These are the greatest days England’s ever gone through. The people are rising at last!

– Mike Rawlins in Till Death Us Do Part, 30 January 1974

Went to bed & dreamed that I was attending a political meeting addressed by Harold Wilson. I was talking to him & he was complaining of the sparse attendance, and I saw Heath in the front row smiling and wearing a ridiculous square shouldered ladies’ musquash coat. It was absurd.

– Kenneth Williams’s diary, 9 March 1974

The coach left from Chorlton Street, Manchester just after eleven on Sunday evening, picking up speed as it reached the M62. It was packed with servicemen and their families – young men telling jokes under their breath, young wives trying to get some sleep, children snoring or staring out of the window – who had spent the weekend with friends and relatives in Manchester, and were now heading back to their barracks in Catterick and Darlington. Normally they would have taken the train, but of course there were no trains, because of the ASLEF dispute that had crippled the railway network since December. So the army had booked a North Yorkshire coach company to pick them up. As it happened, the driver, Rowland Handley, was a director of the firm, and knew the route well. After twenty minutes he stopped in Oldham to pick up a second group of passengers, and half an hour later in Huddersfield he collected some more. By midnight he had almost reached Leeds, making excellent time along the motorway, and behind him many of the passengers were fast asleep. And then it happened.

One moment the coach was cruising smoothly and effortlessly through the night. The next there was an almighty, heart-stopping bang, as 25 pounds of high explosive went off in one of the luggage lockers. In that instant, the entire back of the coach was torn apart, the force of the blast sending pieces of twisted, blackened metal spinning across the carriageway. At the front, Rowland Handley, who had no idea what was happening, struggled to keep his grip on the wheel as shards of the shattered windscreen flew into his face and the vehicle lurched across the road. Somehow – he never knew how – he managed to steer what remained of the coach towards the side of the road, braking desperately, blood pouring from his forehead. He turned off the engine, fumbled for a torch, and heaved himself trembling from the cab. Mr Handley could hardly have realized it in those desperate, frantic moments, but by keeping the coach on the road so long he had probably saved dozens of lives. But what he saw next would live with him for ever. He had served in Cyprus with the RAF, but he had never seen anything like it. The entire back section of the coach had simply been shredded. As he disbelievingly moved his torch over the wreckage, he saw ‘a young child of two or three lying in the road. It was dead. There were bodies all over.’

The explosion was so great that it shook buildings half a mile away. But to many of the survivors it seemed like a terrible nightmare from which they would soon awake. ‘I just thought it was a dream, I just thought I’d fallen asleep into a bad dream and I just kept on shaking my head and trying to come round,’ said David Dendeck. ‘Then I found out it was real. I was just under all this metal. There was blood coming in my eye … It was dark and there were people screaming and running up the verge on the grass. I could hear my sister on the other side of the coach shouting for me.’ Another passenger, 20-year-old Trooper Michael Ashton, had been sitting behind the driver when the bomb went off. Now, staggering around the side of the vehicle, he came across ‘a girl about 17’, who had been thrown ‘200 yards back up the road’. She was hysterical, he remembered; her legs were crumpled and useless. Around her lay more bodies, motionless, bloody, some of them women and children. ‘It was just absolutely unbelievable,’ said John Clark, a passing motorist who stopped to help. ‘The smell was what upset me really. It was dark so you couldn’t see how bad the injuries really were, but it was the smell of it. It was absolutely total carnage.’

Eleven people died that night, Sunday, 4 February 1974, victims of the Provisional IRA. Eight of them were soldiers in their late teens or early twenties. One of the dead soldiers, 23-year-old Corporal Clifford Houghton, had been travelling with his wife Linda and their two children, 5-year-old Robert and 2-year-old Lee. All three were killed alongside him, an entire family wiped out in the blink of an eye. Fifty people were injured, many of them seriously; one, a 6-year-old boy, was so badly burned that doctors feared for his life. For years afterwards, the survivors had to cope with nightmares, trauma and disability: as one Oldham lad, just 18 when the bomb went off, remarked at the unveiling of a memorial thirty-five years later, it was a moment that, try as he might, he could ‘never forget’. But of course he was one of the lucky ones; four days after the atrocity, a twelfth victim died of his injuries, his death casting a dark shadow over the first day of the general election campaign.1

It was not the first time the Provisionals had launched attacks on the mainland. In March 1973 they had set off bombs at the Old Bailey, while in August and September they had planted explosives at Harrods, King’s Cross and Euston, as well as in Birmingham, where a soldier had been killed trying to defuse the bomb. But this was something new: a devastating, indiscriminate atrocity, extinguishing the lives of a dozen people. In the next few days, newspaper columnists and politicians clamoured for the reintroduction of the death penalty for terrorists. And in the panicked rush to judgement, a mentally ill but entirely innocent woman, Judith Ward, was eventually sent to prison – the first in a series of miscarriages of justice born out of the intense pressure to find scapegoats for the murderous handiwork of the IRA.

The horror on the M62 seemed yet another indication of a society in which the veneer of consensus had cracked, a society lurching into violence and disorder. And although the election campaign meant that the coach bombing quickly disappeared from the headlines, it was far from the last attack on British soil. On 13 February a second bomb ripped through the National Defence College in the sleepy village of Latimer, Buckinghamshire. Ten people were badly hurt; no one, miraculously, was killed. But by now terrorism seemed to be the stuff of everyday life. Quite apart from the slaughter in Northern Ireland, the previous six months had seen a hijacking in Austria, an embassy bombing in Marseilles, a massacre at Rome airport, the assassination of the Spanish Prime Minister, and the kidnapping of the American heiress Patty Hearst. Not even the Royal Family, ‘the symbol of the nation and of the standards which Britain has lived by’, was immune. On the evening of 20 March, as Princess Anne and Captain Mark Phillips were returning from a charity event for disabled children, an armed madman held up the Princess’s car in the Mall and told her to get out. ‘Not bloody likely!’ she snapped, and in the ensuing melee she managed to get away. But it was yet another sign, said The Times, that ‘acts of casual terrorism’ had become ‘part of the texture of our lives in the 1970s’. ‘There is no pause in violence,’ it lamented; it was ‘as though the vanguard of anarchy were at loose in the world … We do not suffer this pressure of anarchy more than other countries, but we do not suffer it less either. It is a sign of a civilization in regression, turning back from achievement to a neobarbarism.’2

It was against this dark and bloody backdrop that Edward Heath launched his great election gamble. It was, the press agreed, an election without precedent in modern British history. Both the Sun and the Mirror called it the ‘Crisis Election’: every morning the slogan adorned their front pages. What was at stake, said The Times, was ‘more than one strike: it is the future of the country’. Nobody could remember an election in grimmer circumstances. The Harris poll found that nine out of ten people thought ‘things are going very badly for Britain’, while only two out of ten expected the desperate economic situation to improve over the next twelve months. And while the politicians warned darkly of bitterness and extremism, and exchanged accusations that their opponents were dividing the country, perhaps the really depressing thing was the sheer passivity, the gloom and apathy that seemed to have enveloped the general public. The experience of the last ten years, wrote the Guardian’s perceptive columnist Peter Jenkins the day after the election was declared, proved only that ‘neither party’ could handle Britain’s problems. As the authoritative Nuffield study of the election put it a few months later, ‘it was an unpopularity contest between two contenders widely seen as incompetent on the major issues’.3

Heath set out his case for re-election in the first Conservative election broadcast, three days into the campaign. The theme was Heath as the man of destiny, the strong leader guiding the nation through stormy waters. At the beginning, supposedly ordinary voters told the camera that he had ‘done all that is expected of a Prime Minister’, and would ‘get England back on its feet’. Then Heath himself told the audience that his quarrel was not with the broad union movement but with ‘a small group of extremists’. It was ‘time to take a firm line’, he said, ‘because only by being firm can we hope to be fair’. This was the theme of the manifesto, too, which was entitled Firm Action for a Fair Britain. Some readers were shocked by the manifesto’s strident rhetoric: not only did it claim that the Opposition had been taken over by ‘a small group of power-hungry trade union leaders’ who were ‘committed to a left-wing programme more dangerous and more extreme than ever before in its history’, it warned that a Labour victory would be a ‘major national disaster’. In fact, even this was only a watered-down version of Nigel Lawson’s original draft, which had claimed that ‘the very fabric of our society is at risk’, only to be rejected by Tory colleagues who thought it was too ‘hard and anti-union’.4

Beneath the surface of the Conservative campaign, which was spearheaded by Heath at his most presidential, there ran an undercurrent of deep anxiety, even paranoia, about the consequences of defeat. The long months of tension had taken their toll, and on 19 February the Tories’ advertising team overstepped the mark with a particularly embarrassing example of hysterical scaremongering. On screen, pictures of Harold Wilson and James Callaghan dissolved to show the terrifying features of Michael Foot and Tony Benn, while a narrator warned that Labour would confiscate ‘your bank account, your mortgage and your wage packet’. ‘It wouldn’t take much more of a move to the Left,’ the commentary went on, ‘and you could find yourself not even owning your own home.’ On screen, a young couple’s house obligingly vanished. Not surprisingly, Wilson was furious, playing back the tape at his morning press conference to show how low the Tories had sunk. And not unreasonably the Nuffield study later called it ‘a sorry broadcast in its ethical blindness, its clumsy cascade of visual gimmicks, and its abysmal view of the electorate’s intelligence’. Even the Tory high command was embarrassed, and Wilson was only slightly mollified when Lord Carrington offered a formal apology.5

Oddly, however, the great flaw in the Conservative campaign was that in general it was not strident enough. When Carrington asked Nigel Lawson to redraft the manifesto and produce something ‘more One-Nation’, he was echoing the views of Heath himself, who was determined not to make the election a confrontation between the government and the miners. But this was a very strange position to take, because clearly at one level the election was a contest between the government and the NUM. The result was that apart from its anti-Labour conclusion, the Tory manifesto was a very vague and woolly production indeed, with plenty of bluster about firmness and fairness but no detailed policies or sense of direction. As so often, Heath ended up falling between two stools, trapped between the need to mobilize opinion against the unions on the one hand, and his One Nation instincts on the other. If he wanted a sweeping new mandate, he needed to whip up public outrage against the miners, to emphasize the desperate urgency of the situation, to hammer home the themes of crisis and betrayal. Instead, he talked of fairness and moderation: ideal themes for the Labour leader, perhaps, but surely not the Conservative one. Even his best speech of the campaign – a resounding reassertion of One Nation principles in Manchester’s Free Trade Hall, presenting the Tories as ‘the union for the unemployed and the low paid … for those in poverty and for the hard pressed’ – sounded like the kind of thing Harold Wilson should be saying. It was one of the supreme ironies of Heath’s career that when it mattered most, a politician often caricatured as a callous reactionary could not bring himself to live up to his billing.6

But while Heath’s campaign was at least slick and confident, his Labour opponents seemed to be in a very feeble state. Not only were senior figures still nursing their wounds after their battle over Europe, but many were deeply unhappy with their own manifesto, which promised the most radical programme since the 1930s. The product of months of infighting, it reflected a leftward tilt at the Labour grass roots and was heavily influenced by the ideas of the economist Stuart Holland, then a great favourite of the Shadow Industry Secretary, Tony Benn. Gone was the talk of science and technology, the rhetoric of ‘planned, purposive growth’, the pledges of dynamic modernization that had marked Labour manifestos in the 1960s. In their place, the new manifesto promised ‘a fundamental and irreversible shift in the balance of power and wealth in favour of working people and their families’ as well as ‘greater economic equality in income, wealth and living standards’, and measures ‘to make power in industry genuinely accountable to the workers and the community’. It committed the next Labour government to ‘a fundamental renegotiation of the terms of [EEC] entry’ and a national referendum on British membership. And despite the nation’s parlous economic condition, the manifesto promised a range of new wealth and property taxes, the abolition of Heath’s industrial relations apparatus, and extensive new spending plans for health, education and pensions – even though it was far from clear that there would be enough money to pay for them.7

Potentially the most radical commitment, though, was the promise to set up compulsory planning agreements with industry and a National Enterprise Board (NEB) to take over firms ‘where a public holding is essential to enable the Government to control prices, stimulate investment, encourage exports, create employment, protect workers and consumers from the activities of irresponsible multi-national companies, and to plan the national economy in the national interest’. These were words that gladdened the hearts of radical Labour activists, but they horrified most businessmen. And more than any other part of the programme, they reflected the ideas of Tony Benn and his intellectual circle. Having ‘reincarnated’ himself (as Michael Foot scathingly put it) from the former Viscount Stansgate into plain Tony, the tribune of the plebs, Benn now believed that only massive state intervention could make Britain both egalitarian and competitive. His diaries brimmed with messianic expectation, and he eagerly looked forward to the ‘great crisis of capitalism’ when a ‘popular front’ including Marxist and far-left groups could take power. ‘I think we would need the Emergency Powers Act and an emergency Industrial Act,’ he noted, ‘which would give the Minister absolute power to deal with the situation.’8

To all but those on the far left, talk of ‘emergency powers’ was potentially terrifying stuff. Even Benn’s own mentors often shuddered at his radical intransigence. Stuart Holland, the intellectual godfather of the state holding company scheme, wrote later of his horror at Benn’s ‘dogmatic’ and wildly unrealistic vision of a socialist Little England sealed off from the world economy. And on the right, where Benn had once been seen as an amusing, eccentric but ultimately harmless figure, he now loomed as the incarnation of socialist devilry, the Red Menace made flesh. By September 1972, Radio Four’s Today programme had dubbed him ‘the most hated man in Britain’; in the Sunday Express a month later, Michael Cummings portrayed him in full Nazi stormtrooper regalia. The Times accused him of stirring up class warfare; the Sunday Telegraph called him ‘Bolshevik Benn’; even the Observer thought that he was ‘hysterical’. But the more the press demonized him, the more Harold Wilson tried to ignore him, the more Shadow Cabinet colleagues like Denis Healey and Anthony Crosland openly laughed at him, the more Benn knew he was right. Even the history books he read in his spare time fuelled his sense of mission: after working his way through a pile of books on the Levellers, he lamented that ‘the Levellers lost and Cromwell won, and Harold Wilson or Denis Healey is the Cromwell of our day, not me’. And yet as ‘Chairman Tony’ built up support among Labour’s disillusioned grass-roots activists, he seemed to be destined for a much more successful career than his radical heroes. In preparation for taking power, he even drafted a plan for the NEB to take over ‘twenty-five of our largest manufacturers’ – a tremendous first step, as he saw it, towards an economy liberated from the multinational corporations, and based on the principles of public ownership and workers’ control.9

In the City, once the supreme symbol of Heath’s new capitalism, the Labour manifesto felt like a declaration of war. In almost every section of society, complained the Banker, could be heard ‘the pure emotional assertion that the City is no more than a band of robbers, who contribute little to the country whilst making fortunes for themselves’. This was not just confined to the far left: it was ‘probably what most people in Britain believe, either half-heartedly or completely’. How many commuters could be ‘sure that the wives they leave behind each morning do not secretly think so themselves?’ But the Banker’s greatest ire was reserved, not for the BBC scriptwriters, pulp-novel authors and saloon-bar pundits who popularized the idea of the Square Mile as rapacious and corrupt, but for Her Majesty’s Opposition. ‘To people in the City itself,’ it explained, ‘the Labour Party and many other critics appear strictly mad. What on earth can be the national interest in destroying or sniping at one of the few really efficient and competitive sectors of its economy?’ The City could hardly be blamed ‘if it just decided to pack its bag and go somewhere where the sky is blue, the natives friendly and where a man’s money is his own. Just possibly, that is what may happen. Messrs Wilson, Benn et al would then find themselves barking at an empty fortress.’10

Behind the City’s fury lay not just the predictable self-interest of the wealthy and well connected, but a growing sense of panic about the nation’s economic future. By February 1974, the days when the City had been the go-ahead incarnation of Edward Heath’s new Britain seemed a very distant memory. And for all the gleaming modernity of the new Stock Exchange Tower, images of the Great Depression now loomed larger than exhilarating visions of future prosperity. Since November, the City had been engulfed in a perfect storm, its confidence shattered by a plunging property market, soaring oil prices and the biggest credit squeeze anyone could remember. Nobody doubted that Anthony Barber had been right to put the brakes on: the alternative would have been inflation of South American proportions. But for the so-called ‘secondary’ banks that had lent so much money to developers during the Barber boom, the implications of his credit controls were simply devastating. Not for the first time, and certainly not for the last, many banks had over-extended themselves in the pursuit of profit, blind to the reality that one day boom would turn to bust. But now the great property bubble had burst, and nemesis had caught up with them. ‘We used to go to visit the Governor of the Bank of England every Wednesday,’ the deputy chairman of the Stock Exchange later recalled, ‘and listen to the appalling news of one bank after another closing its doors.’11

This was no exaggeration. By Christmas, the value of many fringe banks had dropped by as much as a third, and there were genuine fears that the entire structure might topple like a house of cards. And as oil prices mounted, as Britain went on a three-day week, as talks between the government and the miners dragged on, anxiety turned to panic. House prices were plummeting; land values dropped by about half in barely a year; even the markets in vintage cars, in antiques, in works of fine art, burst like popped balloons. Between mid-November and mid-December, the FT30 share index lost a quarter of its value. By 28 January, four days after the NUM executive had voted to hold its national strike ballot, the index had fallen to just 301.6 – a drop of almost half since its peak in May 1972. It was the worst bear market in history. Britain must be prepared, declared the Governor of the Bank of England, for a decade of austerity in order to settle the yawning budget deficit. Even Jim Slater, once the incarnation of buccaneer capitalism, now cut a distinctly gloomy figure. ‘There’s a hurricane blowing through the financial world,’ he told one reporter. ‘You must put your head down and wait for the hurricane to finish blowing.’12

Ten years earlier, Harold Wilson might have been sympathetic to the City’s plight. But the mood inside the Labour Party was now very different from the technocratic pro-growth ethos of the early 1960s. With its local branches increasingly dominated by the middle-class ‘polyocracy’ and its leadership ageing and passive, Labour had swung further to the left than at any time since the 1930s. Even relatively centrist politicians like the Shadow Chancellor, Denis Healey, now played to the radical gallery. In his reply to Anthony Barber’s austerity measures, Healey had called for ‘increased taxes on luxuries such as fur coats, wines and brandy’ to pay for food subsidies, which, as even he admitted later, was a totally ‘inadequate’ response to the crisis. Now he boasted that he would levy whopping new taxes on ‘food manufacturers and retailers’ and would ‘squeeze the property speculators until the pips squeak’. To Healey this was just good knockabout electioneering stuff. But to the Conservative middle classes it seemed a bone-chilling warning, a sign that the ‘socialists’ were hell-bent on class warfare. The details of Healey’s remarks were lost amid the hysteria; people told one another that he had pledged to squeeze ‘the rich’ until the pips squeaked. Newspaper cartoonists showed Labour’s leaders as beetle-browed Bolsheviks, their hands reaching out to grasp the levers of power and the wealth of the middle classes. In the Express, Cummings drew Wilson and his colleagues as French revolutionaries encouraging Joe Gormley to bring down the guillotine on Ted Heath; in the Mail, Emmwood showed Wilson tucked up in bed beside a very dodgy-looking character in dark glasses. ‘LEFT-WING EXTREMISTS’ reads the sign on the latter’s placard. In case there was any doubt, his pyjamas are patterned with the hammer and sickle.13

Quite apart from the problem of finding the money to pay for more nationalization, the obvious problem with the Labour manifesto was that not even its own supporters believed in it. Although committed activists loved Tony Benn’s proposals, the great mass of relatively apathetic Labour voters did not. The party’s private polls found that only 37 per cent of Labour supporters wanted to see more public ownership, with 44 per cent against. Only 30 per cent of Labour voters agreed with the nationalization of North Sea Oil, only 26 per cent supported the nationalization of land, and just 12 per cent agreed with the commitments to nationalize the ports, aircraft industries and shipbuilding. The proposed National Enterprise Board, meanwhile, was overwhelmingly unpopular: for all Tony Benn’s passionate salesmanship (or perhaps because of it), only a pitiful 6 per cent of Labour voters and 7 per cent of trade unionists thought it was a good idea. And on top of that, almost none of the party’s senior figures believed in their own commitments. In the Shadow Cabinet, Benn’s NEB scheme was particularly unpopular. ‘Why don’t we nationalise Marks and Spencer to make it as efficient as the Co-op?’ Healey asked sarcastically, while Tony Crosland and Edmund Dell made no secret of their belief that the nationalization programme was total madness (‘half-baked’ and ‘idiotic’ were Crosland’s characteristically trenchant words).* Even left-wingers were uneasy with Benn’s utopian plans. Michael Foot told Benn that ‘the twenty-five companies proposal was crazy’ and asked in disbelief: ‘Do you think we could win the Election? Do you want to win the Election? What are you up to? What are you saying?’ And Jack Jones, the old Communist warrior, warned Benn that the working classes ‘didn’t want airy-fairy stuff. Nationalisation was unpopular; it failed.’ ‘Why don’t you make a speech on pensions instead of all this airy-fairy stuff?’ Jones asked him. But Benn knew what was going on: the TGWU boss had ‘completely abandoned his serious left-wing programme’. Like Foot, like Healey, like Wilson, like all the rest of them, the Emperor Jones was just another right-wing sell-out.14

In many ways it was a sign of Harold Wilson’s declining authority that he was saddled with a manifesto he patently did not want. But it was also a sign of his growing detachment from domestic politics: his physical and intellectual weariness, his declining ambition, his sheer lack of hunger. In the 1960s he had placed himself at centre stage, hogging the limelight like an American presidential candidate. But now he presented himself as merely part of a team, allowing Callaghan and Healey to dominate the daily press conferences and his latest protégée, Shirley Williams, to become the star of the television broadcasts. They were ‘the wise old firm’, ran the message, ‘who could get on with the unions and get the country back to work’. Meanwhile, the extravagant promises of the manifesto were quietly forgotten. Even the word ‘socialism’ seemed to have disappeared, Wilson using it only twice in his speeches, and then only in the vaguest terms. Although he had clung on to the party leadership with the tenacity of a limpet, he had long since given up being the candidate of change, the modernizer who would lead Britain into a brave new world of progress and equality. Now he was content to play the trusted old family doctor, the voice of reason, the pipe-smoking reincarnation of Stanley Baldwin. Tony Benn was disgusted, recording that ‘all this “national interest”, “working together”, “keep calm and keep cool”, and “a Labour Government will knit the nation” seems absolute rubbish’. But even Labour right-wingers felt a twinge of unease at what seemed a highly disingenuous campaign. David Owen later called it the ‘shabbiest’ campaign he had ever been involved in. And Roy Jenkins, now even more detached than his leader, thought that they deserved to lose, and hoped that they would.15

No election campaign had been attended by more publicity than the contest in February 1974. Both the BBC and ITV ran ‘Election 74’ bulletins several times a day, while the newspapers were dominated by campaign stories. But what was also unprecedented, at least since the war, was the level of sheer partisanship. Only the Guardian refused to commit itself, calling rather limply for a ‘three-way balance’. The Mirror, as usual, backed Labour, but Rupert Murdoch’s Sun, hitherto a Labour paper, urged its readers to re-elect Heath. What was really striking, though, was the sheer intensity of the Conservative papers’ rhetoric, which reawakened memories of the Zinoviev letter and the anti-socialist scares of the 1920s. A Labour government would be ‘complete chaos: ruin public and private’, said the Telegraph, which thought that their manifesto illustrated Wilson’s ‘craven subservience to trade union power’. If he won, agreed the Sun, the result would be ‘galloping inflation and the sinister and ever-growing power of a small band of anarchists, bullyboys and professional class-war warriors’.16

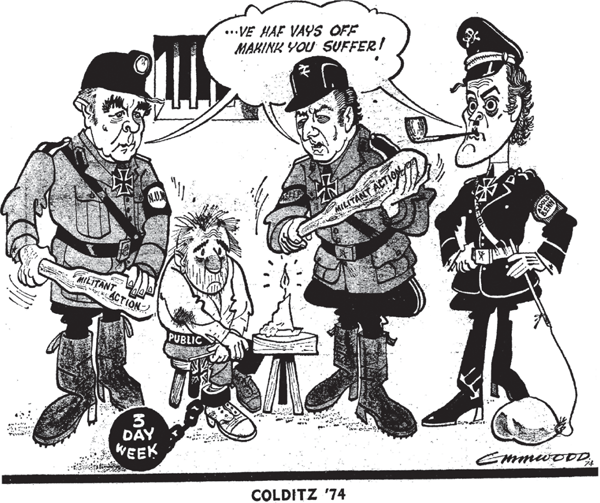

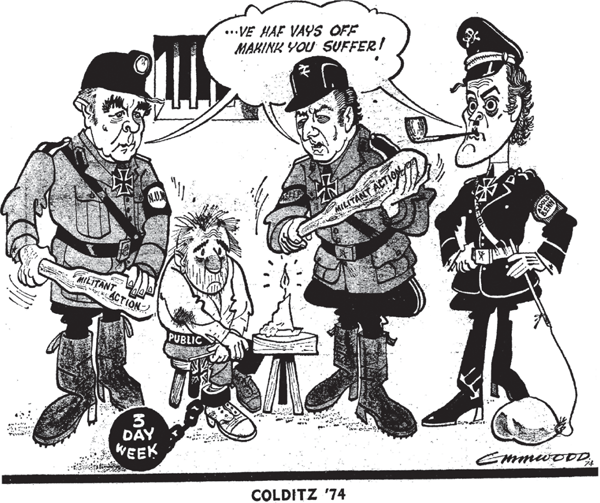

By contrast, the Daily Mail – which had prepared but did not run a story about Wilson’s murky finances – directed much of its fire at the miners, blaming them for ‘producing the worst inflation in our history’. But it reserved some of its ammunition for Tony Benn, who for the right had become the ultimate demonic stage villain. One Mail cartoon showed Benn as a Gauleiter ordering Joe Gormley to torture the British public with the words ‘ve haf vays off makink you suffer!’ Another showed him as a blacksmith, setting about the pound with a hammer and sickle while hot air pours out of his forehead. And other Tory papers were hardly more generous: on the last day of the campaign, the Evening Standard ran a piece by Kingsley Amis explaining why Benn was ‘the most dangerous man in Britain’. The Evening News, meanwhile, ran an extraordinary article by the retired MI6 officer and hard-right Tory candidate George Young, who claimed that there were ‘40 or 50 Labour MPs for whom the Labour label is cover for more sinister roles’. They formed, he said, a ‘Black Hand Gang’, working alongside the ‘Red Hand Gang’ in the unions.17

Yet whether commentators favoured Heath or Wilson, almost none doubted that the Prime Minister would win; indeed, many expected a landslide. Bookmakers had the Tories favourites at 2–1 on, a stark contrast with their underdog status back in 1970, and by the end of the first week Harris, NOP, ORC and Marplan all gave them a lead of between 6 and 9 per cent. Now that battle had been joined, Heath seemed unusually relaxed and confident, enjoying the liberation of campaigning rather than governing. ‘Presidential’ was the word that often sprang to mind: one profile even called him ‘the iron man’, stern and authoritative. And as poll after poll forecast a clear Tory lead, a sense of inevitability began to take hold. Irrespective of how they planned to vote themselves, no fewer than six out of ten voters thought that Heath would win the election, compared with just two who expected Wilson to win. ‘The present one-sided picture of a relaxed and “statesmanlike” Prime Minster chastising the militants on behalf of the nation and a rather tired and rattled Labour Party swinging wildly,’ wrote David Watt in the Financial Times, ‘can only produce one result.’18

The second series of the BBC’s hugely popular Colditz was just starting when Emmwood drew this cartoon for the Daily Mail (7 January 1974). The miners’ president Joe Gormley and the railwaymen’s leader Ray Buckton wield the cudgels, ‘Adolf Benn’ gives the orders, and the public quails in terror.

In the Labour ranks, all was despondency. Only three days into the campaign, the political scientist David Butler, who co-edited the Nuffield election studies and had been an on-screen expert for the BBC since 1950, warned Tony Benn that he ‘foresaw a Tory landslide [and] was afraid that the Labour Party couldn’t survive’. The next evening, after spending the day touring a Bristol housing estate in the wind and rain, Benn noted that even Labour housewives had been ‘impressed by [Heath’s] arguments about the unions, about the miners, about Communists, about Militants, about strikes and about being fair but firm’. He felt ‘tired, exhausted and rather depressed’. So did Harold Wilson, whose aides worried that at heart he had already given up. In the old days Wilson had loved campaigning, but now Joe Haines, his faithful but acerbic press secretary, thought that his performances were ‘abysmal’, his speeches falling ‘from tired lips on to a leaden audience’. The Sunday Times thought he seemed ‘withdrawn, nervous, tentative, apprehensive, not to say distinctly bored with the whole affair’. He seemed ‘exhausted by the relentless treadmill of the campaign’, wrote his young policy adviser Bernard Donoughue, ‘his voice croaking and his eyes puffy and red-rimmed’. And every night, as Wilson relaxed with a large glass of whisky, he seemed older and more deflated, his faint hopes of victory slipping further away. It was like watching a condemned man, making the last inevitable journey to the scaffold. When Benn accompanied his leader to a rally with only six days to go, he was struck by the fact that Wilson seemed uncharacteristically nervous. ‘I think he does realise’, Benn wrote, ‘that he is perhaps within a week of the end of his political career.’19

There were, however, two chinks of light for Wilson. The first was the performance of the Liberal Party, whose popularity had been gradually rising since the leadership of Jo Grimond back in the late 1950s and early 1960s. In 1970 the Liberals had won less than 8 per cent of the vote, but since then they had enjoyed considerable success picking up disaffected Tory voters, especially after the Heath government ran into trouble in 1972. Almost beneath the surface of political events, the two-party system, based on class, regional, religious and family loyalties, was beginning to collapse under the impact of affluence and social change, and the Liberals’ reputation as ‘amiable, moderate and relatively harmless’ made them the ideal party of protest. Their by-election victories in late 1972 and mid-1973 confirmed them as a genuine force in British politics: indeed, Liberal candidates won more votes in 1973 than those of any other party, and by August they had broken through the 20 per cent barrier for the first time in polling history. Many observers expected their support to evaporate under the pressure of a general election, especially as their campaign was such a shoestring effort. But far from collapsing, the Liberals seemed more buoyant than ever. Their manifesto, with its promises of devolution and political reform and its impossibly vague economic agenda, evidently appealed to middle-class voters sick of the mudslinging of the other parties and nostalgic for a lost golden age of quiet moderation. And in their debonair leader, Jeremy Thorpe, they had the star of the campaign, a wry, charming television presence who took questions down a closed-circuit link from Barnstaple, making him seem somehow above the fray. In fact, Thorpe had a dark side that would have been entirely unimaginable in his rivals. But nobody knew that then.20

The other good news for Wilson was that despite the papers’ melodramatic talk of the ‘crisis election’, any sense of crisis seemed to be ebbing away. Although the miners had walked out on 10 February, the NUM shrewdly discouraged mass picketing and there were none of the violent clashes that had horrified the public two years before. Throughout the campaign, the miners kept a low profile, with only six men on each picket: Jim Prior wrote afterwards that they had been ‘as quiet and well-behaved as mice’. The anticipated power emergency, too, failed to materialize. The weather continued to be unseasonably warm, the three-day week seemed to be working, and power stations reported no shortages of fuel. Above all, Heath lifted the late-night television curfew on 7 February so that the election could get proper coverage. But with the schedules having returned to normal, many people took the attitude that the crisis was basically over.21

As the sense of urgency disappeared, so polls began to show that the miners’ dispute was fading as an election issue. By 15 February, when the latest Retail Price Index showed that prices had increased by a staggering 20 per cent in just twelve months, inflation was beginning to take over as the electorate’s chief anxiety. Concern about the unions began to recede: whereas 40 per cent had named strikes as a major issue on 8 February, only 24 per cent thought the same on 23 February – while twice as many were worried about high food prices. One by one, the newspapers that had originally claimed that this was a single-issue, government-versus-miners election changed their tune. From The Times on 12 February and the Telegraph on 18 February to the Sun on 21 February and the Mail on 27 February, they all decided that the ‘real issue’ was inflation after all.* This was good news for Wilson, who urged the voters to kick out ‘Mr Rising Price’, and promised that through a vague and undefined ‘Social Contract’ with the unions, he would be able to end the industrial unrest while still keeping prices down. But it was a disaster for Heath. He had set out to fight a ‘Who Governs’ election, not a referendum on his economic record – which by any standards, whether it was his fault or not, was frankly abysmal. Partly because of his own passivity, partly because of sheer bad luck, he had lost control of the election narrative.22

On Thursday, 21 February, a week before polling day, there was more bad news for Heath. Just after six that evening, the Pay Board issued its long-awaited report on the miners’ relativities, and it contained a bombshell. Far from being paid more than most manufacturing workers, as the Coal Board had claimed, it seemed that most miners were actually paid 8 per cent less – which obviously strengthened their case for a raise. Heath was furious, Wilson delighted, and the next day’s papers had a field day. ‘THE GREAT PIT BLUNDER’, roared the Mail. As Heath pointed out, the story was not quite as it seemed: it was really all a question of different statistical tables. But the damage was done. At that moment, many Tories later recalled, there was a tiny but palpable sense of the momentum shifting. What was more, some of Heath’s advisers were becoming distinctly alarmed by the Liberal surge, not least because nobody knew how it would affect the electoral map. Indeed, the Liberals’ rise defied all conventional wisdom: having been on just 12 per cent in Marplan’s poll on 10 February, they had surged to a stunning 28 per cent by the final Sunday of the campaign. Many people, it seemed, shared the views of Ronald McIntosh, who recorded that he and his wife had decided to vote Liberal for the first time because ‘if Heath gets back he will draw the moral that he was right all along and that would be quite disastrous … The Liberals have a good manifesto, they are sound on Europe and they are preaching moderation so they seem to us to be well worth voting for.’ Indeed, almost incredibly, four out of ten people now told pollsters that they would vote Liberal if Thorpe had a chance of holding the balance of power, and 48 per cent said they would vote for them if they could be the next government. At the very least, this was a resounding vote of no confidence in the two main parties. ‘Are you voting Liberal to get rid of Mr Heath or Mr Wilson?’ one voter asks another in a Times cartoon published two days later.23

With the polls still putting him around 5 per cent clear, Heath remained outwardly buoyant. Mulling over the figures at Chequers with his aides on the last Sunday of the campaign, he was reportedly ‘in a mood of high confidence’, the only doubt being ‘the magnitude of his victory’. Wilson, by contrast, seemed to have sunk into total despair. Seeing him in Birmingham that Sunday for a big meeting in the town hall, Roy Jenkins thought that his leader seemed ‘tired, depressed and expecting defeat, keeping going with some difficulty and gallantry until by the Thursday night he would have completed his final throw in politics’. Already Jenkins’s supporters were discussing the possibility of a leadership challenge: with Wilson bound to resign, it would surely mean a fight to the death against Callaghan, Foot and Benn. And on the Monday morning the mood was worse than ever, with a private poll suggesting that Labour were even further behind than they thought, and rumours circulating that the Daily Mail was about to produce its dossier on Wilson’s finances, his political secretary Marcia Williams, and their involvement in a strange land deal in the North of England. That night, Donoughue recalled, ‘the atmosphere was very bad … Wilson sat slumped, tired, sour, scowling, his eyes dead like a fish. He snarled at Joe about his speeches being “too sophisticated”. He drank brandy heavily.’ The next day, Wilson was scheduled to give his last major address in the Fairfield Halls, Croydon, and his aides were delighted to find a huge crowd outside. Only when Wilson walked in to a less than packed house did they realize that only 400 people had been queuing for the Labour leader. The other 1,700 had been waiting to see the film Trams, Trams, Trams in the hall next door.24

Yet it was not all dark clouds for Wilson. Over the last weekend a long-planned clandestine operation had been put into effect, and at its centre was perhaps the least likely man in Britain to lend his support to the Labour cause. Enoch Powell’s disaffection with his party leadership had been on record for years, but what few people realized was that he had been coming under intense pressure from middle-class Tories in his Wolverhampton constituency. During the fevered early weeks of 1974, his breach with both the leadership and his local association had widened even further. On 15 January, he had even declared that ‘it would be fraudulent – or worse’ for Heath to call an early election when neither the unions nor the miners had broken the law, and when the root of the crisis (as he thought) lay in Heath’s foolish incomes policy. And when Heath did call an election, Powell wasted no time in issuing a statement that sent shock waves through Conservative ranks. The election was ‘essentially fraudulent’, he declared, and ‘an act of gross irresponsibility’. Heath was trying ‘to steal success by telling the public one thing during an election and doing the opposite afterwards’. Powell could not ‘ask electors to vote for policies which are directly opposite to those we stood for in 1970’ – when Heath had, of course, ruled out any kind of incomes policy – ‘and which I have myself consistently condemned as being inherently impracticable and bound to create the very difficulties in which the nation now finds itself’. With regret, therefore, he would not be standing for re-election as a Conservative in Wolverhampton. For Powell, it was a searing emotional moment: he reportedly had tears in his eyes when he went into the Commons that evening. His friend Michael Foot rang and begged him to reconsider, calling his decision ‘courageous, brilliant – but reckless’. But when Powell’s mind was made up, there was no changing it.25

If Powell’s decision not to stand was a surprise, what followed was one of the biggest political shocks of the decade. Such was his contempt for Heath that party loyalty counted for little: all that mattered was to kick the erring helmsman out of Downing Street and replace him with somebody who might pull Britain out of Europe. A few days later, Powell’s friend Andrew Alexander, a columnist for the Daily Mail, contacted Wilson’s press secretary Joe Haines and told him that Powell wanted to issue a broadside against Heath: what would be the best timing for the Labour campaign? And on Sunday, 23 February, when Powell addressed an audience in the forbidding surroundings of the Mecca Dance Hall at the Bull Ring, Birmingham, even experienced commentators were left dumbstruck by his words. The overriding issue in this campaign, Powell said, was whether Britain was to ‘remain a democratic nation, governed by the will of its own electorate expressed in its own parliament, or whether it will become one province in a new Europe super-state under institutions which know nothing of political rights and liberties which we have so long taken for granted’. Under these circumstances, the ‘national duty’ must be to replace the man who had deprived Parliament of ‘its sole right to make the laws and impose the taxes of the country’. Powell never used the words ‘Vote Labour’. He did not have to. But when one of his listeners asked how they could be rid of ‘that confidence trickster, Heath’, he said calmly: ‘If you want to do it, you can.’26

Powell’s speech was a sensation. ‘ENOCH PUTS THE BOOT IN’, screamed the Sun; ‘THEY WEPT FOR ENOCH’, countered the Express. It is true that Europe was hardly the most rousing issue; until then it had barely featured in the campaign at all, and most people remained as confused and apathetic as ever. But Powell was still the most admired politician in the country, with an unparalleled ability to make headlines. And two days later at Shipley, where the hall was packed with 1,000 people and a further 3,000 were waiting outside, he was even more explicit. ‘I was born a Tory, am a Tory and shall die a Tory,’ he said, but he nevertheless hoped for a victory by ‘the party which is committed to fundamental renegotiation of the Treaty of Brussels and to submitting to the British people thereafter, for their final yea or nay, the outcome of that renegotiation’ – in other words, Labour. For Heath he had the deadliest insult of all, commenting that where U-turns were concerned ‘Harold Wilson, for all his nimbleness and skill, is simply no match for the breathtaking, thoroughgoing efficiency of the present Prime Minister’. At that, amid the shouting and applause, a heckler yelled: ‘Judas!’ Suddenly it was as though Powell had been connected to an electric current. His eyes blazing, his voice burning with conviction, his finger stabbing the air, he shot back: ‘Judas was paid! Judas was paid! I am making a sacrifice!’27

For Powell to be making the headlines just days before the election was the last thing Heath wanted. In the Express, Cummings portrayed the Prime Minister as a shipwrecked mariner, desperately scrabbling across a desert island towards the sanctuary of Number 10, while a gigantic black vulture in the shape of Enoch Powell moves in for the kill. But the shocks did not end there. Thinking that he was speaking off the record, the CBI’s secretary general Campbell Adamson told an audience that the Industrial Relations Act was now ‘so surrounded by hatred’ that the next government ought to repeal it and start all over again. Heath was furious and Adamson offered to resign, but the damage was done. More serious still was the news on Monday, 25 February, when the DTI’s latest batch of trade figures made for appalling reading. Back in 1970, a bad set of trade figures, showing a monthly deficit of £32 million, had helped to swing the election to Heath. But how times had changed! Now the figures showed an eye-watering £383 million deficit, the worst in history, thanks above all to the soaring price of oil. Heath insisted that the figures merely confirmed ‘the gravity of the situation’ and the need for a new mandate. But Wilson pounced. ‘On every count,’ he said, ‘the handling of the nation’s economy by this Conservative Government has been a disaster. Today’s devastating trade figures underline their incompetence. No excuse, no defence, no pretence can now hide from the country the fact that the economic crisis is deeper and more fundamental than the Conservatives have ever admitted.’ And as Roy Jenkins wryly remarked, it was very odd for Heath to claim that the atrocious figures somehow strengthened his case: ‘He presumably thinks a still worse result would have given him a still stronger claim.’28

On Monday night, Labour made its final televised appeal. As always, the broadcast emphasized the theme of teamwork, with one shadow minister after another – Michael Foot, Denis Healey, Shirley Williams – explaining how they would put Britain ‘on the road to recovery’, before Harold Wilson made some characteristically anodyne remarks about national unity: ‘Trades unionists are people. Employers are people. We can’t go on setting one against the other except at the cost of damage to the nation itself.’ By contrast, the Conservative broadcast on Tuesday evening was classic man-of-destiny stuff, opening with a montage of film clips and photographs while a narrator described Heath as ‘an extraordinary man. A private man. A solitary man. Perhaps single-minded sums it up … This is a man the world respects. A man who has done so much and yet a man who has so much left to do.’ Speaking woodenly but earnestly into the camera, Heath addressed the charge that he was too stubborn:

Is it stubborn to fight and fight hard to stop the country you love from tearing itself apart? Is it stubborn to insist that everyone in that country should have the choice and the chance to take his life and make of it what he can? Is it stubborn to want to see this country take back the place that history means us to have?

If it is – then, yes, I most certainly am stubborn …

I love this country. I’ll do all that I can for this country. And isn’t that what you want too? We’ve started a job together. With your will, we shall go on and finish the job.29

It was the same kind of patriotic appeal he had made in his final broadcast almost four years before, when he had been facing apparently certain defeat. Then, the polls had been wrong. This time, Heath had to hope they were right.

The Election Day headlines made encouraging reading for Conservative supporters. ‘It’s Heath By 5%’, said the Express, while the Mail predicted ‘A Handsome Win For Heath’. Neither paper mentioned that the polls had been quietly narrowing over the last few days, or that the Tory lead was now within the margin of error. In any case, all the major polling groups had Heath ahead by between 2 and 5 per cent. Among Tory insiders, the real question was not whether they would win, but the size of the victory, which would be crucial in claiming a new mandate: most reckoned they might get a 40- to 50-seat majority. Among Wilson’s aides, meanwhile, the great hope was that somehow they might deny Heath an overall majority, allowing them to claim a moral victory against the odds. Their mood was ‘sombre’, Bernard Donoughue remembered. Wilson himself seemed decidedly pessimistic: even as people were streaming out to vote, he told Donoughue that after his own Huyton constituency count he would tell the press that he was going back to the Adelphi Hotel, his traditional haunt on election night, but would in fact slip away to the Golden Eagle in Kirkby. There, Wilson said, he would watch the results. Then, early in the morning, he would leave by plane for London but secretly land at an airfield in Bedfordshire, from where he would drive to his Buckinghamshire farmhouse or some other rural retreat. Donoughue listened in total bewilderment, and then the penny dropped. ‘I suddenly realised what was behind all these bizarre plans,’ he recorded in his diary. ‘HW was preparing to lose! He was preparing his getaway plans. Unwilling to face the press, as anybody when beaten.’30

Election Day had dawned clear and bright, but by midday the weather was already changing, the dark clouds drawing in, the first drops of rain beginning to fall. At Conservative Central Office in London, the mood was nervous but still optimistic; in Liverpool, Donoughue walked with Marcia Williams along the Mersey waterfront, watching worriedly as the fog rolled in, looking at his watch and praying that the rain held off. ‘Every half-hour matters,’ he thought. Williams was so nervous that she had developed blisters, but Mary Wilson, never a great fan of politics, seemed completely unperturbed and spent the afternoon calmly reading the new Oxford Book of Poetry at their hotel. Heavy winds and snow were forecast in the north, yet reports indicated turnout was high: well up, indeed, on 1970.

In the Adelphi, the Labour team ate an early dinner of steak and chips, and Wilson again brought up his elaborate escape plan, which was now ‘too complicated to follow’, with ‘trains and diversionary cars as well as the airplane’. Donoughue was so confused that he lost track of ‘which hotel I am staying in or how I am going back to London if at all’. Wilson seemed a bit chirpier, however, and at 8.30 his young aide accompanied him on a last tour of his Huyton constituency. It was a grim, dreary scene. For two hours, Donoughue recorded, they trudged the streets, ‘in rain and sleet, very dark, totally lost in miles of council house estates’. The party offices and clubs were deserted: most Labour activists were still out canvassing. Reporters and police followed at a distance, but seemed barely interested. Wilson was yesterday’s man. ‘I sensed that everybody saw him as a loser, finished, who could soon be just an old back-bench MP,’ Donoughue noted. ‘At times we walked in the rain, just the two of us, HW and myself, rather lonely figures lost in anonymous wet streets.’ Trying to cheer them both up, Donoughue suggested that it was going to be like the election of 1964, Wilson’s first victory, ‘when we just scraped home. He agreed.’31

At ten the polls closed. Heath was now in Bexley, his constituency for so many years, waiting for the count with his closest allies. In Liverpool, Wilson and his team were huddled around the television in his hotel suite, clutching large glasses of whisky. Marcia Williams was ‘trembling with nerves’; Joe Haines was ‘tense and silent’. Donoughue detected their ‘concern, almost terror, that this will be a repeat of last time’. And then, one by one, the results started coming in. Guildford: a comfortable Tory win. Salford: a boost to Labour’s majority. Wolverhampton North East – Powell country – a swing of 10 per cent to Labour. Just as they had done four years before, the first results were turning all the predictions on their heads. ‘We can’t lose now,’ Donoughue murmured, as though willing himself to believe it. ‘It may be very close, but we won’t lose.’

Close was hardly the word: by midnight, the BBC’s computers were predicting a dead heat. When Wilson left his suite there were suddenly hordes of policemen around him, holding the doors, watching the stairs, ushering him into the lift. Downstairs, Donoughue noted, ‘the press is bubbling and crowd around him and wish him good luck. They know he might win and suddenly the police care and the press change sides.’ At the count, Mary Wilson and Marcia Williams uncorked a bottle of champagne. And at Huyton Labour Club afterwards, the room erupted with screams of delight when Wilson walked in. ‘Everybody singing and chanting,’ Donoughue wrote. ‘Packed. Woman next to me had tears streaming down her face and was shouting, “I love him, I love him.” ’32

Hundreds of miles to the south, the mood was very different. When Heath arrived for his Bexley count just after midnight, his face seemed pale and taut, his smile forced, his eyes glassy. After his result had been confirmed, he confined himself to a few bland remarks of thanks and was then whisked away to his car. Back in Downing Street, he stared at the television in silent disbelief as the results continued to flow in, like a man in deep shock. He had got it all wrong, he told his friend Lord Aldington, and silently the tears of self-pity streamed down his face. But not all Conservatives felt similarly heartbroken. Enoch Powell declined to watch the results, but spent the evening at his London home with his wife and children. The next morning, when he went down at seven o’clock to collect The Times from the letterbox, the headline stared up at him: ‘Mr Heath’s General Election Gamble Fails’. For Powell, it was the sweetest of moments. He went straight back upstairs, ran himself a bath and loudly sang the ‘Te Deum’. ‘I had had my revenge’, he said later, ‘on the man who had destroyed the self-government of the United Kingdom.’33

The result of the election was both extraordinarily close and bewilderingly inconclusive. In terms of the total vote, the Conservatives had won 37.9 per cent, Labour had won 37.2 per cent, the Liberals won 19.3 per cent and the various nationalist parties won the remaining 5 per cent. But the picture in terms of seats was much more complicated. Labour was the biggest party, with 301 seats but no overall majority, the Tories had 297 seats, and the Liberals, punished by the electoral system, had just 14. In Wales, Plaid Cymru did less well than they had hoped, their share falling to just over 10 per cent even though they won two seats. In Scotland, however, the Scottish Nationalists were delighted with their haul, picking up 22 per cent of the vote and six new seats to add to the one they already had. And in Northern Ireland, the results were a devastating blow not just to the cause of power sharing but to Heath’s chances of holding onto power, as the pro-government Unionists were completely blown away and replaced by anti-Heath hardliners under the aegis of the United Ulster Unionist Council. And if anyone doubted that the old two-party system was in deep decay, here was the proof. Both the Conservatives and Labour had suffered blows unprecedented in their history, the Tory vote collapsing by 8 per cent and Labour’s by 6 per cent. Never again would the two major parties command nine-tenths of the vote; from February 1974 onwards, at least one in four people would choose to cast their votes elsewhere.34

For the Conservatives, the results naturally seemed a disaster. No government had suffered a bigger electoral collapse since 1945, and what was particularly disturbing was that the party seemed to have lost touch with its core affluent middle-class voters, 16 per cent of whom had defected to the Liberals. The biggest regional collapse, predictably enough, had come in the Black Country, where the Powell effect saw a swing to Labour of between 5 and 10 per cent, well above the national average. (In Wolverhampton, the swing was even bigger, a massive 12 per cent.) Yet there was an obvious silver lining for Tory supporters. Although Labour crowed that they had won the election, their electoral performance had been almost as poor. Their biggest gains had come among the middle classes – teachers, lecturers, clerical workers and so on – but they had lost votes among manual workers and even trade union households. Indeed, far from improving since 1970, Labour had actually lost half a million votes, the worst performance by an opposition party in modern times. There was certainly no mandate for Labour’s policies: exit polls showed that only a minority of the electorate supported its commitments to more nationalization, the repeal of the incomes policy and the abolition of the industrial relations apparatus. Indeed, 71 per cent told pollsters that they were disappointed with the election results, and only 34 per cent had any faith that a Labour government could succeed. It was hardly a vote of confidence. Yet one of the biggest mistakes Labour ever made was to treat the February 1974 election as a great victory, and to ignore the deeper reality that it was steadily haemorrhaging support.35

The day after the election, Heath cut a very disconsolate figure. With the results so close, he still had a tiny chance of remaining as Prime Minister, but as he dined with friends on Friday night he seemed ‘shell-shocked’, barely seeming to notice as he shovelled down two dozen oysters they had ordered from his beloved Prunier’s. Many people thought he had only himself to blame: Douglas Hurd believed that if Heath had only called the election earlier, for 7 February rather than 28 February, then they would have won. But there is no evidence that any date would have given him the majority he needed, and even if he had scraped home on the 7th, a narrow victory would have solved nothing. Looking back, many senior Conservatives thought that they should have settled with the miners after all, taking the TUC’s offer and pleading exceptional circumstances to the public. Months later, Willie Whitelaw told Ronald McIntosh that his great regret was not settling with the miners before Christmas. Even Margaret Thatcher told ITV’s Brian Walden in 1977 that she was ‘sorry’ the government had not followed up the TUC’s ‘very responsible proposal’ on 9 January. Given her legendary loathing for Heathite appeasement, it is surprising to think that she would have taken the deal and ducked the confrontation. But then Mrs Thatcher was always much more flexible than her reputation suggests – and unlike Heath, she never lost sight of her political self-interest.36

For Harold Wilson, the night of 28 February should have been one to remember, a night of champagne, laughter and sweet satisfaction. In fact, he spent the hours after his count scuttling off to his bolt-hole in Kirkby: ‘a small, miserable hotel’, Donoughue recalled, ‘with poky modern rooms and no atmosphere whatsoever’. Even the receptionist was surly and unfriendly: ‘clearly Tory’, Donoughue thought, although given the standards of hotel service in the mid-1970s, she probably thought she was treating them like honoured guests. In any case, since Wilson had defied the odds, the fact that he was still going through with his convoluted escape plan seemed utterly preposterous, especially as the press soon found out where he was and started shouting and clamouring downstairs. ‘What are we doing here?’ Donoughue wondered. ‘We are winning, not losing … Unhappy to be at this dismal hotel. No place to celebrate a marvellous victory. We should be at the Adelphi, with the Labour crowds celebrating, putting up two fingers to the press. This is wrong.’ But as even he admitted, they could hardly go back there now: ‘That would be too bizarre, to run away from two hotels in one night.’

On Friday morning, Wilson’s party flew back to London. Rain and sleet were pouring down, but Donoughue felt that they all shared ‘the feeling of a job well done’. Only Mary Wilson seemed less than delighted: as the plane descended towards the capital, she remarked that she was not looking forward to life back in Number 10, and would have preferred a quiet retirement with the family. When they landed, however, it was still not clear that she was going to Downing Street. Nobody seemed to have the latest results, and when Donoughue rang Transport House from Heathrow, he was amazed to find that ‘nobody there seemed to know, or was particularly interested to help their party leader find out’. In the end, he had to get the results by phoning the Daily Mirror, who told him that Labour were clearly going to be the biggest single party, but that an overall majority was touch and go. There was nothing to do but wait; if Heath could stitch together a coalition, they might yet be denied the prize. And so they waited, killing time at Wilson’s house in Lord North Street, their elation turning into tiredness and irritability. Morning became afternoon; afternoon stretched into evening. In public, Wilson presented a calm, unruffled front. In private, he was weary and ill-tempered, snapping at his aides, even ringing Jim Callaghan and asking him to issue a statement that they were being cheated. Callaghan refused. ‘We are all tired,’ said Marcia Williams, announcing that she was off to bed.37

The constitutional picture was intensely complicated. Was the Queen morally obliged to invite Wilson, as the leader of the single biggest party, to form the next government? Or should she allow Heath, as the incumbent Prime Minister, to try to form a government with the Liberals, sending for somebody else only if he failed? ‘The Queen could only await events,’ was the message from her Private Secretary, Sir Martin Charteris, on Friday morning. ‘She would not be called upon to take action unless and until Mr Heath tendered his resignation, and if and when he did so it would then be her duty to send for Mr Wilson.’ This gave Heath one last chance to hang on to office. As he admitted to his Principal Private Secretary, Robert Armstrong, it was bound to invite accusations that he was a bad loser, clinging on to power by his fingertips. But Heath was nothing if not stubborn, and, as he saw it, there was a happy coincidence between his personal self-interest and the well-being of the nation. A Labour government, Armstrong recorded, would be committed to such big spending increases that it would put the nation’s economic recovery in severe jeopardy, and it was much ‘less likely to command the degree of confidence overseas which would be required if the sterling exchange rate was to be held and the expected balance of payments deficit financed’. And when Heath’s Cabinet met at six on Friday afternoon, tired and miserable after the shock of the night’s results, they agreed that they should at least try to strike a deal with the Liberals, on the grounds that ‘there was a large anti-Socialist majority which supported both an incomes policy and Britain’s continued membership of the European Community’. Late that night, Armstrong telephoned Jeremy Thorpe and asked him to come to London.38

Britain awoke on Saturday morning to a situation of utter deadlock and confusion. Outside Downing Street, radical demonstrators gathered to chant for Heath’s resignation, led by a group of International Socialists and the freelance protester Tariq Ali. A few minutes’ walk away, Wilson’s Georgian terraced house on Lord North Street stood silent and empty. Yielding to his advisers’ suggestions, the Labour leader had decamped to his farmhouse at Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire, where he presented a typically confident and jaunty image, kicking a ball about in the cool spring sunshine with Paddy, his gigantic Labrador. Behind the scenes, however, Wilson was not relaxed at all: indeed, he phoned Bernard Donoughue several times to vent his fury that the Liberals were going to snatch victory away from him. In his darker moments, he even fantasized about striking directly at Jeremy Thorpe, whose murky involvement with the stable boy Norman Scott had come to the attention of MI5 – and therefore to the government – during the 1960s. Wisely, however, Wilson held back from using this ultimate weapon, and simply waited for events to play themselves out. And by the time Barbara Castle rang for a chat on Sunday morning, he was in much better spirits, joking about the strange situation and mulling over his plans for the new Cabinet. There would be ‘no more of those off the record discussions of what the Government is going to do’, he told her; he wanted a calmer, wiser, less hysterical government this time. ‘Some of his old spirit seems to have come back,’ she noted afterwards. ‘Certainly Harold is the only man for this tricky hour. It could be that he has really learned the lessons of last time.’39

Behind Wilson’s good cheer lay the fact that a Conservative–Liberal coalition was now looking distinctly unlikely. Early on Saturday morning, Thorpe had slipped out of his North Devon home, wearing a country coat and wellington boots over his characteristically dapper dark suit. He trudged across three damp fields to a neighbouring farm, and from there drove to Taunton station, hoping to escape press scrutiny. He did not make it to Downing Street until four that afternoon, when Armstrong smuggled him past the demonstrators through the Foreign Office and the steps from St James’s Park. But while Thorpe’s talks with Heath were ‘friendly and easy’, Armstrong recorded, there was no great breakthrough. Although Heath was willing to contemplate a ‘high level inquiry’ on electoral reform, Thorpe pointed out that Liberal activists would want something rather more concrete – especially as they were seething at the injustice of having won almost 20 per cent of the vote but only fourteen seats. And although Thorpe was naturally excited at the thought of becoming a political kingmaker and perhaps even sitting in the Cabinet as Home Secretary, he was well aware that many Liberals loathed Heath and would be furious at the prospect of saving his bacon. Indeed, within hours of Thorpe leaving Downing Street, he rang his friend Nigel Fisher, a Tory MP, and told him that he was already ‘encountering a rather embarrassing problem with his colleagues about the Prime Minister personally. They feel they could not agree to serve as long as he is the Prime Minister.’ On top of that, ‘there could be no deal’ without a commitment to electoral reform within six months, which Heath could never give without alienating his own backbenchers. And that, in essence, was the end of that.40

Thorpe did not put Heath out of his misery until Monday afternoon, when he had finished his soundings among his Liberal colleagues. ‘I am sorry, this is obviously hell – a nightmare on stilts for you,’ Thorpe told him on the phone on Sunday night, adding that if it were left to him, he would love to ‘work something out’. But when Heath summoned his Cabinet on Monday morning, it was painfully obvious that there was nothing to discuss. As they all agreed, the economic situation was so desperate that only a secure, stable government could sort it out – which meant a formal coalition with the Liberals, and that was clearly not on the agenda. In any case, ministers reported that Tory backbenchers were ‘increasingly worried by talk of a deal with the Liberals over proportional representation’. To all intents and purposes, the game was up. ‘From now on,’ Robert Armstrong recorded, ‘it was probably only a matter of hours before the Prime Minister resigned.’ In the Cabinet Room he organized an impromptu champagne farewell for Heath’s chief civil servants, including the now recovered Sir William Armstrong, but the Prime Minister was in no mood for sentimental partings. ‘It was not a cheerful occasion,’ Armstrong noted, and a few hours later Heath confessed that ‘he felt worn out’. Late that afternoon, the Liberals definitively rejected his offer. His premiership was over.41

Heath had been Prime Minister for three years and 259 days, although his period in office was packed with so many crises that he seemed to have been there for a decade. By conventional standards, his government had been a total failure. When elected, he had promised to revive the British economy, yet unemployment broke through the one million mark for the first time since the 1930s, inflation began to surge into double figures, the money supply ran disastrously out of control, government borrowing rose to record levels and the balance of payments deficit – which had played a key part in his rise to power – reached an unprecedented £380 million. He had promised to revitalize the nation’s industry, yet by 1974 Britain was mocked abroad as the Sick Man of Europe, its travails epitomized by the humiliating collapse of Rolls-Royce. He had promised to rekindle the values of competition and free enterprise, yet he threw millions of pounds of taxpayers’ money not only at Rolls-Royce but also at Upper Clyde Shipbuilders, in clear defiance of his experts’ advice. He had promised to let the free market govern wages and prices, yet he left office having set up a gargantuan apparatus of Pay Boards and Price Commissions that appalled many of his own supporters. He had promised to reform industrial relations on clean, rational lines, yet he presided over the most debilitating industrial conflicts in living memory and saw his government twice humiliated by the miners. He had promised ‘not to divide but to unite’, yet he left office loathed by many of his own people, who saw him as a cruel, confrontational reactionary. And he had promised ‘to create one nation’, yet he presided over some of the most savage civil conflict in the history of the United Kingdom, with blood on the streets of Belfast and bombs in the streets of London.

Yet much of the conventional wisdom about the Heath government is simply wrong. It is not true, as critics on the left claim, that he was bent on confrontation with the unions. In fact, he wanted nothing more than to work in partnership with them, tried to bring them into economic decision-making, and did all he could (as he saw it) to avoid the miners’ dispute that brought him down. And it is not true, as his Thatcherite adversaries insist, that he cravenly abandoned his free-market ‘Selsdon Man’ commitments when the going got tough. It is true that in some ways he anticipated Mrs Thatcher – in his provincial grammar school background, in his emphasis on entrepreneurship, in his impatience with tradition. But he was too much a creature of the system, too deeply marked by the experiences of the Depression and the war, to be a true proto-Thatcherite. His friends Denis Healey and Douglas Hurd – one Labour, one Tory – agreed that the politician he most resembled was Sir Robert Peel, who smashed his own party with the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. Like Peel, Heath was an industrious, earnest, terse and repressed man from outside the magic circle. Like Peel, he was a modernizer, a reformer, a pragmatist who believed that every problem had a rational solution and that reasoned argument could reconcile competing interests to the greater good. Like Peel, he saw further than many of his colleagues: in his case, his European enthusiasm marked him out as a much more visionary politician than most of his contemporaries. But like Peel, he lacked the communication skills, the deftness of touch, the political dexterity and personal charisma to win the nation to his standard and to unite his party around him.42

That Heath had serious flaws as a national leader is surely not in doubt. He was a terrible speaker; he was preposterously rude and grumpy; he was far too impatient; he tried to do too much too quickly; and he was insensitive to the values and pressures that drove other people. It is worth pointing out, however, that he was also incredibly unlucky. No Prime Minister since Ramsay MacDonald had been dealt such a terrible hand: in June 1970, not even the most pessimistic forecaster could possibly have predicted the collapse of the global financial system, the rise of worldwide inflation, the oil shock, the escalation of violence in Northern Ireland, and the wider sense of social breakdown that flowed from the rise in street crime, the explosion of football hooliganism and the controversies over permissiveness, immigration and delinquency. As his friend Jim Prior later wrote, Heath, his government and the institutions of Britain were like a ‘captain, his crew and an ageing ship setting out with new charts on a voyage during which he planned to introduce new disciplines and to refurbish the engine and hull. But what neither Ted nor any of his officers could know was that we were heading for heavy seas.’ It was the worst possible context in which to attempt such a brusque and rapid programme of modernization, and it was Heath who paid the price.43

If his administration was a failure, though, it was not an ignoble one. And although Heath got the date of his re-election bid badly wrong, the fact remains that on many of the big questions he was absolutely right. He was right, for example, to see that Britain’s future as a trading nation lay within the European Community. He was right in his prescription for Northern Ireland; there is a peculiar injustice that his regime is remembered for Bloody Sunday when the Sunningdale agreement so closely anticipated the peace process of the 1990s. He was right to see that Britain’s industrial relations were an anarchic shambles, right to see that its public institutions were complacent and sclerotic, right to see the dangers of rampant wage inflation, and right to see that British industry needed drastic modernization to compete in a globalized world. The irony, though, is that he paid a heavy penalty for being right on so many issues and for his impatience to tackle them all at once. As his biographer remarks, the truth is that the British electorate, fattened by decades of affluence, shrank from the painful changes Heath was offering. When they were offered the chance of a quieter life under good old Mr Wilson, they took it. As Bernard Donoughue, of all people, later admitted, ‘the electorate realised that Heath was right and one day there had to be a battle with the unions to curb their irresponsibilities. But the public was not quite ready for it yet. They were tempted by Wilson’s Labour as the fudge to put off the evil day of battle.’ But that day was coming, all the same.44

Early on the morning of Monday, 4 March, Heath held one last, rather pointless Cabinet meeting, a bleak occasion at which most of his ministers were too tired and depressed even for the usual farewell compliments. Only Margaret Thatcher roused herself to offer an emotional tribute, praising the ‘wonderful experience of team loyalty’ she had shared since 1970 – an extraordinarily ironic moment, given what was to come. Just before six, the Prime Minister bade farewell to the Downing Street staff, having told Robert Armstrong that he did not want to endure the humiliation of returning to collect his grand piano and his manuscripts of music scores after he had formally resigned. It was Armstrong, the fellow musical enthusiast, who replied on behalf of the staff, wishing him ‘good health and better luck’. Upstairs, his aides were frantically stuffing piles of paper into boxes and bin liners, rushing to evacuate the building before their replacements arrived.

And then it was all over, and the two men left for Buckingham Palace. ‘On the drive we neither of us said a word,’ Armstrong recalled. ‘There was so much, or nothing, left to say.’ Even at this last, supremely emotional moment, Heath remained impassive, masking his shock and disappointment behind the familiar granite mask. But for Armstrong, who had become so close to his chief, it was all too much to bear. After Heath had disappeared to see the Queen, Sir Martin Charteris took the young Private Secretary aside and murmured a few words of sympathy. ‘I do not remember what he said,’ Armstrong wrote later, ‘but I remember that I nearly broke into tears when he said it.’45