In the days leading up to the Biennale’s opening, Noguchi lunched every day with his entourage, which included Shoji Sadao and his wife, Tsuneko; Priscilla Morgan; Glimcher and his wife; and a young Japanese couple, Kyoko and Junichi Kawamura, both of whom had become central to Noguchi’s life in the last few years. Every night there was an elegant social gathering, one of which, hosted by Glimcher’s Pace Gallery, was a dinner for two hundred people at the “Antique Garden” of the Cipriani Hotel. “It was on the ground floor, right on the water,” Glimcher recalls. “There were paper lanterns. It was beautiful and Noguchi had a good time.”1 Glimcher was surprised that when Noguchi and his group of friends walked around Venice, Noguchi would walk ahead with beautiful Kyoko Kawamura while her husband, Junichi; the Sadaos; the Glimchers; and Priscilla would trail behind. If Priscilla minded, she was too proud to let on.

The night before the opening, Noguchi was guest of honor at a party cohosted by the Peggy Guggenheim Museum and the American consul general in Venice. An artist friend hurrying to get to the party on time ran into Noguchi with the Kawamuras going fast in the opposite direction.2 Noguchi, it seems, did not want to be feted. The Grand Prize had not yet been announced, but since it was generally known that he was not going to win, he probably felt some chagrin. On the other hand he may have fled from social contact because, as Izumi recalls, two of his front teeth had just broken. His health had not been good in the last year, and he was feeling old and restless, as if time were running out. Kan Yasuda recalls that at a seated dinner party for four hundred people at the American pavilion, Noguchi stood at the podium when it was time for him to say a few words and, after noting that the goal of the Venice Biennale was collaboration between artists of different ethnicities, said, “I am half Japanese, you know.”3 Then he left the stage. Noguchi left Venice for Pietra Santa early in the morning on June 29, the Biennale’s opening day. He was accompanied by Yasuda and his wife; Izumi and his wife, Harumi; and the Kawamuras.

Noguchi had met Junichi Kawamura in 1975 when Junichi was a young architect in Kenzo Tange’s office and was involved with the Sogetsu Kaikan project, then in its early stages. Impressed by Noguchi’s brilliance and his deep understanding of architecture, and enchanted by Noguchi as a man as well as an artist, Junichi made him a sort of mentor. “Noguchi’s eyes were beautiful,” he recalls. “He looked young and energetic, although he was seventy. He was energetic in relation to women, too.”4

Junichi wanted Kyoko to meet Noguchi, so in January 1978, after the Sogetsu job was finished, they traveled to Shikoku. When they arrived in Mure, Noguchi led them into the stone circle, where his immense black granite Energy Void dominated the space. Kyoko, a professional koto (Japanese zither) player, had studied Japanese music at Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music, but she knew almost nothing about contemporary art. She was, she says, “shocked and impressed” by the loop of stone. “I had never seen this type of sculpture before. Noguchi told me he thought it was one of his best.” Kyoko’s fresh and untutored response to his work must have pleased Noguchi. He sat in the void of Energy Void and had his picture taken. He and his two young guests so enjoyed their lunch together that the couple stayed on for dinner.

Although Kyoko spoke little English and Noguchi’s Japanese was not fluent, she felt a kinship with him when she discovered his love of music. After dinner, having learned that she was a koto player, Noguchi put on some of the records of indigenous music that he had collected over the years. One of the records was a koto recording by Kyoko’s former teacher. “When I first met Noguchi I felt he was a foreigner, but then his favorite music was the same as mine. He played Indian music and Indonesian gamelan music.” When Noguchi put on African drum music and started to dance, Kyoko and Junichi joined him. He was not, Kyoko recalls, adept at social dancing, but he was good at improvising.

This lively and warm encounter with two such admiring young people must have been welcome. At the time of their visit, Noguchi was still saddened by the suicide of his lover Ayako Wakita, the wife of his former assistant Ajiro Wakita, a young abstract painter. The Wakitas had been living in New York when, unhappy in her marriage and disappointed by Noguchi’s lack of commitment, Ayako left both men, returned to Japan, and hanged herself.

Noguchi and the Kawamuras remained good friends for the next five years. Then, in 1982, Kyoko and Noguchi began a love affair that lasted until his death, six years later. Noguchi was touched when, at the November 1982 opening of his Akari show at Osaka’s Kasahara Gallery, Kyoko presented him with a bouquet of cosmos flowers. Drawn to her warmth, her beauty, and her youth, he invited her to come with him to the opening of an Arshile Gorky exhibition at Tokyo’s Seibu Museum of Art. The following month Noguchi sent Kyoko a plan he had drawn for landscaping the area around his Mure home, together with a note that said, “As you can see there will be a stage where you will play the koto and sing. I can almost hear you!” He sent warm regards to Junichi and closed with “To you I send love.”5

Kyoko began to visit Noguchi’s compound in Mure and she often accompanied him on his travels. In Mure, when she came out to the stone circle to watch Noguchi work, instead of treating her like an unwanted distraction as he was wont to do with other visitors, he would greet her with a gentle smile. By nature a quiet person, Kyoko was happy to observe and not talk. “Izumi told me it was a sacred space,” she recalls. Indeed, at the end of the workday Izumi would have his assistants scatter salt on the stone circle’s ground to purify it. While Noguchi was working, Kyoko would stay in the house playing the koto that Noguchi had given her so that he could enjoy her music. The sound of her playing seemed to give him a measure of calm. “When I stopped playing he would come and say, “‘Why did you stop?’” One of the sculptures that Noguchi was working on in the early 1980s was Kyoko-san, which at five feet two is approximately the height of Kyoko. It is clearly a female form—a curved cut defines buttocks. There is also the hint of a breast, and the sculpture’s spritely movement suggests a kimono-clad woman dancing.

Kyoko-san, 1984. Adesite, ht. 64 in.

In September 1983 Kyoko accompanied Noguchi to the city of Sakata to attend the opening of the Domon Ken Museum. They also visited his beloved Kyoto, where he took her to see all the temples and gardens that had had such an impact on his vision. In summer 1984 in Pietra Santa he spent the day working on marble sculptures assisted by Giorgio Angeli, who invited them to dinner almost every night. In mid-July they went to Forte di Marmi, a beach resort not far from Pietra Santa. Here Kyoko took a photograph of Noguchi wearing a European-style, rather minimal black knit bathing suit that showed off his trim physique. In the photograph Noguchi lounges in a beach chair clearly enjoying the feeling of sun soaking into his body and relishing, too, the adulatory gaze of his young lover. As always, he wears a hat to protect his bald head. After this moment of leisure they toured Italy, visiting Florence, Bologna, and Venice. Then, following a brief stay in New York, Noguchi returned to Mure to work and to be with Kyoko.

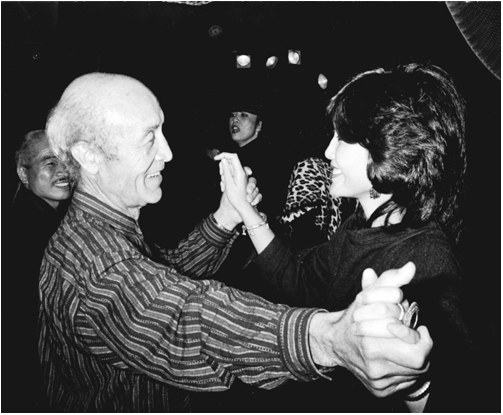

That fall Kyoko and Junichi attended Noguchi’s eightieth birthday party at Sogetsu Kaikan, cohosted by several of Noguchi’s good friends including Kenzo Tange, Hiroshi Teshigahara, Yoshio Taniguchi, and Issey Miyake. Among the guests were many who had furthered Noguchi’s career in Japan. From New York came Shoji Sadao and Priscilla Morgan. Noguchi welcomed the guests and, acting bewildered, said, “Do I have so many friends?” which made everyone laugh.6 It had taken a long time, but Noguchi was surely gratified finally to be loved and honored in his father’s country. His recent stone sculptures, among them Kyoko-san, were displayed in Sogetsu Kaikan’s stone garden that Noguchi had called Heaven. The show received favorable press. The Asahi shinbun said that the works revealed the character of the stone itself as well as expressing the “sheer will power of the still-youthful Noguchi.”7 At an after-party gathering Noguchi took off the elegant jacket that was a gift from Issey Miyake and danced with Kyoko, honoring her by making their relationship public.

Noguchi and Kyoko Kawamura dancing at Noguchi’s eightieth birthday party, Tokyo, 1984

Noguchi’s friends and associates describe Kyoko as petite, unassertive, sweet, and lovely to look at. Maurice Ferré, who visited Kyoto with Noguchi and Kyoko, said: “Noguchi invited a gorgeous Japanese lady to spend that weekend. Kyoko was a wonderful woman—beautiful, expressive, intelligent. She was quiet and did not participate in conversations.”8 Kyoko was emphatically feminine. As apparently behooved a Japanese woman, her behavior was deferential. She was always looking after Noguchi’s comforts, massaging his back when it hurt, giving him affection when he felt down. Most people saw Noguchi and Kyoko’s relationship as more physical than intellectual. In terms of intellect, Priscilla was a more vigorous partner. But Noguchi enjoyed a real intimacy with Kyoko and he trusted her enough to tell her about his childhood. She recalls that there were tears in his eyes when he talked about his mother reading him Greek myths.

Junichi did not appear to mind his wife’s attachment to Noguchi. He and Kyoko seemed to have agreed to give each other a great deal of freedom. In addition, Noguchi was highly supportive of Junichi’s career, often steering work his way. The three of them frequently traveled together. According to Bonnie Rychlak, Noguchi’s assistant at the Noguchi Museum, “It was a ménage à trois.” Noguchi loved the adulation and affection that both spouses gave him. Being with Kyoko assuaged his loneliness and his despair at the acceleration of time’s passage. She made him feel vital, handsome, and successful.

At Noguchi’s eightieth birthday party, the art dealer Ryunosuke Kasahara asked Kyoko to persuade Noguchi to let him mount an exhibition of recent stone sculptures in his Osaka gallery. “When I first met him I thought Noguchi was like a Zen Buddhist monk or priest,” Kasahara recalls.9 Noguchi, however, was difficult: “He was a very strict man with a short temper, but he had a gentle aspect as well. He did not trust people. Unlike Henry Moore, Noguchi was selfish, sometimes very cold, sometimes warm, like fire or ice. On that first visit Noguchi told me in a harsh voice, ‘I do not like gallery owners,’ and I thought, ‘This is a unique and interesting man.’ I had to approach Noguchi many times before his attitude changed. On the fifteenth approach I saw a sculpture called Childhood made of aji stone and I asked to buy it. Noguchi said, ‘It’s expensive.’” Kasahara bought the sculpture, which infuriated Masatoshi Izumi because Noguchi was famous for not wanting to part with his stone sculptures.

On February 9, 1985, Noguchi attended the opening of his Space of Akari and Stone exhibition, designed by Arata Isozaki and installed by Tokyo’s Seibu Museum, after which he and Kyoko traveled to the Barrier Islands off the coast of Indonesia, where they swam and enjoyed the long white sand beach. “He was a good swimmer,” Kyoko recalls. “The waves were very high, and I could not get back to shore. Noguchi swam out and pulled me to shore.” From Indonesia they traveled in March to India, a country that Noguchi loved and wanted Kyoko to know. Part of his reason for going to India had been to give his friend Prime Minister Indira Gandhi advice about how to revive Indian folk art and to promote its export. Although she had been assassinated four months prior to their arrival, Noguchi was welcomed as a guest of the government. The trip to India was not a success. Kyoko recalls that Noguchi came down with a cold and became so ill he had to be hospitalized. Kyoko arranged Japanese meals for him and to comfort him she sang Japanese lullabies. As soon as he was strong enough to travel Noguchi and Kyoko returned to Japan, and from there Noguchi went on to New York.

Around this time Noguchi told Kyoko that he felt he was weakening. He still suffered from back problems. He had had an enlarged prostate (in the 1960s he had a prostate operation). His teeth kept breaking for no apparent reason, and he had had cataract surgery on both eyes. In a diary entry from fall 1986 Kyoko wrote that Noguchi seemed “driven as though he had to hurry because he had no time left.”10 Arata Isozaki noted Noguchi’s being always “on the run … Perhaps it is that Isamu is continually gauging the amount of work he still had to do.”11

In April 1987 in Honolulu his back was so painful that he was hospitalized. Painkillers, shiatsu sessions, and ten days of rest enabled him to walk again. He returned to Japan and began to see an acupuncturist in Otsu, near Kyoto. In New York in the summer of 1987 he was again immobilized with pain. A Japanese acupuncturist gave him some relief and he took up a regimen of physical therapy to strengthen his spine. Late in September he was once again hard at work in his Mure stone circle.

Four days before Christmas 1987 Noguchi and Kyoko flew to Los Angeles on their way to Santa Fe to spend the holiday with Ailes. Wanting to show Kyoko all of his best works while he was still strong enough to travel, he took her to California Scenario.12 In Santa Fe Noguchi and Ailes sat before a fire and shared memories of their mother. On New Year’s Eve in Manhattan, Noguchi, Kyoko, and Junichi went to a party given by I. M. Pei and watched fireworks from his balcony. A day or so later Junichi and Kyoko took Hiroyuki Hattori, the young president of a high-tech firm in the city of Sapporo, Japan, out to Long Island City to talk to Noguchi about a park that they hoped Noguchi would create in Sapporo. As they toured the museum, Noguchi stopped to look at some of the bronze models for his unrealized projects such as Play Mountain and Monument to the Plow. “My best things have never been built,” he observed.13 Even in his last years Noguchi kept hoping to find a place to build Play Mountain and his Memorial to the Dead of Hiroshima.

In March 1988 Noguchi, Kyoko, and Junichi went to Sapporo (on Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido), where Hattori and the mayor guided them around the outskirts of the city to look at possible sites for the future park. First they went to a piece of land where a new university of the arts would be built. They had lunch in a forest, Kyoko recalls, but Noguchi showed his disinterest in this site by asking in the middle of lunch, “Until when do we have to be here?” The place had many trees, Noguchi pointed out, and it did not need to be improved with art. Next they went to the Sapporo Art Park. Noguchi was disgusted: “It’s like a graveyard of sculptures,” he said. Finally they went to Sapporo’s municipal dump, a vast open space at Moerenuma. It was surrounded on three sides by a loop in the Toyohira River, and it had a broad hill where garbage had been piled. Noguchi was immediately taken with it and wanted to turn the whole 400-acre space into one large sculpture—the biggest of his entire career.

Having made a model for the park in Junichi’s Tokyo office, he returned to Sapporo a few weeks later. He went there again in the third week of May, and he made a final trip to Sapporo on October 18. His plan for the park included all kinds of imaginatively designed play equipment, a slide in the shape of Mount Fuji, a glass pyramid inspired by the one I. M. Pei had built at the Louvre, a pyramidal hill tall enough for skiing, a stage, a fountain, a swimming pool, a grassy mound surmounted by an open pyramid made of stainless steel columns, and facilities for various sports. What must have made Noguchi happiest was that he would finally build his Play Mountain, and, at thirty meters high, it would be even bigger than his rejected design from 1933.

Moerenuma Park, Sapporo, Japan, a posthumously completed project

That July Noguchi took Kyoko to Paris for five days. They visited Monet’s home and garden at Giverny. He also took her to the Musée d’Orsay to see his favorite painting, Henri Rousseau’s The Snake Charmer, which she found menacing. From Paris they went to Pietra Santa, after which they stopped in Rome before moving on to Greece in August, where they stayed on the island of Paros in a small hotel near the summer home of Noguchi’s Philadelphia friend, Penny Bach. When Bach took her guests to Paros’s famous marble quarries she was struck by Noguchi’s avidity. “Isamu practically ran into the depth of the quarry. It’s below ground and therefore scary. He wanted to go down into the depth, but I said we should do it another day accompanied by some experienced friends.”14 With the potter Stelios Ghikas they descended the deep shafts of the ancient marble quarries at Marothi, where Noguchi found a translucent chunk of Parian marble that he wanted to take home with him.15 It was too heavy to carry, and in any case Bach told him it was illegal to remove any marble from the quarry. Noguchi was tenacious: he planned to ask the film star Melina Mercouri, who was then cultural minister of Greece, to let him have the rock.

Bach also took Noguchi and Kyoko to her favorite beach at Kolymbithres (meaning “baptismal basins”). To avoid crowds they went early in the morning. “It was primeval,” Bach says. The water was turquoise and the beach with its golden sand was flanked by beautiful stone formations. “We swam and rested on rocks. I was lying fairly nude on a rock and Noguchi took all of these pictures of me.”16 Noguchi was happy: “A person should bathe here before he dies,” he said.

Noguchi told Bach that he wanted to go to Delos, a Cycladic island with extraordinary archaeological sites, and the legendary birthplace of Artemis and Apollo. Bach made arrangements for the trip by boat. “The wind came up the day before,” she recalls. “Noguchi was not feeling well and he said he didn’t want to go. I was surprised: Isamu and I were both experience junkies. I’d never known him not to want to do something.” Before Noguchi and Kyoko left for a speaking engagement in Delphi, he told Bach that her house needed an Akari lamp. “I said, ‘I guess I do.’ He sent me six Akari lamps, one for every room in the house.”

After participating in a conference in Delphi about the state of art (August 19 to 21), Noguchi and Kyoko flew to Japan, where, on August 26, during a long interview with Kazue Kobata (intended as an aid to his future biographer), Noguchi said, “[I’m] trying to figure out how many sculptures I can make.” In late September he was back in Paris for the rededication of his UNESCO garden. He was delighted with how much the trees had grown in thirty years. Time’s passage was clearly on his mind when he told a Japanese journalist: “Nowadays everything in the world has become too ‘instant.’ People are interested only in the newest things in culture, and they chase one thing after another. That is very dangerous.”17 In his last years Noguchi often spoke disparagingly about the state of the world, and especially about the state of the art world, which he saw as overly commercial and obsessed with novelty. “I think a terrible thing is happening to the arts. There is a kind of proliferation, an enormous irresponsibility … I have totally given up the idea of doing sculpture. The idea of doing art as such is sort of ruined by the art business … It is not merely the increase of people but the increase of things, ideas and trends. It is all the fault of advertising, the fault of education, the desire for money and success. All that has been rolling into this enormous garbage heap which is going to flatten us all.”18

In 1988 Noguchi was even more restless than usual. It was a restlessness that could only be assuaged by work—especially by the carving of hard stone that, being timeless, allowed him to venture outside of time. He crisscrossed the world, moving from New York to Miami to Japan to Italy, as well as to many other cities. “I have always been a wanderer. I have never been able to be a practicing artist in the sense of production and a gallery and applause and success.”19 But he was certainly successful. In October he was in New York to accept the Order of the Sacred Treasury at the Japanese consulate. A pendant of gold rays hanging from a ribbon was hung around his neck. A newspaper report quoted Noguchi in a sanguine mood: “I think that the world is in a state of transfiguration and that America and Japan play a leading role … and it is my tremendous good fortune that I find myself at that particular point where I might be of some influence.”20