own terms. If they had entered the Common Market in the 1950s, as the Europeans had urged, then they would have had a much bigger say in its rules and conventions, so the Common Agricultural Policy might never have got off the ground. But by 1970 it was too late; as the chief civil servant in the negotiating team, Sir Con O’Neill, later noted, the British were faced with a staggering 13,000 typewritten pages of European enactments, all reflecting compromises between the existing members, and they were hardly likely to make friends by demanding that all these issues be reopened. The only solution, O’Neill said, was to ‘swallow the lot, and swallow it now’, which inevitably meant bad bargains on dairy products, fishing rights and the EEC budget. That was the price Britain paid for having stayed aloof for so long; the choice was not between bad terms and good terms, but between bad terms and nothing.19

Whatever the outcome of the negotiations, it would all be for nothing if the French again vetoed Britain’s application. From the very beginning, Heath knew that he had to succeed where Macmillan and Wilson had failed, persuading the French that Britain was genuinely committed to the cause of European unity, and was not merely a stalking horse for American influence. ‘It was to the French that we should pay attention,’ Douglas Hurd wrote later, summarizing his master’s views. ‘We must gain friends in France and outmanoeuvre our enemies.’ This was easier said than done, of course. Fortunately, General de Gaulle, Britain’s chief antagonist in the past, was off the scene, having died suddenly in November 1970. His successor, Georges Pompidou, was a shrewd banker with rural origins and pragmatic instincts, not a nationalistic showman like de Gaulle. Even so, Pompidou was not necessarily sympathetic to Britain’s application; indeed, he harboured a deep suspicion of Harold Wilson, dating from an unfortunate incident in 1967 when Wilson had turned up late and dishevelled for an official dinner because he had been at a Commons debate on Vietnam – a moment, Pompidou thought, that spoke volumes about Wilson’s subservience to American interests. But as luck would have it, Heath was already a good friend of Pompidou’s private secretary Michel Jobert, whom he had first met, bizarrely, on a beach in Spain in 1960. Rather implausibly, Heath had gone to Spain to try to lose weight, and was lying on the beach one day when Jobert came across and murmured: ‘If you don’t eat any more, you’ll never be able to deal with de Gaulle.’ The diet was forgotten; the two men called for sherry and prawns, and a close friendship was born. A few years later, when Heath gave a series of lectures on European integration, he made sure to send them to Jobert. ‘Pompidou knows that you are serious,’ the Frenchman reported back a few weeks later.20

In May 1971, Heath and Pompidou were due to meet for the first time in Paris, and Heath prepared as though he were a schoolboy facing an exam that would decide his entire future. ‘For hours on end the Prime Minister sat under a tree, dunking biscuits in tea,’ Douglas Hurd remembered. ‘Experts were produced individually and in groups … They each had their session under the tree, while ducks from the park waddled amorously across the lawn, and over the wall on the Horse Guards workmen banged together the stands for the Queen’s Birthday Parade.’ It was clear, however, that mood music was more important than mastery of detail: what mattered was to persuade Pompidou that the British were ready to become good Europeans. Interviewed on Panorama a few days before the summit, Pompidou explained that the ‘crux of the matter is that there is a European conception or idea’, and ‘the question to be ascertained is whether the United Kingdom’s conception is indeed European’. He even mischievously told a French newspaper that Britain must agree that French was the main language of the EEC, because English was the language of the United States. But Pompidou had not taken into account Heath’s capacity for linguistic vandalism, for when Broadstairs’ favourite son recorded a message to be shown on French television, the results were truly excruciating. The next day, when Heath arrived at Orly airport and said a few words in French for the cameras, the welcoming party had to stifle snorts of derision. Heath might consider himself a good European, but never had the language of Voltaire and Flaubert been so cruelly abused.21

Fortunately, Pompidou was in a forgiving mood, and when the two men met at last on 20 May, the talks were a triumph. Leaving their officials behind, Heath and Pompidou decided to thrash out the issues on their own, accompanied only by their interpreters. They ‘clicked’, Con O’Neill recalled later. ‘They liked each other and they trusted each other.’ Outside, their advisers waited nervously, anxious that their masters were merely exchanging amiable pleasantries without getting down to brass tacks. But they need not have worried. At the lavish banquet at the Elysée Palace that night, wrote one reporter, the room ‘glowed with the warmth and satisfaction of an estrangement ended and a friendship regained’. Pompidou’s remarks at the dinner were notably generous – ‘Through two men who are talking to each other, two peoples are trying to find each other again’ – and the next morning’s talks continued in similar vein. Indeed, they went so well that, instead of calling a press conference immediately after lunch, Pompidou suggested they keep talking. It meant that Heath would have to miss an important race in his beloved Morning Cloud, but in the interests of Britain’s European future, he thought it was worth it.

At last, at nine that evening, the two men emerged for a press conference in the splendid gilded Salon des Fêtes, the very room in which de Gaulle had announced his devastating veto in 1963. By now the waiting pressmen were convinced that something had gone badly wrong, and even Heath’s senior advisers were pale with nerves since – in typical style – their boss had decided to tease them by saying nothing and looking as miserable as possible. Their surprise was therefore all the greater when Pompidou broke the good news. ‘Many people believed that Great Britain was not and did not wish to become European, and that Britain wanted to enter the Community only so as to destroy it or to divert it from its objectives,’ he said. ‘Many people also thought that France was ready to use every pretext to place in the end a fresh veto on Britain’s entry. Well, ladies and gentlemen, you see before you tonight two men who are convinced of the contrary.’ Even Heath could not suppress a broad smile at that. ‘It was marvellous to see the looks of astonishment on the faces of so many of those present,’ he later wrote. ‘We had secured success and also triumphed over the media. For me personally, it was a wildly exciting moment. Just forty years after my first visit to Paris, I had been able to play a part in bringing about the unity of Europe.’22

With Pompidou’s blessing, the British team now found the waters a lot smoother. The French negotiators adjusted their positions overnight, deals were reached on everything from New Zealand butter to the sterling balances abroad, and at the end of June Geoffrey Rippon returned in triumph from Luxembourg, ‘wearing a red tie and with a scarlet handkerchief sprouting jauntily from his jacket pocket’, reported The Times, as though he had picked up a dash of Continental flamboyance. Even Heath’s men privately admitted that the terms were not perfect, but to have got them at all was a great achievement, and there seemed every chance that Britain could press for changes in the years to come. Meanwhile, Heath wasted little time in parading his accomplishment before the British people. On 7 July, the government issued a White Paper setting out the terms, accompanied by a glossy 16-page brochure on the case for British membership. ‘Either we choose to enter the Community and join in building a strong Europe on the foundations which the Six have laid,’ said the White Paper, ‘or we choose to stand aside from this great enterprise and seek to maintain our interests from the narrow – and narrowing – base we have known in recent years.’ And on television that night, Heath was in typically sweeping but banal form. ‘For twenty-five years we’ve been looking for something to get us going again,’ he told the nation. ‘Now here it is. We must recognize it for what it is. We have the chance of new greatness. Now we must take it.’23

What was conspicuously lacking from Heath’s case for joining the EEC was any admission that it might affect Britain’s national sovereignty and self-government. In his broadcast to the nation, he talked in terms of renewing Britain’s prestige, explaining that joining the EEC would be ‘a chance to lead, not to follow’, allowing Britain to ‘fulfil the role we have played so often in the past’. As his biographer remarks, one of the paradoxes of Heath’s European vision was that it was rooted in ‘sturdy English patriotism’, with the Prime Minister convinced that Europe was the ideal platform on which to display Britain’s inherent greatness. But it made no concession to the argument that, by joining the EEC, Britain would be giving away its national sovereignty. In his fine history of Britain in Europe, Hugo Young suggests that sovereignty did not seem a key priority in the early 1970s, with economic issues apparently much more important. But not only did maverick Euro-sceptics like Enoch Powell, Michael Foot and Tony Benn make great play of Heath’s alleged surrender of sovereignty and the European threat to the sanctity of Parliament, but the thirty-nine Tories who ultimately voted against the bid often cited sovereignty as their central concern. Rather than meet their arguments head on, Heath preferred to sweep them under the carpet. His White Paper claimed that there was no question of ‘any erosion of essential national sovereignty’ but instead proposed ‘a sharing and an enlargement of individual national sovereignty in the general interest’, which was so vague as to be practically meaningless. Meanwhile, Heath’s ministers deliberately avoided admitting that European Community laws would take precedence over British law, even though they knew perfectly well that this was the case.

This does not mean, however, that the British people were duped by a sinister federalist conspiracy. Rather, as one historian writes, they were ‘told what they wanted to hear’, becoming partners in a ‘compact between a disingenuous governing class and a people too preoccupied with the economic problems of the day to pick a fight over a constitutional issue which even the most politically astute knew would not begin to affect their lives for many years to come’. From Heath’s point of view, this was not deception so much as careful political strategy – something all too rare during his time in office. ‘If Heath had laid it on the line, what he thought it would lead to,’ Denis Healey said later, ‘he wouldn’t have got it through. He thought it was more important to get it through, even if it was ignorant and misunderstanding acquiescence rather than support, than to let it go. And I suspect he was right about that.’24

Since Harold Wilson had been looking forward to taking Britain into Europe himself, the spectacle of Heath and Pompidou exchanging smiles like love-struck teenagers must have been deeply infuriating. As grammar school and Oxford boys from modest backgrounds, as dynamic modernizers fascinated by the machinery of government, the two rivals had a lot in common. For years Wilson had held the upper hand; during the late 1960s he had dismissed Heath’s clumsy attacks in the Commons with almost embarrassing ease. All that had changed, however, in a few hours in June 1970. Once the cheeky, cheerful prodigy of British politics, the former Boy Scout had taken defeat very badly indeed. It was a ‘terrible trauma’ for him, one aide said, while others remarked that Wilson seemed exhausted, demoralized, even burned out, a careworn and untidy figure who relied on handouts from his very shady business friends just to keep his office going. It was revealing that when the BBC’s David Dimbleby asked about his finances for the controversial documentary Yesterday’s Men in 1971, Wilson kicked up an enormous fuss with the BBC governors. In the old days, when he was younger, fitter and quicker-witted, he would simply have come up with a smart reply. And even in the Commons, where he had once carried all before him, he seemed tired and apathetic, his speeches perfunctory when they had once been dazzling. As Anthony Sampson reported in 1971, he seemed shrunken, diminished, ‘mesmerised by his memory’, forever harking back to the past when once his eyes had been firmly fixed on the future.25

In some ways this made Wilson the ideal leader for a miserable, backward-looking party. The Labour Party was a deeply unhappy ship in the early 1970s, defeat having cast it into yet another debilitating bout of feuding and factionalism. Its problems ran deep: after the humiliating devaluation of the pound, Wilson’s approval rating had sunk to unprecedented depths, while the party had been crushed in one local election after another, losing control of cities like Sheffield and Sunderland, as well as all but four of London’s thirty-two boroughs. Beyond that, however, lay a deeper problem. As the party’s industrial heartlands were transformed by economic change and social mobility, so its core vote entered a steady decline. Even in the late 1950s, political experts had wondered whether Labour could ever hold its own in an increasingly affluent society, but Wilson’s invocation of science and modernization had temporarily papered over the cracks. Now, in defeat, there was a palpable sense of horizons narrowing as Labour turned inwards, relying more and more on the council tenants of the North, Scotland and Wales, on public-sector workers and on the trade unions. Paradoxically, its parliamentary representatives were increasingly well-educated and middle-class, their politics driven by conscience rather than class. In 1966, the Labour benches contained more university graduates than the Tory ones for the first time, and by October 1974 no fewer than 182 Labour MPs had university degrees.26

Revealingly, they included 22 journalists, 25 university lecturers, 32 barristers and 38 schoolteachers, but only 19 miners – a far cry from the first Labour representatives at the dawn of the century. And many of the newcomers burned with righteous anger, impatient to see injustice banished by a genuine social revolution. For Wilson they had only contempt; increasingly, they looked for inspiration to the messianic figure of Tony Benn. Once the former Viscount Stansgate had been Wilson’s semi-comic technological protégé, safely confined to redesigning stamps and opening the Post Office Tower. But with Labour in the wilderness, Benn took the opportunity to reinvent himself as a latter-day Puritan demagogue, the heir to the Levellers and champion of participatory democracy, workers’ control and massive nationalization. Many of his colleagues openly scoffed at his ostentatious gestures of proletarian solidarity, such as when he formally asked the BBC to stop calling him Anthony Wedgwood Benn, or when he deleted all references to his expensive education from Who’s Who. But mocking Benn was now a risky business: nobody had more support among the high-minded young activists who increasingly dominated Labour’s constituency parties.27

Even without the issue of Europe, Labour would have slid into bickering and factionalism after 1970. Wilson’s government had been disfigured by almost unbelievably self-serving disloyalty from his senior ministers, who seemed to spend more time plotting against their leader than actually doing their jobs, while Wilson made matters worse by trying to play his ‘crown princes’ off against one another. And once he had lost his image as a winner, he also lost his ability to restrain their mutual dislike. By 1971 the party seemed to be subsiding into indiscipline, with senior figures trying to outdo one another by moving ever further to the left. Looking around that year’s Labour Party conference, one journalist wrote that he could almost see in the rows of faces ‘the layers of political geology’ as the rock face crumbled, from the ‘pacifists with their bright eyes and violent convictions’ to the ‘small bands of Marxists’, from the ‘cranky fringe parties handing out angry pamphlets in the foyer’ to the ‘Oxford intellectuals’ who still believed they ought to be running the show. It was no wonder that, even then, political commentators wondered whether the party could survive without a major split. In January 1974 Wilson’s former Commonwealth Secretary George Thomson, now one of Britain’s two European Commissioners, told a friend that even if Labour won the next election ‘the internal strains would be so great as more or less to paralyse it’. If Labour lost, he mused presciently, ‘he thought it would split, giving rise to a new Social Democratic Party’. He was a few years too early; but he was right all the same.28

It was around Europe that the fault lines developed. Labour had always had its fair share of European enthusiasts, most of them members of the liberal coterie that had gathered around Hugh Gaitskell in the late 1950s and early 1960s (even though Gaitskell himself was passionately anti-European). To them, the cause of Europe had an almost religious intensity: it was the cause, they thought, of tolerance, of progressivism, of liberalism, of cosmopolitanism, and their high priest was a man who embodied all of these characteristics, or at least tried to, the former Chancellor Roy Jenkins. But they were never more than a minority, and their generally moderate politics (regarded as right-wing by Labour standards) automatically made them targets of suspicion. ‘The pro-Market fanatics’, said the firebrand Barbara Castle, were ‘sanctimonious middle-class hypocrites’, and plenty of her colleagues agreed with her. There was a long tradition of Little England insularity inside the Labour Party, an introverted desire to build socialism in one country, a Methodist suspicion for the corrupt Catholic ways of the wine-drenched Continent, which might appeal to Tories but could never compete with an honest pint of workers’ ale (or in Tony Benn’s case, a gallon of tea).

By the early 1970s, this had evolved into the firm belief that the Common Market was a millionaires’ conspiracy, designed to crush British socialism for ever. This was, after all, an age in which there was no dirtier word in the socialist lexicon than ‘multinational’, with companies being excoriated not just because they were pillars of capitalism but because they were owned by foreigners. The EEC was therefore the perfect target – not least because it was so close to the despised Heath’s heart. It was a ‘rich nations’ club’, Michael Foot told the voters of Ebbw Vale, opposed to ‘the interests of British democracy [and] the health of our economy’. It would destroy ‘the real power of the people to control their destiny’, agreed Neil Kinnock – this, of course, some years before he became a European Commissioner himself. ‘Beating capitalism in one country is enough of a task. Beating it in several countries – without even having a solid domestic base – goes too far even for me.’29

It was in the unmistakably English surroundings of Blackpool, at the Labour conference in October 1970, that Wilson first realized he had a serious problem on his hands. In theory at least, he could ignore the fact that the conference had come dangerously close to endorsing outright opposition to EEC entry. But he could not ignore what happened in January 1971, when more than a hundred of his own MPs signed an early day motion opposing EEC entry ‘on terms so far envisaged’, or in May, when Jim Callaghan gave a blistering speech warning that British membership of the Common Market would mean a ‘complete rupture of our identity’ and a retreat into ‘continental claustrophobia’. In a memorably chauvinist passage, Callaghan poured justified contempt on Pompidou’s suggestion that French should be the sole language of Europe. That ‘the language of Chaucer, Shakespeare and Milton must in future be regarded as an American import’, Callaghan said mockingly, was totally unacceptable. ‘If we are to prove our Europeanism by accepting that French is the dominant language of the Community, then the answer is quite clear and I will say it in French to prevent any misunderstanding: Non, merci beaucoup.’30

This was good knockabout stuff, but for Wilson it was deeply disturbing. Although he and Callaghan got on fairly well, they had been undeclared rivals since the early 1960s, and the popular former Home Secretary was seen as embodying the solid centre of the party, the darling of the trade unions, the ‘keeper of the cloth cap’. By his very presence he seemed to define the centre ground; where he went, scores of Labour MPs followed. And since Wilson could never shake the suspicion that Callaghan was plotting a coup against him, he decided to step in before his rival laid claim to the anti-European mantle. ‘He is totally obsessed by the leadership question now,’ noted Tony Benn after they met to discuss Europe in June. ‘The risk that Jim Callaghan might stand against him is something that worries him very much.’

Never mind that Wilson himself had once been all for EEC membership; as he had shown before, nobody in British politics was a better or more unscrupulous adept of the dark arts of party one-upmanship. So, after months of hedging and waiting and vague ambiguities, he chose the occasion of the party’s Special Conference on the Common Market, held in Westminster on 17 July, to nail his colours to the mast. With typical Wilson cleverness, he did not come out against the principle of Europe, only the practice. The problem, he said, was the terms: ‘I reject the assertion that the terms this Conservative Government have obtained are the terms the Labour Government asked for, would have asked for, would have been bound to accept.’ Nobody believed him, but that was almost beside the point. ‘It’s all over bar the shouting now,’ wrote Benn, ‘and he feels he has warded off Jim Callaghan’s assault on the leadership, which he almost certainly has.’31

But that was far from the end of the matter. Labour’s pro-European wing – the ‘Marketeers’, as they were known – were horrified by Wilson’s apparent treachery, especially since it confirmed what many of them had suspected for years: that he was a duplicitous, untrustworthy political fixer, unfit to wear the mantle of their beloved Hugh Gaitskell. Above all, Wilson’s most dangerous rival, Roy Jenkins, was outraged at his perfidy. Jenkins himself was not exactly the soul of self-denying constancy: even while serving as Wilson’s Chancellor in the late 1960s, he had maintained a network of personal supporters in the Commons, and on more than one occasion came close to launching a leadership putsch. In June, he had even tried to strike a deal with Wilson, promising that if the leader stayed true to the European cause, then ‘there could be no question of the Labour Europeans joining in any intrigue with Callaghan or anyone else to embarrass him, still less to endeavour to replace him’. But this, of course, was little less than blackmail: if Wilson had accepted, he would not only have alienated much of the left and centre of his own party, he would have made himself a prisoner of the Jenkins camp, his leadership dependent on his European enthusiasm. Fortunately for him, his principles were endlessly flexible, so he was able to wriggle out of it. But Jenkins’s principles were not. He already cut a slightly semi-detached figure in the Labour Party of the early 1970s, a sleek and self-consciously sophisticated lover of croquet, tennis, fine wines and aristocratic women. ‘With his big smooth head he looks like an aristocratic egghead,’ one profile remarked in 1971, calling him ‘the most improbable leader of a workers’ party’. Even then, observers commented that he seemed ‘more like a Liberal than a Labour leader’, more at home with the memory of Asquith, whose biography he had written, than with the modern reality of Arthur Scargill. And as Jenkins saw it, Europe left no room for compromise. It was ‘a battle between outward-looking tolerance and generosity of spirit on the one hand’, wrote his friend David Marquand, ‘and mean-minded Pecksniffian narrowness on the other’.32

Jenkins issued his declaration of war just two days after Wilson had come out against the terms of the EEC bid. At a raucous meeting of the Parliamentary Labour Party, he insisted that ‘socialism in one country’ (or ‘pull up the drawbridge and revolutionise the fortress’, as he witheringly put it) was ‘not a policy, just a slogan’. The atmosphere sizzled with revivalist passion; Jenkins later wrote that the speech attracted more ‘violent applause’ than any other of his career, with many Labour MPs hammering their desks in approval and one Scotsman even banging his shoes on the table, as if in homage to Khrushchev. On the left, however, the reaction was horror and disgust. In the Commons smoking room afterwards, left-wing Euro-sceptics huddled in angry conclaves, and as Jenkins passed, Barbara Castle, no stranger to hysterical over-reaction, said bitterly: ‘Roy, I used to respect you a great deal, but I will never do so again as long as I live.’ As for Wilson, he characteristically saw the issue purely in terms of his own leadership, not in terms of Britain’s long-term future in Europe. The next morning, Tony Benn found him ‘extremely agitated’, issuing wild threats against Jenkins and talking of walking away from the party leadership, but underneath all the bluster ‘desperately insecure and unhappy’. All in all, it was a pretty pathetic spectacle of introversion and feuding, played out in the full gaze of the media and the public. And with Jenkins adamant that Britain’s European future must come before party unity, there seemed little prospect of an end to hostilities. ‘I saw it in the context of the first Reform Bill, the repeal of the Corn Laws, Gladstone’s Home Rule Bills, the Lloyd George Budget and the Parliament Bill, the Munich Agreement and the May 1940 votes,’ Jenkins wrote later.33

What finally pushed Jenkins overboard was a wheeze that Benn himself had cooked up at the end of 1970, which was for the next Labour government to call a national referendum on the issue of Europe. At first, Wilson rejected the idea outright; at the time, only Callaghan realized that it offered the ideal way to paper over Labour’s European divisions, remarking sagely: ‘Tony may be launching a little rubber life-raft which we will all be glad of in a year’s time.’ But by the beginning of 1972 Wilson had come round. Although a referendum would be unprecedented, it was the perfect way of appeasing the sceptics without completely conceding the issue. Jenkins, however, loathed the idea of referendums, not least because this most self-consciously elitist of politicians saw them as ‘the likely enemy of progressive causes from the abolition of capital punishment to race relations legislation’. When the Shadow Cabinet voted to back the scheme in March 1972, Jenkins demanded the right to speak against the decision, and when this was denied, he promptly resigned as deputy leader. ‘It was the only way he could see to lance a swelling boil of misery and guilt,’ his friend David Marquand wrote later, and Jenkins’s letter seethed with righteous anger, denouncing Wilson’s ‘relentless and short-sighted search for tactical advantage’. In the process, however, he comprehensively demolished his last chance of becoming Labour leader. Like the last deputy leader to resign, George Brown, he made no secret of his bitter contempt for Wilson’s endless compromises, but his bombshell was no more effective than Brown’s. Although Jenkins still commanded the ardent support of a small group of right-wing admirers, his reputation within the broader Labour Party, where loyalty and solidarity were still seen as the supreme virtues, was in ruins. A Harris poll in October found that 79 per cent of Labour supporters preferred Wilson, with a pitiful 5 per cent picking Jenkins. A few days later the party conference formally approved the referendum scheme, and the twin issues of Europe and the leadership had been settled at last.34

Roy Hattersley wrote later that the day Jenkins resigned was the moment ‘the old Labour coalition began to collapse’. In the light of what happened later, it did indeed look like a dress rehearsal for the launch of the SDP, with two other members of the Shadow Cabinet, George Thomson and Harold Lever, resigning in sympathy and Bill Rodgers, David Owen, Dickson Mabon and Dick Taverne all leaving their junior shadow positions. Even in the short term, it did tremendous damage to Wilson’s reputation. As the Telegraph’s Colin Welch wryly remarked, the gulf between the public images of Jenkins and Wilson was enormous: on the one hand ‘an almost saintly figure, heroic, shining, guided only by honour and high principles, even to the sacrifice of his own career’; on the other, ‘a dark serpentine crawling trimmer, shifty and shuffling, devious, untrustworthy, constant only in the pursuit of self-preservation and narrow party advantage’. Wilson himself found this deeply infuriating: during a Shadow Cabinet meeting, he once snapped: ‘I’ve been wading in shit for three months to allow others to indulge their conscience.’ By now, however, there was not much he could do about it; trapped into a position of wriggling ambiguity, he had become for many observers the incarnation of everything that was wrong with British politics in the 1970s: its narrowness, its short-termism, its petty positioning, its navel-gazing introversion. On the Labour right, he was regarded with something like repugnance; even on the left, he was seen as merely the best of a bad bunch. He was ‘the principal apostle of cynicism, the unwitting evangelist of disillusion’, declared an extraordinary leader in the New Statesman in June 1972. ‘We say it with reluctance but we believe it to be true. Mr Wilson has now sunk to a position where his very presence in Labour’s Leadership pollutes the atmosphere of politics.’35

This was strong stuff, though not entirely baseless. It might well have been better for all concerned if Wilson had retired after 1970, bequeathing the leadership to the tougher, more reassuring Callaghan; certainly his historical reputation would be much higher if he had. And yet there was something to be said for his undeniably slippery tactics during the European debate. At a time when Labour might easily have torn itself apart, Wilson at least managed to hold the party together. Even Denis Healey, who generally held his leader in very low esteem, thought that he showed ‘great courage in refusing absolutely to reject British entry in principle’. Whereas Callaghan would probably have demanded a stance of outright opposition, and Jenkins would have split the party by declaring wholehearted support, Wilson’s implausible complaints about ‘the terms’ actually kept the principle of European membership alive. What this meant is that when Labour returned to office, it was committed to holding a referendum rather than automatically taking Britain out of Europe. Wilson may have looked like a weasel, but in the long term, his approach worked: Labour stayed together, and Britain stayed in Europe. It was sheer ‘duplicity’, writes the pro-European Hugo Young, but it was ‘nonetheless one of Wilson’s finer hours’. Of course, Britain’s European destiny was above all Edward Heath’s achievement. But his great rival perhaps deserves a share of the credit – or the blame.36

While Labour’s senior figures were busy tearing into one another with the brutal relish of First Division footballers on a muddy Saturday afternoon, the Prime Minister had already turned his thoughts to the battle for public opinion. In May 1970, he had made the vague but ringing promise that Britain would enter the EEC only with the ‘full-hearted consent’ of its Parliament and people. But with just one in five voters backing European membership at the time of the election, winning public consent would clearly take some doing. Even after negotiations had begun, Gallup found that one in three people thought their standard of living would decline if Britain joined the EEC, while fully 73 per cent thought that their food bills would rise ‘a lot’. Even in April 1971, just before Heath’s historic summit with Georges Pompidou, nearly 70 per cent of the public said they opposed British membership, most citing rising prices as their biggest concern. But although the economic dimension was clearly the most important, many people did have reasons that were more cultural, almost spiritual, for resisting European entry. Asked in July whether they would lose their British identity if the country went into the Common Market, 27 per cent thought ‘a lot’ and 62 per cent ‘some’. If Heath wanted to win them over, his adviser Michael Wolff told him, his appeal must not only address the prices issue, but should be ‘based on high ideals and national destiny and should be particularly aimed at youth’.37

Heath’s answer was the biggest state publicity campaign since the war, with a Cabinet committee coordinating a vast range of nationwide talks and events, including almost 300 public speeches by government ministers. Not even holidaymakers were safe: on beaches across the country, families basking in the summer sun were accosted by girls in tight T-shirts with the logo ‘SAY YES TO EUROPE!’, who were handing out copies of a free newspaper called the British European. Inside, graphs showed Europe’s faster growth rate and the great welter of economic benefits that would come Britain’s way, while national icons such as Kenneth More and Bobby Moore assured readers that they were all for European cooperation. But the message was not all food bills and productivity charts: ‘EUROPE IS FUN!’ screamed the cover, next to a photograph of a Page Three lovely in a skimpy Union Jack bikini. ‘More Work But More Play Too!’ Needless to say, this kind of stuff drew widespread derision: in the Commons, one Labour MP mockingly charged that Heath’s ministers were ‘as frenetic in their enthusiasm to convert public opinion as the Chinese Christian who decided to baptise his troops with a hosepipe’. But they were undeterred: even the government’s White Paper on the terms for entry was recruited into the campaign, with no fewer than 5 million copies distributed in Post Offices as a 16-page booklet with a fetching green and black cover. It was a telling sign of public indifference, though, that the reaction was ‘muted enthusiasm and often perceptible lack of interest’. In Trafalgar Square’s Post Office, which had the longest counter in Britain, the booklets were piled almost to the ceiling, but they were ‘barely touched’ by customers. ‘Most people are rather bored by it all,’ explained a middle-aged housewife. ‘They are sure we are going in anyway.’38

In the press, the mood was overwhelmingly pro-European. Both The Times and the Guardian were extremely keen from the very beginning, as were the Sunday Times, the Observer and The Economist, while the Telegraph, reflecting its loyalty to Heath, moved off the fence and into a position of unquestioning support, telling its readers that when MPs finally came to decide the question, ‘they will be passing a judgement on a civilisation, a culture, an economic union, a nascent defence capability, above all an idea of Europe that cannot be rejected without grievous results for Europe’s future and our own’. The Mail had been wavering since the early 1960s, but as soon as Wilson and the trade unions declared their opposition, it announced it was strongly in favour. So was the Sun, which boasted that it had been in favour of EEC membership for its entire lifetime, while the bestselling Mirror ran a stream of fiercely pro-European pieces. ‘Are a people who for centuries were the makers of history – and who can again help to make history – to become mere lookers-on from an off-shore island of dwindling significance?’ demanded a ferocious editorial in July 1971. Even its lighter pieces often had a pro-Market slant: there was even a ‘Guide to the Euro-Dollies’, reporting on how they rated as kissers. Only the Express stood ‘alone – with the people’, as it put it, warning that the talks had been ‘a victory won by French diplomacy over British interests’. It was therefore delighted when Prince Philip, making one of his trademark public interventions, waded into the debate to attack the Common Agricultural Policy. ‘The people admire his good sense,’ said the Express, ‘and wish it were more widely shared by our rulers.’ But its competitors were less impressed. The Prince was a ‘chump’, said the Mirror, while the Sun thought it was high time ‘our sailor Prime Minister told the sailor Prince which way the wind blows’.39

In cultural circles, too, the mood was strongly pro-European. When the magazine Encounter organized a symposium of writers and intellectuals in the summer of 1971, forty-six respondents were in favour and only seventeen against. Still, the sceptics were joined by such impressive names as Anthony Burgess, who claimed that ‘England is to be absorbed, her own distinctive character sordined, and the end of a great Empire to be completed in the bastardisation of a great empire-building nation’, while Kenneth Tynan told The Times that the EEC was ‘the most blatant historical vulgarity since the Thousand Year Reich’. It was a ‘capitalist bloc’, Tynan wrote in his diary, sounding ‘the deathknell of socialism in Western Europe’, although the fact that these thoughts followed a long anecdote about Britt Ekland’s knickers rather deflated the impression of progressive commitment. But not all theatrical diarists of the day were sceptics, for Kenneth Williams sent Heath a letter in May 1971 ‘saying I admire him very much; do hope he gets us into Europe’. And even Doctor Who came out in favour of the Common Market. A week after Heath had signed the Treaty of Accession in January 1972, the Doctor and his companion Jo arrived on the planet Peladon, which had just applied to join the Galactic Federation, much to the displeasure of its High Priest and presumably the Peladonian equivalents of James Callaghan, Kenneth Tynan and the Daily Express. The High Priest insists that the Federation will ‘exploit us for our minerals, enslave us with their machines, corrupt us with their technology’, but he is eventually unmasked as a double-dealing blackguard. Meanwhile Jon Pertwee’s Doctor, like some infinitely more dashing Ted Heath, convinces Peladon’s King that only Federation membership can bring the modernization his people need. But the Doctor has to come to terms with his own prejudices, too; for among the members of the Federation are the once-terrifying Ice Warriors, now reformed. At first these towering Martian reptiles seem certain to prove the villains of the piece – but once they have saved the Doctor’s life, it becomes clear that they are simply Doctor Who’s answer to Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt.40

Not surprisingly, public opinion began to shift under this barrage of commentary. What is clear from the polls is that most people did not really know what to think about the EEC, and did not care much either way. Public support ebbed and flowed with bewildering speed: just a year after 70 per cent of the public had proclaimed themselves against, polls in July 1971 showed the pro and anti camps dead level – but then a few months later the pro camp had collapsed again and the opponents were 12 per cent ahead. Conservative supporters naturally rallied to Heath, and local constituencies reported overwhelming support by the end of 1971, but there was no sense of a ‘Great Debate’. The historian A. J. P. Taylor grandly claimed that it was ‘the most decisive moment in British history since the Norman Conquest or the loss of America’, but most people were content to follow the advice of their favourite politicians or columnists rather than dig out the White Paper and decide for themselves. Perhaps the best reflection of public opinion was the experience of the Conservative official who was sent to Liverpool on a mission to gauge local attitudes to Europe. On arrival, he stopped a woman in the street and asked what she thought of the Common Market. ‘Where are they building it, love?’ she asked.41

Once the terms had been agreed, Heath’s central priority was to get the appropriate legislation through the House of Commons. This was trickier than it looked, since there were bound to be Tory rebels, and he might need to rely on support from the Labour right. Of all his parliamentary critics, by far the most persistent, elegant and passionate was his implacable adversary Enoch Powell, once a keen supporter of the Common Market, but now the fiercest of sceptics. As early as February 1970, Powell had warned that entry into the EEC would mean absorption ‘economically, legally, commercially and politically’ into a European super-state. And as Heath’s negotiations neared their goal, Powell’s warnings became ever more apocalyptic. If Britain signed the Treaty of Rome, he told the Commons in January 1971, it would ‘lead to an irreversible alienation of our separate sovereignty’. He denied that Britain even had a basic European identity: her place had always been with her back to Europe ‘and her face towards the oceans and the continents of the world’. The battle in the Commons, he said, was a ‘life and death struggle for its independence and supreme authority’, a struggle ‘as surely about the future of Britain’s nationhood as were the combats which raged in the skies over southern England in the autumn of 1940. The gladiators are few; their weapons are but words; and yet their fight is everyman’s.’42

If Powell had merely been a lone maverick, then Heath would have had nothing to worry about. The problem, though, was that at least thirty Conservative MPs, most on the right of the party, shared his views and were expected to vote against the government when it came to the crunch. By the middle of October 1971 the moment of truth was at hand, with the House being asked to give its approval of the government’s decision to join the EEC, and the atmosphere crackled with tension, every day bringing fresh reports of ‘nose-counting, arm-twisting, weak knees and stiff upper lips’. If Heath had had his way, the government would have ploughed unswervingly onwards, demanding the loyalty of its supporters, and might well have crashed to defeat. But he was lucky to have in Francis Pym an outstandingly clear-sighted Chief Whip, who managed to persuade him – after weeks of trying – that it would be better to allow a free vote on the grounds that he wanted a true reflection of the will of the House, rather than a vote on purely partisan lines. That way, Pym argued, they might lose a few more Tory votes, but they would be able to pick up far more Labour rebels, who would be much happier to defy their party leadership if they were not technically voting with the government. As Heath himself admitted, it was only through ‘Pym’s wise instinct’ that he eventually secured a majority in perhaps the single most important Commons vote of the late twentieth century.43