Noguchi was a genius at shaping water in relation to stone to create a feeling of both instantaneity and timelessness. The water flowing down the UNESCO garden’s steps is an early example. His 1984 water garden for the Domon Ken Museum in Sakata, Japan, is another. The sparest of Noguchi’s gardens, it consists of rock, water, and a clump of bamboo. A sloped area, partly enclosed by architect Yoshio Taniguchi’s museum building, is shaped by broad granite steps over which water cascades into a pool below. Noguchi stood a single basalt rock on the third step from the top. In a more literal explanation than was usually his wont, he said that the flowing water symbolized the passing of time and that the rock was the photographer Domon Ken, standing in the middle of the flow.

Perhaps Noguchi’s most beautiful use of water is in the garden he created in the early 1980s in Costa Mesa, California. The garden was jointly commissioned in 1980 by the Prudential Insurance Company of America and Henry Segerstrom, an Orange County art patron and developer of the South Coast Plaza Town Center, a business and cultural complex situated not far off the San Diego Freeway. The site Segerstrom had in mind was a 1.6-acre space squeezed between two fifteen-story glass-facade office buildings and a forty-foot-high parking garage. Late in 1979 Segerstrom flew to New York. As planned, he arrived at Noguchi’s Long Island City studio at 9:00 a.m. He rang the bell and told the voice that answered that he had come to see Noguchi. The voice, which turned out to be that of Shoji Sadao, said that Noguchi was home in his Manhattan apartment with a cold. Segerstrom persisted: “Well, I’ve come from California and I have a flight leaving this afternoon.” Sadao invited Segerstrom to come inside out of the freezing cold. Moved by the beauty of the sculptures he saw, Segerstrom begged Sadao to call Noguchi to ask if he could come to show him the site plans for the possible garden commission. At Noguchi’s 333 East Sixty-ninth Street apartment, Noguchi and Segerstrom looked at the plans for the Costa Mesa site. “He said he didn’t like it,” Segerstrom recalled, “and objected to the presence of so many cars. Why didn’t people walk, as they do in New York, he wanted to know. I tried to point out the virtues of the project, but he was not receptive and his cold seemed to give him a more negative attitude.”1

Segerstrom returned to Orange County disappointed but not defeated. He wrote Noguchi a flattering letter, further expressing his “dream” of bringing Noguchi’s art to the plaza.2 A month and a half later, Tamara Thomas, a Los Angeles art consultant, wrote to Noguchi telling him what an “ideal client” Segerstrom would be. She did not exaggerate. When Noguchi finally capitulated, he got on better with Segerstrom than with any other patron. There was a deep bond of sympathy between the two men, and the garden that resulted from this connection was all the more perfect because of it. Thomas told Noguchi that Segerstrom had envisioned “a very soft green landscape area” at his Costa Mesa site and she was astonished at Segerstrom’s willingness to accept Noguchi’s “bare plaza” concept.3 Noguchi wrote back on January 25, 1980: “I am indeed intrigued with your client” and his “ambition to go beyond what has been done before.”

Later that year Noguchi went to see the site in Costa Mesa. He looked askance at the undistinguished corporate buildings and a garage flanking the space allotted for the garden, but his respect for Segerstrom and his desire to do something in his native state persuaded him not to turn the project down. “I said I wouldn’t do just a sculpture; the area needed more than that. Mr. Segerstrom agreed, but he didn’t know what he was getting into. I made a plan for the garden as a sort of menu. I wanted to do it all, but I didn’t expect him to buy it all. One does not expect that much support.”4

In mid-February Tamara Thomas wrote to Noguchi that she and Segerstrom understood Noguchi’s desire only to take on projects that gave him the possibility of “exploration and growth.”5 It was, she said, this attitude that made Segerstrom want to work with him. On March 28 Segerstrom wrote to Thomas: “Noguchi has agreed!” He said he wanted Noguchi to create a sculpture as well as the courtyard. “I would like to have in our project not only the expression of Noguchi’s mind but also of his hand.”6

On July 18 Tamara Thomas sent Noguchi a letter of agreement that included the sculpture, which at that point was to be called Origin Stone. Noguchi was to be paid $250,000, fifty thousand more than he was paid for JACCC’s To the Issei. His prices were going up concomitant with his increasing fame. He told the Los Angeles Times art critic Suzanne Muchnic: “I decided if I was going to do the project, I wanted to do something for all California—its water, desert, power and agriculture. I wanted to get down to the essence of these elements and effect a congealing of things, which is the way of sculpture. I wanted to show the process by which water comes from a source and ends up as energy and to address the problem of industrial incursion … California as the original paradise has been transformed … Maybe we destroy natural charm when we impose ourselves. This garden is a sort of soliloquy on why the situation is the way it is.”7

When the Two Town Center building that flanks the garden was still under construction Noguchi visited the site again. Seeing earth being moved must have whetted his appetite for rocks. On August 1, 1980, he wrote to an official at the Joshua Tree National Park asking if he could remove five rocks from the park and place them in his garden.8 His request was denied. It was against National Park Service policy to remove rocks. So Segerstrom chartered an airplane and he and Noguchi, together with Segerstrom’s son Toren and the project’s consulting landscape architect, Kenneth Kammeyer, flew all over California looking for stones. They finally found the right ones in Yucca Valley near Joshua Tree National Park and in Arizona.

On Noguchi’s next trip to Costa Mesa, when Segerstom picked him up at the airport and told him that he had arranged for him to make his presentation to a group of architects and construction people working on Two Town Center, Noguchi said, “No Henry. I want you to see it first. I want you to see it alone.”9 So they drove to Noguchi’s hotel, where the sculptor opened a suitcase and pulled out an approximately twenty-by-twenty-inch board upon which he had drawn the elements he planned to include in the garden. He placed several small models in their locations on the board. “Now this is an abstract representation of the geology and geography of the State of California,” he said.10 He then described how each element would work with the others. “Isamu, what do you call this?” Segerstrom asked. California Scenario, said Noguchi. He chose the word “scenario” to allude to Southern California’s film industry. Segerstrom told Noguchi that his design was “absolutely perfect.” Noguchi, Segerstrom realized, “had a singular ability to translate the scope of a universe the size of the State of California into symbolic elements that could be placed in a small-scale area. So the die was cast. There was no redesign.”

In November 1980 Segerstrom, his wife, Renée, and Toren visited Noguchi on Shikoku. There they saw the fifteen large pitted granite boulders that were cut on their inner sides so that they would fit together to make the sculpture destined for California Scenario—a sculpture whose name had now changed from Origin Stone to The Source of Life. The Segerstroms watched as the stonecutters put the boulders together and then took them apart again for remitering to get a better fit.

Early in 1981, using a crane, Noguchi, together with two master stonecutters from Japan and the staff of Kammeyer’s firm, assembled the twenty-eight-ton, ten-foot-high sculpture over the course of two weeks. He now named the piece The Spirit of the Lima Bean in honor of the Segerstrom family, which had been the nation’s largest independent producers of lima beans until the mid-1960s, when they converted their land to commercial and residential development. “At first,” Segerstrom recalled, “I thought he was teasing me … I think he changed the name out of respect for our friendship and our ability to work together.”11 Noguchi said that The Spirit of the Lima Bean “gives continuity to the history of the spot, its previous use, a sense of time and place.”12

As the garden progressed, Segerstrom talked through many aspects of the design with Noguchi, to whom he always deferred. He allowed Noguchi to make some expensive changes in the plantings and in the way the water in the stream flowed. He even helped to move the project along when Noguchi was elsewhere. Looking back two years after the project was completed, Noguchi said, “A rare individual who abetted all this with warm personal involvement was Henry Segerstrom, and I am grateful.”13

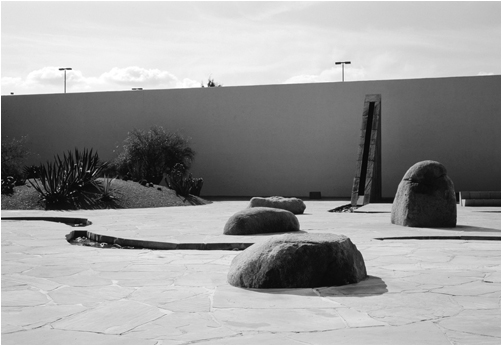

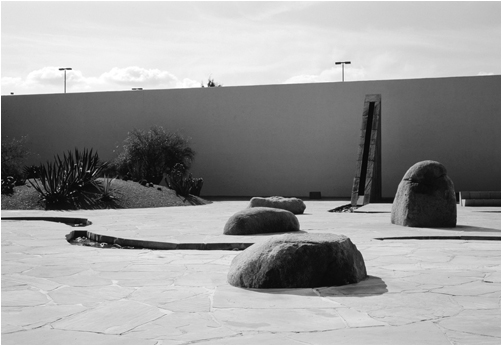

California Scenario consists of six elements that refer to California’s environment plus The Spirit of the Lima Bean. The elements are (1) Forest Walk, a grove of redwoods beside a horseshoe-shaped white granite path; (2) Energy Fountain, a cone faced with granite and topped by a stainless steel cylinder from which water spurts upward to suggest California’s dynamism; (3) Land Use, a coffinlike block of white granite set on an eight-foot-high knoll covered with honeysuckle—this might refer to the misuse of land because of industrial development, but in a letter Noguchi put a more positive spin on it: “Memory recognizes ‘Land Use,’ a passage of life and a testament to those who made America”;14 (4) Water Source, a tall, triangular form made of sandstone with water flowing down a channel cut into its face and into a meandering stream; (5) Desert Land, a circular mound covered with sand-colored pebbles and planted with native Californian cacti and other desert plants; and (6) Water Use, a polished white granite pyramid into the base of which the meandering stream disappears.15

In creating a garden full of symbols, Noguchi was following Japanese tradition. The six elements in California Scenario were, Noguchi said, meant to create a tranquil setting that was an abstract evocation of California. The peacefulness is there—spare, quiet, and Zenlike. But so is a vitality that comes from the perfection of each element’s placement and from the way one element relates to the next, either by contrast (organic versus geometric, hard versus soft, dark versus light, wet versus dry) or by the overall harmony of all the different materials. Noguchi preferred, he said, to work not with a single thing but with relationships between things, because they “gather energy between them and talk to each other.”16

California Scenario has the exquisite simplicity of the Beinecke garden, but, for all its precision and restraint, it is much more human. As in a Japanese stroll garden, the visitor’s movements are carefully orchestrated. We are gently led across the sandstone terracing, stopping at one element and then the next, all of them enlivened by the sparkle and gurgle of water. Embedded deep into the sandstone terracing, the rocks—some vertical, some recumbent—speak quietly to the geometric shapes nearby, creating a dialogue between nature and human intelligence. What is astounding is the way this small courtyard enclosed by glass-walled office buildings and the white plastered walls of the garage is made to feel limitless. It is a beautiful example of the artist’s childlike ability to imagine vastness within tiny places and to encapsulate eternities of time within an instant. The viewer, too, can imaginatively transform the space, so that, for example, the triangle out of which water emerges is like a distant mountain and the meandering stream seems to be a wide river cutting through a canyon. The white pyramid into which the stream disappears could be as big as a pyramid in Egypt. The enclosed space pulls us into the poetry of Noguchi’s symbolic world. It may be an oasis of peace, but it also emanates a mood of loneliness that underlies much of Noguchi’s best work.

California Scenario, Costa Mesa, California, 1980–82

As always, Noguchi was extraordinarily scrupulous, even obsessive, in his attention to detail. His letters to Kammeyer and to Segerstrom discuss everything from the joints in the sandstone paving to the number of barrel cacti, to the design of the trash baskets and cigarette stands. “As with everything else,” he told them, “my conscience won’t let me abandon responsibility even down to this latest stub disposal.”17 At one point he wrote to Segerstrom that he was not satisfied with the way the water flowed in the stream. He recommended removing the jets from the stream and replacing them with a four-inch feeder line that would wind its way under the sandstone paver ledges. He wanted “babbling effects” in certain parts of the stream; these, he said, could be created by invisible three-inch-high dams. Another time he wrote that an additional filtration tank was necessary to produce a surge of water out of the base of Water Source.

Noguchi also paid close attention to his compensation. He tended to overreach when it came to what he should be paid—possibly this had to do with his general feeling that his sculpture was underappreciated. His propensity to ask for more money than stipulated in his contracts can perhaps be understood if one remembers the poverty Noguchi had endured in his youth. On December 8, 1981, he sent Segerstrom a bill asking for $130,000 more than was agreed upon in his original contract. His justification was that extra work was needed for all the garden’s elements, as well as for his designs for benches, stone tables, light source stones, garbage receptacles, and cigarette stands. Segerstrom’s response was sympathetic, but he explained that there was no further money to be had. Part of the funding had been provided by the Prudential Insurance Company, which was unwilling to pay anything more.

Noguchi wrote back to Segerstrom on April 2, 1982, that when he had signed the contract he had already done his overall design for California Scenario, and that he signed it in spite of the fact that it seemed unfair to him because it tied him to the realization of every detail. He did this, he said, because “I was interested in leaving in California something significantly beautiful which I knew could not be done except with the equal interest which I perceived to be yours … But how is one to decide what is fair? After all this is my profession and means of sustenance. I may be blamed for having enticed you. What is the role or process of art if not continuous development and refinement from vague beginnings to the clarity of its final exposition? Nothing may be known in advance nor can contracts be defined ahead in legal terms without getting in return the kind of response that is seen everywhere in architecture, design, or the art[s] which are minion[s] to the commercial world.”18 Years after the garden was finished, the money issue still rankled. When Segerstrom wrote to Noguchi in 1986 about making a film about California Scenario, Noguchi replied that he would collaborate with the filmmaking if Segerstrom could convince Prudential to pay the bill for the extra work.

California Scenario was inaugurated in mid-May 1982, and Segerstrom managed to persuade Noguchi to stay for half of the four-day celebration. Suzanne Muchnic’s story on the opening in the Los Angeles Times said that there was “enough pomp circumstance, food and drink to daunt serious socialites.”19 The celebration was justified, she said, for California Scenario was, to her mind, “the most ambitious, absorbing and successful outdoor sculpture in the area.” Allan Temko wrote that Noguchi’s garden was “one of the 20th century’s supreme environmental designs … [an] oasis of high philosophic splendor.”20 Artforum called Noguchi’s garden a “stately oasis with its quiet assertion of human values.”21 Many of those closest to Noguchi say that he considered California Scenario to be the best garden he had designed. Other times Noguchi said that it tied as favorite with the Billy Rose Sculpture Garden. Much of the pleasure he took in this project had to do with the gentlemanly, extraordinarily supportive patron who helped him at every turn. In his museum’s catalogue Noguchi wrote that in creating his garden he and Segerstrom had “a true confluence of interest [which] is evident in its resolution. Would it have been the same working for an insurance company?”22