By 1933 Noguchi was a well-known portraitist with many friends in the worlds of art and privilege. “Portraits were a gregariousness,” he wrote in his autobiography. “By now I was carving them directly in the hardest woods such as lignum vitae and ebony.”1 But, as in 1930 when he took off for Asia, Noguchi was restless. He wanted, he said, to break out of the “constricting category” of portraiture.2

Although Noguchi enjoyed the high life as he courted rich patrons, he also witnessed the misery and humiliation of breadlines and tent communities in Central Park. Like many other artists and writers in the 1930s, he became politicized: “These contrasts of poverty and relative luxury made me more and more conscious of social injustice, and I soon had friends on the Left. But Left or Right, it was a communion with people that I was interested in.” He wanted to find a way to make abstract sculpture, “but I wanted other means of communication—to find a way of sculpture that was humanly meaningful without being realistic, at once abstract and socially relevant … My thoughts were born in despair, seeking stars in the night.”3

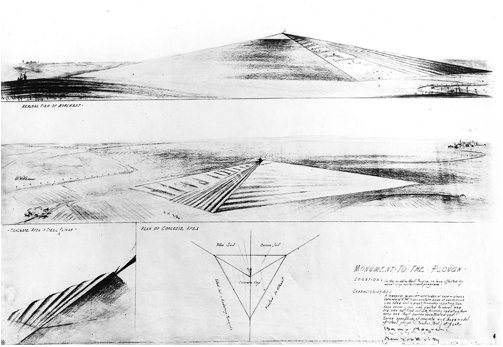

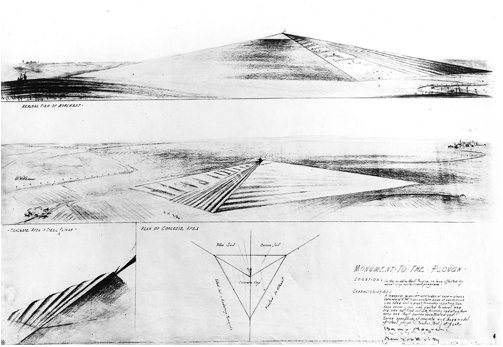

Noguchi was determined to make sculpture part of lived experience, a shaping of a space: “In my efforts to go beyond what I then considered the entrapment of style in modern art and its isolation, I conceived of a Monument to the Plow.”4 This huge earthwork was to be “a triangular pyramid 12,000 feet at base—slopes 8 degrees to 10 degrees to horizontal—made of earth on one side, tilled in furrows radiating from base corner—one side planted to wheat and a third side half tilled soil with furrows radiating from apex and half barren, uncultivated soil.”5 The plow at the top of the pyramid would be a “symbol of agriculture.” Noguchi hoped that Edward Rumely, who had contacts with John Deere, might be able to persuade the company to build his monument. He proposed that it be built “in the middle of the West Prairie,” or somewhere in Oklahoma. “But I was a little ahead of the time.”6

Monument to the Plow, 1933. Pencil drawing, dimensions unknown. Lost

Indeed he was. Four decades later Earthworks would be the most exciting new development in the field of sculpture. Artists like Michael Heizer, Robert Smithson, and Walter de Maria moved tons of earth to create enormous sculptures in remote outdoor spaces in the West. Noguchi’s impetus to make Monument to the Plow was in part motivated by his abiding need to be part of the earth. But he also felt an urge to connect with America’s heritage. This emphasis on American subject matter was widespread in the 1930s, especially after the Federal Art Project got under way in 1933.

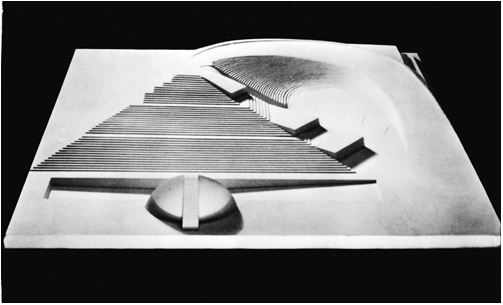

Similarly, his 1933 proposal to build Play Mountain in New York City was impelled by his longing for connection. The playground, he said, was a metaphor for belonging and also a response to his childhood memory of being frightened by a “desolate” playground on a cliff near Tokyo.7

Play Mountain was to be a kind of “rook where you could go both inside and outside.”8 What he did not want was a playground enclosed by chain-link fencing, a “cage, with children in there like animals.”9 Children could climb his Play Mountain and then ride down a water chute. In winter the mountain could be used for sledding, and for summer there was a swimming pool and a bandstand for evening concerts.10 Because it led to other environmental works, Play Mountain was, Noguchi said, “the kernel out of which have grown all my ideas relating sculpture to the earth.”11

A third proposal for a large public sculpture was Monument to Ben Franklin, which was Noguchi’s entry to a 1933 competition that invited sculptors to produce works “emblematical of the history of America.” The tall metal structure resembled the telegraph towers that were beginning to appear on the country’s horizons, and it revealed Noguchi’s admiration for modern engineering feats such as suspension bridges and the airplane—an admiration that was fashionable among artists who liked to say that such inventions were more beautiful than most art. No doubt his friendship with Buckminster Fuller, with whose engineering inventions he was intimately familiar, also had an impact on the design. At the bottom of the monument was a key, above which was an upward thrusting bolt of lightning. On the top was a kite. A model for the monument was shown in Philadelphia in 1934, but the piece was not built until 1984. Indeed, as Noguchi acknowledged, the technology to build such a monument was not available in the mid-1930s. In this fanciful frame of mind, and inspired by his memory of the Peking pigeons to which flutes made of gourds were attached, Noguchi designed Musical Weathervane. “This was to be made of metal, with flutings that would make sounds like those of an Aeolian harp. It was also to be wired so as to be luminous at night.”12

Play Mountain, 1933. Plaster model, 29¼ × 25¾ × 4½ in.

In 1933 Noguchi was also involved with making a plaster model for Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Car, a streamlined vehicle with two wheels in front and one behind. Shaped like a blimp, it was a radical departure from the boxy sedans of the 1930s. The car was to be fuel-efficient and fast—it could go 120 miles per hour. Noguchi enjoyed his collaboration with Fuller: “Your ideas,” he told Fuller, “were an abstraction which I could accept as being part of life and useful.”13

Toward the end of June, accompanied by Dorothy Hale, Noguchi arrived in London, where he was to have a show at the Sydney Burney Gallery.14 On July 9 he wrote to his mother that things were “still unsettled here,” and that he planned to go to Paris the following week “to see how the stone cutting progresses.”15 When he returned to London, he would take a studio for a month and, if he could afford it, he would stay. If not, he would return to the United States. London, he said, “is not easy to get used to. It is expensive and inconvenient—yet undoubtedly there are a surplus of interesting people here once one can reach them … I am always full of expectations.”

In Paris in mid-July Noguchi ordered white marble to make portraits. Back in London around July 25 he wrote to Leonie of his disappointment in Paris. He called it “that infernal place.”16 Indeed, Paris in 1933 was not the exuberant “moveable feast” that it had been in the 1920s. The Depression was as grueling there as it was in the United States, and, after the Nazi party won the election in January 1933, refugees fleeing Germany began to arrive.

It must have been during this Paris sojourn that Julien Levy took Noguchi and Clare Boothe Brokaw to the brothel Le Sphinx. Within minutes of arrival Brokaw turned on Levy in a fury, saying, “How dare you bring us to such a disgusting spectacle?”17 Levy was astonished—Brokaw had asked to see such a place, thinking of it as one of the sights of Paris. Levy retaliated a few months later when he gave a party for the cast of Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson’s Four Saints in Three Acts. When Brokaw arrived, he welcomed her with “Why, Clare, do come in. The last time I saw you was in a whorehouse in Paris.” Noguchi must have arrived at Levy’s party accompanied by Brokaw and Dorothy Hale. With these two friends he traveled in February 1934 through Connecticut in Buckminster Fuller’s Dymaxion Car. After stopping to see Thornton Wilder in Hamden, they joined Fuller in Hartford for the opening of Four Saints in Three Acts.

After some ten days in Paris, Noguchi returned to London and rented Oak Cottage Studio, at Chiswick, a suburb west of London. A transformed barn with no heat or electricity, the studio did offer excellent light. “I have had a great deal of difficulty getting to work over here,” he wrote to Leonie on August 17, “but finally I am at it in this studio.”18 At seven in the evening on Sunday, September 3, he had just stopped working. It was “a beautiful day, and the church bells are ringing—that is the only noise, otherwise utter quiet here by the river. I have never had such relaxation in a long time. All my thoughts and energies and attention are just now most taken up by this statue which I hope to have finished for delivery in New York next month.”19 He said he felt “out of touch with actuality,” and he missed his mother and sister and New York. He enclosed ten dollars, less than he had wanted to send, but all he could afford.

By November, Noguchi was selling some drawings and making plans to return to America, despite his concerns about New York creditors. His letters to Leonie during this time brought no response, and he began to worry. Finally, he boarded the Europa on December 8 and when he arrived in New York on December 17, he learned that his mother had pneumonia and had been admitted to the understaffed and overcrowded Bellevue Hospital on December 12. Leonie died two weeks later at age fifty-nine. Losing his mother was wrenching for Noguchi. He must have felt that he had neglected and in some ways rejected her, in part because he was dependent on her love. In his notes for his autobiography Noguchi wrote: “Mother’s death 1933 added to my unhappiness & confusion—guilt.”20 Leonie left Noguchi a Japanese woodblock print by the Edo-period artist Eizan Kikugawa. It depicted the folktale hero Kintaro. To Ailes, Leonie left a print of a nursing mother by the same artist. Early in the new year Noguchi and Ailes met at a Japanese restaurant called Miyako to honor Leonie. She was buried near her mother Albiana in the family plot in Brooklyn’s Cypress Hills Cemetery. Perhaps thinking of the way that haniwa figures provided company for the dead in ancient Japanese grave mounds, Noguchi put one of his terra-cotta sculptures from Kyoto in her grave. “I never asked my mother about her life. I have never known exactly when she separated from my father. All I know is that my mother loved my father all her life. She gave this love to me. It was my mother also who gave me a love of nature and of things Japanese—my mother and the fact of my being with her in Japan as a child.”21 Another time he said, “Everything I do is in a sense what she might have wished.”22