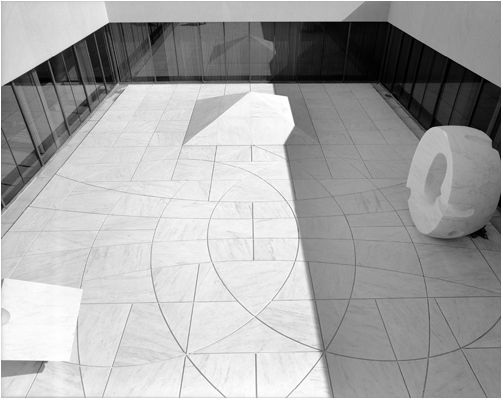

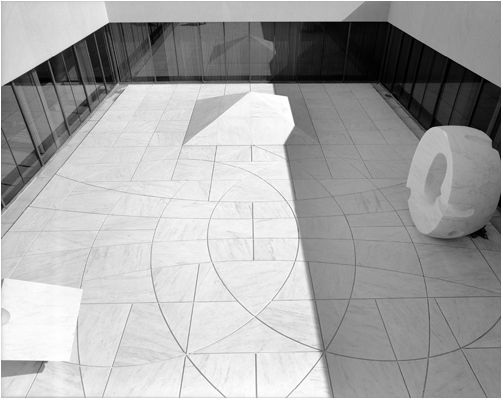

Installed in his new Long Island City studio in the early 1960s, Noguchi was fired by the idea of creating sculptures that would be “a vital function of our environment.” For Yale’s Beinecke Library, a rectangular structure with a grid of gray granite framing translucent white marble panels, he proposed a sunken white marble garden with, instead of plants, three marble shapes—a ring, a pyramid, and a cube balanced on one point. The garden feels cerebral, detached from the world, thus suitable to the library site. Its sunken space is framed above by a band of pale granite and below by glass walls that allow library users to look out onto it. Although at first glance the garden’s three shapes look precise and geometric, their proportions are slightly off, in keeping with Noguchi’s Zen-inspired predilection for asymmetry. He wanted what he called “a non-Euclidian garden concept.” Thus, for example, the circle’s vertical axis tilts and the hole that gives it a doughnut shape is off center. The pyramid’s sides are unequal and the cube is not quite a cube. Noguchi wanted the three shapes to reverberate with energy, to “call to each other.”1 “And pretty soon, there’s a kind of hum because of this vibration that is occurring between objects and between the spaces and presently there is a kind of magnetic gyration into which you are then caught.”

Beinecke’s seemingly pure shapes have a source in the astronomical gardens he had admired in India and in Zen gardens with their white sand cones emerging from a sea of raked white sand. The pattern of curved and straight lines formed by the cracks between the floor’s marble sections likewise looks back to raked sand. Inspiration came also from paving patterns Noguchi had seen in Italy. “You can notice,” Noguchi said, “that the lines on the marble ground give a kind of perspective, in a sense like the Frontier stage set. It opens up. I have often used the ground artificially—that is to say, I think of the ground not just as ground but as a kind of geometry of ground.”2 His garden was an imaginary landscape, “nowhere, yet somehow familiar. Its size is fictive, of infinite space or cloistered containment.”3

Noguchi waxed poetic about the meaning of the three marble shapes. The pyramid, he said, suggests the earth, the past, and infinity. The cube “signifies chance, like the rolling of dice … the cube on its point may be said to contain features of both earthly square and solar radiance.” The circle is the sun. “The symbolism of the sun may be interpreted in many ways; it is the coiled magnet, the circle of ever-accelerating force. As energy, it is the source of all life, the life of everyman—expended in so brief a time … Looked at in other ways: the circle is zero, the decimal zero, or the zero of nothingness from which we come, to which we return. The hole is the abyss, the mirror, or the question mark.”4

Garden for Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale, 1960–64. Imperial Danby marble (© Ezra Stoller / Esto)

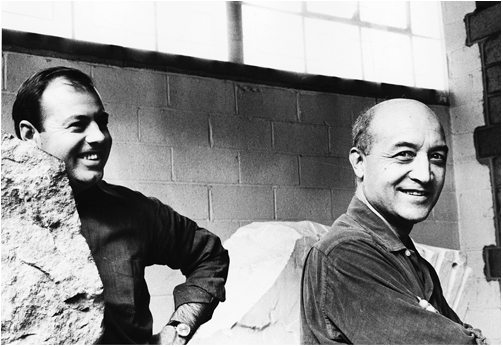

For the Beinecke job Noguchi had the help of a young Texan sculptor named Gene Owens, then head of the art department at Texas Wesleyan College. They had met in 1961 when Noguchi was in Fort Worth working on his sculpture for the First National City Bank building plaza. In August 1962 Owens went to New York to meet with Noguchi, and in the next years he worked with him on six different occasions. The letters Owens wrote to his wife, Loretta, while he was in New York are almost like a diary.5 The first, written just after he arrived in Manhattan, said that Noguchi’s Italian bronzes were about to arrive and would need work. In the meantime he and Noguchi were casting some bronzes at the Modern Foundry and working on the bases for sculptures. Noguchi, he said, would then need help on the Yale job as well as on the playground for Riverside Park. In what is probably his second letter (the letters are often undated), he told his wife that Noguchi had said he enjoyed having him there as a stimulus to work. “I am an audience to him, he said, and you must work for your audience. He said he would slow down once I left but he was going to get the most out of me while I was here. I believe him. But I don’t mind it. I wouldn’t like it otherwise really…”

What must be Owens’s third letter, written around March 18, reveals some of the difficulty he experienced in working for Noguchi. “Today went fine I guess, but I am about to go mad … Talk about spic and span, boy!” It appears that Noguchi was almost fetishistic about keeping his studio in order. “The chisels were lined up on the shelf,” Owens recalls.6 Once I picked up one of them to use and Noguchi grabbed it. ‘Brancusi gave me that one,’ he said.” During the day, as Noguchi and Owens moved from one sculpture in progress to the next, Noguchi insisted that the tools used on the sculpture they had just set aside be put away, even if they might return to that piece later. Gene reported to Loretta: “A germ hasn’t got a chance in that place.”

To prepare for a visit from Gordon Bunshaft, Owens made a cast of a small model for Beinecke. In a letter postmarked March 19 Owens told Loretta about a battle that ensued when Bunshaft told Noguchi that he should give Beinecke’s sun disk a more elaborate, more baroque shape, and Noguchi refused: “I saw and heard him tangle with an architect from Skidmore Owings and Merrill. Boy it was like a lion and a tiger fighting. The architect told him not to talk to him like he was something from Greenwich. He said one of [Noguchi’s] little models looked like a Lifesaver. Isamu gave him hell. They would settle down and then go at it again. There was no place for the sensitive artist in that little transaction. It would have crushed me but not Isamu. He knows he is right.”

Noguchi and Gene Owens in Noguchi’s Long Island City studio, 1960s

Noguchi and Owens frequently dined with Priscilla. The first time that Owens met her she gave him the impression of being “obviously very wealthy and important politically.” Over the years he came to recognize the strength and complexity of her bond with Noguchi: “Their relationship was strange. I don’t know why she put up with it. It was obvious they liked each other. He didn’t love her. He thought the world of her. I don’t think that he ever had a relationship with a woman as close as his relation to Priscilla … Every time I went up there Priscilla was doing something for Noguchi which he wasn’t capable of doing for himself.”

During his first dinner at Priscilla’s, the assembled company talked about collecting and Noguchi said that he didn’t see why anyone would want to collect. The idea of possessions appalled him. “You see,” Noguchi told Owens, “this is why I like to do architectural things; because they are not in anyone’s possession really. They belong to the whole public.” At this point in their friendship, Owens’s impression of Noguchi was that he was “quite a complicated person in a nice way and I want to understand him more. I think there is more wisdom than one is aware of right off. He is certainly a businessman. 60% or more of his day is taken up with letter writing, clients, telephones (he lives on the phone—both phoning and being phoned). Every night is used to politic—but his politicking is a form or serves as his amusement.”

At times Owens grew frustrated with Noguchi’s stubbornness and his ineptitude with certain technical problems like fabricating a small tool to screw a piece of threaded brass into a recessed area—a task that would have taken Owens ten minutes alone but resulted in days of toil under Noguchi’s worried watch. When Noguchi could not solve a problem he would distract himself by making phone calls. “He is the only sculptor I know that builds things with a telephone: Sculpture By Noguchi, built with a telephone … He has to completely dominate any one around him. I rather suspect that is my purpose.” Sometimes the two men would jump into Noguchi’s car and seek help from some technically savvy person like Edison Price. In the afternoons, the two would rest and have tea. “At this time Isamu would become very meditative for about ten minutes then pick up the phone and take care of several business calls. Then we would sit and talk and have tea.” Often they listened to music.7

Noguchi’s habit of second-guessing was another irritant. Owens would be drilling a hole and Noguchi would keep interfering and then try to do it himself, do it wrong, and then when Owens pointed out the right way to do it, Noguchi would do it that way and then say that it was his idea. “The point is he personally is never wrong. He has all the confidence in the world.” For all his criticisms, Owens admired and loved Noguchi rather as a son loves a difficult father: “He is strong as a horse, stubborn as a mule and has the energy of a 10 year old. He is as good a businessman as you’ll find. The best politician I have ever seen and a damned good sculptor.”

Owens’s next stint with Noguchi was in August 1963, after Noguchi returned from working on commissions in Italy, Israel, and Paris. Again, he found Noguchi almost unbearably stubborn. On August 30 Owens and Noguchi drove up to the IBM site in Armonk, taking with them the model for two terraces that Noguchi had designed. In the next few days they planned to install the stones for the Chase Manhattan Bank’s water garden. Owens wrote:

I swear I don’t know if I can take another minute of Mr. Noguchi. Today I started on the plaster for the molds. We had discussed doing them earlier and I had suggested making it in several pieces and then making a mother mold to hold the pieces in place. He said that wouldn’t be necessary and was very adamant about it. Well I let it go but this morning he said as though we had never had a previous conversation that it would be best to make a shell to hold the pieces together. After I got the two pieces made and a mother mold to hold them in place he looked at it and said it needed handles. I put the handles on which added about 100# to the weight. He then thought that the middle needed strengthening. He was still uncertain as to it being strong enough when I assured him that he could drive his car over it he seemed satisfied but then when we went to move it it was tremendously heavy and he bitched and complained about it being so heavy he kept saying, ‘Oh that’s way too heavy. You shouldn’t have made it so heavy.’ Everybody but that egotistical bastard is wrong.

In the following days Owens and Noguchi put in long hours, working straight through the Labor Day weekend with Owens making molds according to Noguchi’s instructions, instructions that Owens often knew were wrong.

Toward the end of his stay in New York, Owens, worn out from hard work, wrote Loretta that he had no news, just “bitching about Isamu and his ego. But really he goes out of his way to get along with me…” Owens and Noguchi continued to work together from time to time and they kept in touch over the years. On a trip to New York in February 1965 Owens went out to the Long Island City studio and when he rang the bell he heard a commotion on the other side of the door. Noguchi opened it and said, “I’ve hurt my foot.” While going to the door he had stumbled over an unfinished stone sculpture and broken his fibia at the ankle. Owens drove Noguchi to a doctor. As there was no nurse, the doctor told Owens, “You pull on the foot while I hold the leg.” When Owens heard the bone snap into place he almost passed out, but Noguchi laughed. The doctor put Noguchi’s leg in a cast and for the rest of his time in New York Owens became Noguchi’s “nurse, chauffeur, assistant, and constant companion.”8 In the evenings Noguchi introduced him to artists, including Claes Oldenburg, George Segal, Ad Reinhardt, Ibram Lassaw, Herbert Ferber, Frederick Kiesler, and Louise Nevelson.

Perhaps it was during this visit that Owens and Noguchi went to a gallery and saw one of Andy Warhol’s 1962 paintings of multiple Coke bottles. “Then suddenly Isamu said, ‘Gene, we have got to go to the Metropolitan Museum. There’s something I want you to see.’ The piece in question was a Buddhist shrine made of stone. The inside was lined with hundreds of little Buddhas seated in a meditating position. ‘Oh, I see,’ I said. ‘The Buddhas are like the Coke bottles in Warhol’s Coke bottle painting.’ Isamu grinned. ‘What do you suppose Andy was praying to?’ Isamu asked.”9