It was autumn when I returned to the excitements of New York and to the same old problem of making a living.”1 Patrons for portraits were less plentiful due to the worsening economy. There were breadlines, soup kitchens, shanty towns, and political unrest. “The depression is rampant,” he wrote to his father on November 1. “These people seem so tired—having seen the futility of their mad scramble after wealth—they have nothing. The whole place seems an enormous mistake—mostly sham.”2

As he had hoped, Noguchi found a studio on Fifty-seventh Street, and he started to make portraits to pay the rent. Two terra-cotta heads of the great Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco, who was then painting murals at Manhattan’s New School for Social Research, were cast from the same plaster mold. Noguchi may have met Orozco at one of various group shows in which Orozco participated in 1931, or he could have run into him at either the Delphic Studios or the Downtown Gallery, venues where Orozco showed his work. Like Diego Rivera, Orozco was greatly admired by left-leaning Americans. The Mexican muralists’ belief in public art with political and historical content was a model for many American artists during the Depression years. Noguchi’s vigorously modeled portrait with its intense, deep-set, shadowed eyes and tightly closed lips captures much of the painter’s intelligence and intransigence, his bitter irony and his capacity for tenderness and hope.

In 1932 Noguchi made another terra-cotta head, this time a portrait of his fifty-eight-year-old mother. His approach was straightforward—no gimmicks, no stylization, just the aging face of a wise and persevering woman. Her expression seems wistful, yet there is about her full mouth the hint of a smile, a smile that makes one think of Leonie’s habit of making light of hardships. Perhaps there is in this portrait a touch of pity, too—Noguchi’s sadness when he considered his mother’s life, which had on the whole been a disappointment. She continued to scratch out a living by selling Japanese objects and by publishing the occasional magazine article.3 Noguchi’s portrait of Leonie reveals his deep attachment to her in spite of the fact that he sometimes chafed under her motherly intrusions.

Two of Noguchi’s 1932 portraits were of prominent men in the art world. One was of his old friend the art dealer J. B. Neumann and the other was of the New Yorker art critic Murdock Pemberton. Neumann, then forty-five years old, most likely commissioned his portrait to help Noguchi. The sitter’s eyes appear to gaze upward like some saint transfixed by a celestial vision. When this portrait was shown in December 1932 at the Reinhardt Gallery, the Art News reviewer said that the “cherubic and puffy” Neumann looked “as if he had just swallowed a couple of dozen larks and was about to go coloratura on us.”4 Murdock Pemberton, on the other hand, looks downward, his mouth tensed in concentration, his large forehead suggesting intellectual authority.

Possibly in anticipation of his 1932 show at the Reinhardt Gallery, Noguchi decided to vary his approach to portraiture. He began to carve in wood, in a style more modern. Among his well-connected portrait subjects was Suzanne Ziegler, a writer and a copy editor for Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, and House and Garden. Noguchi first modeled Zeigler’s face in clay and then carved two versions of the portrait in wood. The version that he sold to Ziegler is smoothly finished and whitewashed so that she looks ghostly. The version he kept is rougher and unpainted and the top of the head is cut off in a manner that departs radically from verisimilitude. Apparently she did not like either version and would have destroyed the portrait she owned had not her husband intervened.5

One of the beautiful women whom Noguchi encouraged to sit for him in 1932 was the socialite and aspiring actress Dorothy Hale, with whom he had a love affair early the following year. In a 1965 letter to Noguchi his friend Kay Halle recalled what might have been an act of courtship: after dining with Halle and Hale, Noguchi sculpted a “wonderful phallus” as a gift for Hale.6 The two went on a Caribbean cruise, and she accompanied him to London and Paris in June 1933. “She was a very beautiful girl,” Noguchi recalled. “All of my girls are beautiful.” Though the romance seems to have petered out, they remained friends until her suicide in 1938. “Bucky and I were there the night before she did it. I remember very well, she said, ‘Well, that’s the end of the vodka. There isn’t any more.’ Just like that, you know. I wouldn’t have thought of it much, except afterward I realized that that’s what she was talking about. Dorothy was very pretty, and she traveled in this false world. She didn’t want to be second to anybody, and she must have thought she was slipping.”7 That night Noguchi gave her a corsage of yellow roses. Unhappy in love and disappointed in her acting career, she jumped from a high window of Hampshire House on Central Park South, an event recorded in one of Frida Kahlo’s most dramatic portraits. Pinned to the black evening gown she had worn that final evening was Noguchi’s rose corsage.

Another lovely woman to sit for Noguchi in 1932 was the actress Agna Enters. Her almond-shaped eyes may have been influenced by Picasso’s portrait of Gertrude Stein. When the bronze cast was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum in 1934, the museum’s bulletin recorded the acquisition and commended Noguchi’s “ability to achieve accurate and sympathetic characterizations in a simple and direct manner.”8 It was not Noguchi’s first museum attention; in November 1932 he sold his 1929 portrait of the waitress Ruth Parks to the Whitney Museum, and that same year he exhibited his portrait of Uncle Takagi at the Museum of Modern Art.

Noguchi had four exhibitions in 1932, three in New York and one in Chicago. In February he had two shows at once on two floors of the spacious Demotte Galleries at 25 East Seventy-eighth Street. Upstairs were the life drawings of nudes done in Paris and downstairs were the scrolls made in Peking. The other show, at the John Becker Gallery, included sculptures in terra-cotta, plaster, and bronze, as well as a few portraits. Reviews mention a sculpture called Bird, which must be Peking Duck, originally made in plaster while Noguchi was in China.

Also in the Becker show was Erai Yatcha Hoi (Kintaro), a ceramic figure that Noguchi made in Kyoto. One newspaper reviewer gave a loose translation of the title: “What a great guy I am!”9 Noguchi added the name “Kintaro” to the sculpture’s title when he reproduced it in his autobiography. Kintaro was a miraculous child born out of a peach in a famous Japanese fairy tale, and Noguchi’s plump male figure standing in a ritualistic fight posture has the same delicate primitivism (seemingly derived from Tang figurines) as Peking Duck. Perhaps he is a sumo wrestler challenging an opponent before a match, or perhaps the figure records the moment when Kintaro confronts and vanquishes a legendary monster.

Although not much sold at these exhibitions, reviews were mostly favorable. Many critics noted Noguchi’s virtuosity, his range of modes, his rising fame, and his Japaneseness. The exception was Henry McBride, the highly respected critic for The Sun (New York), who wrote a snide review that must have felt like a slap in the face to Noguchi. McBride saw Noguchi as an Oriental with highly suspect aspirations toward Western cosmopolitanism. (McBride had the misapprehension that Noguchi had been born in Japan and had come to the United States as a child.) Noguchi, he said, “prefers now to have his art regarded as Occidental. It will be difficult to persuade the public to this opinion, however. Once an Oriental always an Oriental, it appears.”10 Many reviewers emphasized Noguchi’s blending of East and West. The New Yorker, for example, said: “Noguchi is torn between the classic forms of the Orient and the modern tendencies of the New World … He is certainly one of the more brilliant of the younger men.”11 The New York Times found Noguchi’s sculpture “compellingly beautiful.”12

Noguchi once said that his 1932 exhibitions received more attention than any of his future shows. The Chicago Arts Club show comprising fifteen of the Chinese brush drawings and twenty portraits opened in late March and then toured some twenty West Coast museums and went on to Honolulu. The Evening Post’s critic was amazed at Noguchi’s power as a draftsman and his “remarkable sense of just where to put his subject” on the sheet of paper. She saw in the drawings a “quietude” and a “strength without insistence on strength.”13

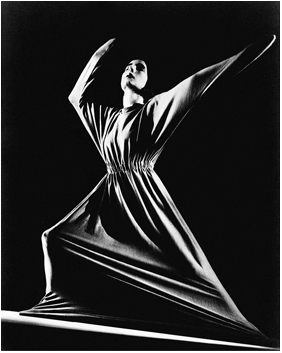

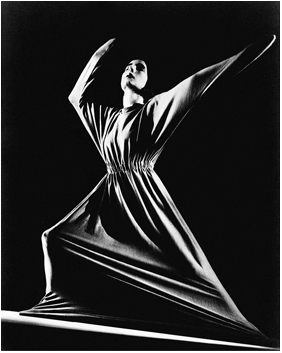

While in Chicago for his openings, Noguchi made two portraits, one of composer John Alden Carpenter and one of novelist and playwright Thornton Wilder. In its simplicity and serenity Noguchi’s portrait of Wilder recalls Japanese portraits of Buddhist priests. Noguchi lingered in Chicago in part because he wanted to avoid his Manhattan creditors (he wrote to his mother asking her to make sure his studio there had not been sublet), but also because he had fallen in love with a beautiful, dark-haired dancer and choreographer named Ruth Page whom he had met at an Arts Club concert. The daughter of a brain surgeon and a pianist and the wife of a prominent lawyer, Page was known for creating ballets with American themes and for combining classical ballet with movement from sports, popular dancing, and everyday gestures. Noguchi bombarded Page with love letters and asked her to pose for him. Although her marriage was not unhappy, she felt that Noguchi was a soul mate. “I was crazy about Noguchi,” she recalled. “But in a funny kind of way. I don’t know what kind of way it was … He was one of the most beautiful men you have ever seen … He had a sort of lost, faraway look that was irresistible; very penetrating eyes that looked right into your soul”14 Page came close to divorcing her husband so that she could marry Noguchi: “He wanted me to but I don’t know … he had so many women, you know. I would have been just one among many.” The affair went on for about a year, after which they remained friends. In the 1940s Noguchi designed costumes and a set for her dance The Bells.

Ruth Page in Noguchi’s first sack dress, 1932

* * *

Leonie’s April letter to her son said that she had gone to his studio and found an eviction notice on the door. There was a claim for $210 in rent. When she gathered his mail to forward it to him, she found a number of telephone and electric bills, and soon his telephone service was cut off.

Upon his return to New York, Noguchi was indeed evicted from his studio. His work was seized by a sheriff who turned out to be an American Indian who empathized with Noguchi and suggested that Noguchi just hand over the drawings that he didn’t particularly want. “I took refuge in a vacant store on East 76th Street and moved eventually to a fancier place, having acquired fancy friends, to the Hotel Des Artistes.”15 At one point, probably in late 1932, Noguchi shared an apartment with the entrepreneur Sidney Spivak and his friend Paul Nitze (who eventually became U.S. secretary of the navy). In lieu of paying rent, Noguchi made portraits of Spivak and Nitze as well as one of Spivak’s girlfriends (and later wife) Dorothy Dillon. Looking at his portrait years later, Nitze remembered that Noguchi was “fed up with it, so he whacked it with a 2-by-4.”16

In this period, Noguchi and Buckminster Fuller sometimes slept on sofas in various friends’ apartments. Endowed with the aura of confidence of the wellborn, Fuller was able to convince the Carlyle Hotel to let him and Noguchi use rooms that were unoccupied thanks to the Depression. As Noguchi recalled: “We would move in with our air mattresses and a drawing board and that was it. The less the better was his credo.”17

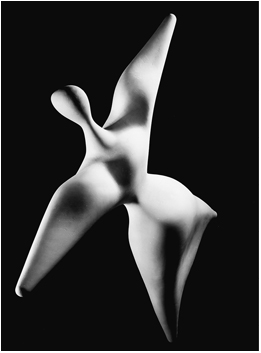

After Noguchi found a studio, he embarked on Miss Expanding Universe, a thirty-inch-long, semiabstract, floating female figure that was inspired by Ruth Page’s dancing and was given its title by Fuller. Modeled in plaster and later cast in aluminum, Miss Expanding Universe was to be suspended from the ceiling and thus seen from below like some levitating vision. With her flowing curves and pneumatic volumes the sculpture brings to mind the free forms of Jean Arp. Her head is but a featureless round peg, very like the vestigial heads of women in so many contemporaneous Surrealist images. Indeed, her shape recalls the biomorphic shapes in Noguchi’s friend Arshile Gorky’s drawings from the early 1930s, especially Gorky’s ink studies for his Khorkom series. Her outstretched arms and legs are encased in a close-fitting skirt. The costume must be Noguchi’s response to watching Page dance in a sack made of flexible knit fabric that he designed for her to wear in her dance titled Expanding Universe.

When Miss Expanding Universe was hung in Noguchi’s Reinhardt Gallery show, Julien Levy felt ambivalent about what he saw as a turn toward semiabstract form: “These new figures seem only half-realized, amorphous,” he wrote.18 He wondered if Noguchi’s mixed parentage had contributed to “a certain ‘bi-polarity’ of attitude which characterizes his work. He is always attempting a nice balance between the abstract and the concrete, the relating of fact to meaning, while specifically he exercises a vigorous interpretation of oriental and western aims.”19

Miss Expanding Universe, 1932. Plaster, 407⁄8 × 347⁄8 in.

Noguchi told a Time reporter that “to me, at least, Miss Expanding Universe is full of hope.” This, he said, was by contrast with the “bitterness [and] hopelessness of so much modern art.”20 Time’s reporter called Miss Expanding Universe “a great white plaster shape, something like a starfish and something like a woman.” Edward Alden Jewell wrote in The New York Times that he admired Noguchi’s more abstract sculptures, but that Miss Expanding Universe “might strike you as resembling a sublimated scarecrow going through setting-up exercises in conjunction with one of the early morning radio health programs.”21 Jewell preferred The Flutter, Noguchi’s eighteen-inch-high chromium-plated bronze abstraction symbolizing the “grace of femininity,” which had recently been installed over the door of the women’s lounge in the new RKO Roxy Theater in Radio City.

Henry McBride was kinder to the Reinhardt show than he had been to Noguchi’s two February exhibitions. He said that Noguchi’s talent for drawing “wins him credence among connoisseurs for his more sensational exploits … There is no artist among us at present whose works differ so much from each other as do those of Noguchi.”22 Noguchi would always refuse to settle into one mode. He did not want to be pigeonholed. “I don’t think I have any style,” he told art critic John Gruen in 1968. “I’m suspicious of the whole business of style because—again it’s a form of inhibition—the more I change, the more I’m me, the new me of that new time.”23

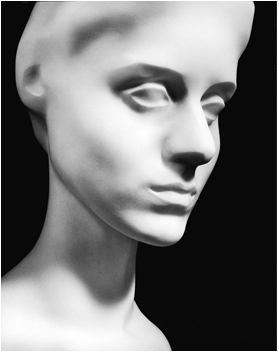

In 1933 Noguchi began to carve portraits in stone as well as in wood. His first was the highly refined, coolly classical white marble head of Clare Boothe Brokaw (later Clare Boothe Luce). The choice of white marble was just right. Brokaw, a slender, blond, blue-eyed beauty with chiseled features, was often compared to a Dresden doll. But a sharp intelligence and steely strength lay beneath the fragile, feminine exterior. With its bold, straight-on glance and its sensuous but firm mouth, Noguchi’s portrait gave her just the right mixture of fortitude and delicacy.

Noguchi most likely met Clare Boothe Brokaw through Dorothy Hale or Buckminster Fuller. Before becoming Vanity Fair’s managing editor, Brokaw wrote the magazine’s “Hall of Fame” column and thus knew everyone in the worlds of art and literature. She married Henry R. Luce, publisher of Time, Fortune, and later Life, in 1935. Noguchi remained friends with her for many years. Legend has it that when she had a nose job she called Noguchi and asked him to adjust the nose of her 1933 portrait to make it resemble her new, improved nose. Noguchi maintained that he remembered the story of what Michelangelo did under similar circumstances: he pretended to chip away at the marble while letting a handful of marble dust trickle through his fingers.

Clare Boothe Brokaw, 1933. Marble, 14 × 9 in.