During the period of his attachment to Tara, Noguchi worked on sets for Martha Graham’s Night Journey (1947), which was based on the theme of Oedipus and his mother, Jocasta, who, when she discovered that she had had intercourse with her son, committed suicide. For this dance, Graham asked Noguchi to produce a bed, and he made one whose tilted surface, shaped into bonelike forms that stood for a recumbent male and female, was, for the dancers, wildly uncomfortable. “Martha wanted a bed. I made a nonbed.”1 Another set that Noguchi designed for Graham in 1947 was the Miróesque Errand into the Maze, in which he used white rope to depict Ariadne’s path into the Minotaur’s labyrinth—what he called the “inner recesses of the mind.”

Also in 1947 Noguchi designed the set and costumes for Merce Cunningham’s The Seasons. Cunningham, who had once been a member of Martha Graham’s company, had, along with the avant-garde composer John Cage, been commissioned by Lincoln Kirstein to do a piece for the recently founded Ballet Society. Immersed like Cage in Oriental philosophy, Cunningham wanted the dance to be cyclical, so he took the theme of the seasons. Noguchi described the dance as “a celebration of the passage of time.”2 Although he sometimes called time a “monster,” his Japanese childhood gave him a special sensitivity to time’s cycle. Noguchi designed a very simple set—a few mounds articulated with stripes to create a landscape, plus, at one moment, a spare web of rope spanning the proscenium, and at another a structure made of rods. He also designed striped costumes and masks that Cunningham said were beautiful but difficult to use because “you had to hold them in your mouth in the Japanese way. If you opened your mouth to breathe the mask fell out.”3 The striped costumes were, Noguchi said, “comic and sad—like the human condition.”4 Cunningham recalled that the female dancers were unhappy with their tufted leotards: the stripes were stuffed so that they puffed out and the dancers felt this made them look fat. Tanaquil Le Clercq, who danced a pas de deux with Cunningham for “Summer,” recalled that “for spring the girls tied on little tails. This always got a terrific laugh, which made Merce angry.”5

Cunningham and Noguchi’s collaboration was not always easy. Cunningham frequently had to adjust his dance to Noguchi’s ideas, while Noguchi felt that some of his props were misinterpreted and used for the wrong seasons. But both men respected each other enough to resolve their differences. After only one full rehearsal of The Seasons, there was a crisis when suddenly they had to change theaters and perform at the Ziegfeld. Noguchi had planned to project film of actual snow and rain on a backdrop, but the Ziegfeld had no camera equipment. “I had to dash out for some stock snow and project it with a lantern slide.”6 As Cunningham observed, “Noguchi knew how to find ways to bring what he wanted about.”7

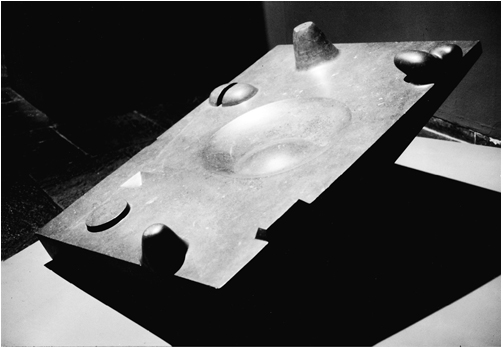

One of the theater projects that meant the most to Noguchi in 1947 and early 1948 was his collaboration with George Balanchine and Igor Stravinsky on the ballet Orpheus. He designed the costumes, props, and set, which consisted of mounds shaped like the cones of sand in Zen gardens, pale roundish rocks that levitated, and a few flat bell shapes. The Orpheus myth had great appeal to Noguchi: “Never was I more personally involved in creation than with this piece which is the story of the artist. I interpreted Orpheus as the story of the artist blinded by his vision (the mask). Even inanimate objects move at his touch—as do the rocks, at the pluck of his lyre. To find his bride or to seek his dream or to fulfill his mission, he is drawn by the spirit of darkness to the netherworld. He descends in gloom as glowing rocks, like astral bodies, levitate…”8 Likewise, a few years later Noguchi would see the rocks in his Chase Manhattan Bank water garden as seeming to levitate.

While Cronos, The Gunas, and Avatar (all 1947) continued the interlocking slab sculpture mode, that same year he also produced a number of openwork wall pieces such as Bird’s Nest and Rice Fields with Insects, made of wooden dowels that go every which way. Precedents for this new kind of sculpture can be seen in Medea’s fragile wire dress in Cave of the Heart and the structure made of wooden rods that served as a prop in The Seasons. He also made sculptures that he called landscape tables. Night Land harks back to Giacometti’s No More Play (1931–32), a square of marble with round holes scooped out of its surface that resembles a game board. Night Land’s luminous dark marble surface, with its circular hollow and mound and its emergent shapes suggesting gestation, brings to mind the barren dream landscapes of Surrealism. Tilted and seeming to float just above the floor, the sculpture pulls the viewer into a dark landscape of the mind.

Bird’s Nest, 1947. Wood dowels and plastic, 16¾ × 18 × 13 in.

Night Land, 1947. York fossil marble, 22 × 47 × 37½ in. (Courtesy of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City; gift of the Hall Family Foundation)

In 1947 Noguchi did some design work as well. He made a sculptured ceiling for the Time and Life building’s reception room, as well as a ceiling for the American Stove Company in St. Louis. Both had biomorphic, recessed shapes lit, like his Lunars, from within. “At some point,” Noguchi said, “architecture becomes sculpture, and sculpture becomes architecture; at some point they meet.”9 He hoped that the integration of sculpture and architecture would create functional environments that made people happy. In the summer of 1948, for the stairwell on the promenade deck of the SS Argentina, Noguchi created Lunar Voyage, a wall of molded magnesite with electric lights inserted into its crevices. “My idea was to create a completely artificial environment inside, the interstices from which light would emanate, so that one would, in a sense, be inside a sculpture.” It was an impulse that he would return to in his later work.

In March 1947 Noguchi took part in an exhibition called Bloodflames, organized by the Surrealist critic and poet Nicolas Calas for the Hugo Gallery at 26 East Fifty-seventh Street. Exhibitors included Gorky, Wilfredo Lam, Matta, Hare, Helen Phillips, Gerome Kamrowski, and Jeanne Reynal. The architect Frederick Kiesler created an appropriately surreal setting and provided “boomerang frames” to support the paintings. Calas’s catalogue essays on the various artists were abstruse but insightful. The section on Noguchi said his work was so “dictated by the desires of the unconscious” that it evoked fecundity, “sex and fear,” and that Noguchi was “a jeweler turned magician … sometimes the earth itself, with its erosions and fissures, is transformed into a pillow for our dreams.”10

That March a reporter for the Nippon Times came to interview Noguchi at his MacDougal Alley studio. Legend has it that Noguchi learned from this reporter that his father was still alive. In fact Noguchi had been in touch with his father’s family as early as March 1946. Four decades later Noguchi recalled the reporter’s visit: “I said the war was because the Japanese people did not have a voice and that they did not have individual rights…”11 He also told the Nippon Times that the creative efforts of individuals and the fostering of handicraft would be Japan’s salvation.

On May 6, 1947, Yone wrote to Noguchi that he had been at the United Press Office in Tokyo and a Mr. Hobright had shown him the article:

I know you are doing a very distinguished work of which I feel so applaud. Oh if your mother is living today and sees you of today!… I lost almost everything from books and moments [sic] to things of daily necessity … But I say this not for your sympathy. War is terrible particularly when we lost it. Inflation, inflation—we do not know how it goes up. Though we have no decent clothes to wear, we can not buy them because we have to pay an impossibly fabulous prise [sic] for them … if you come to Japan again you will see her certainly in a different aspact [sic]. I am getting old and feel sad and awful with what happened in Japan. But I have no complaining about it.12

Noguchi took his father’s despair to mean that Yone regretted his former support for military aggression. On May 15 Noguchi wrote his father back, saying, about the Nippon Times piece, “I hope you agree that individual creativity should be fostered in these totalitarian times … I should so much like to help in bringing back the dignity of individual labor in the Orient.”13 Once he had located his family, he sent them care packages. In late June, the bed-ridden Yone, who was dying of cancer but did not know it, wrote to Noguchi that his letter had made him weep with joy: “I could not speak for some moment … Your [sic] very kind to send me a living necessaries which I need very badly. I can not say what I want because whatever you sent me is all welcome.”14 A few weeks after Yone’s June letter, Noguchi’s seventy-two-year-old father died.

* * *

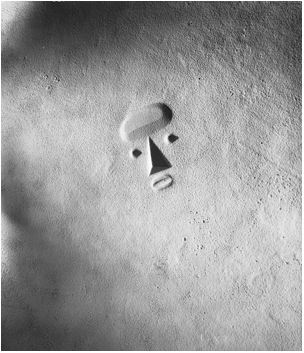

Thoughts of transience and mortality, perhaps prompted by his father’s death, are emblematic in Noguchi’s 1947 design for a sculpture that may have been intended as a memorial for his father as well as a memorial for mankind. Sculpture to Be Seen from Mars was to have been a ten-mile-long earthwork in the shape of a highly schematic, yet poignant, human face—the face of everyman looking up at the universe. Noguchi’s idea was that it should be built “in some desert, some unwanted area.”15 The pyramid that stood for the nose was to have been a mile high. The model was, Noguchi said, “a flight of the imagination. Made of sand on a board about one foot square and photographed.”16 Noguchi thought of the immense face as someday becoming a vestige of an extinct civilization, proof to inhabitants of Mars that humanity had once lived on earth. Horrified by the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he often spoke of his fear of atomic annihilation. Whether it honors his father or the extinction of human life or both, and even though it is recalled only in a photograph of a model formed out of sand, Sculpture to Be Seen from Mars stuns the heart with its pathos.

Sculpture to Be Seen from Mars, 1947. Model in sand, 1 in. square. Destroyed