After his exhilarating months in Mexico, Manhattan depressed Noguchi. “It was the time of civil war in Spain and the United Front. Meetings, resolutions and rallies followed each other.”1 He resumed his efforts to enroll in the WPA program, but was again rejected. This left him out of the camaraderie that developed among artists working for a pittance from the government. The artists met each week in paycheck lines, where they gossiped and held lively discussions about art and politics. Once again Noguchi turned to portraiture to make ends meet. He rented two carpenter’s shacks at 211 East Forty-ninth Street, fixed them up as studios, and sublet one to his friend and fellow sculptor Ahron Ben-Shmuel. Besides making portraits Noguchi entered into every competition he knew of. “I even thought up projects, but all without success. I was willing to do almost anything to get out of my rut—to find the means to practice an art I did not have to sell.”2 Wishing to escape from his role as a fashionable portraitist, Noguchi acted on his growing conviction, first stated in his Marie Harriman exhibition brochure, that “sculpture can be a vital force in our everyday life if projected into communal usefulness.”3 He had made objects that were useful before. When he was twenty he had designed some sugar cake molds. In 1926 he designed a plastic clock called “Measured Time,” and in 1933 he had invented his Musical Weathervane, a mass-producible sculpture.

In 1937 the Zenith Radio Corporation, responding to the anxiety that followed the 1932 kidnapping of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s baby, commissioned Noguchi to make an intercom device, which consisted of a boxlike receiver—the so-called Guardian Ear—to be placed in a child’s or sick person’s bedroom. The other half was the transmitter, a more or less oval, Art Deco–style abstract head made of walnut-colored Bakelite. This could be placed wherever the listening parent might be. Using Noguchi’s “Radio Nurse,” a parent could hear the sound of a baby’s breathing even several rooms away. Looking back on his design, Noguchi wrote in his autobiography: “By a curious switch I thought of commercial art as less contaminated than one that appealed to vanity.”4

His intercom received a lot of attention and its success led to other furniture designs. In 1939 Noguchi designed a coffee table for the new home of A. Conger Goodyear, whose portrait he had sculpted in 1934. The Goodyear table consisted of a free-form glass top supported by two biomorphic shapes. A year later Noguchi redesigned this table for the furniture designer T. H. Robsjohn-Gibbings. According to Noguchi, Robsjohn-Gibbings altered his design slightly and presented the table as his own design in 1942. Noguchi happened to see the Robsjohn-Gibbings variation in an advertisement. “When … I remonstrated, he said anybody could make a three-legged table. In revenge I made my own variant of my own table, articulated as the Goodyear table, but reduced to rudiments.”5 This table was illustrated in George Nelson’s article “How to Make a Table,” and in 1947 the Herman Miller furniture company (where George Nelson was design director) began to manufacture it. Noguchi considered this coffee table to be his most successful venture in the field of industrial design, and it continues to be popular today.

Table for A. Conger Goodyear, 1939. Rosewood, 30 × 84 in.

Perhaps inspired by Buckminster Fuller, and possibly also prompted by his involvement with industrial design, Noguchi became intrigued with the machine as a subject for art. His 1,000 h.p. Heart (1938), a bulbous amalgam of organic and geometric shapes, is part human heart and part aeroengine. For this melding of the machine and human forms, Noguchi seems to have followed the example of the British modernist sculptor Jacob Epstein’s The Rock Drill (1913) and perhaps also the French sculptor Raymond Duchamp-Villon’s Horse (1914), a machine/animal hybrid. 1,000 h.p. Heart conveys a feeling of burgeoning life that also recalls Noguchi’s own 1934 sculpture, Birth.

After his return from Mexico, Noguchi saw a great deal of Arshile Gorky, whom he once said he had first met in 1932 at a gallery.6 The two artists visited museums together and Noguchi listened attentively as Gorky held forth in front of his favorite paintings—paintings that Gorky felt so possessive about that if another visitor had the temerity to stand in front of them, Gorky would glower. “He was very, very well-versed in art history,” Noguchi recalled. “I mean he was a great teacher, among other things, for me anyway.” At the time, Gorky was well known in the art world but his occasional arrogance and frequent scene-stealing annoyed some of his fellow painters. Noguchi told Gorky’s nephew Karlen Mooradian that he and Gorky had a special kinship because they both felt like exiles.7 Both experienced discrimination and both felt a deep attachment to a foreign culture. In fact, although he pretended to be Russian, Gorky was Armenian. Gorky, Noguchi observed, liked to “put on a bit of mystification.”8 His role-playing was in part a way of distancing himself from his traumatic youth—the horrors of the Armenian genocide. Similarly, Noguchi tried to blot out his painful childhood by acting Japanese when the situation called for it and American if that seemed appropriate. Both artists were estranged from their fathers, whom they resented for abandoning their mothers and themselves.

* * *

In 1936 Noguchi joined the newly formed New York Artists’ Union. “I associated myself with the laboring class; with the less fortunate people. And probably it comes from many different sources but I suppose my background of not belonging … had something to do with it.”9 The union, like the WPA, offered artists the camaraderie of penury and politics. Noguchi eventually dropped out of the artists’ union, because, he said, “it was overrun by those interested more in the political angle of attacking the WPA than in art, or the furtherance of art as I saw it.”10 The Spanish Civil War and the rise of fascism brought artists together in support of leftist ideologies and the Spanish Loyalist cause. “I think it took the war really, and Stalin and his coming to terms with Hitler, to really sort of make us diverge from that very fixed and sort of convinced point of view.”11 Indeed, the 1939 Stalin-Hitler pact caused many artists and intellectuals to break with the Communist Party. There was a general feeling of disillusionment and ideological confusion.

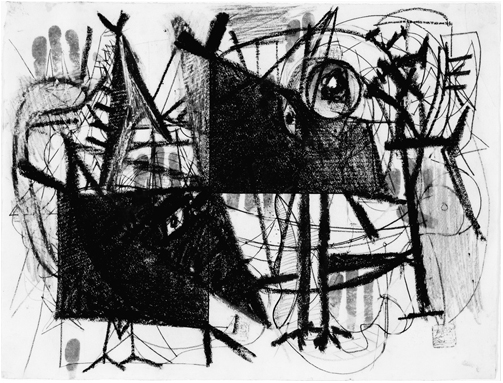

On September 1, 1939, Noguchi, Gorky, and their friend the painter De Hirsh Margules were listening to the radio at Noguchi’s studio when Germany’s invasion of Poland was announced, precipitating the war in Europe. “We made several paintings together at that time,” Noguchi recalled.12 A semiabstract drawing upon which they collaborated reveals the intensity of their alarm. Noguchi apparently drew two large black planes in crayon and Gorky added bird’s legs—a favorite Gorky motif in the late 1930s. By dipping the palms of his hands in red paste, Gorky also made the red handprints that speak of war’s bloodiness. Noguchi used the seal that had been given to him by Ch’i Pai-shih to stamp the paper with the same red paste.13

During this period, Noguchi recalled, various factions sought his support. A Communist group invited him to go to Germany to make a portrait of Hitler and the Japanese consulate in New York asked him to make a statement in support of the Japanese war effort. Noguchi refused. “I avoided any kind of direct involvement,” he said.14 At about the same time the American State Department asked him to send an open letter to his father. Noguchi hesitated and sought the advice of the Chinese ambassador, who said, “Don’t do anything. Don’t attack your father. You’ll regret it.”15

Collaborative drawing by Noguchi, Arshile Gorky, and De Hirsh Margules on the eve of the German invasion of Poland, 1939. Mixed media on paper, 17½ × 227⁄8 in.

Early in December 1937 Noguchi had contributed one of his Peking brush drawings to an auction to raise money for China’s defense held on December 5 at New York’s Park Lane Hotel. Two days before the auction he was interviewed for an article titled “Japanese-American Artist Fears for Old Peiping,” published in the New York World-Telegram. “Japan,” he said, “overcome by a capitalist-militaristic group, has developed a frantic spirit of nationalism … It is tragic that instead of being grateful for all that Chinese culture had given Japan, Japan has set about the methodical business of maiming and slaughtering her people.”16 On December 13 the Japanese Imperial Army began a weeklong siege of China’s capital city and massacred thousands of Nanking’s inhabitants. The so-called Rape of Nanking horrified the American public, and Noguchi was distraught. For years he had been wary of Japanese aggression. Now his fears were realized, and he felt that in some way he shared the Japanese guilt. The New York Times noted that at the auction, Noguchi’s ink wash drawing of a Chinese woman nursing her child had drawn enormous interest and that K. C. Li, a Chinese merchant, had bid seventy dollars for it, and then offered to triple that price if Noguchi would explain publicly why he, as a Japanese-American, had chosen to help the Chinese cause. “I give this drawing as my way of showing the world that not all Japanese are militaristic,” he responded.17 Later in the evening during a raffle for an American-made automobile a little Chinese girl thrust her hand into a glass jar and pulled out a stub. The winning ticket was Noguchi’s.

Noguchi’s auctioned brush drawing has an inscription in Chinese characters that was added to the scroll three months later. It began: “I am a follower of great China and I have learned from its art. Today intruders are attacking the Asian continent, forgetting their cultural roots. I don’t want to forget my art’s teacher.” Noguchi signed the inscription by stamping it with the seal that Ch’i Pai-shih had given him in 1930.18

Noguchi’s sorrow over Japanese aggression was no doubt intensified by the knowledge that his father had become increasingly nationalistic. Yone’s July 1938 letters to Mahatma Gandhi, whom he had met in the 1930s when on a lecture tour in India, and to his old friend the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore defend Japan’s invasion of China as a boon to the impoverished Chinese people and a battle to keep Asia for Asians. “No one can deny the truth in the survival of the fittest,” he wrote to Gandhi. “When I say that the present war is a declaration towards the West to leave hands from Asia, I believe that there are many people in India, who will approve of us.” To Tagore he wrote that “the war is not for conquest, but the correction of mistaken idea of China … Our enemy is only the Kuomintang Government, a miserable puppet of the West.”19

* * *

In fall 1938 Noguchi presented Edsel Ford and the Ford designer Walter D. Teague with a model of his fountain design for the Ford Building at the upcoming New York World’s Fair. He won the job and was paid $1,500 in three installments. Once again he combined machine forms with human anatomy. Just as Gorky in his WPA murals at the Newark airport had built his composition out of abstracted airplane parts, Noguchi created an abstraction based on automobile parts—wheel, chassis, and engine block. The only virtue of the resulting fountain, which Noguchi described as “an engine with chassis rampant!,” was, he said, to teach him the use of magnesite.20 However, after returning from the World’s Fair, Noguchi wrote to Teague that he believed the fountain to be “an artistic success.”21 Noguchi went on to ask for more money—something that in the years to come he would do fairly often. When he felt that he had worked longer or had had greater expenses than stipulated in a contract, he would ask the commissioner for additional payment.

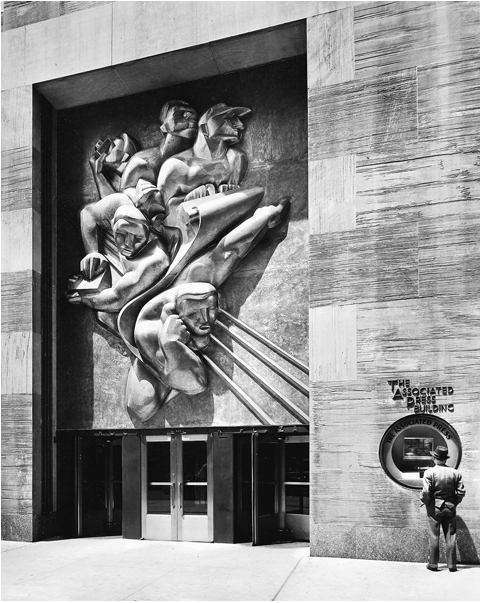

In 1938 Noguchi entered a national competition for a relief panel with imagery symbolic of the American press, to be placed above the door of the new Associated Press Building in Rockefeller Center. There were 188 entries from twenty-six states. The jury included Holger Cahill, the national director of the WPA’s Federal Art Project, and the prominent architect Wallace K. Harrison, who had participated in the construction of Rockefeller Center and was a friend of Nelson Rockefeller. Noguchi submitted two sketch models, one that he had worked on for two months and one that he had dashed off in three days. Years later he said that both models were hangovers from what he called his social realist propagandistic relief mural in Mexico City.22 Indeed, the AP design had much of the market mural’s bombast.

The model that took three days was awarded the prize. “With a sudden surprise, my luck changed, or rather I got my just deserts,” Noguchi recalled in his autobiography. “The real danger of a competition is that one might some day win one. Then there is the time-consuming job of execution—and one is stuck with its reputation.”23 Noguchi received $1,000 in prize money and was to be paid an additional $6,500 for completing the commission. The model had, in the lower right corner, a small figure of a nude man with bent legs and upraised arms. According to The New York Times, this figure symbolized “mankind in the focus of the news.”24 The diagonal lines crossing the plaque’s background were, the Times said, “radiating wires indicating the world-wide network of Associated Press communications.” To my eyes, the nude figure looks more like a shocked recipient of the news than the news’s subject. Noguchi must have been aware of this figure’s awkwardness, for he eliminated it when the plaque went into production.

Noguchi’s ten-ton AP relief sculpture includes five muscular newsmen handling the tools of modern journalism—camera, telephone, wirephoto, teletype, and pad and pencil. Their superman bodies are typical of the heroic males seen in much public art of the Depression years when so many jobless men, unable to support their families, felt diminished. The figures are massed in a compact triangle with its apex thrusting diagonally downward, as if the press, like some angelic messenger, were bringing the news from on high. “The first characteristic of the press,” Noguchi said in a press release, “is vitality. Next, is incisiveness injecting itself into all human activities in quest of truth. I must portray the gathering and disseminating of News, from a vantage point above the tumult.”25 In spite of the stylization of the figures, the plaque does convey the urgency of breaking news.

Although the competition had called for a bronze relief, Noguchi wanted to have his relief, which he first sculpted in plaster, cast in stainless steel, a material that was then used mainly by the automobile industry and for submarines and other military equipment. Noguchi chose it for his AP plaque because it was new and progressive and noncorrosive. It was the only metal other than gold or platinum that would not, the press release pointed out, “foul its own face.” Casting the weighty 20-by-17-foot plaque in stainless steel turned out to be a huge job. “The grinding and welding, together with the plaster enlarging, took over a year of my energy,” Noguchi recalled.26 The relief was divided into nine sections, which were cast and then moved to a different plant where their edges were trimmed to an exact size so that the dividing lines between sections would be invisible, and where the surface was polished with high-speed grinding wheels. At one point Noguchi decided he wanted to reduce reflectivity, so he ground the surface in a variety of angles. An AP news story reported: “The sculptor, Noguchi, worked harder on the plaque than any workman, using the latest power tools, grinding wheels turning at 5000 to 25,000 R.P.M. He personally carved and contoured the finished metal plaque—just as sculptors of old personally finished their metal casts, not only becoming the first sculptor to learn this power tool technique, but studying light refraction and reflection first hand, and working out his contours by light wave measuring devices. Working 16 hours a day through two shifts—holding powerful grinders, Noguchi’s hands were so calloused that he could not make a clenched fist when the job was completed.”27

Associated Press Plaque, 1938–40. Stainless steel casting, 20 × 17 ft. Rockefeller Plaza, New York

In order to move the AP plaque out of the foundry, one of the building’s supporting pillars had to be cut away. Once outside, the piece was power-washed with two hundred gallons of nitric acid and two hundred gallons of ammonia to remove the marks of the iron tools and residual abrasive material. Then it was washed with three thousand gallons of boiling water. Two heavy-duty trucks carried the plaque’s separate sections, each weighing about three tons, to Manhattan, where the pieces were unloaded and rejoined. The plaque, now titled News, was then hoisted by cranes into its place above the entrance to the Associated Press Building. When it was installed, Noguchi climbed the scaffolding and made some final touches with an electric buffing machine.

The unveiling of News at the end of April 1940 was presided over by Nelson Rockefeller, executive vice president of Rockefeller Center, and by Kent Cooper, general manager of the Associated Press. A photograph shows Rockefeller smiling at a smiling Noguchi, who wears pinstripes and carries his fedora. Cooper holds the rope that will remove the cloth that veils the plaque. In his speech Rockefeller said that the relief would “stand forever as a symbol of the freedom of the press.”28

Not everybody was pleased by Noguchi’s vision of American journalism. The New York Herald Tribune viewed the figures of the brawny newsmen as apelike: “There seems to be a suggestion here that news is a roaring, devouring monster—a brute force, unloosing a blitzkrieg at the reader down a stainless steel lightning flash, a naked giant, with a piece of copy paper swathed around his middle, bellowing through the world.”29 Another journalist said of the plaque: “It looks like the cerebellic convolutions of a diseased brain during an autopsy.”30

While Noguchi was hard at work on his AP plaque, Brancusi came to New York for the May 10, 1939, opening of the new home of the Museum of Modern Art, the International Style building designed by Philip Goodwin and Edward Durrell Stone. Noguchi recalled that Brancusi was intrigued with the idea of making a sculpture in stainless steel: “We talked at that time of similarly casting his Endless Column. How unfortunate it was that he insisted on going back to Paris.”31

* * *

After the unveiling of the AP plaque, Noguchi was whisked away and accompanied by a police escort to catch a flight from LaGuardia to San Francisco, where he would board a ship bound for Honolulu. He had been invited by the Hawaiian Pineapple Company to come to Hawaii to work on advertising and on two bas-reliefs incorporating Hawaiian people and subject matter. In addition, he had been offered an exhibition at the Honolulu Academy of Art, which already owned one of Noguchi’s two bronze heads of Martha Graham and—according to the press—a bronze casting of Tsuneko-san. Among other works in the show were the portraits of Buckminster Fuller and George Gershwin; Radio Nurse; Glad Day, the nude equestrian he made in England; Ebony Bird, a sheet metal abstraction; and a model of the swimming pool he designed for Josef von Sternberg. There were also various drawings, models, and some studies for architecture (a column and a capital), which the press said showed “the possibilities for personalization of modern architecture to be developed perhaps in Hawaii.”32 Noguchi told the Honolulu press that people looking at his sculpture could interpret it as they wished. “One cannot express art in so many words or there would not be art … It can mean anything to the person who looks.”33 He concluded his remarks by saying, “To me, my art means a thousand things, and reactions are as many as there are people.”

* * *

Before his trip to Hawaii Noguchi had discussed the possibility of designing a playground for Ala Moana Park with Harry Bent, a Hawaiian architect, and with Lester McCoy, Honolulu’s parks commissioner. When he returned to New York in July, Noguchi made some models for playground equipment that were so beautifully designed they looked like sculptures. Nothing came from the designs in Hawaii, but in October 1940 Architectural Forum featured photographs of his playground designs and a statement from Noguchi: “A multiple length swing,” Noguchi said, “teaches that the rate of swing is determined by the length of the pendulum not by its weight or width of arc … The spiral slide will develop instinct regarding the bank necessary to overcome the centrifugal force developed by the rate of slide.”34 Noguchi, fascinated by the technical aspects of different materials, went on to say that the slide could be made of steel or wood or cupric magnesium oxide covered with latex or cement with slip cement surfacing or possibly weather-resistant plastic. As with Play Mountain, when Noguchi later presented his playground designs to the New York Parks Department he was told that the equipment was too dangerous. (The designs for playground equipment were finally realized in Playscapes, 1976, in Piedmont Park in Atlanta.)

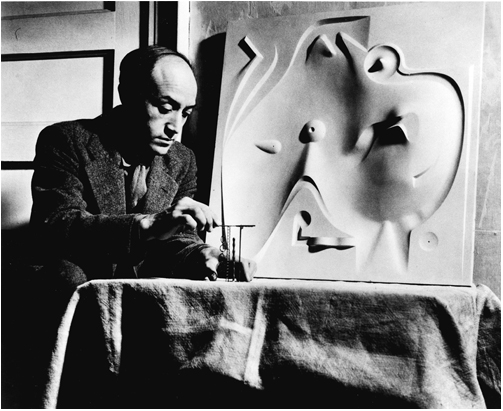

Noguchi with plaster original of Contoured Playground, c. 1946

Noguchi responded with Contoured Playground, “which I conceived to be fail-proof for the simple reason that there was nothing to fall off.”35 It was, he said, “made up entirely of earth modulations. Exercise was to be derived automatically in running up and down the curved surfaces. There were crannies to hide in and mounds to slide down. In Summer water would flow and pool.” The 1941 plaster model, with its soft undulations reminiscent of Miró’s and Gorky’s biomorphism, can be seen as the first of what Noguchi called his tabletop sculptures. Once again his playground proposal came to nothing, this time, he was told, because of the threat of war. “I felt the futility of anything ever happening. It was spring and I decided to move west.” He would look for “new roots” in his native California.