While at Henraux in the summer of 1971, Noguchi received a call asking him to participate in a competition for a fountain for Detroit’s Civic Center Plaza, an eight-acre area overlooking the Detroit River. The late Anna Thomson Dodge (widow of the automotive pioneer Horace Dodge) had made a generous bequest—$2 million—for building a fountain that was to be a memorial for her husband and son. As Noguchi told the Walker Art Center director, Martin Friedman, “To spend $2,000,000 on a fountain isn’t easy … and, besides, I wasn’t interested in making the type which the donor had specified, such as the Barcelona Fountain with a lot of jets going up all over the place in a circular area. I wanted to make a new fountain, a fountain which represents our times and our relationship to outer space.”1

Mrs. Dodge’s will had given Detroit a September 1 deadline and time had nearly run out. Not wanting to forgo the money, the city hastily organized the competition. The eleven-member Horace E. Dodge Fountain Selection Committee’s hope was that the fountain and plaza would help revitalize Detroit’s derelict downtown, which in recent years had been the site of protests and riots. Noguchi’s plan was selected before the deadline. A letter of agreement between the city of Detroit and Noguchi dated August 16, 1971, indicates that in mid-June the city’s Common Council had authorized disbursements from Mrs. Dodge’s bequest so that Noguchi could be paid twenty thousand dollars to come up with a fountain design, including sketches, written material, cost estimates, and renderings.

Six days before the deadline, Noguchi submitted his proposal to the fountain selection committee. His submission included diagrams of basic types of water effects. He turned up the heat on the rhetoric of persuasion:

The great fountain, projected as the most magnificent of modern times, rises from the plateau of primal space. It is an engine for water, plainly associating the spectacle to its sources of energy—the engine—so closely a part of Detroit. It recalls and commemorates the dream that has produced the automobile, the airplane and now the rocket. The fountain rises 18 feet into the air, hovering in a cloud of water, incandescent at night.

The fountain will be an engineering feat in metals.2

An early drawing of Noguchi’s fountain shows a bridgelike structure that is clearly based on Japanese ceremonial gates. In the center of this long elevated structure Noguchi planned to have a steel ring thirty feet in diameter spouting water up and down and supported on hefty granite piers. Below the fountain, a circular granite basin would spout water upward, interacting with the ring’s downward flow. The surrounding area was to be lined with paving blocks set in sand. Given the “many imponderables,” Noguchi said, it was difficult to be certain about cost. But he gave an estimate of $400,000.

Two days before a probate court deadline for satisfying the execution of the Dodge will, Noguchi’s design was chosen. But a court battle ensued because Mrs. Dodge’s architect grandson, who had submitted his own design to the competition, maintained that Noguchi’s fountain was not in the place his grandmother had stipulated, which was “at the foot of Woodward.” The following July the court ruled that the fountain’s proposed site, now relocated closer to Woodward Avenue, did not contradict Mrs. Dodge’s wishes.

Horace E. Dodge Fountain, Detroit, 1972–79. Stainless steel, ht. 24 ft.

As with several other projects, Noguchi, having won the competition, enlarged the scope of his work by asking to design not just the fountain but the entire plaza. Robert Hastings, chairman of the fountain selection committee, and also head of the architectural firm that had done the initial design of the plaza, accepted Noguchi’s request. Over the next eight years Noguchi became passionately engaged with Detroit’s Civic Plaza, for which he designed not only a fountain but also a twisting pylon. He was eager to make a “gateway to the city,” a place where people from all walks of life could connect. The plaza, he hoped, would revitalize downtown Detroit, calm political tensions, and perhaps even reverse the flight to the suburbs. This would not, he said, be just a beautiful sculpture, it would be useful. The need he felt to make something that would become part of people’s lives arose, he thought, from his need for belonging. “If through art the world can be made more friendly, more accessible to people, more understandable, more meaningful, then even art has some reason.”3

The Dodge Fountain required elaborate engineering, which Noguchi’s partner Shoji Sadao and various consulting engineers worked out.4 Noguchi himself liked to solve technical problems and his attention to detail was extraordinary. He would make site visits and take note of everything that was not as it should be—things like the exhaust and fresh air intake stacks, the lighting, the placement of feeder pipes, the position of fog nozzles, the spacing of jets, the height of jetting water. He even invented his own hydraulic nozzle, which produced a cylindrical column of water hollow at its center.

In March 1973 Noguchi presented to the Common Council a revised design for a “cloud-creating” computer-operated fountain, which he said would evoke “a bird rising” as well as “an airplane and jet propulsion.”5 He also presented a plan plus scale model for the plaza with its stainless steel pylon, which made a quarter turn as it moved upward. The plaza would serve Detroit’s public by offering a range of activities, including an amphitheater that could be converted into an ice skating rink. There were various pyramids to hide mechanicals and to serve as seating areas. On the day following the presentation the Detroit Free Press reported: “Pixyish Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi, his eyes gleaming as he moved his shiny aluminum pointer from model to diagram to architect’s drawing and back again, told Detroit’s Common Council Friday what the new $18 million riverfront plaza will look like.”6 It would, Noguchi promised, be “different and better than” New York’s Rockefeller Center or Lincoln Center. “It will be a people’s park, not a monument.” The fountain, which was now to be all stainless steel and twenty-four feet high instead of eighteen feet as originally planned, would have eighty different water and light patterns.

Noguchi kept changing his mind about certain aspects of the design. He had to convey these changes to Sadao, who had to communicate them to the consulting engineers, who were not always pleased at the change orders. On September 16, 1973, he wrote to Priscilla, “So I keep writing to Shoji and he tries to placate feelings all around and diplomatically translate my diatribes into acceptably polite and reasonable requests. Its [sic] probably just as well that I am far away.”7 Noguchi’s irascible mood had also to do with his not being able to work on his own sculpture, which, he told Priscilla, was “utterly displaced and I’m distressed that I can not seem to get going.” Work on the Detroit plaza did not go smoothly. By the time the project was completed, for all his pride in it, Noguchi had some sour feelings about his years of struggle—delays, lawsuits, the city government’s inefficiency, arguments, cost-increasing changes, and mistakes. At one point, for example, when they tested the fountain the force of the water was so strong that a large chunk of the granite basin blew out. Noguchi’s relationship with Coleman Young, Detroit’s first African-American mayor, had testy moments. Soon after Mayor Young was elected, Noguchi recalled, “He saw what we were doing; our models, our plans and so forth. The first thing he said was, ‘Well where’s the ethnic festival?’ You see, the ethnic festival was something that had been going on for years along the river.”8 In fact, Noguchi had not planned for an underground space large enough to accommodate the festival, but without hesitating he told Mayor Young that the ethnic festival would be downstairs. He now went back to the drafting board and designed a two-acre area beneath the plaza. The mayor’s question, Noguchi said, expanded the underground space from a skating rink and amphitheater to a covered performance area, gallery, restaurant, and room for twenty-six kiosks.

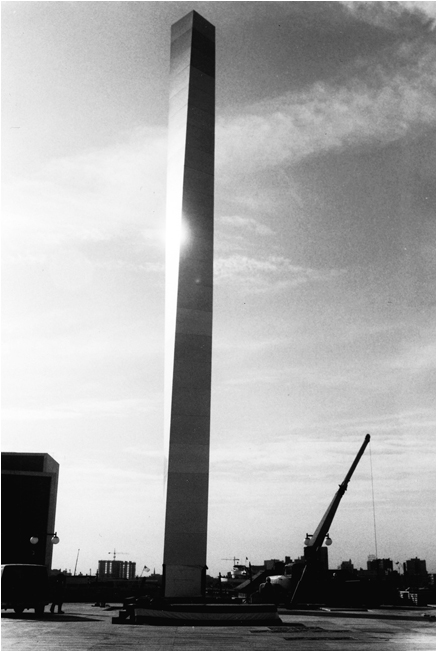

With Mayor Young presiding, the twisted pylon was dedicated on August 28, 1974. “This distinctive landmark,” Young declared, “is a big step in developing an outstanding people-oriented, riverfront-downtown area.”9 Noguchi said that the pylon with its quarter turn signified the “spiral of life, the double helix on which all life is based.”10 “It was nothing I did. It was done by nature originally.”11

Construction of the Dodge Fountain began in 1975 and it was dedicated on July 24, 1976. The fountain’s ring, twenty-six feet in diameter and often described as a doughnut, is held aloft by two splayed cylindrical legs that can be seen as a high-tech revisiting of the idea of the female giving birth seen in Noguchi’s 1952 memorial to the dead of Hiroshima. The water from the circle jetting downward between heavy thighs might allude to water breaking. A Detroit Free Press writer took note of the primal associations in Noguchi’s fountain and pylon: “The pylon is the energized phallus,” she suggested. “The fountain is a receptacle, the … legs shape the delta, with the same kind of sensuality that characterized prehistoric fertility goddesses.”12 Likewise, the Detroit News critic noted that the fountain’s cylinder and ring shapes were the “timeless forms of birth and regeneration,” all appropriate symbols of Detroit’s rebirth.13

Noguchi’s Philip A. Hart Plaza was dedicated on April 20, 1979. Thousands of people gathered, many toting picnic bags. The fountain went through its repertoire of effects and sunshine created rainbows in the upward-spurting spume. The dedication by Mayor Young and Noguchi was preceded by a jazz band concert, a mime-troop performance, and the twenty-six-member Baptist Church choir all dressed in mustard-yellow robes singing “I Love This Place” as the crowd swayed and clapped. Then came speeches. “You now see before your eyes, beneath the shadow of the Renaissance Center, the new Detroit,” proclaimed Mayor Young as the crowd in the five-hundred-seat amphitheater clapped and whistled. “This is a marvelous people place.” Noguchi smiled and waved his arms. When it was his turn to talk he said: “This enormous beautiful spot didn’t look like much when it was a parking lot. But it’s turned out better than ever I could have imagined.” He said he had nothing to add to what had already been said: “I’ve spoken through the fountain.”14

Pylon for Philip A. Hart Plaza, Detroit, 1974. Stainless steel, ht. 120 ft.

For all the euphoria on the day of the plaza’s dedication, there were, for Noguchi, things that rankled. The trees, bushes, and grass he had planned had not yet been planted. Many technical problems had not been solved. The day before the dedication, at a City Council award presentation ceremony at which he was the honored guest, Noguchi saw fit to complain about the “unconscionable” maintenance of his fountain. The water had been left on during the winter and the pipes froze.15 He urged the council to hire permanent maintenance.

Noguchi’s public criticism didn’t sit well with Mayor Young, who responded that dedicated and permanent maintenance wasn’t in the budget. Nonetheless, when the two of them left the award presentation Young had his arm over Noguchi’s shoulders.16 Within a week of Noguchi’s departure from Detroit, the planting had begun and the fountain was working, but not at its full capacity. The fountain continued to be plagued with technical problems in the years to come, and in 1987 the Detroit Renaissance Foundation raised $800,000 to renovate it.

In spite of the frustrations involved, Noguchi was proud of his work in Detroit. It was his most ambitious project so far, and since many of his plans for public spaces had fallen through, its completion meant a great deal to him. He felt that the fountain and plaza had done much to revitalize downtown Detroit. But he was also worn down by the project. In an interview with The Detroit News a few days before the April 20 dedication, he expressed a desire to return to private sculpture: “I will concentrate on just my own work. That way, if I just stop moving around, I could probably find a much happier life. I crave a sense of place.” Yet Noguchi’s unstoppable creative energy kept him crisscrossing the globe. “I have an unfinished road to walk,” he told an interviewer in 1985. “By the time I approach something, I’m off on another mile.”17

* * *

For all his desire to focus on carving stone, even before the Detroit plaza’s dedication, Noguchi was considering a number of public commissions. Kukaniloko (1977) was a proposal (unrealized) to protect the sacred Hawaiian “birth rocks” from the encroachment of pineapple crops. In 1978 he began to design the Lillie and Hugh Roy Cullen Sculpture Garden for the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, and in 1979 he began to think about Bayfront Park in Miami. There was also an unrealized sculpture garden for the Tennessee Williams Fine Arts Center in Key West.

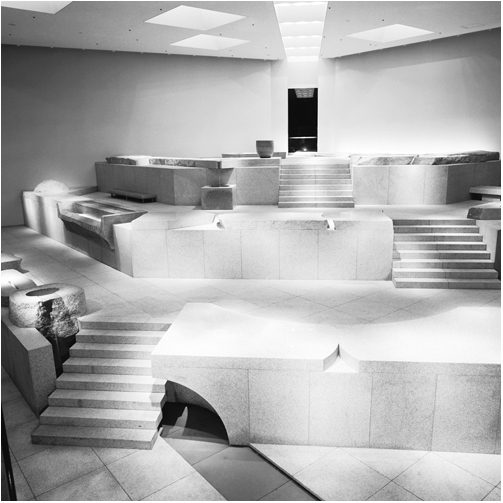

Heaven, interior garden at the Sogetsu Flower-Arranging School, Tokyo, 1977–78. Granite

One of the most successful of these commissions, an interior garden for the display of flowers at Tokyo’s Sogetsu Flower-Arranging School, was called Tengoku, or Heaven. Noguchi’s old friend Sofu Teshigahara, the avant-garde flower arranger and painter who was master of the school, asked him to design the lobby of the newly built, eight-story, glass-skinned school building designed by Kenzo Tange. Tange had already designed the lobby, but Teshigahara was not satisfied with Tange’s solution, so he told Tange that he would like to ask Noguchi to redesign it. Tange’s response was measured and calm: “Is that so? I understand.”18

On October 13, 1975, Noguchi wrote to Tange that he had sent a model of his lobby to Izumi, who would carve it out of stone. The space was peculiar because the upper balconies of a theater on the floor below projected into the lobby in a stepped sequence, or, as Noguchi put it, “like a ziggurat.”19 Noguchi’s solution was to design what he described as “a stepped hill of stone, a place for people to go.”20 He compared the space he created at Sogetsu to a giant tokonoma, which he said was “the most sacred spot in a Japanese house … It’s heaven, and what I’ve done there [at Sogetsu] is heaven, you see.”21 The result was a wonderfully alive, many-tiered mountain made of pale granite blocks interspersed with the occasional rough-hewn boulder. The whole space is united by the subtle downward flow of water from a basin on the upper terrace. The stream first drips into a stone tsukubai (basin), and then continues downward, sometimes disappearing and reappearing. Although the total volume of Heaven’s space is small, it feels as majestic as a mountain, and, because of the skillfully arranged lighting with skylights on the ceiling, you feel, looking upward, as if you were being led into the firmament. Outside the building is a thirty-foot-high, slightly twisted, black granite pylon, which Noguchi compared to the ritual post that sets off a tokonoma in traditional Japanese houses.

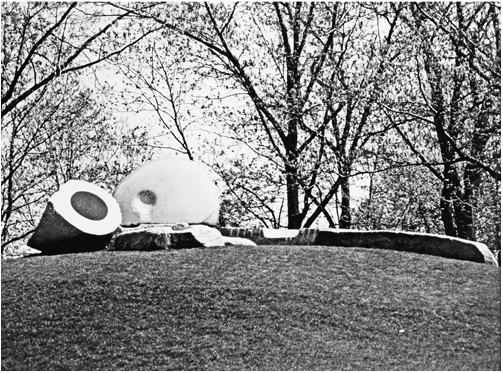

Yet another brilliant commission from the second half of the 1970s was for a sculpture for Storm King Art Center, a sculpture park in Mountainville, New York. Here Noguchi created a grouping of pale granite rocks that is one of his greatest and most loved sculptures. Designed to be climbed upon, Momo Taro is warm and welcoming in its embrace, more accessible than most of Noguchi’s works, but no less mysterious.

According to Peter Stern, president of the Storm King Art Center, when he visited Noguchi to discuss the project, Noguchi marched him through a studio full of metal sculptures. Stern told Noguchi that he wanted a sculpture made of stone. Noguchi gave Stern a noncommittal look and asked, “What drawings do you need?” Stern said, “None.”22 This pleased Noguchi, who explained that he didn’t want to make a careful model for his sculpture because “anything precise restricts you.” Noguchi asked Stern where in the park his sculpture would be placed. Stern said, “Anywhere you like.” Noguchi, who tended to choose prominent sites, picked a grassy knoll close to the administration building overlooking the vast rolling park. Noguchi asked if he could make the hill bigger and alter its profile. Starting in 1933 with his giant earthwork Monument to the Plow, Noguchi had had an urge to sculpt the earth. This too was agreeable to Stern, and backhoes soon appeared to do the job.

Momo Taro, Storm King Art Center, Mountainville, New York, 1977–78. Granite, nine elements

On June 13, 1977, Noguchi wrote to Stern that he would proceed with the project and outlined a verbal agreement. He said he planned to look for suitable stones that summer in Japan, and he would be “listening to what they say.” Noguchi had hoped to use pink mannari granite, but it was too expensive, so he settled upon granite from the island of Shodoshima. Years later he told the story of finding Momo Taro’s stone: “It was the night time when I climbed the mountain on the island of Shodoshima, where Izumi had spotted a huge stone. Too big to handle, it was broken in two to get it to my studio. Is it from these stones that my concept came, or is it not more correct to say that it derived equally from the hill at Storm King?”23

The title Momo Taro comes from a popular Japanese folk tale that Noguchi’s mother had often recounted to him. A childless couple discovered a giant peach floating down a stream. When they picked it out of the water a miraculous child emerged. He grew up to slay the local dragon.24

Noguchi saw that the two pieces of the split boulder resembled a peach cut in half with the pit removed. Since he identified Momotaro as the child of the sun god, the round, split-open boulder could also stand for the sun. To complicate matters further, in Noguchi’s mind his sculpture had to do with the Japanese creation myth.25 The upturned stone on the left was, Noguchi said, not only the sun but also “a mirror, a reflection.”26 The split rock’s cavity opening up toward the sky might also have suggested to Noguchi a womb for light. He told Dore Ashton that Momo Taro was “a place to go … a metaphor for man as an end and a beginning … a mirror to the passage of the sun.”27 Perhaps the boulder’s two halves with their round cavities refer to procreation, while the seven flatter, more rectangular stones lying close by refer to life’s end.

The way Momo Taro hugs the grassy hilltop makes it seem as if it were embracing the world. “I’m very much attached now to closeness to earth, sinking into it,” wrote Noguchi.28 But he also felt that the sculpture was playful. When in October 1988 Noguchi visited the site, he said, “I want children around that sculpture. It’s made for children.”29 Momo Taro is perhaps the most engaging play object that Noguchi ever made. It brings out the child in every visitor. During Noguchi’s October visit, a little girl crawled out of the hollow of the peach, held out her hand to Noguchi, and asked him to join her in the peach’s cavity. He went in and when he emerged his face was wet with tears.