Leonie booked steerage-class passage on the Mongolia, a Pacific Mail Steamship Company vessel, and on March 9, 1907, she and Isamu left Los Angeles bound for Japan via San Francisco. There were 1,400 third-class passengers, mostly Chinese laborers, crammed into the lower decks. Leonie and Isamu had a small cabin under the boiler room.1 For most of the seventeen-day trip, Isamu lay seasick in his baby carriage. When the ship docked at Yokohama, not far from Tokyo, on March 26, Yone was there to meet them. “The arrival of my two-year-old boy, Isamu, from America was anticipated as it is said here, with crane-neck-long longing. This Mr. Courageous [the Japanese ideograph for Isamu means “brave”] landed in Yokohama on a certain Sunday afternoon of early March…”2 Hitherto called Baby, Bob, or Yo, Noguchi was finally given the name Isamu.

Yone boarded the ship and found his way to Leonie and the baby’s cabin. In his autobiography, published in London in 1914, he described the calm, yellow sunlight that lit the carriage in which lay the “little handful of a body” of his half-asleep son. “Now and then he opened a pair of large brown eyes. ‘See papa’; Léonie tried to make Isamu’s face turn to me; however, he shut his eyes immediately without looking at me, as if he were born with no thought of a father … I thought, however, that I could not blame him after all for his indifference to father, as I did not feel, I confess, any fatherly feeling till, half an hour ago.”3

As Yone and Leonie pushed Isamu’s carriage toward the train and then home, Yone realized how everything must seem strange to Isamu, the street sounds, the language, the way people looked, and the melancholy clacking of wooden geta on the pavement. Leonie was cold and exhausted. Isamu was pale and thin, and Yone wondered what had happened to the plump baby that Leonie had described. Isamu was quiet but not peaceful: “Now and then he opened his big eyes, and silently questioned the nature of the crowd which, though it was dark, gathered round us here and there.” A white woman pushing a baby carriage containing a not-quite Japanese-looking child was a curious sight. “In no more than the dying voice of an autumn insect, Baby suddenly asked mother where was his home.”

For the next several days Isamu kept crying. “It tried my patience very much,” Yone recalled, “and I did not know really what to do with him. He cried on seeing the new faces of the Japanese servant girls, and cried more when he was spoken to by them.” He kept on crying when Yone gave him a present of a Japanese toy dog made of cotton. “My earliest memories are not happy,” Noguchi wrote years later, “nor do I think back on my later childhood as being particularly so in spite of Japan being a child’s paradise.”4

On his fifth day in Tokyo, Isamu told his mother that he wanted to go home to his grandmother in Pasadena. “Where’s Nanna?” he asked. “Far, far,” said Leonie. Isamu repeated her words several times and then turned white and silent. To cheer him up Leonie said, “Baby, go and see papa.” Isamu moved toward Yone’s room and slid the shoji open a crack, but when his father turned to look at him he shut it quickly and ran to Leonie crying, “No, no!” Yone heard Isamu tell Leonie that his father was not there. “I must have appeared to his eye as some curiosity, to look at once in a while, but never to come close to. However, I was not hopeless; and I thought that I must win him over, and then he would look at me as he did his mother.”

No matter how hard Leonie tried to create a bond between Isamu and Yone, Isamu was his mother’s child. His father remained a distant figure, probably more so as the months went on and Yone’s double life became more embroiled. His common-law wife Matsuko became pregnant the month that Leonie and Isamu arrived. The demands of two households must have been anathema to a man as self-absorbed as Yone, a man who longed for solitude and to “live in poetry.”

In the beginning Yone did try to fulfill his promise to Leonie to be a good father. He was amused that when he clapped his hands for the servants, Isamu would come running and kneel before him just like the housemaids. “I was much pleased to see that he was growing familiar with me. And he even attempted to call me ‘Danna-Sama’ (Mr. Lord), catching the word which the servants respectfully addressed to me. It was too much, I thought; however, I could not help smiling delightedly at it.” Leonie and Yone may have exacerbated Isamu’s cultural confusion. “You Japanese baby?” Leonie asked, and Isamu turned to his father and said yes. When Yone asked him if he would like to remain an American, he turned to his mother and said yes.

Soon after arriving in Tokyo, Leonie wrote to Putnam about what it was like joining the “husband” whom she had not seen in almost three years. “Yone and I don’t fight, but as far as happiness with a capital H, why I fear we are both too selfish as you say. Yone changed so much I would hardly have known him—especially in the shape of his nose and the acquisition of a moustache. Yone seems to like the Boy tho’ he doesn’t approve of his manners which have suddenly flowered into a sort of wild Indian Savagery amazing and dismaying. (For much attention has turned his little head.) Everybody calls him ‘Bo-chan’ which is Baby-Lord, and I tell you he lords it over them.” She was lonely, she said, especially because she did not speak Japanese, and her usual independence was thwarted by the difficulty of finding her way around Tokyo’s tangled unpaved streets.”5

Noguchi’s memories of his childhood were vague: “It’s difficult to piece together what was my childhood,” he told an interviewer in 1988.6 “My clearest recollection is of riding on somebody’s back and being fondled and enjoying myself immensely. There was a bamboo fence, I remember, and I would peer across it, and this was, you might say, my one clear recollection, of, you might say, happiness—of having finally found a situation of security. I think my feeling towards Japan comes from this very initial sort of relief that I felt of being safe and on ‘terra firma,’ coming across the ocean on a shaky boat must have been unpleasant for me.” Yet he recalled that insecurity was “a fixed part” of his childhood. The open space of a playground on a hill near his father’s house, for example, filled him with foreboding. When cherry blossoms fell and scattered soon after he arrived in Tokyo he was saddened.7 “Things which are so far back are not like a part of myself, more like the life of somebody else,” he wrote in his autobiography. “To me it all seemed like chance. Choice, if any, came much later.”8

As the weeks went by the scrawny toddler that Yone had welcomed in Yokohama turned into a plump, healthy boy. He came to love Japanese food. After eating breakfast with his parents he would go into the kitchen and share a second breakfast of rice with the servants. He also liked wheat gluten candy made in the shapes of animals. Every morning the candy salesman would walk along the street beating a drum to advertise his wares. “Donko, don, donko, don, don,” Isamu would cry in imitation of the drumbeat. He would then insist that one of the servant girls carry him on her back with his bottom perched on her obi (a wide sash worn with a kimono), as is customary for Japanese children.

Isamu quickly picked up Japanese words and customs: when a guest departed he would call “Sayonara,” and when an uncle gave him an American and a Japanese flag he shouted “Banzai!” Soon he ventured out beyond the garden to play blindman’s buff with the neighborhood children who at first had looked at him as an oddity. When children passed the house they would shout “Baby san,” thinking that was Isamu’s name.

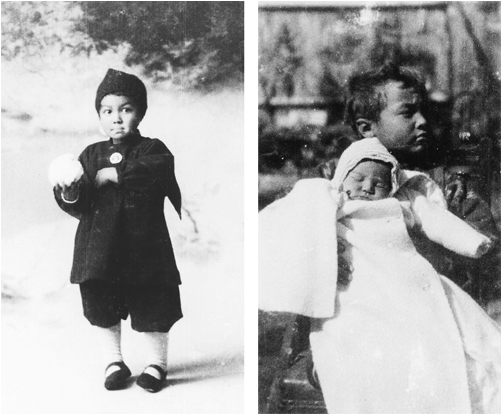

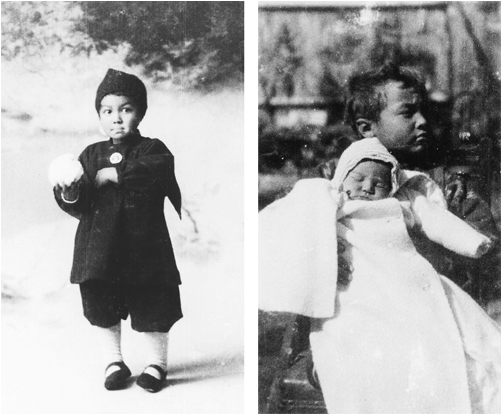

Isamu in Tokyo, aged about five (left); holding his half-sister, Ailes, 1912 (right)

Isamu played with any household object that he could move. He kept on sliding the shoji open and shut and Yone had to hide the clocks because Isamu would wind them so tight that they no longer functioned. In the evenings as he sat with his parents, he enjoyed chasing their shadows. When his own shadow vanished behind another shadow he looked downcast. “Go to papa!” Leonie would then say. “He will give it to you.” Isamu would poke and prod his father’s kimono in search of his shadow until Yone would say, “There it is, Baby,” and would move aside to let his son’s shadow reappear on the wall.9

Although Isamu often tried his father’s patience, Yone indulged him. Whenever Yone passed a store he would look to see if there was something that he could buy for Isamu. If Isamu delayed his bedtime by insisting on seeing the moon, Yone would hang a lamp with a blue globe on the other side of a shoji screen and Isamu would soon be contentedly asleep. “Any child,” Yone noted, “appears wonderful to his father; so is Isamu to me. I confess that I made many new discoveries of life and beauty since the day of his arrival in Japan.”10

By the time these memories of Isamu’s early Tokyo days were published, Isamu was ten and had been living apart from his father for many years. Yone’s visits were rare. Noguchi told an interviewer, “Our family really had no cohesion. I should hardly say ‘our family’ because I did not belong to his family.”11 Not only did Yone have another family he was attending, but also he took weekly sojourns in Kamakura, a seaside town about an hour southeast of Tokyo that was once Japan’s capital city and is famous for its many Buddhist temples. Yone would repair to one of the largest, Engaku-ji, a beautiful Zen Buddhist monastery founded in the thirteenth century that is spread over a vast area and comprises many subsidiary temples. Yone’s routine was to teach at Keio University two days a week and then spend the rest of the time in Kamakura, away from the mundane demands of his two families. In 1910 he published a compilation of his poetry and essays called Kamakura, in which he wrote about his pleasure in the monastery’s gift of solitude and in the calming Buddhist rituals.12 On May 19, 1907, less than two months after Leonie and Isamu’s arrival in Tokyo, Yone wrote to Charles Stoddard from his temple retreat: “Yesterday, my boy Isamu and Mrs. Noguchi were here, making some noise; and last night, they returned home in Tokyo, leaving me in my beloved Silence without which I cannot exist.”13

With Yone’s help, Leonie found pupils who wanted to learn English. In July 1907 she wrote to Catherine Bunnel thanking her for sending a sponge cake recipe and telling her a little about her students—a lieutenant, a professor of electrical engineering, and a banker. Leonie also planned, starting in September, to teach two mornings a week in a small girls’ school run by a Mrs. Sakurai. About Isamu, she reported that he was picking up Japanese quickly but that she herself was not.14

The winter of 1907–08 was difficult for Leonie. When Yone and Matsuko’s daughter Hifumi was born that December, Yone registered her birth. But he never registered Isamu, and when he had a son in 1909 he listed him in the household register as his firstborn son. Presumably Leonie was ignorant of these births, but Yone was less and less attentive to her and to Isamu. On February 26, 1908, Leonie wrote to Putnam: “I felt generally miserable in my innards this winter—too cold.”15 Japanese houses had no central heating—a brazier was the only source of heat, and the paper shoji panels did little to keep out the cold. “I’m homesick for the country—Japanese country, American country, any country where there are fields and blossoms and breezes and unscented by city odors. And a garden. I’m just crazy to dig. But we are shut up in Tokyo, and likely to remain so for the rest of our natural lives, unless we happily die young … And poor Baby! ‘What are you doing baby?’ I called out, seeing him holding his wooden geta, with trowel in hand. ‘Nothing, mama, nothing,’ he answers. ‘Nothing to dig.’”

On March 13, 1908, Leonie wrote to Catherine: “I have had only one week’s vacation from teaching since I came here. That was last summer. And in spite of my best endeavors I can earn only some 85 yen a month, with which it is not easy to keep house, keep a girl to take Isamu to school, keep us all in clothes and shoes, and send 20 to mama every month. It takes as hard work to earn that 85 yen as to earn as many dollars in America, but it doesn’t go nearly as far since most of the staples, bread, butter, sugar, chocolate, oatmeal etc are imported from America.” Yone contributed part of his salary to help with household expenses, but in general, Leonie said, she was “footing it alone here. Yone in his temple in Kamakura is happily oblivious of the cares and worries of this sordid world. There he spends his time sleeping, smoking, writing divine poetry, emerging twice a week to lecture at Keio College.”16

In spring 1908 Leonie and Isamu moved to 90 Myogadani Street in the Koishikawa district, “a tiny little house on a hilltop close by a grove of tall trees where a Ho Ho! Kikyo! (nightingale) sings to me daily.”17 She also reported to Catherine that Yone was back in Kamakura. “He has engaged a room in a temple where he can write in peace, far from the madding crows of Baby and me. Incidentally this leaves me in something like your idea of earthly bliss—a little house, one pretty little maid servant, and nobody to bother. Isamu thrown in for good measure. I’m quite enjoying it. Chance to get some work done. That means typing Yone’s new book chiefly, with teaching, housework etc—thrown in. Really awfully busy.”

In July Leonie and Isamu spent two weeks at the seashore at Yaidzu in Shizuoka, where they were invited by Leonie’s friend Setsu Koizumi, the widow of Lafcadio Hearn, an American Japanophile writer who had taught English literature at Tokyo Imperial University. Hearn and Koizumi’s two older sons had been Leonie’s pupils since the previous autumn. Their two younger children were eight and five, young enough to be Isamu’s playmates. Yone, who had just finished writing a book about Hearn, was impressed that Leonie was staying in a house where Hearn had spent his summers.18 Noguchi remembered: “My mother used to take me along with her to call on people. Among them was the family of Lafcadio Hearn, whose children she taught for a while. The Hearn family lived in Okubo and had a beautiful garden. Thus cautiously did I come to know the world.”19

On June 13, 1909, Leonie wrote to Catherine about how independent and full of curiosity four-and-a-half-year-old Isamu was. “He is everything to me,” she said.20 She noted her son’s attraction to mechanical things and to nature, two interests that would persist in his adult life and that would greatly affect his art. Testifying to his interest in nature and in working the earth, a neighbor reported, “One day Isamu-san covered the whole front gate of the house with gobs of mud. I didn’t actually see him do that but I did see the gate completely covered with mud when I passed by. His mother did not scold him at all. Without fussing she simply had the maid clean the gate off with water.”21

The following April Leonie took a part-time job teaching English at the Kanagawa Prefecture Girls’ Higher School in Yokohama.22 She wrote to Catherine on November 3, 1910, that at his school Isamu had made a sketch of the sea that he called “Ibariken by Moonlight.” It was so subtle that “you had to look hard to see anything on the paper—and then you perceived some faint blue lines representing the waves of the sea, with a few pale yellow sails on it.”23 He had, she said, decided to become an artist instead of a soldier. “‘Why?’ said I. ‘Because’ said he ‘all the soldiers got to die, and I don’t want to die. Even a general has to die.’” She told Catherine that because the commute to her teaching job was too long, she was thinking of moving once again and had found for Isamu a private kindergarten that had just been opened by a man named Morimura. It had “Goats, chickens, monkey, peacock, sea-saws, swings etc. Very small, very high-toned, a trifle expensive … Isamu says he likes it ‘because it is such a beauty garden.’”

When she next wrote Catherine on December 23 Leonie and Isamu had moved to a small house surrounded by fields in Omori on the southern edge of Tokyo. Omori was on the water, but their hilltop house looked inland toward Mount Fuji. Of her life with six-year-old Isamu, she reported that they had been to the Russian Circus: “Isamu was in ecstasies. There was one man Mr. B—famous horse trainer. Isamu whispered to me: ‘He is a Great Man!’ Poor little Isamu. His hero worship is strangely placed. He told his papa the other day that he hoped to become a great man some day, but that he could not become so great as mama. Tonight he is busy making a book. His cheeks are red red roses. I think the country air does him good.”24

Isamu’s year at the Morimura School was happy. Compared to most Japanese schools it was progressive. It valued individualism and the students did not wear uniforms. A photograph taken in 1911 of Isamu’s graduating class shows six boys and four girls. Behind them stand the staff of nine women and one man, who may be Mr. Morimura. Isamu is the smallest boy and the only child who holds his rolled-up diploma to his mouth as if it were a flute. On the first page of his autobiography Noguchi wrote: “My first recollection of joy was going to a newly opened experimental kindergarten where there was a zoo, and where children were taught to do things with their hands. My first sculpture was made there in the form of a wave, in clay and with a blue glaze.”25 His wave sculpture was, he recalled, “much talked about in kindergarten and my mother never forgot it. She kept hoping I would eventually become an artist.”26 Looking back near the end of his life, Noguchi remembered his attendance at the Morimura School as pivotal: “My awakening to consciousness out of this dark and uncertain time came with my being taken to Morimura Gakuen … I was finally among people who seemed to take me as one of them, or rather, as somebody of interest to them, somebody that they related to as a student, appropriate, I imagine, to my being there … and a half-breed person such as myself was a welcome addition, I believe.”27 The feeling of being accepted, of not being treated as a gaijin, was to Isamu a great relief. Even if at that young age he would not have known the meaning of prejudice, he surely felt it. He came to realize that “the Japanese do not accept foreigners as another person equal to themselves”28 and he continued to be touchy about his mixed blood, his being foreign, and his illegitimate birth for the rest of his life.

On May 3, 1911, Leonie wrote Catherine that in Omori she knew only one of her neighbors, but that Isamu had friends. She described Noguchi’s cleverness in circumventing discipline. When she told him it was time for bed, he countered, “I can’t go now, because I told the neighbor’s boy I would not go to bed so early, and I have to tell the truth.”29 Perhaps that neighbor’s boy was the teenage Tomio Iwata, who did in fact live next door and who recalled that Isamu, for all his resistance to bedtime, “never behaved like a spoiled child or acted petulantly toward his mother. Rather, he treated his mother like a teacher—with respect.”30 Iwata delighted in teasing Isamu: “Isamu was always too proud to admit defeat or give in, and he was greedy about food, so he was an easy target to teasing and torment.” Once Tomio hoisted Isamu up onto an exercise bar and left him dangling with his feet too far from the ground for him to jump. “Isamu began to scream his lungs out … I just pretended I didn’t hear or care. Then suddenly the gate swung open, and Mrs. Leonie came bounding into the yard as fast as a rabbit. Without a word she grabbed Isamu, hugged him to her body, and immediately fled back to her house.” Noguchi said that he and his mother were “very close and in fact I had nobody excepting for her. She was, you know, my total link to life, and I’m sure that this was not good for me, but that was the case.”31