The stink of the blacks made him sick. He hated spades – wished they’d wash more often or get the hell back where they came from. This was his London – not somewhere for London Transport’s African troops to live.

– Richard Allen, Skinhead (1970)

AGGRO BRITAIN: ‘Mindless Violence’ of the Bully Boys Worries Top Policeman

– Daily Mirror, 14 June 1973

By the beginning of the 1970s, the British Empire had been consigned to history. As one colonial possession after another had declared independence during the 1950s and 1960s, so the swathes of imperial pink that had once covered maps in classrooms across the country had vanished. When Edward Heath flew to Singapore for the first Commonwealth Conference in January 1971, it was as the chief executive of a rusting industrial conglomerate, once a market leader but left now with just a handful of tiny, scattered subsidiaries: Hong Kong, the Seychelles, St Vincent, the Falkland Islands. Heath could not even console himself that Britain had left a noble legacy, for the record of the newly independent countries, from the permanent tension between India and Pakistan to the civil war in Nigeria, from the ethnic bloodletting in Cyprus to the reactionary defiance of Rhodesia, made for shameful reading. Only two years before, Kenya had become a one-party state, while Uganda’s President Milton Obote, once a hero of the struggle for independence, now ruled as a virtual dictator, imprisoning and torturing anyone who dared criticize him. And what was even worse from a British point of view was that the new post-colonial leaders seemed to have no respect for their old imperial masters, no sense of obligation or community. For when Heath arrived in Singapore, it was to an atmosphere of bitterness and recrimination, with African leaders queuing up to denounce his policy of selling arms to South Africa in return for the use of the Simonstown naval base. And when he faced his severest critics – Zambia’s Kenneth Kaunda, Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere and Uganda’s Obote – he found it hard to keep his patience. ‘I wonder how many of you’, he finally snapped, ‘will be allowed to return to your own countries after this conference?’1

At the time it sounded like a typical example of Heath’s absurd rudeness. In fact, it turned out to be a remarkably accurate prediction, for a week later Milton Obote was on his way home from Singapore when the news broke that he had been toppled by a military coup. After Obote’s flagrant corruption, his intolerance of dissent and his threats to British commercial interests in Uganda, his replacement seemed like a breath of fresh air. All political prisoners, announced Major General Idi Amin, would soon be released, while he hoped to hold ‘free and fair’ civilian elections as soon as possible. And since General Amin had a reputation of being pro-British, noted The Times, his rise to power was greeted ‘with ill-concealed relief in Whitehall’. As a young man he had not only been the Ugandan light heavyweight boxing champion, he had been a warrant officer in the King’s African Rifles, holding the highest rank possible for a black African, and in 1961 had been one of the first two Ugandans given a Queen’s Commission. He had even learned to play rugby, being selected as a reserve forward for the East Africa XV to face the touring British Lions in 1955. The story goes that his Scottish officers used to hit him on the head with a hammer to inspire him before big games: perhaps that explains why he rarely seemed the sharpest of intellects. ‘Idi Amin is a splendid type and a good player,’ one officer reported, ‘but virtually bone from the neck up, and needs things explained in words of one letter.’ By January 1971, however, that was precisely what Uganda needed – or so most British observers thought. Amin was ‘not a man of intellect or political finesse’, admitted the Guardian, ‘but [one] with great ability at man-to-man straight talking with ordinary soldiers’. He would be ‘a welcome contrast to other African leaders and a staunch friend to Britain’, announced the Telegraph. ‘Good luck to General Amin.’2

It did not take long for the Telegraph to realize its mistake. Within months of the coup, it was clear that Amin had no intention of surrendering power to a civilian administration, and clear too that beneath the blustering, jovial exterior was a thoroughly aggressive, cunning and unscrupulous political operator. To Punch’s columnist Alan Coren, who regularly parodied Amin’s clumsy ignorance, his grandiose pretensions and his thick African accent, he seemed merely a ‘buffoon’. But the Ugandans imprisoned and murdered under his increasingly paranoid regime were not laughing. And neither were the 60,000 Asians – most of them originally from Gujarat in India – who had come to Uganda during the days of the British Empire, working as clerical staff, bankers and tailors.

Racial tensions had been growing since Ugandan independence, exacerbated by the fact that the Asians were generally well educated, affluent and socially exclusive, keeping themselves apart from their black African neighbours. ‘We were the visible middle class,’ recalled the columnist Yasmin Alibhai-Brown. ‘We didn’t much care for independence when it came in 1962, and we did what was necessary – bribes, public demonstrations of support for this minister or that – anything that could keep us living enchanted lives in a natural paradise.’ Between the two communities was a thick wall of racial tension: when she played Juliet in a school production alongside a black African Romeo, her own father refused to speak to her for three years. And even before Amin took power, the temperature was rising. Among the Asians, rumours spread that Africans were raping their daughters; among the black Ugandans, there were stories that the ‘greedy’ Asians were hogging all the best jobs, were sending money overseas, were ‘cheating, conspiring and plotting’ to undermine the state. They were the easiest of targets; too easy for Idi Amin to resist. ‘I want the economy to be in the hands of Ugandan citizens, especially black Ugandans,’ he told a military assembly on 4 August 1972. Since the Asians were ‘sabotaging the economy of the country’, all those with British passports should pack their bags. They had ninety days to leave.3

For Heath and his ministers, Amin’s bombshell left them facing a terrible dilemma. On the one hand, they recognized that Britain had a moral obligation to accept the Asians, not merely because they faced persecution and expulsion, but because an estimated 57,000 of them held British passports. As the Foreign Secretary, Sir Alec Douglas-Home, reminded his colleagues four days after Amin’s announcement, ‘we could not disclaim responsibility for British passport holders even if we so wished’; in any case, the impact on Britain’s reputation overseas would be catastrophic. But public opinion within Britain was a very different matter. Like most of his ministers, Heath had always been determinedly moderate on questions of race and immigration; indeed, his dogged refusal to play the race card and his decision to sack Enoch Powell for rocking the boat on immigration had upset many grass-roots Tories in the last years of the 1960s. But his position in the election campaign of 1970 had been clear. Public opinion overwhelmingly demanded an end to mass immigration, so an end must be made. In October 1971, therefore, the government had passed a landmark Immigration Act bringing up the drawbridge. From now on, only so-called Commonwealth ‘patrials’ with a parent or grandparent born in the United Kingdom (which meant they were likely to be white) had the right to settle in Britain; all other Commonwealth citizens had to apply for work permits, just like everybody else. Some observers detected a hint of racism in the distinction between ‘patrials’ and the rest; indeed, Reginald Maudling told his colleagues that since assimilation was ‘all but impossible’ for Asians, immigration ought to be limited to people from a ‘cultural background fairly akin to our own’. But Heath’s ministers were, by and large, a liberal-minded lot, and certainly far more tolerant than the majority of the population. They closed the door to mass immigration not because they were racist reactionaries, but because public opinion – as manifested in one poll after another – demanded it. The Act worked and the furore died down – until Idi Amin reignited it.4

At first, even as terrified Ugandan Asians were desperately calling friends and relatives in Britain to beg for help, the government tried to play for time. On 12 August, Heath sent his urbane European troubleshooter, Geoffrey Rippon, to Kampala to persuade Amin to change his mind or, at the very least, to extend his deadline. Unfortunately the former rugby forward made it clear that he would not yield an inch of ground. ‘I have already made up my mind. Finished!’ Amin melodramatically told the press corps. ‘This is British imperialism. I am not going to listen to imperialist advice that we should continue to have foreigners controlling the economy.’ What was more, once Rippon had gone home, the Ugandan president increased the stakes by withdrawing his promised exemption for selected Asian professionals. ‘They could not serve the country with a good spirit after the departure of other Asians,’ he explained. And with Amin standing firm, the British government had no real choice. ‘We will accept our responsibilities,’ Rippon announced. ‘If people are expelled and they are United Kingdom passport holders, then however unreasonable that expulsion may be, and however inhumane and unjust the conditions in which it is brought about, we have to accept the responsibility … I don’t think anyone in a situation like this can stand aside and say, “Oh, it’s no concern of ours.” ’ Other senior Conservatives took a similar view. It was a question of ‘honour and decency’, said Reginald Maudling, now exiled to the back benches. ‘If homes elsewhere in the world cannot be found for them,’ agreed Sir Alec Douglas-Home, ‘we must take these unlucky people in.’5

Since the Labour leadership agreed that Heath had no choice but to accept the refugees, the Ugandan crisis never became a partisan issue. Almost all senior politicians, in fact, agreed with The Times that even though Britain had recently accepted immigrants ‘at a faster rate than most similar communities would find tolerable … the ultimate responsibility for British citizens lies with Britain’. But it was an academic anthropologist, Nicholas David, who put it best in a letter to the paper the next day. The Ugandan Asians, he pointed out, were ‘our colonial legacy’, and it was the Conservative government of Harold Macmillan that had given them their British passports. To discriminate between different colours of passport holders would be to follow the examples of Nazi Germany and South Africa. ‘These islands are indeed overpopulated, reason enough to discourage all immigration,’ he concluded, ‘but unless we are to forsake what we say we stand for, we cannot refuse entry to fellow subjects of the Queen who have no other country of their own.’

And yet Dr David, like the editor of The Times and like Heath himself, was in the minority. In the tabloids there was talk of a ‘deluge’ of immigrants, a ‘flood’ of newcomers that would put Britain on ‘panic stations’. In cities with already large Asian populations, which were bound to attract considerable numbers of refugees, there were howls of protest from local councillors. ‘We are virtually full up,’ insisted the Labour leader of Leicester City Council, encouraging residents to send letters of complaint to the government. By early September, the council had even taken out an advertisement in the Uganda Argus imploring Asians not to come to Leicester, while Bolton Council collected thousands of signatures to a petition demanding that they stay out of Bolton, too. And day after day, letters pages burned with the fury of correspondents worried that their country was about to be overrun, their homes, jobs and opportunities threatened by tens of thousands of foreigners who, through a fluke of history, happened to have British passports. ‘I have every sympathy with these unfortunate Asians, some of whom I have counted as friends for many years,’ wrote the former Conservative MP Sir John Fletcher-Cooke (whose friends must have been hastily revising their social diaries). ‘But both they and the British Government failed to realize that peoples of one culture or background will never willingly share power, political or economic, with those of another culture.’ And for another Times reader, Katherine Fussell, who called herself ‘an ordinary British subject and housewife’, the question was one of ‘hard everyday facts’:

The Clydeside shipyard workers have fought extremely hard for their daily bread, the dockers are in a struggle for theirs, the transport workers are wondering what will happen to some of their jobs, at the Norwich shoe factory women staged a stop-in to save theirs. Not all these fights are successful in these times of much unemployment.

Mines have been shut down, and we hear of men in all walks of life offered redundancies in place of their work. White and black citizens of this country cannot buy or rent a house easily. Many young folk cannot get married because of the housing problem or if they do they live with in-laws and many marriages fail. Young school leavers, white and black, are on the streets with nothing to think about or do, they draw the dole! The future is bleak indeed.

This situation should not be aggravated by a large influx from any country. These people if allowed in must be housed, fed and found work. Schools must be found to take the children. If they are given national assistance they will strain the economy already at breaking point … Let the Government make it clear to these people from any country wanting to come to us, that the immigration quota remains and they must wait their turn when they will be more than welcome.6

For some people, however, the Ugandan Asian crisis was a godsend. For the right-wing Monday Club, which had been set up to oppose decolonization in the 1960s, it was an opportunity to attract new supporters and stoke up opposition to Heath within the Conservative Party. As early as 7 August it had issued a statement insisting that the ‘so-called British Asians are no more and no less British than any Indian in the bazaars of Bombay’. They had ‘no connexion with Britain either by blood or residence’, explained the Buckinghamshire South MP Ronald Bell, and should ‘go back to their own country’, meaning India (a country that had already ruled out accepting large numbers). And although there was no chance that the Tory leadership would take a blind bit of notice of the Monday Club’s pronouncements, its members could console themselves that Britain’s best-known politician agreed with them. ‘All the talk of “British passports” is spoof,’ Enoch Powell told a Conservative lunch in Wolverhampton on 14 August. The passports, he explained with his characteristically fierce logic, gave no ‘entitlement to enter this country’ and implied ‘no connexion with the United Kingdom itself’, and while the government might feel morally obliged to accept an ‘infinitesimal’ share of the refugees, it had no obligation to take them all.7

As the crisis wore on, so Powell’s rhetoric became more strident. ‘In order to govern a people and to lead them, you must enter into their feelings and their fears, and they must know you enter into them,’ he told a Round Table audience a few weeks later. And yet ‘at this moment hundreds of thousands of our fellow citizens here in Britain are living in perpetual dread: they dread for themselves, or they fear for the future, or they dread for both’. He singled out the elderly, ‘who live in actual physical fear’, as well as those who feared for their children, ‘who feel as if they are trapped or tied to a stake in the face of an advancing tide’. But ‘beyond all these, and including all these’, Powell said, ‘are those who watch an alteration, profound and irrevocable, which they feel powerless to arrest or to protect against, engulfing the places, the towns, the cities which they knew and which they thought were theirs’. And if Heath’s government would not address their fears, then ‘another must’.8

By 1972, Powell was comfortably the most popular politician in the country, voted ‘Man of the Year’ in a BBC poll two years running. Once the youngest professor in the British Empire and the youngest brigadier in the British Army, the MP for Wolverhampton South West now cut a brooding, isolated figure, a prophet to his admirers, a pariah to his enemies. In full flow in the House of Commons he often seemed icily logical, pressing his argument to its conclusion without regard for the sensibilities of his audience. In fact, he was a man of smouldering passions, from Housman and Nietzsche to High Anglicanism and hunting. As a newspaper profile had put it when he ran against Heath and Maudling for the Tory leadership back in 1965, he had ‘the taut, pale face of a missionary, and the zealous energy of a man who is not afraid of the stake’. Ever since his extraordinarily divisive ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech (a phrase he never actually used) in 1968, he had been in the political wilderness, and had not even spoken to Heath since his dismissal from the Shadow Cabinet. Yet while his doom-laden predictions ensured him the hatred of students and the liberal left, they had also made him enormously popular with the general public; indeed, three out of four people told pollsters they agreed with him. His appeal crossed regional and party boundaries: he was regarded as a courageous, independent man, the tribune of the voiceless masses. And the more that student demonstrators tried to drown him out, the more his support seemed to grow. During the general election campaign of 1970, Tony Benn had histrionically claimed that ‘the flag hoisted at Wolverhampton is beginning to look like the one that fluttered over Dachau and Belsen’. Two weeks later Powell almost doubled his majority, and afterwards some analysts suggested that he had attracted as many as 2 million working-class voters to the Conservative Party. He had tapped into a widespread feeling, wrote the Guardian’s Peter Jenkins, that ‘the politicians are conspiring against the people, that the country is led by men who had no idea about what interests or frightens the ordinary people in the backstreets of Wolverhampton’.9

Then as now, Powell’s views and career were widely misunderstood. Often caricatured as a fire-breathing reactionary, he actually held remarkably liberal views on many social issues. Not only did he vote for the legalization of homosexuality and the abolition of hanging, but his most celebrated parliamentary speech was a withering attack on British atrocities in the Hola detention camp in Kenya, which even Labour observers thought was one of the most moving Commons speeches they had ever heard. And although he loathed the project of European union and regarded the United States with deep distaste, it is hard to see a man who taught himself French, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Hebrew, Italian, Russian and Urdu as a xenophobic Little Englander. Set against all that, however, is the fact that in April 1968 Powell gave a speech that thousands of immigrants found deeply unsettling, even terrifying; a speech that repeated some of the racist urban myths of the day in terms that were bound to prove inflammatory; a speech that horrified even some of his oldest and closest friends. And whatever the nuances of Powell’s own position, which was often much more complicated than his critics allowed, there is little doubt that genuine racists drew comfort from his stand. From Wolverhampton, which had virtually no history of racial antagonism before the speech, there came reports of white youths attacking immigrants and chanting ‘Powell, Powell’. And according to the National Front’s organizer in Huddersfield, his speeches ‘gave our membership and morale a tremendous boost. Before Powell spoke, we were getting only cranks and perverts. After his speeches we started to attract, in a secret sort of way, the right-wing members of the Tory organizations.’10

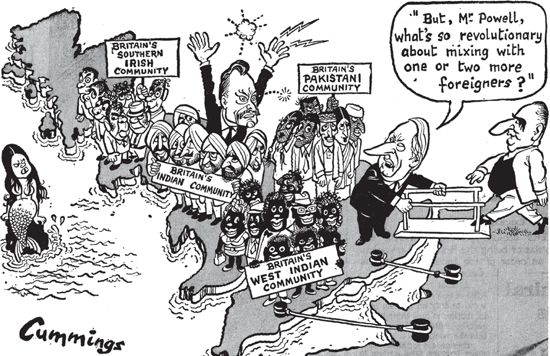

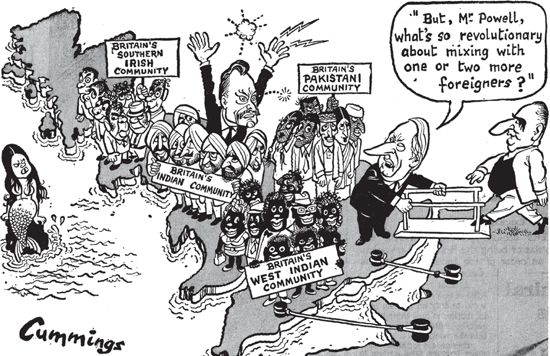

With his trademark moustache and blazing eyes, Enoch Powell was a gift to the cartoonists, and in this image for the Daily Express (10 April 1972) Cummings links him with immigration, the EEC and Northern Ireland. It is easy to be shocked by the racial caricatures, but it has to be said that Bernadette Devlin makes a fine mermaid.

The irony, though, is that even as Powell’s speech effectively destroyed his political career, it made his name as a national icon. As far as the general public were concerned, all the complexities of Powell’s career, from his liberal attitudes to homosexuality and hanging to his radical free-market economic ideas, were reduced to just one issue: race. To those frightened by immigration or alienated from the political system, he became an overnight hero. ‘He’s the finest man in the country,’ one elderly Blackburn woman told Jeremy Seabrook, prompting a chorus of approval: ‘He should be Prime Minister.’ ‘He started too late with all this black business. He should have started sooner.’ ‘He speaks the mind of all the white – well, three quarters of the white people in this country.’ ‘I think Enoch is a marvellous man, and I hope that some day he’s Prime Minister.’ ‘He’s whiter than white is Enoch. Whiter than white.’ In popular culture, meanwhile, support for Powell was used everywhere from episodes of Coronation Street to spin-off novels from The Sweeney to identify resentful, racist or reactionary working-class characters. ‘Enoch’s Dreaming of a White Christmas’, sings Albert Steptoe in one Steptoe and Son Christmas special, while Alf Garnett is never slow to invoke the sage of Wolverhampton. ‘It’s a pity old Enoch ain’t in charge,’ he mutters in an episode of Till Death Us Do Part from January 1974, while behind him, to the hilarity of the audience, a black electrician arrives to fix his broken television. ‘He’d sort them out. He’d put the coons down the pits, he would.’11

As opinion rallied against the Ugandan Asians, it was Powell’s name that protesters invoked to justify their opposition. When 400 Smithfield meat porters, joined by groups of dockers and porters from Covent Garden, marched on Westminster on 24 August, they carried placards reading ‘ENOCH WAS RIGHT’. Two weeks later they organized a second march, this time to the headquarters of the TGWU, again carrying banners proclaiming their determination to keep ‘BRITAIN FOR THE BRITISH’. But while the Smithfield porters had seized national attention four years before, marching on the House of Commons in an unsuccessful attempt to have Powell restored to the Shadow Cabinet, there was an unexpected twist this time. Just days after the second march, Granada’s World in Action team recruited one of the more vehement anti-immigration porters, Wally Murrell, to travel to Uganda and interview people on all sides of the crisis. Murrell was in Kampala for only three days before Amin kicked him out, yet on his return he confessed that he had changed his mind. ‘I must admit that when I saw what one Asian family had to give up to leave the country it influenced me,’ he said. ‘What impressed me while I was there was the violence that was only just beneath the surface. I was convinced that there would be a bloodbath if they stayed.’ Many of his fellow porters were horrified by his apostasy: when he appeared on World in Action to retract his opposition, he was bombarded with obscene phone calls. ‘He does not speak for us,’ one porter angrily told the press. But others were more supportive. ‘All morning blokes came up to me individually,’ Wally said after his first day back at Smithfield, ‘and said they respected what I had done and admired me for speaking out.’12

Wally Murrell was not, of course, the only person whose compassion for the Ugandan Asians trumped his concern that Britain was becoming overcrowded. In Leicester, leaders of the Asian community raised £10,000 to provide for the expected influx of refugees, took over 200 houses due for demolition and even prepared to set up temporary classrooms for the refugees’ children, staffed by teachers who had previously run schools in Uganda. ‘We must not put all the burden on the British Government or people,’ explained H. S. Ratoo, chairman of the British Asian Welfare Committee. ‘We must take the responsibility and make preparations to help the people.’ But it was not only Asians who went out of their way to welcome the exiles. By the middle of September, the government’s Ugandan Resettlement Board was reporting that 2,000 people had written to offer rooms in their own homes, and by the end of the month a further 3,000 had followed suit. In the Isle of Wight, stereotypically a conservative part of the country with virtually no black or Asian residents, a Ventnor hotelier offered to put 90 Asians up at his hotel, while Fred Sage offered to house 500 refugees at his Bay View Holiday Park in Gurnard. Another proprietor, Bertram Wrate, even offered to put up 100 refugees in his nudist camp at Blackgang. And all the time, despite the torrent of criticism in the tabloid press, clothes, blankets and supplies poured in. ‘We know many of you didn’t really want to leave your homes and jobs in Uganda,’ The Economist assured the refugees.

You know we didn’t really want you to come here, because we have problems with homes and jobs here. But most of us believe that this is a country that can use your skills and energies … You will find that we, like other countries, have our bullies and misfits. We are particularly sorry about those of our politicians who are trying to use your troubles for their own ends. And we’re glad your British passport means something again.13

In an ideal world, Heath and his ministers would have liked the Ugandan Asians to disappear somewhere else: to India, perhaps, or to Canada, which agreed to take several thousand. There was clearly no chance that Idi Amin would change his mind: he was ‘fundamentally irrational and unreliable’, Robert Carr, the Home Secretary, wrote in early August. As an emollient and strikingly liberal man, popular on both sides of the House, Carr had not been an obvious Tory candidate to run the Home Office; indeed, in a period of high public anxiety about law and order, it might have been better for Heath if he had chosen a more authoritarian figure. But from the refugees’ point of view, Carr was the perfect Home Secretary, persuading his Cabinet colleagues to approve £750 per family towards their travel expenses as well as subsidies for local authorities faced with mass arrivals. He was no fool: whenever the Cabinet discussed the issue, the threat of a popular anti-Asian backlash was never far from their minds, and Carr conceded that they should not give the refugees so many benefits that they lost all public sympathy. By and large, however, his handling of the crisis was a rare model of compassion and competence, although it was also made a lot easier by the fact that fewer Asians arrived than had been predicted.14

By the middle of September, it was clear that only about 25,000 refugees were coming to Britain, with others going to Canada, Australia or elsewhere in Africa. The Resettlement Board was working well, Carr reported on 21 September; local authorities were dealing smoothly with the inflow; and above all ‘the public now seemed disposed to accept the [Asians] as genuine refugees’. At the party conference a few weeks later, Carr even recorded a notable rhetorical triumph, swatting aside Enoch Powell’s attempt to humiliate the leadership over immigration and securing a two-to-one mandate for the government’s approach. If they had abandoned the Ugandan Asians, Heath reminded a Tory audience at the end of November, ‘they would be rotting in concentration camps prepared by President Amin, and they would be there simply because of the colour of their skin and the fact that they held British passports. That would have been the sight presented to us on our television screens night after night this Christmas. I cannot believe that anyone in this country would have regarded such an outcome as acceptable.’15

All in all, the Ugandan crisis brought the best out of Edward Heath. A few years earlier, Harold Wilson had rushed through an emergency bill to stop the mass influx of Kenyan Asian refugees. But even though Heath’s government was under even greater pressure over immigration, he never wavered in his view that Britain had a moral obligation to its passport holders in their hour of need. For once his mulish obstinacy shone through as courageous commitment: the more that right-wing critics slammed his refusal to follow public opinion, the more he seemed determined to honour Britain’s moral and legal obligations. Not surprisingly, representatives of Britain’s Asian community were full of admiration. Heath’s policy, said Praful Patel of the All-Party Committee on United Kingdom Citizenship, was ‘in the highest traditions of justice and fair play so often shown by the British people. The decision to accept responsibility for these people is a tremendous credit for the Government. It vindicates our trust in them.’ And there were moving words from a group of Indian students who wrote to The Times at the beginning of September:

Some of us have been in your country and as young Indians we have come to love and respect Britain. We have experienced the welcome and hospitality in your homes. We have been struck by the concern your people have for other nations … We have been inspired by the British Government’s readiness to accept the Uganda Asians with British passports at a time when the country faces unemployment, crisis in industry and in Northern Ireland.

Your Government has shown true statesmanship in honouring past promises and in fighting for humane treatment to be given to these men, women and children. This adherence to moral responsibility by British leaders is encouraging when expediency and national interest decide policies the world over.

For a group of foreigners – especially from a former imperial possession – to write of their admiration for British politics in the early 1970s was rare indeed. On this occasion, though, Heath deserved it.16

At the beginning of the 1970s, perhaps a million Caribbean, Indian and Pakistani immigrants and their children lived in Britain.* Although there were pockets of black and brown life right across the nation, immigrant communities tended to be concentrated in heavily urbanized areas, especially where there had once been plenty of low-paid jobs and cheap housing. More than half of the immigrant population lived in London and the South-east, and a further 16 per cent lived in Birmingham, Wolverhampton and the industrial towns of the West Midlands, with smaller clusters in Lancashire, West Yorkshire and the East Midlands. The biggest group were the Indians, who accounted for about 30 per cent of the total, and who had already made a deep impression on British cultural life through their restaurants, of which there were perhaps 2,000 in 1970, serving cheap, anglicized curries to young couples and late-night revellers. Then came the West Indians, who accounted for 25 per cent and were overwhelmingly concentrated in London and Birmingham. In 1971, the official census recorded a Caribbean population of 170,000 in the capital alone, which was surely an underestimate. The third biggest group, at 13 per cent of the total, consisted of Pakistani families, often from poor rural village backgrounds. Many settled further north in the textile towns of Yorkshire and Lancashire, which in the 1950s and 1960s had a thirsty demand for cheap unskilled labour: in Bradford, there were about 50,000 Pakistani residents by the early 1980s.17

These were not, of course, the only immigrant communities in Edward Heath’s Britain. By the late 1960s, there were already around 75,000 Greek and Turkish Cypriots in London alone, having fled the political unrest in their native land. After the Turkish invasion in 1974, about 10,000 more followed, most of them Turks settling in the north-east of the capital, where they opened innumerable restaurants, bars and community centres. And then there were the Hong Kong Chinese, easily Britain’s quietest and least assimilated major immigrant group – so quiet, in fact, that even racist campaigners sometimes forgot they were there. The 1971 census put the Chinese population at 96,000, almost all of them working in the catering trade. By this point, Chinese restaurants were even more popular and numerous than Indian ones. In many areas, their willingness to work long hours meant that they virtually supplanted (and often physically took over) the old fish-and-chip shops, and by the early 1970s virtually every sizeable town had developed a taste for chow mein and sweet and sour sauce. Yet even though the Chinese population almost doubled during the 1970s, there was no repeat of the racist panics of the Edwardian era, and no talk of the yellow peril. For one thing, they were widely dispersed across the country; for another, they worked such long hours and were so discreet that they were rarely even noticed. Ironically, although critics often complained that immigrants did not even try to fit in, the ones who provoked least hostility were those who made least effort to do so.18

Ever since mass immigration from the Commonwealth began in the early 1950s, successive governments had been anxious to make sure that the newcomers found productive work and a chance to make their way up the ladder. Initially there seemed good reason for optimism: a study in 1970 found that many immigrants had readily adapted to new challenges, with 18 per cent of both Indians and West Africans finding professional or technical work and another 19 per cent getting clerical jobs. But by the mid-1970s it was worryingly obvious that progress had stalled. One problem was that thousands of immigrants had chosen to live in industrial towns with falling populations and cheap housing – precisely those places, in other words, that suffered most in the economic troubles of the 1970s. And since the mills and factories that would once have given newcomers a foothold on the ladder were closing down, they often found themselves condemned to low-paid manual jobs in dreary, dilapidated, depressed towns that the rest of Britain had forgotten. By 1975, government figures showed that unemployment among immigrants was twice the national average, while young black school-leavers were four times less likely than their white counterparts to find jobs. Education was not always the answer: a year later, more figures suggested that one in four West Indian and Asian university graduates now worked in manual trades, compared with only a tiny proportion of white graduates. And by the beginning of the 1980s, it was clear that the decline of Britain’s manufacturing industries had taken a heavy toll on the ambitions of its immigrant population. In 1984, eight out of ten Caribbean men and seven out of ten Asian men were still working as manual labourers – compared with only five out of ten whites. And instead of moving up the property ladder, immigrants found themselves trapped at the bottom: in London, for example, some of the most run-down, violent and intimidating housing estates virtually became immigrant reservations, such as the Holly Street Estate, Hackney, or Broadwater Farm, Haringey. Here too racial discrimination clearly played its part, but to an extent the newcomers were simply the helpless victims of economic history.19

Outside London the situation was little better. Nottingham, for example, had attracted a sizeable immigrant population in the 1950s and 1960s thanks to its history as a major textile town. By 1971, Commonwealth immigrants accounted for about 6 per cent of its total population, and a council official estimated that there were 10,000 West Indians, 4,000 Indians and 3,000 Pakistanis. Instead of being dispersed across the city, they were packed into a few seedy, neglected inner-city neighbourhoods such as St Ann’s, Lenton and Radford. But this was not merely a matter of choice. Despite the race relations legislation of the late 1960s, housing discrimination was still a fact of life: in February 1971 Nottingham’s Fair Housing Group, which had close links to the council, local estate agents and building societies, reported that ‘discrimination still continues to appear in various forms when an immigrant intends to purchase a house in one of the suburban areas of the city’. It was ‘so subtle’, the report claimed, ‘that even the Race Relations Act has become powerless to prevent it’.

In interviews, immigrants consistently complained that white residents refused to sell to them, that neighbours put pressure on sellers to pull out, that building societies were reluctant to give them mortgages or would ask for an impossibly high deposit. In Nottingham, seven out of ten said that they had suffered housing discrimination, while almost eight out of ten complained of employment discrimination too. Time and again, they said, they were turned down without an interview, or told that the job had been filled as soon as the interviewer discovered they were black. One man rejected for a salesman’s job, for example, was told that ‘customers might not like a coloured man calling on them’, even though the interviewers admitted that he was perfectly ‘fit for the job’. So it was hardly surprising that no fewer than nine out of ten West Indians told researchers that they had been deeply disappointed by the realities of British prejudice. ‘We thought England was the home of justice – so we got quite a shock,’ one said. ‘The least little trouble they’ll turn round suddenly and say why don’t you go back where you come from,’ another lamented. ‘I was not expecting at all any prejudice or discrimination,’ admitted a third. ‘As a matter of fact I did not know I was a coloured man until the English tell me. Somebody referred to me as a coloured person on the bus once and that was the first time I knew who I was.’20

That many people were prejudiced is not in doubt. In the same survey, six out of ten white Nottingham residents agreed that ‘English’ people should have priority in council housing. ‘It’s our bloody country so we should get first chance,’ one said. ‘Because the English fought to keep out the invaders and all both governments have done since is to open the doors to them all,’ said another. ‘We’ve fought two wars to keep our country English so we should have priority,’ insisted a third. And an even greater proportion (67 per cent) agreed that the ‘English’ ought to have priority in employment, too, even though this was technically illegal under the Race Relations Act of 1968. ‘It’s our country. I know some blacks are born here but I still think the Englishmen should have priority,’ one said. ‘It’s England isn’t it? I’m Alf Garnett. He said that when God made this earth he allotted a little bit to everybody. I’ve got no intention of going to India,’ said another. ‘I’m not prejudiced,’ said a third. ‘It’s just an Englishman’s right.’21

Although Nottingham was badly affected by the economic downturn of the 1970s, other towns were even harder hit, and there prejudice took on a sharper, more aggressive edge. In Blackburn, Jeremy Seabrook found ‘an elaborate system of legends, myths and gossip’ surrounding the town’s 5,000 Pakistani immigrants, who made up just 5 per cent of the total population. One man told him that ‘this chap, white chap’ had heard noises in his loft one night, and upon ascending had found ‘a great long row of mattresses in the roof, all the length of the street, and on every one is a Pakistan [sic]’. Another man reported hearing that a Pakistani had managed to get £40 from the social services to pay for his car repairs (although even he admitted: ‘I shouldn’t think the Social Security’d be as generous as that’). In fact, Seabrook had heard it all before: these were common urban myths of the day, repeated in towns across the country and always involving some mysterious friend of a friend. But they were none the less virulent for being false. Visiting a Victorian terraced house in a run-down area, Seabrook met a crowd of middle-aged and elderly white women who were almost falling over each other to tell him that the Pakistanis were benefit cheats. As Seabrook saw it, the women were clearly frightened of being stranded in immigrant-dominated areas, their homes losing their value, their moral attitudes becoming obsolete in a disturbing new social and cultural landscape. The Pakistanis spat on the street, they complained; they blew their nose between their thumbs and fingers, instead of using a handkerchief; their wives did not even bother to scrub their front steps, as proper Blackburn women did. ‘We’re being driven out, no doubt about it,’ one said passionately. ‘We’re going back to the Stone Age,’ said another woman, ‘where they can just do as they like on the pavement … It’s like a jungle living here. People are very bitter. And if they can’t live like we live I think it’s time they went back.’22

As Seabrook pointed out, these kinds of resentments – which often seemed more bitter and outspoken in the 1970s than in the decades beforehand – were only partly the result of racial prejudice. He noticed that many of the Blackburn women seemed uncomfortable with their own sentiments: afterwards ‘there was a certain uneasiness in the room, a sense of shame, the shame of people who have unburdened themselves to a stranger’. They knew that racial prejudice was wrong, which is why they often insisted that they were not prejudiced themselves (‘but …’). ‘This business about colour is all wrong,’ one told him. ‘I had some Italians live next door to me, and nicer people you couldn’t wish to meet … They make me sick when they say it’s on grounds of colour. It’s not the colour at all.’ Of course this was not really true: ‘the colour’ – understood broadly as the immigrants’ attitudes, habits and values, as well as their appearance – was clearly a factor. But there was more to it than atavistic hatred, Seabrook thought: there was a sense of loss, of helplessness, of nostalgia for an idealized industrial working-class world with strict moral and social boundaries, a world that seemed to be slipping away. The women’s anger was ‘an expression of their pain and powerlessness confronted by the decay and dereliction, not only of the familiar environment, but of their own lives too’.23

In many ways, racial prejudice was becoming increasingly unacceptable in Edward Heath’s Britain. In the political arena, overt racism was largely unknown, and most politicians trod extremely carefully. For almost all ambitious politicians, fear of being attacked by the press as a ‘racialist’ was much greater than the appeal of pandering to working-class sentiments. It was revealing, for example, that even when tabloid newspapers were attacking immigration, they took care to present themselves as tolerant and open-minded, insisting that their opposition was based on economic or environmental factors rather than questions of skin colour. Even though more than eight out of ten people agreed with Enoch Powell in the spring of 1968 that immigration had gone too far, seven out of ten told a Race Relations Board survey that they regarded themselves as tolerant and would happily drink with a black man at the pub. And for the Daily Mirror, still seen as the voice of the ordinary working man, even this was not enough. ‘The immigrant population – especially the second generation immigrants – don’t want simply to be tolerated,’ an editorial thundered. ‘They are NOT economic units. They are human beings. They are citizens of this country here to build a new life for themselves and their families. It is as fellow citizens and fellow human beings that they are entitled to be accepted.’24

Fine words indeed; yet by the early 1970s, it was clear that racial prejudice was more deeply entrenched than it had seemed. This was, after all, a world in which the highly educated James Lees-Milne, a lover of the arts and driving spirit in the National Trust, saw nothing wrong in recording his horror that ‘half the inhabitants [of London] are coloured’. They were ‘aliens with alien beliefs’, he wrote in 1977, ‘and no understanding of our ways and past greatness. England to them is merely a convenience, a habitation, rather hostile, where wages are high and the State provides.’ This was tame stuff, though, compared with the views of Philip Larkin, arguably Britain’s finest poet, who complained to his mother in 1970 that ‘one child in eight born now is of immigrant parents’, and in fifty years’ time ‘it’ll be like living in bloody India’. Of course people often write controversial or politically incorrect things in their diaries or to their families and close friends. Perhaps Larkin was only joking. But it still says much that such a thoughtful and sensitive poet (albeit one with extremely conservative man-of-the-people opinions) was happy to send his friend Anthony Thwaite a Jubilee poem bemoaning ‘the rising tide of niggers’, or to tell Robert Conquest that one of his poetic tips on ‘How to Win the Next Election’ was to ‘kick out the niggers’. And it also says much that in one of the first Inspector Morse novels, Last Seen Wearing (1977), Colin Dexter’s intellectual detective, arguing with a Maltese bouncer in a strip-club, readily calls him a ‘dirty little squit’ and a ‘miserable wog’ – and that his sidekick, Sergeant Lewis, then a Welshman, clearly thinks nothing of it.25

As so often, it was humour that best revealed the limits of racial tolerance. Racist banter in the workplace, for example, was very common. ‘I went for a job up the road,’ one black 18-year-old told the Sunday Times in 1973, ‘and the man he says, “You don’t mind if we call you a black bastard or a wog or a nigger or anything because it’s entirely a joke.” ’ When the applicant answered that in that case he could ‘keep his job’, the man insisted that he was ‘not colour prejudiced’, the standard formula of the day. But it is easy to see why the employer might have thought that such ‘jokes’ were acceptable. Popular culture in the early 1970s was saturated with humour and attitudes that later generations would regard as shockingly racist. Jokes about black men and ‘Pakis’ (‘I saved a Paki from drowning the other day. I took me foot off his head’) were the common currency of pubs and working men’s clubs. In Trevor Griffiths’ play Comedians (1975), which follows the fortunes of a group of aspiring Manchester stand-up comics, almost all of them fall back on racist mockery to impress their first audience, from jokes about black physical endowment (‘a big black bugger rushes in [to the toilet]. Aaaah, he says. Just made it! I took a look, I said, There’s no chance of making one in white for me is there?’) to a particularly offensive joke about a Pakistani on a rape charge (‘They bring the girl in and the Pakistani shouts, She is the one, Officer. No doubt about it’). Yet this is one of the few jokes that make an impression on the visiting talent scout, for whom racist material is clearly nothing untoward. ‘It was a different act, the wife, blacks, Irish, women, you spread it around,’ he says admiringly to another comedian.26

What Griffiths’ play captured – and what made it controversial and deeply uncomfortable viewing when it was adapted for television four years later – was the raw, resentful tribalism of much working-class comedy in the 1970s. Even television stand-up often had a racist edge: almost no edition of ITV’s hugely popular show The Comedians, which gave a regular platform to Northern working-class comics such as Bernard Manning, Stan Boardman and Lennie Bennett, was complete without a handful of racist jokes. What was remarkable, though, was that the tellers included black comedians themselves. The South Yorkshire comedian Charlie Williams, the son of a Barbadian soldier who had settled in Barnsley, played for Doncaster Rovers in the 1950s before turning to the club circuit and was a great favourite with television audiences. As a black man with a cheerful demeanour and strong Yorkshire accent, he cut a confusingly ambiguous figure, defying easy stereotypes. Yet although Williams was a role model for a younger generation of black performers, and may well have been the most popular black Englishman in the early 1970s, his material was controversial even at the time. Among all the jokes about the minutiae of Northern working-class life – the ‘boxes of broken biscuits, terraced houses, outside lavatories, the coalface, scrumping apples’, as his obituary put it – he regularly fell back on jokes about his own colour. ‘If you don’t shut up,’ he would tell hecklers, ‘I’ll come and move next door to you.’ And while Williams sometimes poked fun at racial stereotypes – ‘When Enoch Powell said: “Go home, black man”, I said: “I’ve got a hell of a long wait for a bus to Barnsley” ’ – his act could hardly be described as particularly subversive.

More often than not, in fact, Williams simply reinforced the racist clichés of the day, delighting audiences with his remarks that he had been ‘left in the oven too long’ or was sweating so much that he was ‘leaking chocolate’. ‘During the power cuts,’ he once joked, ‘I had no trouble at all because all I had to do was roll my eyes.’ He even joked about being a cannibal, telling a story about a man he invited to dinner: ‘Halfway through the meal he says: “I don’t like your mother-in-law.” So I said: “Leave her on the side of the plate and just eat the chips and peas.” ’ This kind of material guaranteed Williams an enthusiastic reception: when he topped the bill at Scarborough in 1973, he broke box-office records. But was he merely pandering to white prejudice, or was he blazing a trail for other black comedians? He certainly inspired Lenny Henry, by far the most successful black comedian of the next generation, who admired his energy and courage in taking to the stage. Not all black observers, however, were impressed by Williams’s eagerness to do routines about ‘darkies’, ‘Pakis’ and ‘coons’. ‘He thinks he can hide behind his Yorkshire grin,’ one correspondent wrote to the Guardian, condemning Williams for not ‘speaking for his brothers’. But that was highly unrealistic: a professional comedian who performed Black Power routines would not have lasted long on ITV.27

Lenny Henry’s own career was not without its ambiguities. One of seven children born to Jamaican parents in Dudley, he made an immediate impact on the club circuit as a teenager and won ITV’s New Faces competition in 1976 when he was just 17. Almost immediately, however, he joined the touring version of the Black and White Minstrel Show, which attracted sell-out audiences almost every year in the major cities and seaside resorts. Looking back later, he admitted that there were two voices in his head: one told him that there was a ‘fundamental problem’ with appearing alongside grinning minstrels in blackface; the other told him to ‘take the money and have a great time’. In fact, it is obvious why an ambitious teenage comedian would join the Minstrels. By the mid-1970s, they had a place in the Guinness Book of Records as the world’s most popular stage show, and when Henry joined he found himself performing for twenty-two consecutive weeks at the Blackpool Opera House before 3,000 people a night. For an aspiring performer, this was an unbeatable education in cabaret and pantomime, and it made it easier for him to block out the protesters who sometimes heckled from the stalls, or the publicity photographs that showed him alongside blacked-up performers pretending to take off his make-up. Like most of the other performers, he told himself that the costumes were merely a distraction, that the essence of the show was the sets and the songs, and he accepted the conventional wisdom that it was ‘not a racial show’. Ultimately, though, he was no fool, and the protests of his friends finally changed his mind. In 1979, ‘going mad’ with frustration, he walked out. ‘The mistake wasn’t in doing the show and getting stage time and getting experience and learning to time a joke,’ he said later. It was in not realizing that, as a ‘second generation West Indian guy’, he had no place in a show based on racial caricatures.28

Defenders of the Black and White Minstrel Show often insisted that it was merely innocent, harmless fun, without any racial dimension, and that its critics were humourless killjoys. In fact the television show, which began in 1958, was dogged for much of its run by quiet murmurs of discontent within the BBC and angry protests from race relations groups. In some ways it beggars belief that neither the producers nor the performers could detect any hint of racism in routines that showed grinning men in blackface serenading pretty white women. ‘It depicts my race as singing, dancing, laughing, idiotic people,’ Clive West, a young Trinidadian who organized a petition calling for its cancellation, told The Times in 1967. But although West collected 200 signatures blaming the programme for causing ‘misunderstanding between the races’, the Minstrels refused to budge: as their producer George Inns put it, ‘how anyone can read racialism into this show is beyond me’. And in their defence, the Minstrels could point to their enormous popularity with the British public. They regularly attracted audiences of more than 12 million, drawn to the old-fashioned and highly accomplished song-and-dance routines: as late as 1976, when the show had already lost some of its lustre, the Minstrels’ Christmas special was still among the top five programmes of the season. Millions of people clearly thought the routines were perfectly acceptable, and there is no evidence that the producers were deliberately prejudiced. ‘Not one of us ever gave a thought to racism,’ the performer Les Want later told a BBC documentary. ‘We didn’t connect it with black people, because the original shows were white people blacked up. It never felt offensive.’ Yet by the mid-1970s – much to Want’s disappointment – the show had lost its supporters in the BBC. In an era when black performers like Lenny Henry and Floella Benjamin were becoming mainstays of the television schedules, not even the most conservative television executives could defend a show trading in blackface caricatures. In July 1978 it was cancelled, never to return.29

It is probably unfair to single out the Black and White Minstrel Show for special condemnation. In general, television and film culture during the 1970s was remarkably indifferent to racial sensitivities, and attempts to include black characters were often ludicrously clumsy. Superficially, Roger Moore’s debut as James Bond, Live and Let Die (1973), might look like a rare attempt to embrace black culture and promote black performers: most of the cast are black, and the producers drew inspiration from the ‘blaxploitation’ genre then popular with American audiences. In fact, the film makes even Ian Fleming’s novel look like a model of racial liberalism. While Moore has never been more effortlessly urbane, the film’s black characters, almost without exception, are villainous hoodlums, and the post-colonial black politician at its centre turns out, surprise, surprise, to be a part-time gangster and drug smuggler. ‘A white woman has been tied to a post and a black man dressed in animal skins is laughing crazily and wielding a massive poisonous snake,’ writes one Bond aficionado, reliving the experience of watching the climax as a 10-year-old in Tunbridge Wells. ‘Around them hundreds of voodoo worshippers are screaming and convulsing.’ Even when Bond appears to rescue Jane Seymour, the black revellers are ‘too busy rolling their eyes and waving old cutlasses to offer proper resistance’. And not even his pioneering sexual encounter with a black woman – who of course turns out to be a traitor and dies almost immediately – can quite dispel the impression of unthinking, endemic racism, which makes the film ‘such a shameful experience on each viewing’ – albeit a bizarrely enjoyable one.30

By this point, black faces were becoming increasingly common on British television. Crossroads introduced its first black character – Melanie Harper, played by Cleo Sylvestre – in January 1970, cleverly teasing the audience by presenting her as Meg Richardson’s daughter (although she turns out to be adopted). Four years later it became the first television soap to feature a black household – the James family, born in Jamaica – and in the summer of 1977 it presented viewers with the first interracial romance, between the Cockney mechanic Dennis Harper and the Asian receptionist Meena Chaudri. But while the producers of Crossroads handled race with rare sensitivity, others were rather less adept. Spike Milligan was a particular offender: his crude portrayal of the half-Irish half-Pakistani Kevin O’Grady (‘Paki-Paddy’) in Curry and Chips (1969) was so bad that ITV cancelled the show after just six episodes. When Milligan blacked up again with John Bird for The Melting Pot (1975), playing a Pakistani father and son who live in a London rooming house alongside a black Yorkshireman and a Chinese Cockney, the BBC pulled the plug after a single episode, afraid of a public backlash. And even the infinitely superior Rising Damp (1974–8), in which much of the comedy derives from the tension between the racist Rigsby and his black lodger Philip, is not altogether comfortable viewing today. Don Warrington’s Philip is clearly the most sympathetic character: suave, dignified and intelligent, as befits the ‘son of a chief’. Yet it is Rigsby who has all the best lines, for instance when he worries whether Philip’s behaviour will change ‘when he hears the drums’, or when he suggests that Philip’s being a chief merely means that ‘his mud hut is bigger than all the other mud huts’, or when he opines that ‘when they first had petrol stations out there, they spent three years worshipping the pumps’. As with Alf Garnett, the laughter track leaves no illusions about the audience’s sympathies. When Rigsby opens his mouth to deliver a fresh put-down, the viewers are laughing with him, not at him.31

But it was another sitcom, Thames Television’s Love Thy Neighbour (1972–6), which best illustrated the limits of racial tolerance in the early 1970s. Although later regarded as a terrible embarrassment, it was extremely popular in its day: indeed, from 1973 to 1975 it reigned as Britain’s favourite sitcom. The basic situation is very simple: a West Indian couple, Bill and Barbie Reynolds, move in next door to the white working-class Eddie and Joan Booth. The two women get on well; the two men take an immediate dislike to one another and are soon hurling insults such as ‘Choc-ice!’ and ‘Snowflake!’ over the garden fence, to the evident delight of the studio audience. Almost incredibly, when the show started there was much talk of it as a highly charged version of Till Death Us Do Part, using satire to tackle the problem of racism in modern society. Thames’s head of Light Entertainment predicted that it would ‘take some of the heat out of race relations’, while the TV Times made the extravagant claim that it was ‘about racial prejudice – with a difference. It should make us laugh a lot … and think a lot, too.’ That Love Thy Neighbour made many people think a lot, however, is very hard to believe.

As numerous academics have pointed out, the premise of the show seemed almost deliberately designed to stop audiences thinking seriously about the roots of racial tension. So the white racist, Eddie (Jack Smethurst), is shown as backward in almost every way: a Labour voter, a trade union member, a Manchester United supporter, a Daily Mirror reader, he is a relic of a dying working-class world who insists that ‘equal rights does not entitle nig-nogs to move in next door’. By contrast, the black couple are models of self-improvement and upward mobility: rather implausibly, Bill (Rudolph Walker) is a devoted admirer of Edward Heath. In other respects, though, he is just another caricatured black man, ‘a happy go lucky Jamaican with strong Conservative views’, as publicity for the inevitable spin-off film put it, with a comically childish high-pitched laugh. Meanwhile his wife, Barbie (Nina Baden-Semper), seems to be a sensible modern woman with a swanky stereo. Deep down, though, she is just another voluptuous black siren in a bikini and hot pants, who spends much of her time being ogled by white men. And throughout the series runs a thread of aggressive racial hostility that to modern eyes seems deeply distasteful. In one episode, ‘Operation Aggro’, Eddie organizes a petition to ‘Keep Maple Terrace White’ and throws dog muck over the fence, narrowly missing his black neighbour. In others, he denounces Bill to his face as a ‘coon’, a ‘bloody nig-nog’, ‘Sambo’ and ‘King Kong’, while for good measure he dismisses other immigrant groups as ‘Fu Manchu’, ‘Gunga Din’ and ‘Ali Baba’. Yet Bill himself is hardly a model of tolerance. Quick to dismiss Eddie as a ‘honky’, a ‘snowflake’ and a ‘racialist poof’, he admits to his wife that he would not want black neighbours himself because of their impact on house prices. Amazingly, though, Rudolph Walker claimed to be ‘excited’ by the scripts. ‘Here are white men writing for blacks,’ he said proudly, ‘and there isn’t a hint of the Uncle Tom.’32

Since Love Thy Neighbour attracted large audiences for eight series over four years, millions of people presumably found it hilarious. What now seems extraordinary, though, is that many critics complained that it was too tame and inoffensive. It was ‘quite bland’, said the Telegraph’s reviewer after the first two episodes, while the Observer thought it ‘all very nice and soft-centred and predictable’. In The Times, Barry Norman even commended the programme as ‘a step in the right direction’, but thought that ‘Eddie’s mild little jokes about spades and sambos and nignogs have no shock value and indeed are so gentle and so comfortable that the words themselves acquire a sort of respectability. Anyone, listening to Eddie, who has ever thought of black men as spades or nignogs might well feel reassured that this is precisely how we ought to think of them.’ As time went on and the programme lost any pretence of having a satirical edge, however, the criticism became sharper. Black viewers unsurprisingly found the programme – and especially its implied moral equivalence between the racist and his victim – deeply disturbing: in July 1975, a spokeswoman for the Race Relations Board told New Society that she had not ‘met a black person who isn’t offended to hell by it’. And as the critic Chris Dunkley pointed out in September 1972, it was ‘a little frightening that the loudest laugh from Monday’s audience, and even a little shower of applause, was elicited by a joke about a Negro’s house-warming party: the “White Honky” threatened that his house would get really warm when somebody burned it down. There seems precious little hope of cathartic benefit in cracking jokes like that.’ But as so often in the 1970s, many people simply could not understand why others were complaining. ‘Who can really take offence’, asked James Murray of the Daily Express, ‘if kids in school playgrounds nowadays copy the epithets of Eddie and Bill and call each other “Choc ice” and ‘Snowflake”? It’s got to be an improvement on “nigger”.’33

In the early hours of Tuesday, 7 April 1970, a 50-year-old kitchen porter called Tosir Ali was returning home from his work at a Wimpy Bar in central London when he ran into two white youngsters armed with knives. He bled to death at the door of his building on St Leonard’s Street, Bow, just moments from the safety of his flat. At first the police ruled out racist motives. But it soon became clear that the murder was part of a pattern of brutal attacks on Asian residents in East London, and especially on the East Pakistani* community packed into the narrow streets around Brick Lane. In one incident, two Asian workers at the London Chest Hospital were badly beaten by a gang of white youths; in another, the imam of the East London Mosque was taken to hospital after being beaten with an iron bar and kicked in the face; in a third, Pakistani mourners at the funeral parlour beside the mosque were taunted and bombarded with bottles. In what many champions of racial integration saw as a worrying development, the local Pakistani Workers’ Union announced it was organizing vigilante patrols to protect local families. But The Times sympathized with their feelings. ‘The Pakistani community in London are now badly frightened and very resentful,’ its lead editorial explained on 14 April. ‘They are coming to regret their reputation for gentleness. If nothing further is done to protect them, the time will come when they will fight back.’ It was time, the editorial concluded, for a crackdown on violence and ‘a few exemplary punishments in the courts. That was what put a stop to further violence after the Notting Hill race riots in 1958 and it may be necessary to demonstrate again with all the force of the law that young thugs will not be permitted to establish the pattern of race relations in Britain.’34

The next few weeks were a grim time for race relations. In Brick Lane, tension escalated into a full-scale race riot at the end of April; in Luton, gangs of white youths roamed the streets looking for Pakistani victims; in Wolverhampton, the Indian Workers’ Association advised its members to stay at home after dark after a string of attacks by white youngsters. And in each case, the newspapers levelled the blame at a new and uniquely disturbing figure. At one level, as the latest teenage folk devil to haunt the nightmares of Middle England, the incarnation of primeval violence and working-class rebellion, the skinhead was the descendant of the Teddy Boy and the Mod. But whereas both Teddy Boys and Mods were stereotypes of upward mobility, being working-class youngsters with unprecedented freedom, self-confidence and cash in their pockets, skinheads were defiantly backward-looking. With their cropped hair and steel-capped boots, they had originated in East London as a working-class riposte to the ‘nancy-boy’ hippies who dominated press coverage of youth culture. Skinheads were self-consciously hard; they were unapologetically working class; and above all, they were white. They hated hippies, but they hated immigrants even more. ‘We’re being exploited, the working class,’ one East End skinhead explained. ‘It’s hard for us to fight for our job and our house, but with them here as well, trying to get our houses, it’s another opposition … I’ll tell you another thing, when you stand next to these people that have just come over here, they fucking stink.’35

Although the summer of 1970 marked the high point of the skinhead panic, they did not go away. Indeed, thanks to a stream of astonishingly popular thrillers by the pulp novelist James Moffatt (writing as Richard Allen), skinhead culture spread well beyond the capital, appealing to disaffected working-class teenagers seduced by its heady mixture of violence, resentment and tribal identity. Racism was always a major element of its appeal, cementing the loyalties of men who felt adrift in a world of deep economic anxiety and social change. ‘It was like the black hole of Calcutta down my factory,’ lamented one East London hooligan who joined West Ham’s notorious Inter-City Firm. ‘You’d get them all standin’ in a mob, all talkin’ that chapatti language an’ all that, an’ you never know whether they’re talkin’ about you.’ He looked forward to the weekend rampages against immigrants, when he and his fellow supporters would ‘steam round an’ kick fuck out of the Pakis’ – a chance, as he saw it, to proclaim their white working-class masculinity, to stand up to the effeminate middle classes and job-stealing immigrants who were trying to keep them down. As skinhead culture merged almost seamlessly into the growing culture of football hooliganism, so the post-match ‘Paki-bashing’ became just another weekend ritual alongside the pie and the pints. And even after skinheads had faded from the headlines, their attacks continued to blight the lives of immigrant families. In London alone, Gurdip Singh Chaggar was killed in Southall in 1976, Altab Ali, Kennith Singh and Ishaque Ali were murdered in Whitechapel, Newham and Hackney respectively in 1978, and Akhtar Ali Baigh was killed in Newham a year later. In the East End, reported a local trade union group, there were 110 racist attacks just in the autumn of 1977, ‘an almost continuous and unrelenting battery of Asian people and their property’.36

What made the racist violence of the 1970s even more unsettling was that many immigrants felt utterly abandoned by the authorities. ‘The Pakistanis of East London’, one observer remarked in April 1970, ‘have unquestionably lost confidence in the police’, and who could blame them? Despite the fact that London now had an immigrant population in the hundreds of thousands, the Metropolitan Police was staggeringly white, with only ‘ten coloured policemen’, to use the terminology of the day. Although the new Met commissioner Robert Mark devoted considerable effort to attracting more black and Asian recruits, by 1976 there were just 70 black police officers in a force more than 22,000 strong. Many encountered persistent mockery and hostility from their fellow recruits, which was hardly surprising given the prevailing prejudice within the ranks. But London was hardly exceptional. Most police officers, reported the Select Committee on Race Relations and Immigration in 1971, believed blacks were more likely than whites to be criminals, even though the statistics actually showed that levels of crime among blacks were no higher. In Nottingham, a city with almost 20,000 immigrant residents but not a single black or Asian policeman, efforts to organize race relations seminars were undermined when, at the end of one session, a group of veteran officers started chanting ‘Enoch, Enoch, we want Enoch!’ And when the sociologist Maureen Cain investigated police attitudes in 1973, she reported that most officers thought ‘niggers’ or ‘nigs’ were ‘pimps and layabouts, living off what we pay in taxes’. ‘Have you been to a wog house?’ one officer asked her. ‘They stink, they really do smell terrible.’37

For many immigrant families, police hostility was an unpleasant but sadly inevitable part of life in Heath’s Britain. In Nottingham, 31 per cent of West Indians and 36 per cent of Pakistanis thought that the police gave them ‘less favourable treatment’. Many complained that the police turned a blind eye to racist attacks: one man, who called the police after a neighbour’s son smashed his windows, recalled that they were initially very sympathetic, but changed their tune when they discovered that the boy was white. Even more distressingly, one in five Nottingham immigrants claimed that the police regularly beat up blacks and Asians – an allegation dismissed at the time, but one that matches accounts from other cities. For black youngsters growing up in London, Mike and Trevor Phillips wrote, the police were ‘a natural hazard, like poisonous snakes or attack dogs off the leash’. A survey in 1972 found that almost all of the capital’s West Indians thought the police discriminated against them, and one in five claimed to have had direct experience of police racism. One man later remembered that ‘as black kids, you couldn’t go anywhere without a copper creasing your collar … and if they didn’t like your face, if your face didn’t fit, or you was a bit too lippy, as most black kids are, you’d get a little kicking’. Similarly, Herman Ouseley, later chairman of the Commission for Racial Equality, recalled that in Brixton he ‘didn’t even wait for a bus’, since ‘just being black and being on a street was very frightening because you were seen as acting suspiciously’.38

Even at this early stage there were warnings that police harassment was stoking the flames of racial tension. In 1970 black protesters besieged the police station in Caledonian Road, Islington, while a year later repeated police raids on the Mangrove restaurant in Ladbroke Grove culminated in the embarrassment of the Mangrove Nine trial, where a white jury acquitted seven out of nine black activists accused of affray. Black protest often focused on the excessive zeal, to put it mildly, of the aggressive Special Patrol Group, a kind of force within the force, which was repeatedly sent into South London to target young black muggers. In 1975 the SPG stopped 14,000 people and arrested some 400, almost all of them young black men, in Lewisham alone. The tabloid press often hailed the SPG as the cutting edge of the modern force; to many Caribbean families, however, it was the epitome of white racism and police harassment. But black patience was not inexhaustible. As early as 1972 there were reports that local groups were forming self-defence associations, and representatives of the West Indian Standing Conference warned a parliamentary committee that unless the police ended their ‘systematic brutalization of black people’, there would be ‘blood on the streets of this country’. This was no exaggeration: two years later, scuffles at a fireworks display at Brockwell Park, Brixton, escalated into a pitched battle between white policemen and black youths, with allegations of brutality on both sides. Miraculously, nobody was seriously hurt, but it was a sign of things to come.39

While the harassment of ethnic minorities undoubtedly reflected the prejudice shared by many police officers, it also owed something to the intense pressure on them to crack down on public disorder. Police officers were told to keep an eye out for ‘coloured young men’ on the London Underground, for example, not just because their superiors had highly reactionary ideas about black criminality, but because almost every week the press were demanding a more aggressive approach to policing. The Heath years were a period of deep anxiety about law and order, not only because one corner of the United Kingdom seemed on the brink of civil war, but because so much of modern life seemed infected by the virus of public violence. What the Mirror called ‘AGGRO BRITAIN’ was more than fantasy: it seemed a genuine reflection of a world in which there was an armed bank robbery in London every six days, police estimated that 3,000 professional robbers were loose on the streets of the capital, and almost no major football match passed off without drunkenness, damage and disorder. The statistics in London alone made sobering reading. In 1968 the Metropolitan Police had reported 299,000 indictable crimes, but by 1971 the total had surged to 340,000, rising to 414,000 in 1974 and 567,000 in 1978. (It is worth noting, though, that these figures are still small compared with the peak in the early 1990s, when there were 945,000 offences a year.)40

Behind these figures lay an unsettling sense that the times were out of joint, that something had gone wrong, that the forces of violence and disorder were gaining the upper hand. ‘It was a year which began and ended in violence … the year of the international terrorist,’ The Times concluded gloomily at the end of 1972, looking back at the massacres in Londonderry and Munich, the American bombing of North Vietnam and a rash of terrorist atrocities in Italy, Israel, Japan and the United States, not to mention the domestic controversies of the miners’ strike, the collapse of Heath’s industrial relations plan and the furore over the Ugandan Asians. Amid this international lawlessness and domestic disarray, it was no wonder so many people thought the barbarians were at the gates, or that so many – the overwhelming majority, in fact – supported the return of the death penalty. ‘Violence has reached such a pitch’, recorded James Lees-Milne, in words that would undoubtedly have drawn approving nods from millions of his countrymen, ‘that only violence can restrain it. The thugs of this world cannot be checked by light sentences and comfortable cells, but by being executed, got rid of by the quickest, least offensive means, a prick in the arm and a gentle slipping away to God knows where.’41

Of all the symptoms of public disorder, one of the most frightening was the rise of mugging. The word first appeared in the British press in August 1972, when an elderly widower, Arthur Hills, was stabbed to death outside Waterloo station as he was going home from the theatre. It was, said the Mirror a few days later, ‘a frightening new strain of crime’, imported from the United States, where such atrocities were apparently endemic. Of course it was not really new at all: as a leading QC pointed out in The Times a few days later, mugging was almost exactly the same as the ‘garrotting’ that had obsessed Victorian headline writers a century before. But the word carried disturbing connotations. Since the late 1960s, British papers had reported with horror the surge in violent crime across the Atlantic, where American cities seemed to be sliding into a brutal cycle of decay, delinquency and disorder. Mugging was an American phenomenon, associated with the black gangs who supposedly controlled the mean streets of cities like New York, Chicago and Detroit, and British newspapers shuddered at the thought that it was coming east. ‘Britain seems to be edging too close for comfort to the American pattern of urban violence,’ lamented the Birmingham Evening Mail in March 1973 after a controversial mugging case in the city’s Handsworth neighbourhood. ‘I have seen what happens in America where muggings are rife,’ agreed Jill Knight, Edgbaston’s Conservative MP. ‘It is absolutely horrifying to know that in all the big American cities, there are areas where people dare not go after dark. I am extremely anxious that such a situation should never come to Britain.’42