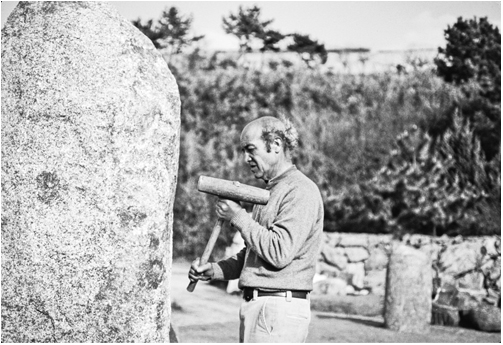

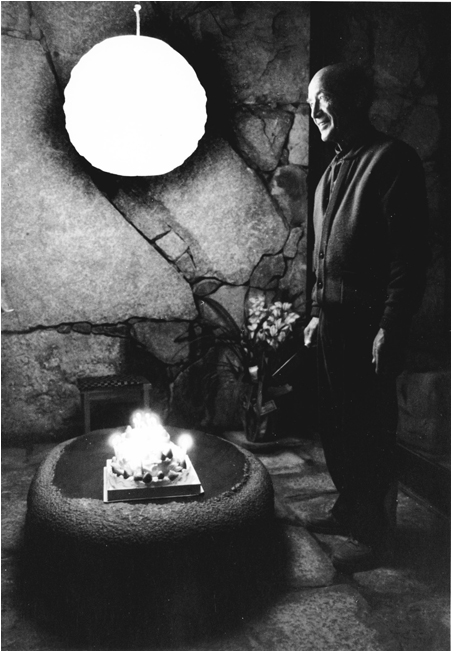

A November 17, 1988, photograph of Noguchi celebrating his eighty-fourth birthday on Shikoku shows a wizened yet vital man holding a carving knife with which he is about to cut two birthday cakes. At the party Noguchi showed his assembled guests his new model for Moerenuma Park, and Issey Miyake showed a video of his fall collection of clothes full of pleats that, like the ribs of Akari, gave life to light. From Miyake and Noguchi’s point of view, the clothes were works of art in themselves. On this birthday Kyoko remembers Noguchi gazing at the autumn-flowering persimmon tree in the garden behind his house and saying, “Will I see the persimmon flower next year?”1

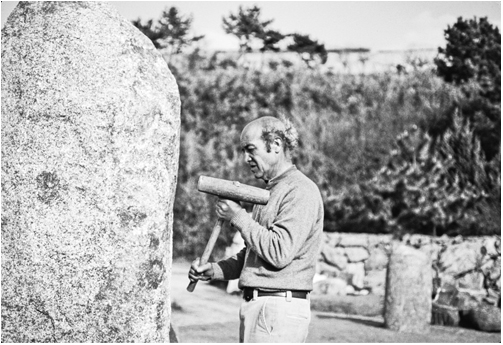

When Kasahara visited Mure in Noguchi’s last years, Noguchi seemed, he said, “to be looking for a way to return to his origin … One evening just before dinner, when he recited his father’s poem ‘The Inland Sea,’ he was about to burst into tears, so he sat down not wanting to show his tears.”2 During the day Kasahara watched Noguchi at work in the stone circle. “He was banging the stone with his chisel, but he was old, so he just put a mark on the stone and asked the stonecutter to work on it. He tried to carve but he was not strong enough.” One evening the cook brought out a seabream that was still alive for Noguchi and Kasahara’s inspection. “This live fish made a sound on the cutting board,” Kasahara recalls. “When Noguchi heard it he exclaimed, ‘Oh, that’s wonderful! That kind of liveliness can come to us after we eat this fish.’”

Two days after his birthday Noguchi and Kyoko traveled to Kyoto to stay at Yamakiku, Noguchi’s favorite ryokan, run by Kinuko Ishihara. His back continued to give him trouble so he went to nearby Otsu to see his acupuncturist. “It seemed to help him,” Ishihara recalls. “In the evenings he asked me to put down only one futon in his room instead of two because he wanted a hard bed for his back.”3 Yamakiku was not an especially luxurious ryokan, but it was very exclusive—guests had to be recommended by other guests, and it only had three rooms. “He treated my ryokan as if it were his house,” says Ishihara. “He felt relaxed and cozy there. Our neighbor had a huge garden and Noguchi loved to sit and look at the garden. The ryokan was near the zoo and Noguchi liked hearing the animals’ cries. When he arrived he’d say, ‘I’m home!’ He would go straight to his room and read a book. He spent a lot of time reading in his room. When he left he’d say, ‘I’m going.’ He’d come on short notice. If the ryokan was full he’d get angry because he assumed that it was like his own house.”

Noguchi’s relationship with Kyoko was romantic, but also convenient and comfortable. She not only looked after him, she also helped to take care of Akari sales in Japan. He sometimes looked after her, too. “One day Isamu told me that he wanted to give me something. I said no, so he paid for his dentist to fix my teeth.” He asked her to marry him but she refused. She already had a husband of whom she was fond. Noguchi asked, “Why don’t you leave him?” With Junichi, Kyoko had an affluent, easygoing, and full life. Moreover, she did not want to separate in part because of the negative feelings about divorce in Japan. She recalls that in his last years Noguchi was contemplating making a more permanent home in Japan. No doubt he would have shared that home with Kyoko and Junichi. “He wanted to be near the sea and he wanted it to be warm. He liked Kyoto, but it was cold in winter. He thought of the Izu peninsula [on the Pacific coast] or Chigasaki.”

Noguchi working in the stone circle, Mure, Shikoku, late 1980s

Soon after his eighty-fourth birthday Noguchi and Kyoko went to Osaka, from where he would fly to New York in time for Thanksgiving. In Osaka they met with the architect Tadao Ando and Ryunosuke Kasahara to discuss Noguchi’s upcoming show of bronze sculptures. Noguchi was not happy with one possible venue for his exhibition, so they went to see a recently completed space, designed by Ando. “It was an annex, a space on top of a building of about ninety-nine square meters,” says Kasahara.4 Noguchi decided this was where he wanted his sculpture to be shown. That evening Noguchi and Kyoko went to a Bunraku (puppet) show, a traditional form of theater that Noguchi had always enjoyed. When the play was over he and Kyoko went backstage to meet the narrator, a well-known performer who was about to retire. Perhaps because of the actor’s age, Noguchi, feeling old himself, was moved by the encounter. The next day Noguchi flew to New York. Kyoko planned to join him on December 17.

Noguchi had Thanksgiving dinner at Priscilla’s apartment. With Shoji and Tsuneko Sadao there, it was very much a family group. From New York Noguchi flew to Italy, where he spent his days in Pietra Santa working single-mindedly on six marble sculptures. He came down with a cold, in spite of which, from early in the morning until night, he kept working outside in the rain.5 When he arrived back in New York on December 12 he took to his bed. He was scheduled to go to a meeting of his foundation’s board of directors the day after he arrived. Priscilla, hearing his hoarse voice, advised him to skip the meeting. She would go and later would fill him in on what was accomplished. When Priscilla arrived at Noguchi’s Sixty-ninth Street apartment, she found him feverish and lacking an appetite. She squeezed fresh orange juice for him. The next night Noguchi was no better, so Priscilla decided to stay at his apartment to look after him as she had done after his various back operations. On December 16 Noguchi’s doctor made a house call, diagnosed pneumonia, and arranged for an ambulance to take Noguchi to New York University Medical Center. Noguchi dressed carefully, so carefully that Priscilla asked him why he wanted to look so elegant if he was only going to the hospital. Noguchi said that she would not understand, meaning that with her patrician appearance she would always be treated with deference, whereas he, a mixed-breed, needed to dress like a gentleman. On their way to the hospital he told Priscilla that he didn’t think that he would leave the hospital alive. Perhaps he was thinking of his mother, who had been hospitalized in mid-December and died of pneumonia two and a half weeks later. Noguchi once told Kitty Roedel that he did not want to die the way his mother had.

Noguchi celebrating his last birthday, Mure, Shikoku, November 1988

According to hospital records Noguchi was admitted on December 17. “He called me from the hospital,” Kyoko recalls. “He asked me to come to New York. I had the key to his apartment. We planned to go to Mexico together—while he was in Pietra Santa he had read a thick guidebook about Mexico to prepare for our trip. He told me he would die if he stayed in that hospital. He wanted to move to another hospital. I wanted to go to New York, but Shoji Sadao said, ‘Don’t come. If you tried to care for him Priscilla would be offended.’”

Over the next few days none of the drugs that the doctors prescribed helped; Noguchi’s condition worsened. Priscilla watched over him and kept all other visitors away, even his sister Ailes, who flew in from Santa Fe. Priscilla thought that if he saw Ailes he would think he was going to die. The one person Priscilla did allow at Noguchi’s bedside was Arne Glimcher. Glimcher gave Noguchi a momentary lift by talking about his next Pace Gallery exhibition. “When I visited, Noguchi had been in intensive care but he was now back in his room. I told him that he looked much better. His doctor and Priscilla thought he was better. But Noguchi said something strange to me. He said that his mother had died in the hospital of pneumonia and he was going to die of pneumonia at the age of eighty-four.”6

Noguchi became more and more withdrawn. When Priscilla read The New York Times to him he was no longer interested. At three in the morning of December 24 he had a heart attack and was moved back into the intensive care unit. An oxygen mask was put over his nose and mouth. Unable to talk, he communicated by writing notes. One of the notes said, “Am I finished with pneumonia? What date?”7 Another almost illegible note, written perhaps around December 27, asked, “Is Sunday New Year Maybe 4th for Kyoko? Ask Jack What is today. When can I eat.” The word “eat” was so shakily written that he wrote it a second time in larger letters. After wearing the oxygen mask for three days, Noguchi tried to take it off. He tried to remove the intravenous needle from his arm as well, so the doctors ordered his hands and feet tied to the bed. At 1:32 in the morning of December 30 Noguchi died, according to the hospital, of heart failure.

* * *

When Kyoko arrived in New York she was not allowed to see Noguchi’s body. She was told that it was already far away. Noguchi was cremated and half of his ashes were placed in a corner of his museum’s garden. The other half was taken to Mure. Thus, even in death he was divided between East and West. His funeral and burial services were private. On February 7 there was an afternoon memorial service at the Noguchi Museum attended by some four hundred people. Kyoko played the koto and sang. There was music by another of Noguchi’s friends, and speeches by Shoji Sadao and Anne d’Harnoncourt, among others. At a gathering at Priscilla’s after the memorial the guests were shocked when Junichi said how proud he was to have shared his wife with Noguchi.

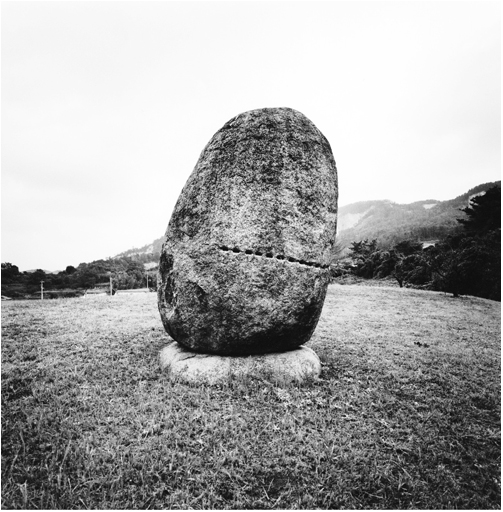

A few months later there were two other memorial services. Following Japanese custom, the one in the Mure stone circle took place one hundred days after Noguchi’s death. After the service, Noguchi’s ashes were carried to the top of his garden and placed inside a large upright oval boulder of pinkish mannari granite, which, years before, Noguchi had found in Okayama and had transported to Mure. Admiring the boulder after it was installed in the stone circle, he had asked Izumi, “Would it be okay for me to be inside this stone?”8 Izumi told Noguchi that it was too early for him to die. In 1985 Noguchi drew a line with red bengara around the stone’s girth. “By the time Noguchi died the line had faded away,” says Izumi, “but we could just see where it was and we cut the stone in half and I carved out a hollow for his ashes.” The ashes were placed in the cavity, and the two halves of the egg-shaped rock were put back together. Poised on a mound at the hill’s summit, the rock has a wide view of nearby mountains and, in the distance, the Inland Sea, whose islands had given Noguchi such a wealth of stone and inspiration.

Noguchi’s grave on top of the hill garden behind his house at Mure, Shikoku

A week after the Mure memorial the Segerstroms arranged a memorial at California Scenario. There was a koto player dressed in a kimono, and a traditional tea ceremony performed by a woman from the Orange County chapter of a tea ceremony school. One hundred and fifty people were offered bowls of bitter green tea and a brunch of fruit, sushi, frittata, and sweets. Shoji Sadao spoke of the relationship between the Eastern and Western ceremonies: “There’s a kind of symmetry to it and almost a mystical thing about it,” he said. Toren Segerstrom spoke of Noguchi as a brilliant artist who believed in the power of gardens. “To say you love someone sometimes is not enough. To say ‘Thank you’ to someone for showing you a different way of looking at the world is sometimes not enough. To create a new garden, no matter how big or small, is to say, ‘Thank you, Isamu Noguchi.’”9

Noguchi was mourned by friends, coworkers, and lovers. Even though he was cool, secretive, and very much a loner, people who knew him were saddened. Priscilla devoted her life to his legacy, working hard to make the Noguchi Museum the wondrous place it is. When she spoke about Noguchi there was a passion in her voice that made it clear he was alive in her thoughts. Just as she was once the perfect artist’s wife, she was now the artist’s dedicated widow. Shoji Sadao has worked hard to finish projects that were not completed before Noguchi’s death. He oversaw, for example, the completion of Time and Space, a monumental sculpture at the Takamatsu airport, which, like Noguchi’s homage to the lima bean at California Scenario, looks like a cluster of elephantine boulders. The most important unfinished project that Sadao shepherded to completion was Moerenuma Park, which opened in July 2005. Kyoko Kawamura treasures Noguchi’s memory and speaks wistfully about his death. Although her marriage seems happy and stable and her career flourishes, with regard to Noguchi she still seems bereft.

The art world bemoaned the loss of Noguchi as the grand old man of twentieth-century sculpture. His obituaries were full of accolades. Allen Wardwell, then the director of the Noguchi Museum, told the press: “America has lost its greatest living sculptor. Of course he was much more than a sculptor—he was a designer of spaces, stage sets, gardens, fountains and the decorative arts. He was a great thinker and visionary.”10 Martin Friedman called Noguchi “a paramount and essential figure in the evolution of 20th-century sculpture.”11 Anne d’Harnoncourt said, “He never lost his extraordinary youthful sense of invention and enthusiasm. The creation of his museum spaces in Long Island City was an extraordinary gesture, beautifully carried out. He did it with great grace … He was a wonderful free spirit.”12 Art historian Albert Elsen, who has written so authoritatively about modern sculpture, wrote in Art Journal that Noguchi’s Dodge Fountain in Detroit was “one of the greatest fountains ever designed.”13 In The New Yorker Calvin Tomkins called Noguchi “the most significant public artist of his time.”14 The sculptor Joel Shapiro posed the question: “There is David Smith and Noguchi and who else in this country?”15 Tadao Ando wrote that Noguchi was “the last master since Henry Moore … Words cannot describe my anguish at his passing.”16

Ninety-four-year-old Martha Graham had seen Noguchi not long before he died. When she learned of his death, she said: “So much of my life has been bound artistically with Isamu Noguchi. I feel the world has lost an artist who, like a shaman, has translated myths of all our lives into living memory. The works he created for my ballets brought to me a new vision, a new world of space and the utilization of space. Isamu, as I do, always looked forward and not to the past.”17

* * *

Noguchi looked both ways. For him time flowed both forward and backward. He longed to return to origins. “I wanted to see the horizon again as in the beginning of things.”18 But time’s passage never stopped bothering him. “I still don’t seem to have come to terms with time,” Noguchi said in 1964.19 In his autobiography he wrote: “And if I sometimes built pieces that appeared to have some abiding worth, they, too, were like spirit money, signs to ward off the disaster of time.”20 His anxiety about life’s brevity drove his creative process, as did his unease with the pull of East and West. He needed to encompass time within his sculpture, either by concretizing it in stone or by making gardens in which the ambulatory viewer moved through time. He wanted to transcend time by creating something beautiful and enduring, but he also wanted to go with time’s flow, allowing his work to change over the years and to return to the earth, which, as he so often said, we all must. To challenge time and to acquiesce to time, stone was his chosen weapon. “Stone breathes with nature’s time cycle. It doesn’t resist entropy, but is within it. It begins before you and continues through you and goes on. Working with stone is not resisting time, but touching it.”21 In his mind his stone sculptures were just temporary incursions into a process of change that would go on forever: “All I do is provide an invasion of a different time element into the time of nature.”22

Walking in his museum’s garden with Dore Ashton, Noguchi once mused: “I have come to no conclusions, no beginnings, no endings.”23 He maintained this open-ended stance, partly because he was so full of wonder. “I’m still making discoveries, I’m still finding new ground. That is to say, once ground is found, there’s any amount of it left to find. You go from one place to another, but the earth is round and infinite. It’s a continuous discovery.”24 “Awareness” was a word that Noguchi used often. When asked if there was anything for which he wanted to be remembered, he answered: “If I could have contributed something to an awareness of living, and awareness of this changing and this continuity.”25 Sometimes when he spoke of awareness, he waxed mystical and otherworldly. Art, he said, comes “from the awakening person. Awakening is what you might call the spiritual. It is a linkage to something flowing very rapidly through the air. I can put my finger on it and plug in.”26 Another time he said: “The whole world is art … If one is really awake, he will see that the whole world is a symphony.”27 He called sculpture a process of “opening awareness … Art is quite invisible and weightless; it hovers over the surface. Appearing anywhere, oblivious of time, we know it when we hear it, see it, clear as recognition.”28 Speaking of this awakened state with Martin Friedman, Noguchi said: “If you allow yourself to be—or imagine yourself to be—part of all phenomena, then you are able to be anywhere, and the artist is merely the shaman who is able to contact all these other phenomena. Therefore, you are really free and you really don’t belong anywhere.”29 In the mid-1980s he set forth his concept of awareness in The Awakening, a tall basalt sculpture that stands motionless but alert, its smooth skin marked by just a few cuts of the chisel. With its silence and mystery this stone awakening is indeed shamanlike. It listens.

To the end of his life Noguchi kept talking about not belonging. In 1988 he told a Japanese interviewer: “You might say, in some way, that I’m an expatriate wherever I am, either in America or in [Japan]; that I’m, after all, half-breed there or half-breed here.”30 Julien Levy noted that Noguchi as an outsider became extra vigilant, “landing always like a cat on his feet.”31 For Noguchi his sense of homelessness was an impetus: “My longing for affiliation has been the source of my creativity.”32 Noguchi, the nomad, sought and found, by making sculpture, a way to embed himself in the earth, in nature, in the world. “We are,” he said, “a landscape of all we know.”33