NOGUCHI AND MARTHA GRAHAM, PASSIONATE COLLABORATORS

Even when he insisted in his letters to Ann that he could not focus on work, Noguchi was producing some of his most beautiful sculptures, not only works like Noodle, but also sculptures that he assembled from carved elements. And he had other projects as well. For the Jefferson Memorial competition in St. Louis, Missouri, for example, he proposed an earthwork with geometric and biomorphic concavities and protrusions inspired by his recent visit to the prehistoric Great Serpent Mound in Ohio. Not surprisingly he did not win, but again, this didn’t deter him.

During this time, Noguchi continued to work on sets for Martha Graham. Although his letters to Ann say that he designed for the stage in order to earn money, making sets that functioned as sculptures and that became part of the dancers’ movements clearly fascinated him. His 1935 set for Frontier, in which he carved a large volume of space with two ropes, changed the way he thought about sculpture. In 1940 he designed the set for El Penitente, a dance about the rituals of Christian flagellation in the Southwest, and then in 1944, when the music patron Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge commissioned three dances from Graham and Noguchi designed the sets, he began a collaboration with Graham that lasted until the mid-1960s. Appalachian Spring, with music by Aaron Copland, Hérodiade, with music by Paul Hindemith, and Imagined Wing, with music by Darius Milhaud, were all performed in the fall of 1944 at the Coolidge Auditorium in Washington, D.C., a space designed for chamber music. Just as Japanese gardens are often designed to look larger than they actually are, Noguchi made the small stage appear large. “I tried to create a really new theater with hallucinatory space,” he recalled.1

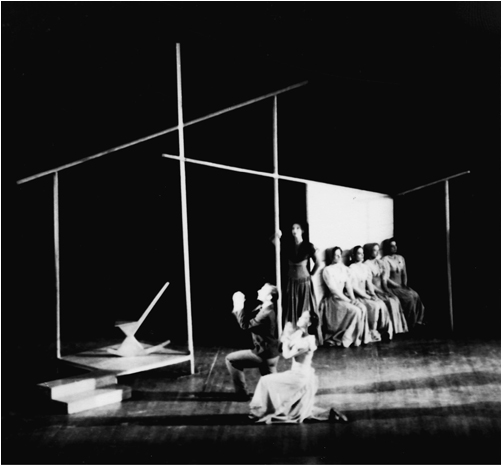

Appalachian Spring, the last of Graham’s dances based on American themes, is about a young pioneering couple taking possession of a newly built house in the mountains of Pennsylvania. “New land, new house, new life; a testament to the American settler, a folk theater,” was Noguchi’s summary.2 His set consisted of a spare structure of wooden poles that stood for the framework of a rudimentary house, a canvas panel painted to look like a clapboard wall, a tree stump, a log fence, and a semiabstract rocking chair placed on a raised area that stood for a porch. “I attempted through the elimination of all non-essentials to arrive at an essence of the stark pioneer spirit, that essence which flows out to permeate the stage. It is empty but full at the same time. It is like Shaker furniture.” Graham recalled that to show Noguchi what she wanted for Appalachian Spring she took him to the Museum of Modern Art to see Giacometti’s 1932 Palace at Four a.m. “He was not very happy about going, but we went. And he understood immediately the quality of space I was looking for.”3

Noguchi’s set for Appalachian Spring, 1944

In Hérodiade, Graham turned from her cycle of dances on the theme of legendary America to dances inspired by Greek mythology and the Bible. This change had much to do with Graham’s Jungian analysis, and her absorption in the writer Joseph Campbell’s theories about myths in different cultures and in different times that shared the same elemental meanings and could potentially guide people to self-knowledge. Starting with Hérodiade, Graham’s dances combined psychological exploration with mythic drama, a turn that suited Noguchi’s mood as well: “I believed in Apollo—all the gods of Olympia long before I knew of any other,” he once said.4 “Everything I have done pertains to myth, from which the truth often emerges, too true to be comfortable.”5 Because Graham transformed classical myths and Bible stories by sending them through her own emotional experience, her dances, always intense, often earnest, and sometimes agonistic, were, Noguchi said, cathartic. “She goes through a kind of ritual each time.”6 Just as Graham’s dances evoked an inner landscape, so Noguchi made the stage into a space of the imagination—a space that alluded to the primal feelings expressed by the dance.

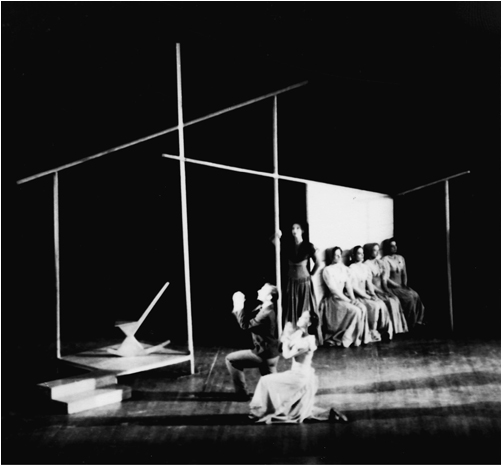

Hérodiade’s nominal subject was Herod and Herodias’s daughter Salome’s confrontation with herself. The dance is a soliloquy about a woman’s journey into her unconscious. The set consisted primarily of painted wooden objects that look very like the biomorphic slotted slab sculptures made of interlocking forms that Noguchi began to make in 1944. These objects were clearly inspired by the free forms seen in the Surrealist paintings of Miró and Yves Tanguy, and in certain Miró-inspired Gorkys. The shapes are bonelike and suggest anatomy, yet in the dance they were also to function as furniture.

The dance itself, which Graham performed at the age of fifty, centers on a woman facing age and her own mortality. “Within a woman’s private world,” Noguchi recalled, “I was able to place a mirror, a chair, and a clothes rack. Salome dances before her mirror. What does she see? Her bones, the potential skeleton of her body. The chair is like an extension of her vertebrae; the clothes rack, the circumscribed bones on which is hung her skin. This is the desecration of beauty, the consciousness of time.”7

The dancer Mary O’Donnell on Noguchi’s set for Hérodiade, 1944

Late in 1945 Noguchi designed two more sets for Graham, one for Dark Meadow and one for Cave of the Heart. When he wrote to Ann about Dark Meadow in November 1945, he said the dance concerned “the voyage of man (woman) in search of his soul. All the symbolisms are there ending up with the Grail (the womb) which renews life. I haven’t got the faintest idea as to how I am to cope with such a grandiose subject matter.” He coped by making four upright, mildly phallic, “primordial” shapes with Miróesque attachments. “They are not stones, but serve the same purpose of suggesting the continuity of time. They move and the world moves.”8

In a December 1945 letter to Ann, Noguchi said Graham had asked him to do the sets for Cave of the Heart: “That’s going to be the real one, the one both of us are really interested in on the theme of Media [sic, he meant Medea].” Medea was, he wrote in a subsequent letter, a victim of destiny. “Is destiny from without or within? A figment of the imagination too?” In Cave of the Heart Medea’s fierce jealousy (prompted by Jason’s abandonment) drives her to kill her and Jason’s children as well as her female rival. The set Noguchi made was simple and dramatic—just a few rocklike forms. “I constructed a landscape like the islands of Greece. On the horizon (center rear) lies a volcanic shape like a black aorta of the heart; to this lead stepping stone islands.”9 These stone islands, inspired by the carefully placed rocks in Zen gardens, allude to Jason’s voyage. Graham recalled that for this set she had made one request: “I said I would love to have a dress which shows the spiritual, the half-goddess quality of Medea, but I don’t want to wear it all the time. I wanted to walk in and out of it.”10 At the end of the dance Medea donned Noguchi’s exquisite construction made of brass wires that, wavering as she moved, suggested the wild flailing of her emotions. As she rose up to join her father, the setting sun, she vanished, but the shining wire dress was left behind like the sunset after the sun goes down.

Collaborating with Graham helped to dispel Noguchi’s loneliness. He had not had an exhibition since 1935 and, while he had many friends among the Surrealists and the future Abstract Expressionists, he felt, as always, like an outsider. With Graham and her dances, on the other hand, he had a passionate connection. In the section on theater and dance in his autobiography he wrote that dancers made his sets come to life: “Then the air becomes charged with meaning and emotion, and form plays its integral part in the re-enactment of a ritual. Theater is a ceremonial; the performance is a rite. Sculpture in daily life should or could be like this.”11

Martha Graham with Noguchi’s set for Cave of the Heart, 1946

Noguchi and Graham’s work together over a period of thirty years was an extraordinary creative dialogue. They understood, respected, and deeply loved each other as artists and as human beings. They were passionate collaborators, not lovers. “Ours was purely, absolutely, a work relationship. I adored him, and I think he adored me. It never entered our minds to have anything except the best, and it never entered our minds to have a love affair. Never.”12 Their mutual empathy made it possible for Noguchi to invent sets that not only enhanced but also propelled Graham’s choreographic invention. She said of working with Noguchi: “A curious intimacy exists between artists in a collaboration. A distant closeness. From the first, there was an unspoken language between Isamu Noguchi and me.”13 Noguchi put it this way: “I contribute to what Martha does. She claims that she has the idea but it is when I supply the setting that she becomes convinced. She says my objects are the things that give her the confidence.”14

Noguchi and Graham both wanted their creations to be simple, poetic, and packed with meaning, but meaning expressed in formal and symbolic ways, never literal. Both were shapers of space, and both were interested in the idea of origins. Noguchi, sounding rather like Graham, wrote, “I thought of sculptures as transfigurations, archetypes, and magical distillations.”15 Graham loved Noguchi’s spare aesthetic: “I realized,” she said, “that everything was stripped to essentials rather than being decorative. Everything he does means something. It is not abstract except if you think of orange juice as the abstraction of an orange. Whatever he did in those sets he did as a Zen garden does it, back to a fundamental of life, of ritual. I forget who said it, but Noguchi illustrates the ‘shock of recognition.’”16

Noguchi’s love for the gardens and temples he had visited in Kyoto informed his dance sets’ economy of form. An important element in both Japanese stroll gardens and Noguchi’s sets was the experience of the body moving through space. The idea of defining space with rope in Frontier may have been inspired by the use of rope (often with fluttering strips of white paper attached) to indicate the sacredness of rocks or trees inhabited by deities (kami) at Shinto shrines. Noguchi’s knowledge of Noh theater, a ritualistic form of drama developed in the fourteenth century, was another source for his spare aesthetic. Gestures and events in Noh theater were full of feeling, but they were always symbolic, referring not to a specific moment but to something universal. The bare stage with just a pine tree painted on the back wall became a landscape of the mind and the minimal props were simply triggers for the spectators’ imagination. Speaking of Noh’s influence on Frontier, Noguchi said that what he valued in Japanese art was that it belonged to “no time and place.”17

Noguchi’s autobiography describes how his and Graham’s collaboration functioned: “In our work together, it is Martha who comes to me with the idea, the theme, the myth upon which the piece is to be based. There are some sections of music perhaps, but usually not. She will tell me if she has any special requirements—whether, for example, she wants a ‘woman’s place.’ The form then is my projection of these ideas. I always work with a scale model of the stage space in my studio. Within it I feel at home and am in command.”18 Some nights he would receive a phone call from Graham: “Usually she called me up in the dead of night and said, ‘Isamu I need your help and I have a wonderful idea and I want to tell you about it.’ I’d go over there and she would go into a story about what she wanted to do … And then I’d go home and I’d give her the setting which would encompass such an emotional topic.”19

Noguchi would appear at Graham’s doorstep with the mockup stage set in a shoebox. Sometimes Graham would ask practical questions such as “Can we really lean on that?” or “What happens if you bump into it?”20 Most often she was delighted. Sometimes she had her doubts. Then she would be gentle, not critical. “I have never said ‘no’ outright to Isamu, because one doesn’t. If you know it won’t work, you become very oriental. In other words I’d say, ‘Well, that is extraordinary. Now I have to think about it overnight.”21 Mostly their collaboration was harmonious, but not surprisingly for two such intense and driven artists, there were disagreements. Takako Asakawa, one of Graham’s dancers, recalled, “Sometimes I would get bumps on my arms because I would see Martha and Noguchi fighting each other, the two of them, because they were so much into what they were doing. ‘Get out of here,’ they would scream. Isamu would come the next day and they would make up. In art, they were like wife and husband.”22 In later years, during periods in which Graham was drinking heavily, she could become physically violent. In her memoir Blood Memory, Graham recalled that on one set, “there was a piece stage right that resembled a curiosity bone. What better symbol for sexuality or fear of it? But as beautiful as this set was, Isamu and I were not in agreement over something or other. This is the only time I can remember being angry with him … I slapped Isamu across the face during dress rehearsal … I suspect I was going through my violent period.”23 But Noguchi’s and Graham’s appreciation for each other was too deep for a permanent rift. Looking back, Noguchi wrote of the privilege of working with Graham: “And to hear her telephone me and say, ‘Now, Isamu,’ was the beginning of many, many happy occasions.”24