Upon his return to New York in September 1950, Noguchi moved into the Great Northern Hotel at 118 West Fifty-seventh Street. Having been away for a year and four months, he felt like a stranger. “New York was totally unreal. I lived only with thoughts of how to get back again to Japan. The book for the Bollingen Foundation was a box of notes and photographs. I felt inadequate to bring order into the manuscript. How can one write with wisdom unless ones [sic] own problems are solved?”1

He applied for an extension of his fellowship and “rather forlornly” began visiting galleries to see what he had missed.2 He discovered that in the last two years, his friends in the New York School had moved from Surrealist-inspired semiabstraction to abstraction in which the mythic imagery was banished, but continued to pervade the paintings’ atmosphere as an aura of primal feeling. Even though he always prided himself on not being part of any group, Noguchi felt left out. His contemporaries were having gallery exhibitions and gaining critical renown. He must have had a twinge of envy when he learned that Jackson Pollock, de Kooning, and Gorky had represented the United States at the 1950 Venice Biennale. “I was the absent one.”3 Noguchi told Paul Cummings that whenever he returned to New York from Japan he felt “at a loss” and “a little bit removed. I don’t like it … I have to be in contact … in Japan the contact is not with people but with the earth.”4

Noguchi saw that the sculptors of his generation, people like David Smith, Seymour Lipton, and David Hare, were all creating sculptures in welded metal. Their work expressed passions that were urgent and sometimes agonistic. By contrast, Noguchi wanted to create sculptures that were about being part of the natural world. He told Katharine Kuh: “I don’t think it is so necessary to be concerned with oneself. If you are continually polishing up your signature, it ends by being about all you do … In a sense I feel the more one loses oneself, the more one is oneself.”5

In spite of feeling out of step with his colleagues, Noguchi did receive a fair amount of attention in the early 1950s. In January 1951 the Museum of Modern Art opened a show called Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America curated by Andrew Carnduff Ritchie, which included works from the early part of the twentieth century up to the present. The contemporary artists were the Abstract Expressionist painters Pollock, de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Motherwell, and Kline. Among sculptors, besides Noguchi, were Lipton, Ibram Lassaw, Herbert Ferber, Calder, Smith, Richard Lippold, Theodore Roszak, José de Rivera, and Peter Grippe. Everyone except Noguchi worked mainly in metal. In November 1950 his article “Notes by an Artist on His Recent Work in Japan” was published in Arts and Architecture. Five months later Interiors magazine ran a piece on Noguchi’s exhibition and projects in Japan.6 In 1952 Harper’s Bazaar published Noguchi’s article on Kabuki theater.7 And even better than the press recognition, Noguchi was approached by Antonin Raymond to do a garden for Reader’s Digest’s new headquarters in Tokyo.

Antonin Raymond was the designer of the Sri Aurobindo ashram in Pondicherry, India, which Noguchi had visited during his Bollingen travels. No doubt he and Noguchi had met at the time of Noguchi’s Mitsukoshi show. On October 25, 1950, Raymond wrote saying that he needed Noguchi’s help. He told Noguchi that in his New York office there was a site plan and a survey that Noguchi could use to make a model for the garden. “I so need somebody to help me think and design,” Raymond wrote. “I have to make decisions altogether too quickly, without feeling it out…”8

On November 22 Raymond wrote to Lila Acheson Wallace, Reader’s Digest’s cofounder, telling her that Noguchi was “a real artist, a rare soul” and that he wanted to help him. He enclosed a copy of this letter of recommendation in a letter to Noguchi that once again begged him to come to Japan. The budget for the garden was only 2,500,000 yen, he warned. “I had to make the situation clear to you, no matter how discouraging. I want so badly to have you here—I have two or three jobs ready for you. One exterior sculpture for Nippon Gakki on the Ginza, another for a large fish refrigerating plant in Tsukiji etc. I know that I could never hope to make the Reader’s Digest site anywhere near as interesting alone, without you, as with you. You should be here now, blooming, there is so much to do, instead of vegetating in N.Y.”9 A letter of agreement dated January 30, 1951, stated that Noguchi was to be paid $1,500 plus airfare.

The modest offer came just at the right moment for Noguchi. Not only was this the perfect opportunity to learn more about gardens, but also he had fallen in love with a Japanese actress named Yoshiko Yamaguchi, whom he had met on November 13, 1950, at the opening of an exhibition of kimonos at the Brooklyn Museum.10 Yamaguchi arrived looking resplendent in a lavish kimono and three days later Noguchi’s friends Ayako and Eitaro Ishigaki invited Noguchi and Yamaguchi for dinner. When Ayako Ishigaki told her husband about her idea for this dinner, Eitaro approved. “Isamu likes glamour girls,” he said, “and there is a lot that Yoshiko could learn from Isamu.”11 In a clever maneuver, Noguchi arrived at the dinner early with a stack of Japanese magazines full of articles about his work. When Yamaguchi arrived—this time wearing a high-collar, Chinese-style, figure-clinging, floral-patterned dress—the Ishigakis were busy looking at the magazines, which she undoubtedly couldn’t miss. Fame was a necessary point in Noguchi’s favor: he was sixteen years older than Yamaguchi.

Nevertheless, Ayako spotted an electric charge between her two guests. “Sparks as bright as fireworks seemed to fly from the moment they looked at each other—Yoshiko with her big black eyes and Isamu with his severe gaze.”12 Perhaps Noguchi and Yamaguchi’s rapport had something to do with their recognition of each other’s underlying sadness. In spite of being blessed with beauty, talent, and success, both felt pulled between different cultures, he with his East-West conflict and she with a tension between her Asian upbringing and her acclimation to Western ways. Neither felt at home in their native country. Yamaguchi had spent her childhood in China and felt it was her real home. She knew she did not look particularly Japanese.13 “I was spiritually the child of mixed Chinese and Japanese blood,” she said, “and [Noguchi] was the actual child of mixed Japanese and American blood.”14 Years later Yamaguchi would remember that what drew her to Noguchi at that first dinner was the sympathy she felt in his voice when he said, “You must have had a hard time during the war between Japan and China.”15 “My heart pounded,” Yamaguchi recalled. “Why did this person know how I was completely torn between my motherland Japan, and China where I grew up? ‘I was troubled during the war between the U.S. and Japan as well,’ the person with gray-blue eyes said.”16

The war had indeed made trouble for Yamaguchi. The first child of Japanese parents, she was born in 1920 in Manchuria, which, when she was twelve, became a puppet state of Japan. Her father was employed by the South Manchuria Railway Company and taught Mandarin Chinese to railway employees. Yamaguchi went to a Japanese school until second grade and then to a Chinese school. When she was thirteen her father gave her as an adopted daughter to a pro-Japanese Chinese general who was also president of the Bank of Mukden, a city in Manchuria now called Shenyang. The so-called adoption was a customary way to seal a bond of friendship. In 1934 Yamaguchi was adopted by another of her father’s friends, who gave her the name Li Xiang-lan (pronounced “Rikoran” in Japanese) and who sent her to a missionary girls’ school. Wearing a Japanese kimono, she made her debut at age thirteen at the Yamato Hotel in Mukden. Her repertoire was mixed: Japanese songs as well as Schubert’s “Serenade” and Beethoven’s “Ich liebe dich.” After she graduated she became a popular actress and singer. Working for a film company backed by the Japanese government, she was usually cast as a Chinese beauty enamored of a Japanese soldier or sailor. Her Japanese identity was kept secret. By the war’s end Yamaguchi had been in some seventeen films, most of them pro-Japanese propaganda in support of goodwill between Japan and Manchuria, and, in the large scheme of things, in support of Japanese imperialism.

When the war was over Yamaguchi was arrested as a traitor by the Chinese authorities and threatened with execution by a local military council. After she proved her Japanese nationality, she was acquitted and ordered to leave Manchuria. In March 1946 she returned to Japan, took back her Japanese name, and gradually rebuilt her acting career. By 1950 she was a major film star. That year she played a Japanese comfort woman in Escape at Dawn and costarred with Toshiro Mifune in Akira Kurosawa’s Scandal. Also in 1950 the record in which she sang “Fragrance of the Night” was a hit in Japan. In April 1950 she went to Hollywood, where she took the name Shirley Yamaguchi and where, she told Time magazine, she wanted “to learn to kiss Hollywood style.”17 In addition to singing engagements in various cities, she was asked to star in King Vidor’s film Japanese War Bride. In New York she made a splash with the actor Yul Brynner, dancing at nightclubs and enjoying a celebrity-studded social life.

Soon after their first dinner at the Ishigakis’, Noguchi and Yamaguchi began to see each other every evening. “We walked together looking at many of his sculptures that decorated gardens in New York. I was astonished by his stage sets when I saw Martha Graham … This was the entrance to the world of Isamu … Alone, he challenged various contradictions between the East and the West and tried to push himself to the limit.”18 On their third date he asked Yamaguchi to marry him. She was surprised at the speed with which people did things in America.19 “When he proposed to me I wanted to continue dating,” she wrote in her autobiography. “So I had him wait for one year.” Later, they agreed to base their relationship on several conditions: neither of them should interfere with the other’s career and if their relationship had a negative effect on their work they would separate. Work often kept them apart. Sometimes this made their reunions all the more romantic, sometimes it created tensions.

In early March 1951 Yamaguchi left for Hollywood, where she signed her contract with Twentieth Century Fox, and then flew on to Honolulu en route to Japan. On his way to Japan Noguchi stopped in Honolulu too, and he and Yamaguchi spent twelve days at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel on Waikiki Beach. In late March he flew to Tokyo. Yamaguchi stayed behind for a singing engagement and joined Noguchi in Tokyo on April 21.

Noguchi was full of enthusiasm for the garden he was designing for Reader’s Digest, and pleased with his fee. He was also happy when, after the first phase of his Bollingen grant expired on December 21, the fellowship was extended for another six months.

During her first weeks back in Japan Yamaguchi plunged into singing engagements. A coloratura soprano with a bell-like voice, she had been trained as a girl by an Italian opera singer. She was also busy with record contracts and with negotiations for various Japanese film projects. On May 28 she returned to Hollywood to start work on Japanese War Bride while Noguchi and Hiroi stayed in Tokyo to work on the Reader’s Digest garden.

* * *

The area allotted for Noguchi’s Reader’s Digest garden was a little over an acre. He gave the space definition by creating earth mounds and a serpentine water channel shape that wound its way to several elliptical pools. The garden was conceived in the tradition of a Japanese stroll garden: as the visitor moved through it, it offered changing views. Rocks excavated from the site were placed with Zenlike care, as were dwarf bamboo, fruit trees, and large shade trees. At the end of the water channel, and rising from a rectangular pool, was a fifteen-foot-high fountain constructed of welded steel. The fountain’s openwork structure of five vertical elements connected by circles and arcs was not unlike his Bell Tower for Hiroshima and was similar also to his iron sculpture called Gakusei at Keio. For the garden as well, Noguchi made two four-foot-high semiabstract granite figures of a man and a woman. Influenced by Brancusi’s The Kiss, these figures are modeled on kokeshi, the traditional Japanese wooden dolls with large round heads and cylindrical bodies. The female is shaped like a vessel and has slightly swelling breasts and belly. Her oval head has Asian features. The male’s head has round Western eyes. To indicate that they are a couple, Noguchi gouged channels to represent fingers and arms locked in an embrace. The kokeshi could stand for Noguchi and Yamaguchi or perhaps for the meeting of East and West. Reader’s Digest rejected the doll figures and the pair is now in the Kamakura Museum of Modern Art.

“To do a garden in Japan is to bring coal to Newcastle,” Noguchi remarked, but the project allowed him to combine his knowledge of modernism with Japanese tradition.20 “Here was an opportunity to learn from the world’s most skilled gardeners, the common uekiya of Japan. Through working with them in mud, I learned the rudiments of stone placing—using the stones we could find on the site. There is to each stone a live and a dead side. They are placed according to rules of Shin, Gyo, and So; that is, the formal (Shin), the informal (So), and in-between (Gyo).”21 In his Bollingen manuscript he wrote: “I remember my contact with the earth when digging up five round stones. I experienced my first, almost ritual improvisation of placing them upon the earth with an exactitude that astonished me.”22

In June 1951, a few weeks before he finished his work on the garden, Kenzo Tange invited Noguchi to come to Hiroshima. Noguchi was drawn to Hiroshima: “I wished somehow to add my own gesture of expiation. The result was an invitation to submit designs for two bridges spanning the approach to ‘Peace Park.’”23

On his way, Noguchi stopped in Gifu, a city known for its cormorant fishing festival as well as for the fabrication of paper lanterns. He came for the festival, but Gifu’s mayor wanted Noguchi to revitalize the city’s paper lantern industry and to create designs that could be exported to the West. Noguchi was introduced to Tameshiro Ozeki, head of a family firm that had been making lanterns since 1891. After touring Ozeki Jishichi Shoten (now called Ozeki & Co., Ltd.), he decided to commit his paper lantern–designing efforts to this firm, with which he continued to collaborate for the rest of his life. Ozeki’s son Hidetaro, who runs the firm today, remembers the intensity with which Noguchi looked for the right lantern shapes. During his first visit, Noguchi was riveted by watching lanterns being made. Thin bamboo strips are wound around a wooden mold to create a spiral scaffolding onto which mulberry bark paper is glued. When the glue is dry, the mold is taken apart and removed. Noguchi was entranced with the mulberry bark paper, which looks delicate but is strong. Paper lanterns, he said, “appeal to the particular love of the Japanese for things ephemeral, like the cherry blossoms, like life.”24 In October he designed fifteen new lanterns, eliminating the traditional bent wood rims and designing various wire frameworks to hold the lanterns open and to make it possible to light them with electric bulbs instead of candles. “Presently this became like a cause with me—a new shape, merely, was not enough; it obviously had to be fitted into today’s new ways and uses.”25

On a late June afternoon, accompanied by Hiroi, who would assist him with the bridge rail project, Noguchi stepped down from the train at Hiroshima station. Reporters were on hand to greet him and the city had arranged for a bus to take him, Hiroi, Kenzo Tange, city officials, and members of the press to the site where the bomb had fallen. Photographers caught Noguchi’s look of horror held in check by disciplined reserve when he saw the destruction. Rising above the rubble at the blast center was the skeleton of a grand domed building that had housed the city’s Chamber of Commerce. Camera in hand, Noguchi moved through the devastated terrain. Hiroshima was, he recalled, “still empty of anything but the remains of destruction made even more poignant by the cleaned streets and an order which had been carried out leaving destruction on display, a catalogue waiting for the future.”26 The two bridges that needed railings were, he said, “still intact as to structure but with nothing above, nor railing. It is proposed that I might do these.”

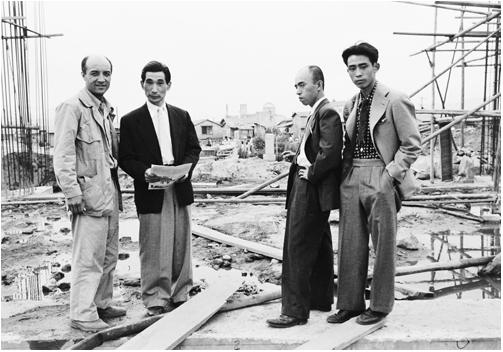

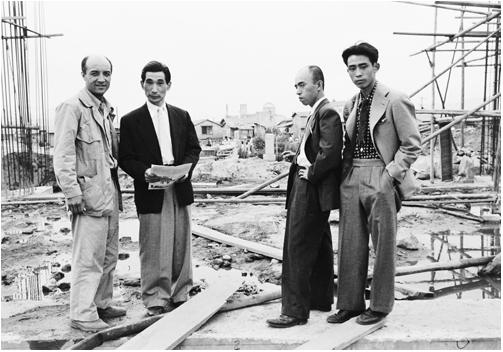

Noguchi in Hiroshima with Kenzo Tange, Tsutomu Hiroi, and, far right, Noguchi’s half brother Michio, 1951

In August Noguchi flew to Los Angeles to be with Yamaguchi as she worked on Japanese War Bride. The final approval for the bridge railings commission came just as he was about to leave Japan, and he designed one of the railings on the flight to Los Angeles. In Los Angeles Noguchi played second fiddle to Yamaguchi, but he did enjoy the glamour, which he also courted. He took her, for example, to a dinner party at Charlie Chaplin’s house in Beverly Hills, which impressed Yamaguchi very much. Noguchi managed to continue work on the Hiroshima bridge railings with his drawings spread out on Yamaguchi’s Twentieth Century Fox dressing table. The monumental finials at the ends of the cement railings symbolized life and death. One, thrusting upward and topped by a half-sphere with its face reaching up to the sun, was originally called “To Live.” The half-sphere may relate to Japan’s national symbol, the rising sun. The other, shaped like the ribs of a boat, was to have been called “To Die.” Later he changed the names to Tsukuru (To build) and Yuku (To depart). “The one that looks like a skeletal boat,” Noguchi said, “derives from the idea of the Egyptian boats for the dead—for departing, as we all must.”27

Noguchi’s bridge railing for Hiroshima, Tsukuru (To build), 1952

At summer’s end Noguchi and Yamaguchi moved on to New York, where they both met with critic Aline B. Louchheim, who was writing a piece on Noguchi for The New York Times. Noting Noguchi’s pleasure in working on public projects in Japan, Louchheim observed: “The sculptor has broken from the imprisonment of a solitary studio. His new place of work is the world.”28 Noguchi once wrote that during this eight-month sojourn in Manhattan, he was “filling in the time while Yoshiko worked.”29 In fact he was working on two projects. One was a playground for the United Nations Headquarters in Manhattan, a commission that had come from his friend Audrey Hess, wife of the critic Thomas B. Hess, who had written such a positive and insightful article about Noguchi for Art News in 1946. The other project was an interior plaza or sculpture garden on the ground floor of the dazzling new Lever House, a glass-fronted office building on Park Avenue designed by Gordon Bunshaft, chief architect at Skidmore, Owings and Merrill.

Audrey Hess had approached Noguchi about the playground commission before he left for Japan to work on the Reader’s Digest garden. By June 1951 Noguchi, still in Tokyo, was working on his concept for the playground and was conferring by mail with architect Julian Whittlesey, with whom he was collaborating. On August 7, back in the United States, Noguchi met with the project’s sponsors, including Audrey Hess, Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, and Mrs. David Levy (Hess’s aunt). The sponsoring group raised $75,000 to pay for a 100-by-140-foot playground to be built northeast of the UN building.

Noguchi designed a play landscape with a grotto, a jungle gym, a multitiered structure for climbing and sliding, a wading pool, swings, and triangular hills in bright colors. There were tunnels and winding paths and round hollows filled with sand. As always, there were mounds. Both the UN’s architect, Wallace K. Harrison, and the UN plan director Glenn Bennett were enthusiastic, but Robert Moses, the man who had thwarted Noguchi’s Play Mountain, was not impressed: “If they want to build it, it’s theirs, but I’m not interested in that sort of playground,” he said. “If they want us to operate it, it’s got to be on our plans. We know what works.”30 Noguchi heard later that Moses had threatened not to put safety railings along the East River if the playground was built.31 Not surprisingly, the UN succumbed to Moses’s pressure and agreed to build instead a conventional playground of the type that Moses approved.

The rejected playground became a cause célèbre in art circles. When in mid-April the Museum of Modern Art exhibited the plaster model together with some of Whittlesey’s drawings, it described the UN playground as “the most creative and imaginative play area yet devised.”32 In a short piece about it in the April issue of Art News, Thomas Hess extolled the playground’s beauty and its integration of modern art and daily life. “Perhaps this is why it was venomously attacked (‘a hillside rabbit warren’) by the Cheops of toll bridges.”33 This Cheops, he noted, had “no legal or moral right to dictate the UN’s aesthetics.” According to Hess, plans were under way to find an alternate site for the playground. Noguchi left for Japan in early May, leaving Whittlesey to deal with the project’s collapse.

During the fall and winter of 1951, Lever House, Manhattan’s first major building to use a glass curtain wall, was still under construction on Park Avenue at Fifty-fourth Street, but Noguchi was able to work there on his model for the building’s plaza, which he said was to be an “oasis of art.”34 The Lever House commission was the beginning of a long and fruitful collaboration with Gordon Bunshaft, who played a leading role in the transformation of European modernist architecture from its utopian beginnings to its function as an expression of corporate pride.35 Born to Russian Jewish immigrant parents in 1909, Bunshaft graduated from MIT with a master’s degree in architecture, and in 1937 joined Skidmore, Owings and Merrill. He was taciturn, no-nonsense, and sometimes gruff. Most of the time he and Noguchi got on well—but both were famous for their lack of patience and their total focus on work. In 1968, having completed six projects with Bunshaft, Noguchi wrote: “The architect with whom I have worked most is Gordon Bunshaft … It is due to his interest that projects were initiated, his persistence that saw them realized, his determination that squeezed out whatever was in me. I am beholden to him for every collaborative architectural commission I have been able to execute in the United States (with the exception of the Associated Press Relief and the ceiling and waterfall of 666 Fifth Avenue).”36

One reason that the two men worked so well together was that Bunshaft recognized and respected the role of the artist in relation to architecture. Of the Lever House project, Bunshaft said, “We hoped to have sculpture integrated with the total design, including landscape, and Noguchi was the only sculptor that I knew of in the world who had the requisite knowledge of architecture, of plant material and of space design.”37

Inspired by the white sand gardens of Kyoto, Noguchi planned to cover the Lever House plaza with white marble “from which would rise sculptures with small risings and apertures in the marble for planting.”38 The plaster model that he made during his stay in New York had a small version of Mu in one corner, and, rising from a circular reflecting pool, three columnar sculptures—abstractions of a man, woman, and child.

On October 16, while the Lever House project was in the stage of receiving quotes for the various elements, Noguchi and Yamaguchi announced their engagement. They then flew via London to Paris, where Noguchi introduced Yamaguchi to Brancusi. Brancusi gave her an appraising gaze and led her to a revolving table upon which stood his polished bronze Leda covered with a cloth. He pulled off the cloth and set the table turning so that Leda was bathed in fluctuating light. Yamaguchi recalled that she was so taken by the sculpture’s beauty that she wept for the happiness of being alive.39 From Paris Noguchi and Yamaguchi drove to Italy, the next leg of their planned month of traveling in Europe and in India. They reached New Delhi in November. Noguchi wanted to share his passion for India with his fiancée, but Yamaguchi was horrified by the poverty and filth. They visited Nehru in order for Noguchi to show him his plans for the Gandhi memorial that they had discussed two years before.

On November 16 Noguchi flew to Tokyo from Manila and Yamaguchi went to Hong Kong to negotiate a possible role in a Chinese film. When he arrived at Haneda Airport, both his and Yamaguchi’s families, plus the press and some of Yamaguchi’s friends and business associates, were there to meet the newly engaged couple. A group of chorus girls from the Nichigeki gave Noguchi a bouquet, but the welcomers were disappointed that Yamaguchi was not there. She arrived in Tokyo the following day, and reporters noted that she was wearing a Noguchi-designed kimono made of navy blue fabric covered with x’s and o’s—hugs and kisses. Their wedding was planned for mid-December. Yamaguchi wrote in her autobiography that she and Noguchi had agreed to have homes both in the United States and in Japan.40 This way they could be together as much as possible, but they could also pursue their respective careers.

In late November Noguchi traveled to Hiroshima with Kenzo Tange to see how the construction of the bridge railings was going. Noguchi, Tange, and Hiroshima’s mayor discussed the possibility of Noguchi designing a memorial to those killed in the bombing. The structure was to hold an underground tablet upon which the names of the 110,000 victims of the American bomb would be recorded. Tange and the mayor saw no problem in having an American design the memorial. It was, after all, meant to have meaning for all mankind, not just for the people of Hiroshima. Noguchi agreed to do it free of charge as an “expiation of our mutual guilt.”

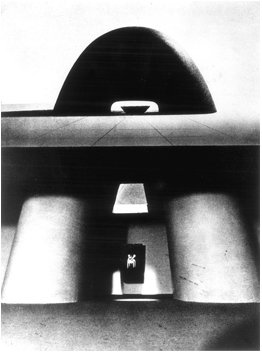

Noguchi worked out his model in Tange’s Tokyo University office and described his cenotaph design as “a cave beneath the earth (to which we all return). It was to be a place of solace to the bereaved—suggestive still further of the womb of generations still unborn who would in time replace the dead. Above ground was to be the symbol for all to see and remember … a mass of black granite, glowing at the base from a light beyond and below.”41 What Noguchi envisioned aboveground was a heavy, bell-shaped granite arch with its ample legs growing wider toward the bottom and continuing below ground level. Between these legs, in an underground room, the names of the dead would be placed in a granite box cantilevered out from the wall. In comparing the part beneath the earth to a womb, he acknowledged the relationship of his memorial to a female figure with two great protective thighs. Thus, as with many of Noguchi’s sculptures, the theme is, in part, fertility. Noguchi also associated the granite arch that loomed above the underground cavern with the shape of the atomic blast. And it probably alluded also to John Donne’s tolling bell. Another connection was with haniwa, whose cylindrical forms are echoed in the massive granite thighs and which were likewise associated with death. Noguchi saw the arch as an “ominous weight.”

Noguchi’s model for his Memorial to the Dead, Hiroshima, 1952. Plaster. Lost

In the following month Noguchi worked on his model for the cenotaph with the fervor of someone driven, perhaps not only by a sense of complicity, but also by the demons of his childhood, his conflicts about East versus West, father and mother. Somehow his idea of who he was seemed to ride on the creation of this emblematic monument. It was as if the Hiroshima memorial rooted Noguchi himself in the Japanese earth, the “protective abode” that he had always looked for.

According to what Noguchi wrote for Bollingen, he was in Hiroshima working on the memorial when the date for his wedding was set. “I was informed of my imminent marriage to Yoshiko. Surprised but not displeased, I rushed back to Tokyo to the congratulations and the preparations of an event for which I was totally unqualified.”42

Noguchi and Yamaguchi were married on the morning of December 15, 1951, at the Meiji Shrine. There were no guests at the Shinto ceremony. One can imagine the couple walking along the broad gravel path that curves through an evergreen forest, passes under torii (gate structures), finally arriving at a huge courtyard. From the shrine they proceeded to the home of the painter Ryuzaburo Umehara, who served as the nakodo, or go-between. Here they exchanged wedding cups of sake. In the evening there was a party at the Hanya En, a traditional Japanese restaurant in a beautiful garden. When the couple arrived, they were met at the Hanya En gate by crowds of reporters, photographers, and curiosity seekers. Among the forty-odd guests were the filmmaker Akira Kurosawa and his lead male actor Toshiro Mifune, opposite whom Yamaguchi had played in Kurosawa’s Scandal. Also present was Nagamasa Kawakita, president of Towa Film Company and the man who had intervened with the Chinese authorities in 1945 when Yamaguchi was threatened with execution as a war criminal.

The bridal couple made their way through the throngs of reporters and into the restaurant, where they kneeled in front of a gilt-covered folding screen. Noguchi wore traditional formal Japanese attire, a dark kimono with pantaloons and a tunic. Yamaguchi wore a Noguchi-designed white silk kimono with an obi in a checkerboard pattern. Both carried folded fans and both wore Japanese sandals and tabi socks. Before the banquet began, the imperial Gagaku musicians played their ancient music. The newlyweds moved among the guests, welcoming them with a few words. The banquet was eaten on low lacquer trays, with the guests seated Japanese-style on the floor. Noguchi must have wanted to cement their union with an American marriage, for three days later they were married again at the American embassy in Tokyo. Even his wedding was a cross between East and West.