THE ROCK AND THE SPACE BETWEEN

Noguchi observed that his set for Hérodiade was closely related to the sculptures that he was beginning to make out of interlocking slotted biomorphic shapes carved from slabs of marble or balsa wood. Indeed, these sculptures, probably his best-loved works, developed right out of the plywood props that he made for Hérodiade. Another precursor was the biomorphic chess table and chess pieces that he designed for the December 1944 Imagery of Chess exhibition at Julien Levy’s Surrealist-oriented gallery.

Noguchi once said that he always used materials that were available at the place where he happened to be working. In the mid-1940s, East Side marble yards were being closed to make way for urban renewal, and the slabs of marble used for surfacing buildings were plentiful and cheap. Noguchi found this marble beautiful. “The nature of its stability is crystalline, like its beauty. It must be approached in terms of absolutes; it can be broken, but not otherwise changed … I took particular satisfaction in its fragility, arguing the essential impermanence of life…”1 In its fragility marble was, Noguchi said, like cherry blossoms. It was “hostage to time, permanent and impermanent. The attraction worried me, trapped in contradictions.”2

In calculating weights and balances, what he called “the forces that conspire to hold up the figure,” Noguchi used his knowledge of engineering: “Everything I do has an element of engineering in it—particularly since I dislike gluing parts together or taking advantage of something that is not inherent in the material. I’m leery of welding or pasting. It implies taking unfair advantage of nature.”3 Each interlocking slab sculpture was assembled from about eight separate pieces fitted together by slots cut into their edges. Like traditional Japanese houses, they were constructed without screws or nails. Noguchi recalled that when he made these sculptures he was “entranced by lightness and hanging.” His carefully balanced shapes, his play with gravity, and the sculptures’ feeling of suspension bring to mind the contemporaneous mobiles of his friend Sandy Calder, whose success always made Noguchi envious.

Noguchi in MacDougal Alley courtyard with Strange Bird, 1945.

Noguchi’s interlocking slab sculptures can be seen as a kind of “drawing in space,” a phrase most often used to describe David Smith’s openwork welded metal sculptures. Noguchi intended the spaces between his forms to be seen as positive shapes. He wrote in 1949: “If sculpture is the rock, it is also the space between rocks and between the rock and a man, and the communication and contemplation between.”4 That communication and contemplation, “the meaning of a thing,” were all-important: “A purely cold abstraction doesn’t interest me too much … Art has to have some kind of humanly touching and memorable quality. It has to recall something which moves a person—a recollection, a recognition of his loneliness, or tragedy, or whatever is at the root of his recollection.”5

* * *

The infusion of humanity into Noguchi’s sculptures was subtle and tender. It had none of the brash energy of the work of other sculptors associated with the New York School. Many of his sculptures were anthropomorphic, but in terms of feeling they were more contemplative than aggressive. Noguchi was not an Expressionist. He preferred calm and stillness, meanings that were timeless rather than immediate or passionately personal. His work’s slow tempo alludes to emergence and growth. It is movement felt at the core of matter: “We see the exterior of the tree and inwardly we see the sap rising. The forms I try to create are not merely the appearance but the resonating energy inside … It is not movement going anywhere, but motion of a different sort. Inside matter there are atoms constantly in motion: if we could hear this action, we could probably hear a continuous sound. There is a roar created by mutual communication inside matter. What I wanted was that resonating energy inside.”6

When Noguchi designed the interlocking sculptures, he first worked out the basic shapes in pencil on graph paper and then laminated the sheet of drawings onto black cardboard or craft paper. Next he cut out the contours of the drawn shapes with a razor blade without cutting into the black cardboard or craft paper. After peeling away the graph paper shape, he would examine the resulting silhouetted black shape. If a shape satisfied Noguchi he would then take the graph paper shape he had just peeled, paste it onto another sheet of black board, and cut the shape out of the board. The cut-out shapes could then be assembled to create miniature three-dimensional models for future slab sculptures by cutting slots or notches and then fitting the sections together. He would place these models on a miniature stage where he could move them around to see how his sculpture would look from all sides.

When it came time to translate his drawings into stone sculptures, the graph paper drawings helped Noguchi size up his shapes onto a large sheet of paper. He would cut the enlarged shape out of the paper to create a template whose contours he would trace onto a flat sheet of stone—usually marble—laid on sawhorses in his courtyard. Next he would cut the shape out of the stone using a circular saw with an eight-inch blade connected by a flexible shaft to a portable generator.7 After a section of a sculpture was cut, he would cut out the peripheral notches that would make it possible to fit his interlocking shapes together.

The vitality of the voids between shapes gives Noguchi’s interlocking slab sculptures a light and delicate poise. Some sculptures are noble and eloquent. The rather Picassoid Figure, the first slab sculpture he carved out of a marble in 1944, and Kouros have a definite hauteur. Others in the series, like Fishface, Strange Bird, To the Sunflower, and the priapic Man, are funny. Humpty Dumpty, a vaguely ovoid three-legged creature with a hole for an eye and various sproutlike shapes protruding from an opening in his chest, is both droll and sad. Indeed, its arch shape predicts the rather menacing anthropomorphic arch of his 1952 model for a memorial for the victims of the Hiroshima bombing. Noguchi told Katharine Kuh that Humpty Dumpty had to do with “things that happen at night, somber things … There are many sides of me I want to express—the loneliness, the sadness, and then something about me which you might call precise and dry which I want to express as well. I wouldn’t want to express only my serious side—I’m also playful sometimes—and then again completely introspective.”8

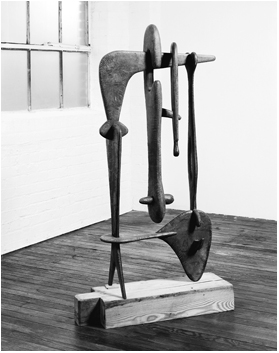

Remembrance, carved out of mahogany in 1944, brings to mind the mood of loss and longing in Gorky’s 1933 drawing series titled Nighttime, Enigma, and Nostalgia. The vertical elements on the left and right suggest two figures—a man and a woman, separated by a void. In this case, the boomerang shape—that favorite shape of Surrealist-inspired artists of the mid-1940s—could be the man’s head and the palettelike shape that forms one of the sculpture’s supports could be the female. The elements hooked over the boomerang seem to express helplessness and grief.

Man, 1945. Wood, 525⁄8 × 19¾ × 125⁄8 in. Private collection, New York

Humpty Dumpty, 1946. Ribbon slate, 59 × 20¾ × 17½ in. (Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York)

Remembrance, 1944. Mahogany, 50½ × 245⁄8 × 9 in.

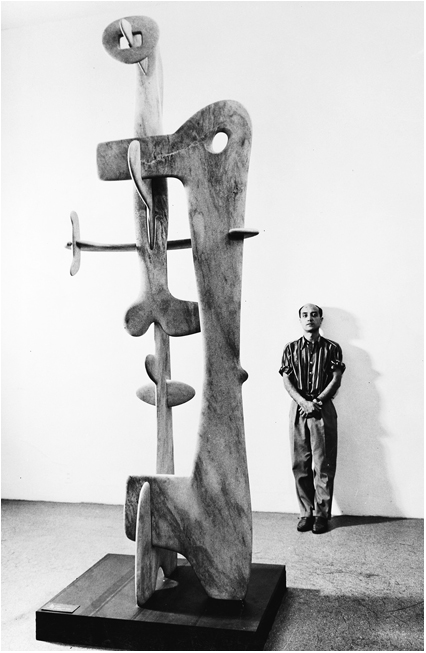

At nine feet, nine inches tall, Kouros, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is the largest of the interlocking slab sculptures. In a November 1945 letter to Ann, Noguchi said that the sculpture expressed “an affirmation … I wanted something purposeful[,] bigger than our individual selves, classical and idealistic—representative of something that doesn’t pass with the passage of time.” Kouros was inspired by the formal simplicity of archaic Greek Apollonian figures. Indeed, Noguchi had a photograph of a kouros in the Louvre pinned to his studio wall.9 The luminous pink marble from which Noguchi’s Kouros is carved suggests youthful flesh. The figure’s frontal stance, like that of an archaic kouros, has perfect equipoise. As in the Egyptian standing figures from which the Archaic Greek kouroses were derived, Noguchi’s “effigy of man” is conceived with some of its forms facing forward and some facing sideways and at right angles to the frontal forms. Like Man from the previous year, Kouros has a small roundish head with a hole cut out of it through which projects what must be a nose. Like Man also, it has a protruding phallus, but here the sexual imagery is more subtle and, as in his friend Gorky’s paintings, Noguchi’s shapes are multivalent. With its perfect balance between solid and void, between verticals and horizontals, and between figuration and abstraction, Kouros manages to be at once powerful and poetic, majestic and tender. Noguchi observed that “the structure of Kouros defies gravity, defies time in a sense. The very fragility gives a thrill; the danger excites. It’s like life—you can lose it at any moment…”10

Since his Associated Press plaque of 1938–39, Noguchi had received very little public attention, but the interlocking sculptures of the mid-1940s brought him back into view. Museums took an interest. Late in 1945 Kouros stood near the entrance desk at the Museum of Modern Art. In the spring of 1946 he contributed Figure, his earliest slab piece, to the Whitney’s Sculpture, Watercolor, and Drawing annual exhibition. In the March issue of Art News, Thomas Hess wrote of the show: “First of all, and almost dominating the entire museum, is Noguchi’s FIGURE. This monumental work is made of pink-blue Tennessee marble and has a splendid powdery-smooth surface. The grooved forms slide into each other like finely machined parts.”11 Fourteen Americans, one of a series of American shows that curator Dorothy Miller organized for MoMA over the years, opened on September 10, 1946, and included three sculptors—Noguchi, Theodore Roszak, and David Hare. Among the painters were Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell, Irene Rice Pereira, and Mark Tobey. Noguchi’s work garnered a great deal of praise. He submitted Lunar Infant, the model for Contoured Playground, My Pacific, Monument to Heroes, and Katchina, all from the first half of the 1940s. Of his more recent work he contributed Time Lock and Kouros, as well as two interlocking slab sculptures from 1946, the black slate Gregory and the white marble Metamorphosis.

Noguchi with Kouros (ht. 117 in.) at the Fourteen Americans exhibition, 1946, Museum of Modern Art, New York (Eliot Elisofon / The LIFE Picture Collection / Getty Images)

Noguchi’s statement printed in the exhibition’s catalogue was his current sculptural credo:

The essence of sculpture is for me the perception of space, the continuum of our existence … Since our experiences of space are, however, limited to momentary segments of time, growth must be the core of existence … growth can only be new, for awareness is the everchanging adjustment of the human psyche to chaos. If I say that growth is the constant transfusion of human meaning into the encroaching void, then how great is our need today when our knowledge of the universe has filled space with energy, driving us toward a greater chaos and new equilibriums.

I say it is the sculptor who orders and animates space, gives it meaning.”12

Over the years, Noguchi would place greater and greater emphasis on giving form to space. He also stressed growth and change, important not only for his art’s formal development but also for the way his sculptures seem to be in the process of emerging and metamorphosing. His words about the adjustment of the human psyche to chaos and the void resound with that existential angst that was so pervasive (and fashionable) in the postwar years.

Thomas Hess’s 1945 Art News article on Noguchi proclaimed (in that highfalutin tone typical of the late 1940s and 1950s and with a nod to James Joyce): “In the smithing of his soul he has forged the uncreated conscience of his race—humanity.”13 But, Hess noted, since 1938, Noguchi had been in a kind of exile, and that he “carried his exile inside him like a skeleton.” What Noguchi had done was to fuse “in his art the East and West as they were fused in his body.”14 He concluded his essay with the prophesy that if Noguchi felt his art was turning into a formula he would “with the great courage which has characterized his whole career, return to exile, and with his tools of silence and cunning create sculpture in the dual reference of art and life.”15

Noguchi’s room of sculptures at the Museum of Modern Art delighted most reviewers, but New York’s most powerful critic, Clement Greenberg, characterized Noguchi’s sculptures as having “excessive taste, excessive polish, smoothness of surface, excessive clarity, and precision of drawing.”16 A review in Art Digest declared that Noguchi had reached “the intangible and superreality through the abstract,” yet described the work as “a little cold.”17 Similarly, later critics would be put off by a coolness detected in Noguchi’s work. Although his sculptures are certainly reticent, sometimes to the point of standoffishness, their coolness has, I think, to do with their contemplative quality. He was not communicating the tumult of his unconscious.

In November Life magazine published a three-page article on Noguchi that is smugly philistine. “At least a dozen top U.S. critics and museum heads believe that the puzzling objects shown at left and right … are first-rate art.”18 Noguchi, the author said, “patters happily about in his bare feet, cutting up marble slabs to fashion even more statues like those on the preceding pages.” For all the condescension, the attention in such a mass-circulation magazine certainly increased Noguchi’s fame.