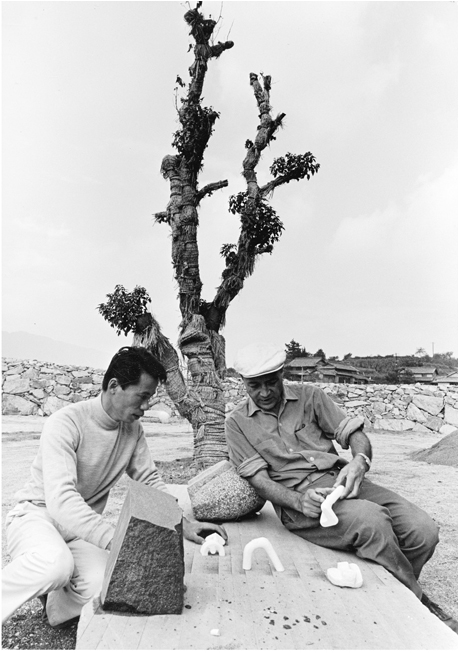

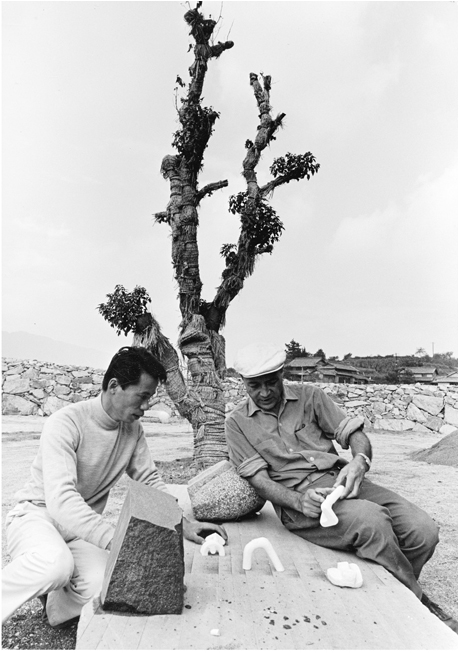

For the rest of Noguchi’s life, Masatoshi Izumi would be like an extra pair of arms and hands. He was an extra pair of eyes as well, for he seemed to understand what Noguchi had in mind, and he carved Noguchi’s stones with patience even when Noguchi was agitated. Completely devoted, Izumi made Noguchi’s life in Japan function smoothly just as Priscilla took care of the details in New York. Izumi hired and supervised the assistant stonecutters. He helped Noguchi select rocks on stone-fishing expeditions. He took him to different quarries. He ordered stone from various sources and made sure that it was delivered to Mure. When sculptures were finished he often arranged for their shipping. Izumi and Noguchi also enjoyed moments of leisure. Izumi would organize lunches at local noodle shops, and he and Noguchi and sometimes Okada would dine together. Izumi also accompanied Noguchi on swims. He would take Noguchi to new spots and they would swim far out into the sea. In the evenings he would arrange for Noguchi’s dinner. His wife, Harumi, or a housekeeper would cook and Izumi and Noguchi usually ate together.

Stone fishing was the highlight of Noguchi’s life on Shikoku. Izumi was amazed at Noguchi’s avidity when they visited quarries or searched the land for rock. “We went to Shodoshima Island, to Okayama, and to Sweden, where the quarry was a deeply dug out place like a black cave. Noguchi was always very excited. He had the instinct of an animal about finding a good place to find stone.”1 Once Noguchi told Izumi that he wanted to look for stones on the small island of Okinoshima off the southwest tip of Shikoku. They traveled to Kochi and from there took an afternoon boat to Okinoshima. Since there was no hotel room available, they stayed in a fisherman’s house, where they shared a fish for supper. Since the island had no roads, the following morning they rented two boats, one large and one small, to search the coast for stone. Because of a recent typhoon the waves were nineteen feet high. “Noguchi and I left the bigger boat and took the smaller one in order to get close to the coast. When we were about twenty feet from the rocky shore, the boatman said ‘we cannot get closer in the boat.’ So Noguchi and I swam toward the coast. Noguchi was a very good swimmer, but I was not. I wondered if I would get home alive. When we reached the shore we could not hold on because there was slippery moss on the rocks.” Finally the two men gave up trying to get a purchase on the rock and they swam against the waves back to the boat. When Izumi heaved himself into the boat Noguchi was already safely aboard.

Noguchi working in the stone circle at Mure, Shikoku, with Masatoshi Izumi, 1970

On their quarry visits, Noguchi’s hunger for stone was sometimes in conflict with his fear of spending money. He would order a large number of stones and later, full of buyer’s remorse, he would cancel part of the order. Realizing that it would be hard to replace the canceled stones and that Noguchi would eventually find a use for them, Izumi would telephone the quarry and restore the full order. “Noguchi hated to waste money,” Izumi says. “He would want three or four stones, but I would go and buy a boatful of stones—seventy of them. Noguchi was amazed.” Acting as Noguchi’s patron, Izumi’s family’s stone company paid for the stones. “The stones were for the sake of Noguchi’s work,” Izumi says, and Noguchi’s work was the most important thing in Izumi’s life.

Noguchi had a genius for attracting people like Izumi, Priscilla, and Shoji Sadao, who could make his life run smoothly. Harumi and Masatoshi Izumi soon became his surrogate family. Noguchi was also close to the Ukita family, who owned the mannari granite quarry and stoneyard in Okayama Prefecture, where Noguchi had first gone in search of granite for UNESCO’s fountain stone. Takashi Ukita, who runs the company now and whose grandfather ran it when Noguchi first came there, recalled that Noguchi was like a gentle grandfather: “But once he started working his eye became so sharp and strict that a small child could not talk to him. The atmosphere was tense. When he confronted a stone he did not draw on it immediately. He’d draw in chalk for a few days, then he would not start carving until he had a plan.”2 When Takashi’s older sister came to the worksite to tell Noguchi that lunch was ready, she would not say a word. Noguchi would ignore her until he felt ready to break for lunch. “You are very patient,” he would say.

Every day Takashi Ukita’s mother, instructed by her father-in-law, cooked different Japanese delicacies for Noguchi, who would always protest. “Just a rice bowl is enough. Today you don’t need to work so hard.” Takashi was astonished to see how clean this man’s plate was after eating. Mrs. Ukita also escorted Noguchi to local places of interest. She took him, for example, to a large Japanese-style garden in Okayama and pointed out to him a mannari stone monument, which had been broken because it was too large to move. The pieces had been reassembled into a huge, dolmenlike stele with the cracks still visible. The technique, Mrs. Ukita explained to Noguchi, is called wari modoshi, which, loosely translated, means “cut and put back together.” In the late 1950s, using this technique, Noguchi made a sculpture for the Ukita family, and, starting in 1968, he made a number of sculptures, such as This Place and Another Land, that are assembled out of the split pieces of a single stone. The play between the lines formed by the cracks and the stone’s undulations and texture is always exquisite.

When Takashi Ukita was old enough, he and Noguchi would go swimming. “Noguchi loved to swim. He’d swim way out. It scared us. He liked to swim in several different places on the same day. He didn’t even dry himself. He just got into the car to go to the next swimming place.” Once Takashi and Noguchi were swimming far from shore and Takashi said they should swim back, but Noguchi, ever intrepid, said, “I never think about returning.”

Starting in 1969 Noguchi made a home and studio on the island of Shikoku, spending half a year there, usually three months in the fall and three months in the spring. Out of fitted rocks he built the stone circle work space. Gradually the circle was populated by Noguchi’s stone sculptures, each one quiet and still but emitting a mysterious energy. Since Noguchi was reluctant to part with his best works, the circle became not just a workplace, but a kind of outdoor museum.

No matter how perfect the working conditions, Noguchi grew restless if he stayed in one place for too long. During Katharine Kuh’s 1960 interview she asked whether he wanted to go back to Japan, and Noguchi had said: “Of course I want to, but I would get lonely there. I would miss certain kinds of communication—the contact with other artists’ thinking which encourages me to follow the sequence of my own thoughts.”3 When Kuh visited Mure in 1973 she noticed that Noguchi “seemed to relax, expand, and belong there, to relinquish the tensions that usually drove him.” Still, she recognized Noguchi’s feeling of never being at home anywhere.4 Noguchi told her: “When I’m in Japan, I think I should be in the United States, and when I’m there I want to be back in Japan.”5 But by this time, Kuh observed, Japan appeared to exert “the stronger pull.”

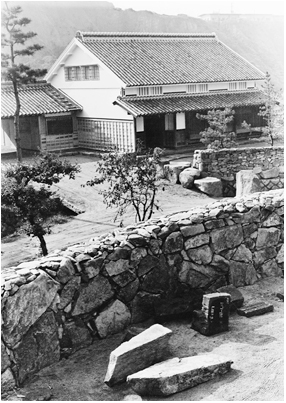

Before he had a dwelling on the site, Noguchi would stay in a hotel in Takamatsu, and Izumi would pick him up in the morning and take him to Mure. In 1970 he finally had a residence built at the bottom of a steep hill and just across the road from the stone circle. His architect friend Tadashi Yamamoto had been told by Governor Kaneko to look for a place for Noguchi to live close to Izumi’s stonecutting workshop. Yamamoto found an eighteenth-century house that had probably belonged to a merchant or a tradesman, but that had the nobility of a samurai house. It was due to be demolished. “So I had the idea to move it and reassemble it here,” Yamamoto recalled.6

Izumi and a master carpenter named Shinkichi Dei went to see the house. “It was spooky,” says Izumi. “It leaked and the framework for the shoji screens was broken.” But Shinkichi Dei judged the beams and posts and some of the plaster walls to be in good shape. Noguchi was less enthusiastic. He did not want to live in a ghost house, he said. In spite of Noguchi’s reluctance, Yamamoto decided to take it apart and rebuild it on Izumi’s land. “Gradually,” Izumi recalls, “Noguchi began to like the house.” Shinkichi Dei was hired to rebuild the house according to Noguchi’s taste. The walls and partitions were either shoji screens or adobe walls composed of earth, oil, and straw. Following Japanese tradition, the layout allowed for a flow between inside and outside. Noguchi could sit on a tatami mat and gaze out at his garden through open shoji. With his respect for Japanese tradition, Noguchi used no glass windows, only paper shoji. But he insisted that the house should be light inside. Also he wanted certain modern conveniences. To heat the house hot water pipes were installed beneath the gray stone floor of the front room. On cold nights additional heat came from a brazier. Noguchi kept a television and a record player hidden behind wall panels on the first floor. The slightly raised living room was covered with tatami and partitioned off by shoji. Whenever Noguchi arrived on Shikoku, he would put down his suitcase and lie down on the tatami mat. “This is what I need,” he would say.7

Noguchi’s house in Mure, Shikoku

All the rooms were spare—Noguchi was allergic to the idea of decoration and most objects were kept out of sight. Furnishings consisted of old chests, baskets, and straw stools. Noguchi’s Akari perched where needed or hung from the ceiling, as did a Balinese percussion instrument that looked like a primitive xylophone. Here and there Noguchi’s sculptures emanated their quiet energy. Wave in Space, a slab of black granite whose surface swells like a wave, graced the floor of the front room. Increasingly after Noguchi set up his Shikoku studio, he made low-lying sculptures that were a continuation of the landscape/table sculptures that began with This Tortured Earth. The rounded top of Wave in Space is polished and shiny. Below, where the wave moves up out of the surrounding water, the stone is pitted. In this respect Wave in Space is like an expanded version of Origin (1968), carved from the same black African granite, but Origin’s roundness is more visceral and makes one think of tumescence and birth, whereas Wave in Space evokes the movement of water.

In the back of Noguchi’s Mure house a veranda overlooks a small, very private bamboo grove. Here Noguchi placed Ground Wind, which he carved in 1969, a dark stone that snakes about twelve feet across the earth. Inspired perhaps by the sections in a stalk of bamboo, its length is made of several sections. Noguchi left Ground Wind in Mure: “I thought it too Japanese to come here [New York]. It looks perfect where it is. So I made Ground Wind # 2—an abstraction, where the other is more real.”8 A photograph shows Noguchi dressed in a kimono and kneeling in his back garden beside Another Place (1968), a roughly square black granite slab broken and reassembled. Eventually weeds grew in the sculpture’s cracks and Noguchi, who cared very much about how his sculptures were maintained, moved it to his Long Island City studio.

Noguchi’s house had a kitchen in a new addition and a bathroom with a traditional Japanese tub. Leading from the entryway to the second floor is a steep stairway enclosed by vertical wooden railings. The railings on the second floor landing allowed Noguchi to see who was coming before the arriving person could see him. “As a rule, Isamu didn’t like guests,” Yamamoto recalled.9 Noguchi’s bedroom on the second floor has a tatami-covered, raised platform enclosed by a shoji screen. Here at bedtime he would roll out his futon. Next to the bedroom Noguchi’s study is furnished with Western appurtenances such as bookshelves, a desk, and two chairs.

At Mure, as in Kita Kamakura, Noguchi allowed his Japanese side to flourish. After his evening soak in his Japanese tub he donned a yukata (cotton kimono). Seated on a pillow on the floor, he ate Japanese food. “A Japanese would never live this way,” he said. “I can do it because I am not Japanese.”10 Noguchi’s lifelong struggle to resolve the East-West conflict energized not only the creation of a perfect place at Mure, but also the sculptures that he produced there.

Noguchi shaped his Mure compound as a work of art. It was the haven that he had always sought—a place where most of what he looked at and touched was of his own choosing. Dore Ashton wrote, “His life’s work, as he often said in later years, was about creating an ‘oasis.’”11 His art, he told Ashton, was not about making objects but about creating spaces and forms connected with life. “I wanted to reach what may be defined as a way of life, a space of life, or even a ghetto closed and defended from the world.” Closed and defended—very much like Noguchi himself. In spite of his urbanity and charm, Noguchi, fearful of chaos and emptiness, increasingly anxious about the passage of time, pursued his search for identity by making art and by creating a home. He told Dore Ashton’s husband, Matti Megged, in 1985: “I think that artists are always making a place of security for themselves, you know. Their studio becomes their home, their museum.”12 But even with his beautiful Shikoku oasis, Noguchi could never settle down. “No matter how comfortable I am I simply can not stay in one place for a long time.”13

Over the years Noguchi added to his compound two large antique storage houses, or kura, that had the robust simplicity and perfect proportions of Greek temples. The inside walls of white adobe mixed with straw supported a wooden latticework. Round posts set on round stone bases held up splendid crossbeams and a tiled roof. One kura became Noguchi’s studio for when he wanted to work indoors. The other, a former sake warehouse, served as a repository for finished sculptures.

Photographs of Noguchi at Mure tend to show him either confronting a rock or sitting looking contemplative. He also liked to have fun. Besides lunches and dinners with friends, there were visits to nearby temples and shrines. He tried never to miss traditional festivals such as the three-day Obon, a Buddhist celebration to honor the spirits of ancestors. Houses are cleaned, offerings to the dead are made, and lanterns are lit and carried to graves. Sometimes lanterns with candles inside are floated down a river to send off ancestors’ spirits. Noguchi would join in the Bon-Odori folk dance and dance in the street for hours. Often after attending Obon he would visit Taiko Okada at his Buddhist temple in Sanuki city near Takamatsu. Okada remembers walking with Noguchi in the nearby cemetery and Noguchi’s surprise seeing the bamboo frame of a lantern that had lost its paper. Among the graves, Noguchi noticed broken statues of Jizo, a beloved bodhisattva devoted to the protection of travelers, pregnant women, and children, including dead children. Noguchi picked up one of the broken heads and took it with him.

In the graveyard Noguchi also asked to see the tomb of a legendary pearl diver named Ama, who, according to Okada’s telling of the story, had retrieved a pearl from a dragon king who had stolen it and taken it to his underwater home. Pursued by the dragon, the diver cut open her breast and put the pearl inside. She managed to swim to the surface with the pearl, but she died of her wound. It was a story Noguchi spoke of often, and in 1982 he made a sculpture called The Mermaid’s Grave.

Okada, who frequently talked about religion with Noguchi, thought that Noguchi was very much involved with Buddhism. (Noguchi once said that the closest he came to religion was Shinto—he loved the way Shinto imbued nature with spiritual value, the idea that trees and rocks were the abode of deities.) “Noguchi believed in the mystic power of the mountain,” Okada says.14 On one occasion Okada told Noguchi that it was arrogant to break and make art out of the ancient boulders that he had had transported to his stone circle. Okada’s reproof embarrassed Okada’s brother-in-law, Yamamoto, and Governor Kaneko. But Noguchi told Okada: “I agree with you.”15