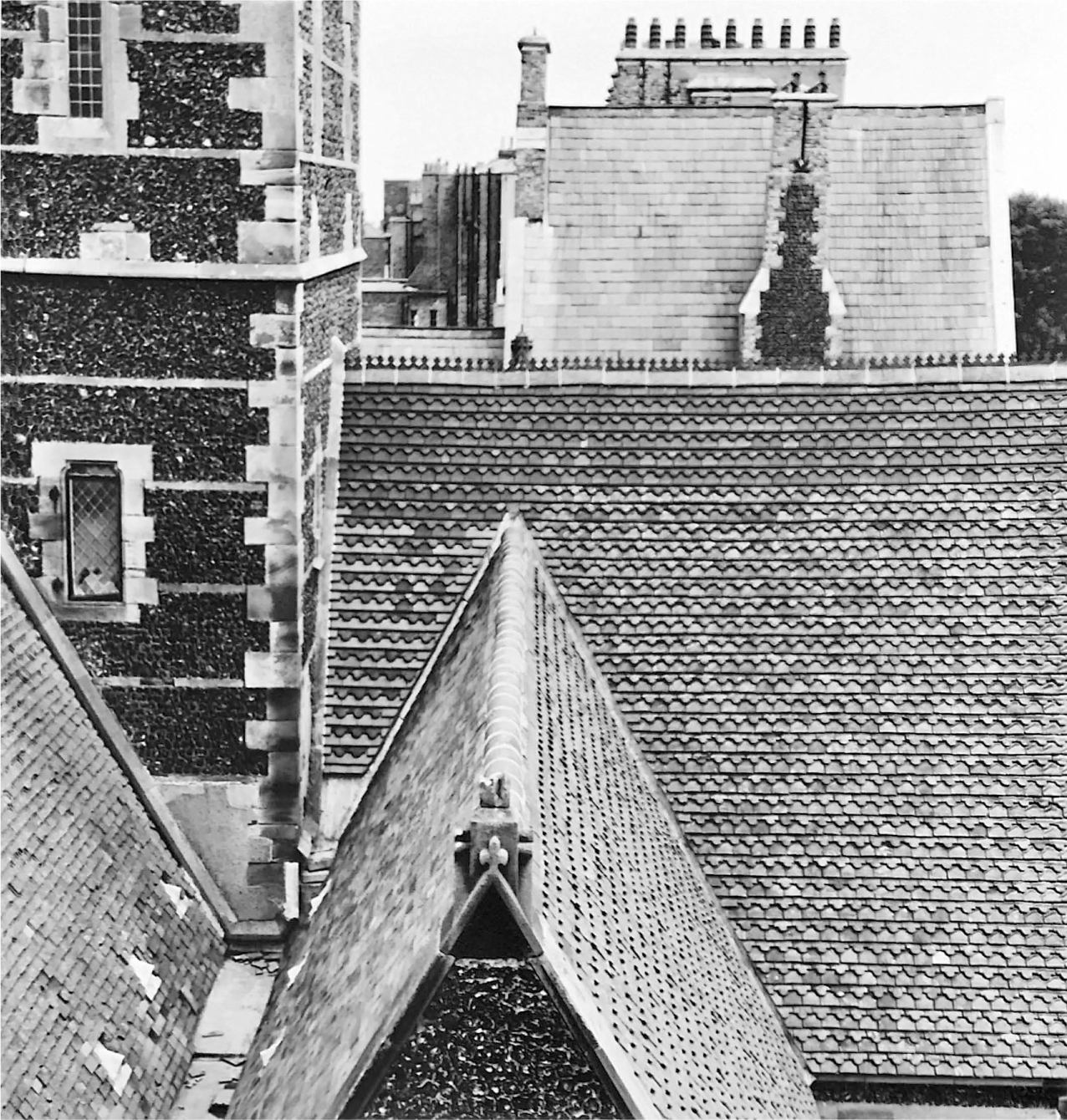

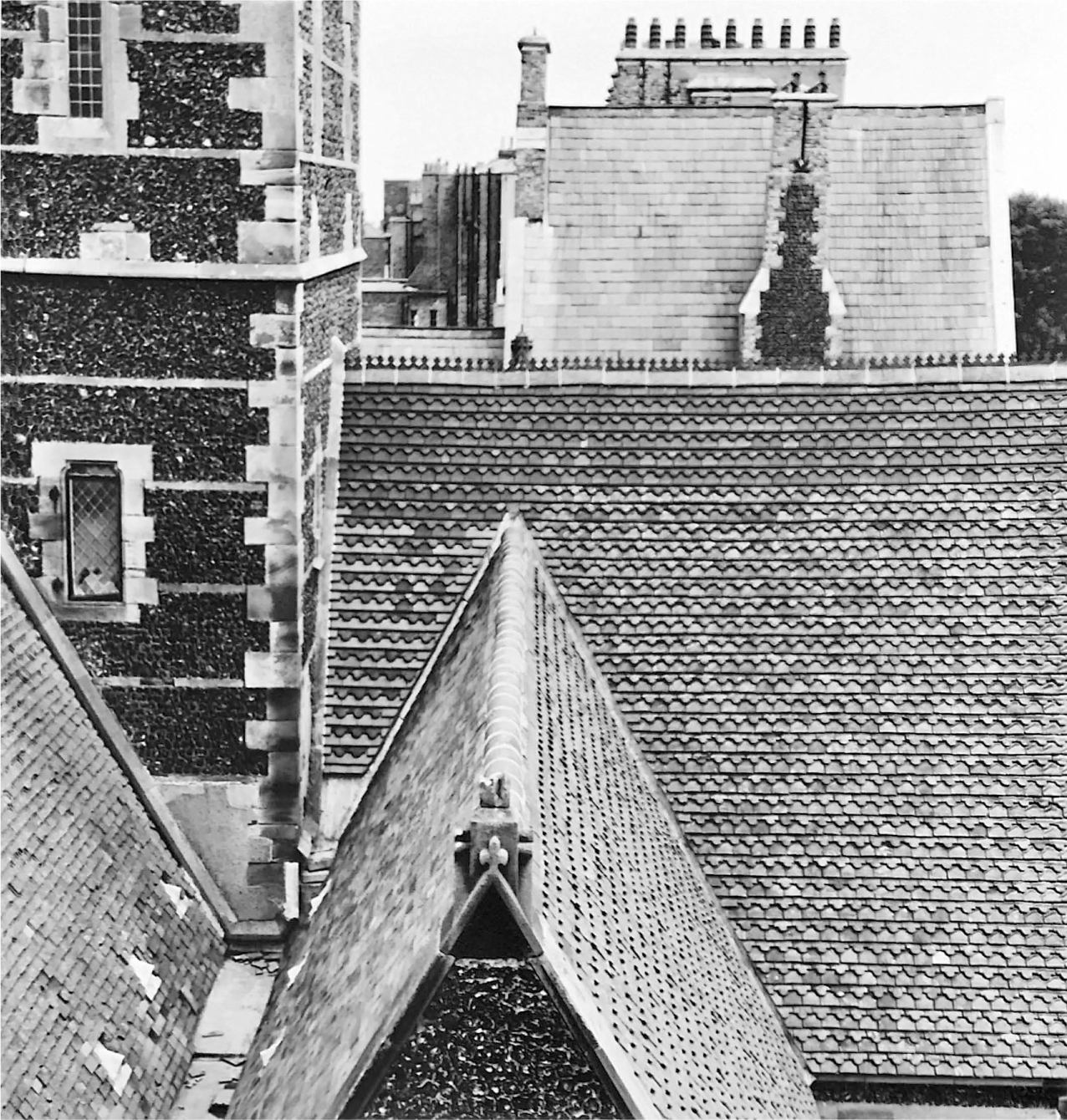

Augustus Pugin, The Grange, Ramsgate, 1843.

Father and Son

Robert Clark

When I was living in London St. Pancras station was always in view. You could see its spires and towers from the doorstep of my flat and pretty much from anywhere in Finsbury and Bloomsbury. I thought it was magnificent—the greatest Victorian building of all—but as with my affection for much Victoriana, I was a bit sheepish about it. I never quite knew if it was truly magnificent or simply too much. John Summerson, one of the essential architecture critics of the twentieth century, split the difference and called it “Sir George Gilbert Scott’s tawdry masterpiece.” He also admitted to finding the building “nauseating” and I think I know what he meant: that there was something queasy making in looking at it; on the one hand, the sense that in its height, its ascending piles of ornament, and ceremonial, even liturgical style, it’s worthy of awe; on the other, that one’s being suckered by its scale and pretensions into admiring what is ultimately in bad taste, not magnificent but vulgar. It is, after all, not a cathedral or a seat of government, but a train station with a luxe hotel stuck on front. Scott had been commissioned to build the new Foreign Office in Whitehall, but the government refused to countenance his Gothic Revival design. It’s said that he recast his ideas for that project in St. Pancras, built in 1868, employing them there with some bitterness, perhaps with the sense that the station was indeed a lesser, tawdrier piece of work.

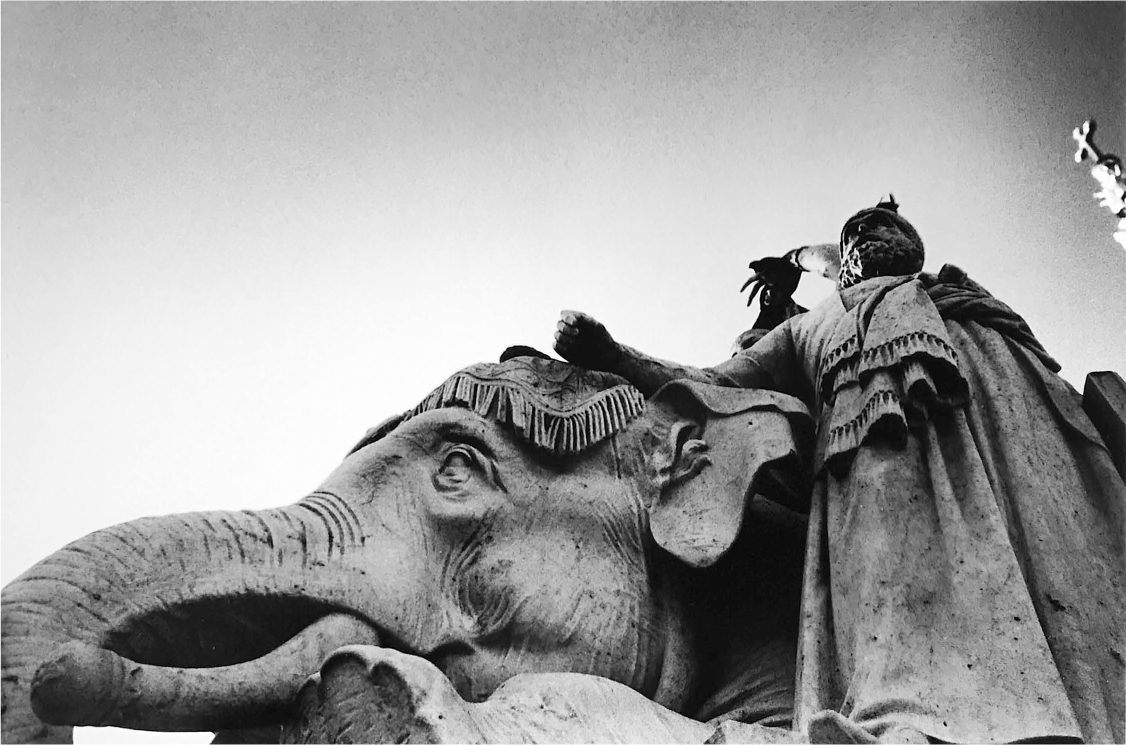

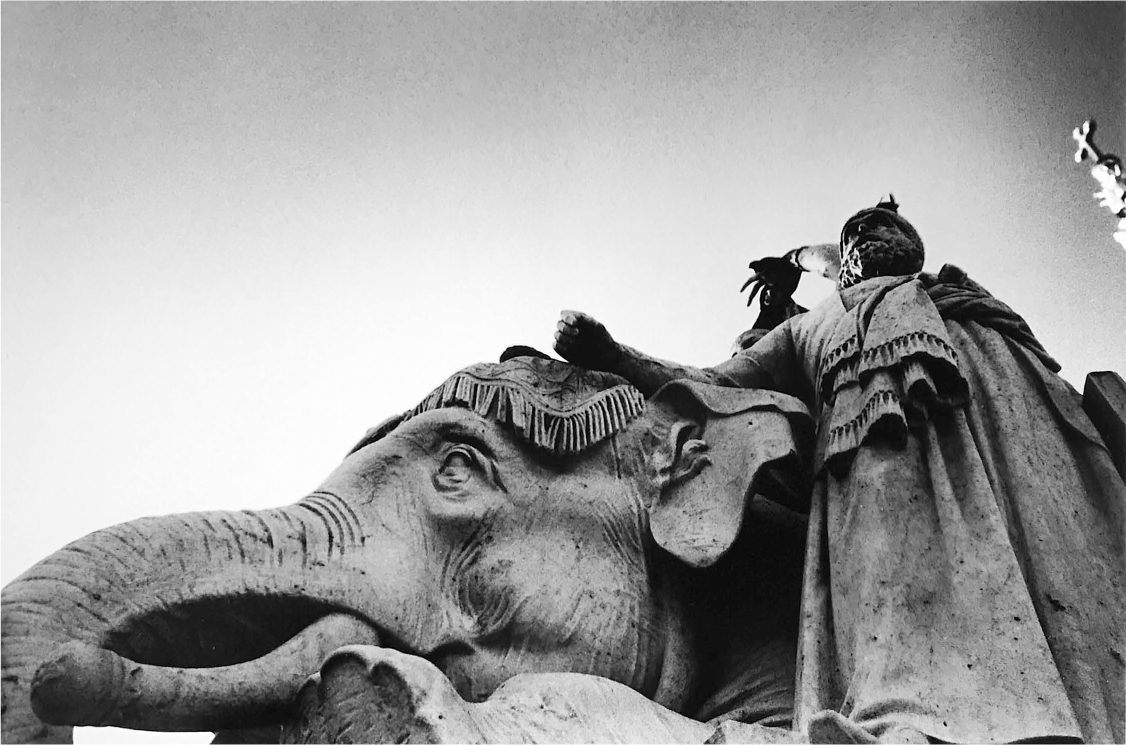

That couldn’t be said of the dozens of churches and cathedrals Scott built nor of the Albert Memorial, which perhaps even more than St. Pancras was the most Victorian piece of all Victoriana. It confounded me: was it monumental or overbearing, stunning or elephantine (and there are elephants, in tribute to Britain’s colonial possession of India), an expression of national grief or of bloated sentiment? It could have been any or all of those for me; what it was for the Victorians themselves I can’t say and I wonder if they could; if their mixed feelings about faith, progress, family and gender relations, and paternal authority were summed up in this manifestation of confusion; the jumble of ornament and motifs, an art fully convinced only of its desire to ascend and make a weighty impression on the earth, but toward what? I went to photograph it once but only shot close-ups of the elephants: the thing in toto was too much; it would have been preposterous were it not also somehow diffident, a monument not just to loss but, it seemed to me, a sort of failure, an imperial gesture touched by perplexity.

Scott finished up the most prominent and doubtless richest architect of the Victorian age and launched a dynasty via his son George Junior, and grandson Giles Gilbert, who designed Liverpool Cathedral, the Thames powerhouse that now houses the Tate Modern, and, not least, the ubiquitous red telephone kiosk found throughout the nation. But it was George Junior who interested me most, the one whom architectural historians said was the most gifted of the three, who most deeply plumbed the possibilities of the Gothic Revival and foreshadowed those of modernism. Unlike his father, he didn’t produce many finished buildings and only a handful of those still stand. He was an intellectual magpie and a wayward Catholic convert. He died alcoholic, broke, and insane, estranged from his children just as he had been from his own father, in a bedroom in the St. Pancras Hotel. He was, perhaps you would say, my cup of tea. I’d read everything (which was not very much) about him and went to photograph his places.

George Gilbert Scott Sr., Albert Memorial (detail), London, 1864–76.

George Junior is supposed to have built seven or eight churches and chapels, a larger number of houses and rectories, and some college buildings. He went to work in his father’s practice after attending Eton, supervising some of the firm’s projects and church restorations. Working on one of these at Cambridge, he was inspired to enroll as a student, earning a “first” and then a fellowship at Jesus College after winning a prize for an essay, “The Intellectual Character of the First Cause, as affected by Recent Investigations of Physical Science,” which aimed to defend the idea of divine origin of creation against Darwinism.

Unlike many Victorian sons—especially of successful fathers—Scott wasn’t a rebel or antiauthoritarian, at least not in a conventional sense. His politics were Tory and became more conservative over time and, as the essay showed, his Christian belief remained intact. It was, in fact, the deepening and intensifying of his faith—ending in Roman Catholicism—that would make him a black sheep. It also informed his architecture, which rejected the High Victorian style of his father and his generation for a more austere late medieval English Perpendicular Gothic he felt was better suited to worship as conducted by High Anglicans and Catholics. But it was precisely the churches that embodied that approach most successfully that were gone, damaged by bombing in World War II, considered beyond repair and pulled down. That wouldn’t stop me from photographing them, or rather the places they’d stood. I was beginning to like photographing such absences, or at least not feeling frustrated or overly disappointed by them. It seemed to allow me to make a special claim upon them: to be seeing what other people couldn’t, to be peering into a world that belonged solely to me.

Just then, I went on a date with an art historian, a specialist in Victorian photography, and after we’d had coffee at the Tate Britain—communing with some daguerreotypes and a couple of whopping Turners—we agreed to meet up at a Scott church in Camberwell in south London. I think she was just as keen as me; it was she who’d known about the church and had always wanted to see it.

We meant to meet on a Sunday but it was raining hard. I told her not to bother coming, that we’d do it another time. But I went by myself and I cannot say why. I checked the timetables and saw that the closest train station was Denmark Hill, close by the site of the house John Ruskin, the art and architecture critic, grew up in. It was a place I should photograph.

I knew the house was gone, that it had been razed and most of the grounds turned into a public park. But I wasn’t prepared for how absolutely it had been erased, the site now a street of turn-of-the-century suburban villas on a faceless road with only a car wash and a filling station standing out against the rain and the gray. I found a tiny marker indicating where it had once been and stood next to it, sopping, my camera sheltered under my coat, staring down a driveway bordered by shrubs, a big Mercedes parked at the end.

I never got to the church, which, it turned out, wasn’t by George Junior at all but by his father. My date’s source had been wrong. As ever, where Junior’s work wasn’t obliterated it was misattributed and, still more, overshadowed by his father’s—eight hundred buildings against Junior’s dozen or so—his father’s houses and edifices of every description that constitute an outline of Victorian society, which made up the stages and scenery of the Victorian novels I loved and my nineteenth-century obsessions: his churches, of course—143 either designed or rebuilt—to hold all that faith and unfaith; forty workhouses for the likes of Charles Dickens’s father and everyone else who failed to have money; Reading Gaol for sexual and gender misfits like Oscar Wilde; and four lunatic asylums to hold, among others, his son, George Junior.

Of course, the site of the Ruskin house too hadn’t really been Ruskin’s place but his father’s. There are always fathers—even (maybe especially) in their deepest absences—but to me nowhere so strikingly as in the Victorian age with its beards and seers and Old Testament thunderers and “driving” amassers of wealth, overseen by a small but formidable woman who adored her husband, Albert, like a daddy’s girl does her daddy, who had him memorialized on an uncanny, perhaps absurd scale by George Junior’s father.

A few days later, I went to Ramsgate on the English Channel and there too George Junior had been slighted, this time in converse fashion with a building of his own mistakenly attributed to his father. It was a chapel in the municipal cemetery on the fringe of an ugly neighborhood. The cemetery had a long drive that led straight down to the chapel, which was shaped like a squared cross with a tower at the center. The tower, though, was taller on one side than the other, topped on the left by a smaller secondary tower. To the right of this was a window, off-center. It seemed to me that this arrangement should throw the balance of the whole structure off. So should the fact that the windows on the wings on each side of the base of the tower were also out of kilter and of different shapes and proportions. It ought to have seemed lopsided and clumsy and hodgepodge, but it didn’t. It was a rebellious building, flouting the rules of Victorian Gothic, his father’s architecture, and getting away with it for reasons I couldn’t put my finger on. I tried to go in but the door was locked. I photographed a piece of exterior wall, a downspout, and the trees behind the building. Their limbs ran all in one direction, away from the sea, contorted by a perennial wind that wasn’t blowing that day.

The other reason I’d come to Ramsgate was to visit The Grange, the home of the architect Augustus Pugin, though it was less a house than a compound, around which Pugin had grouped a church, cottages, and a full-fledged monastery, a village within the larger town. Pugin was the main founder of the Victorian Gothic Revival and George Gilbert Scott’s chief inspiration: “the thunder of Pugin’s dreams” had been his creative epiphany, Scott said. For Pugin, Gothic was more than a style; it was a complete manifestation of England, of English culture, of medieval communitarianism built around social cohesion, obligation, labor and craft, and charity, with the church at its core. Pugin was a brilliant architect and designer—he’d been the cobuilder of the Houses of Parliament—but, still more, he was an aesthete and a passionate Catholic convert, a man in constant pursuit of beauty and the divine. As an acquaintance wrote, “He rushed into the arms of a church which, pompous by its ceremonies, was attractive to his imaginative mind.”

I went overboard at The Grange. I photographed inside and out, in black-and-white and color: hallways, roofscapes, fireplaces, a bed and its coverlet in the master suite, a flagon and an empty holy water stoup by the door of Pugin’s private chapel. I shot until I ran out of film, until I was sated. As with other Victorian buildings that had drawn me in, even obsessed me, after a while I felt overwhelmed, swamped in detail, in crockets and pointed arches and saturated polychrome and gilded decorations. I was submerged and the water was pouring in; an attic full of accreted gorgeousness, a jumble of marvelous doodads and bric-a-brac was closing over my head. Walking back to the station, I knew that I now had seen a place I’d sought for a long time, that it had been beautiful, and that, oddly, dully, I had no desire to ever return.

Pugin’s counterpart inside the church was undoubtedly John Henry Newman, the famous High Church Anglican priest whose conversion to Roman Catholicism and elevation to a cardinalship stunned the Victorian world. Medievalism and the Gothic were the artistic and cultural expression of the “Oxford Movement” (in which Newman had been the leading figure) that returned the English church to its pre-Reformation roots and cultural centrality. In fact, much of the opposition to the Gothic Revival was based less on aesthetic considerations than the fear that it was a stalking horse for Roman Catholicism, as was the case with the rejection of Scott’s first design for the Foreign Office. Privately, Pugin would doubtless have admitted this.

Victorian faith was under threat from two opposing sides: Darwin and the phenomenon labeled by Thomas Henry Huxley “agnosticism” on one and, on the other, defections to the Roman church by prominent figures like Newman, rationalism and neo-medieval piety that jointly pressed upon a national Anglican Church increasingly incapable of inspiring even the most rudimentary faith. For every expression of religious doubt or renunciation by people like George Eliot, Ruskin, and Virginia Woolf’s father, Leslie Stephen, there seemed to be a conversion to Catholicism by a prominent Victorian academic, writer, or clergyman, sometimes at the hands of Newman himself, who had received the likes of Gerard Manley Hopkins, among others.

Another would be George Gilbert Scott Junior. His father had been a devout architectural follower of Pugin but had never felt the need to follow him into the Roman Church or even High Church Anglicanism. It was George Junior—a rebel against Pugin’s strictures on late medieval style—who “went over,” though reading his biography, I began to feel that his conversion was less spiritual than temperamental, that Junior’s general pessimism arose from and in turn fed a sense of failure, of lassitude, and creative stasis, a sort of disassociation: “Old work was real … ours is not real, but only like real,” said one of his contemporaries, Norman Shaw. But as with his political conservatism, Catholicism did seem real, insisted on its own eighteen-hundred-year-old tradition as both authoritative and unalterable. And without it his creative work could only be empty: “a blank skepticism, or an arbitrary agnosticism, have never, and never can, originate any advance either in art or in any other department of practical life.”

In 1880, George Junior was introduced to Newman and shortly thereafter attended a morning mass celebrated by Newman on his behalf. Afterward he

had not walked fifty yards down the street before as it were a momentary flash of thought passed through my mind and I saw in an instant that all the difficulties, uncertainties and indecision of years was but a phantom, and that my duty was clear as day. I experienced even then no emotion, no surprise, I was not only cool but even cold. Simply all my old difficulties fast tumbled down, in a moment, like—so to speak—a house of cards, and I had quickly made up my mind to become a Catholic before I reached the second street corner.

George Junior’s family was appalled, relieved only that he had waited until after his father’s death two years earlier. Beyond the social embarrassment that came with his conversion, there was its impact on the family architectural firm (now managed by his brother), dependent as it was in large part on commissions from the Anglican Church.

To George Junior himself, his conversion seemed utterly rational, even practical, but in the eyes of others it was a manifestation of mental instability and those closest to him had reason to think this. His drinking—“alcoholic drink is … the properly & divinely designed beverage of man,” he’d said—was resulting in unexplained absences, night wanderings that sometimes ended in the company of prostitutes or in arrest. In 1881, he had his first bout of mania and within another year he was committed to the Royal Bethlem Hospital—Bedlam—afflicted with paranoid delusions. On release, he was arrested several more times while carrying a knife for protection against his imaginary persecutors. His family applied to have him permanently committed, but he fled to France before the judge could issue a ruling.

George Junior had long stretches of lucidity during his exile: “I am in a rather droll position … hav[ing] been declared legally a lunatic, incapable of managing my affairs in England, while here in France I have been examined by the official medicals, and have been pronounced with equal certainty to be perfectly sane.” But returning home there were more arrests and hospitalizations. In January 1888 he was committed to Saint Andrew’s Hospital for Mental Diseases at Northampton for the Middle and Upper Classes. There his room overlooked the hospital’s chapel, designed by his father.

He made several attempts to escape and was eventually released, only to relapse into his customary bouts of drinking, mania, paranoia, and run-ins with the law. He worked sporadically, mostly on his final project, the Catholic cathedral in Norwich, which his brother finished when George Junior became incompetent again. In sum, he had produced thirteen buildings in his career against his father’s eight hundred.

After 1894 there are few records or evidence of his whereabouts. But by 1897 he was inhabiting his final quarters, a room in the St. Pancras Hotel, his father’s masterpiece. He died there, according to the death certificate, of “acute cirrhosis of the liver and heart disease” and of “exhaustion syncope,” heatstroke and dehydration. His sons, who would only recall having met him once before, were brought to his bedside. Whether he received last rites from a priest isn’t known or still less what he might have made of dying there, of all places. He was poor by then—he’d been cut off from the family fortune, his father’s fortune, long before—and I suppose it was a cheap room near the attics, among the castellated chimneys and crocketed pinnacles and spires.

My own conversion—now twenty years ago—was remarkably like George Junior’s, less felt than arrived at as a necessary, logical, and inevitable destination. It was a kind of intellectual assent—enthusiastic to be sure—but I don’t recollect much sense of freedom or peace, of mercy having befallen me and sins being wiped away, of loving God and of him loving me. What I liked was the beauty not only of the content—the music, liturgy, architecture, and art—but of the form, the organic, self-containing tradition and belief that seemed to go back as far as I might see. That too seems much like George Junior, the comfort of a self-sustaining and self-evident order, a stay against meaninglessness.

It’s easy to connect all that to fathers, or, in my case and the case of so many Victorians, the absence of a father, or a father whose presence was felt by way of money or reputation or a shame in not being equal to his measure and it’s on that account that he’s gone. So you might replace a father with God the Father, with an institution that’s gently authoritarian, that corrects and instructs without anger or injustice. You might feel safe there, maybe for the first time ever.

But it’s also not much of a leap to connect the role of father in Victorian times not only to conversion but to the lapse and loss of faith, and to a broad and deep sense of loss, of failure, of reality having been emptied out. God the Father disappears or perhaps is in some unwitting way killed, an obstacle moved out of the way by the son, as in the myth of Oedipus, as Freud—another Victorian—would assert. God left us, abandoned us, but that, in truth, was our desire; God had to die and we had to kill him. His simultaneous love and oppression, his tender but iron hand, was too much to bear. In that view, to wish to have him back afterward would be, in the inexorable flow of history, a fool’s errand, for all the efforts of a Scott or someone like me.

As I said, my conversion was twenty years ago and not long after I made a trip to England. I located the village where my ancestors had come from. It was called Somerton and what I found was a crossroads of twenty or so houses, thickets, and meadows, and, in the meadows, sheep. There was a church too, and although there was no one around—no one in the whole village apparently—it was being kept up: the grass in the graveyard was freshly cut and I supposed I had ancestors buried here, though there were no monuments or stones with their names. Not being of much social standing—fleeing to America to try to improve their lot—there probably never were.

The church—St. Margaret’s by name—is at least a thousand years old, though there’s no saying when my family turned up there. The oldest parts of the church date from the 1100s and there’s a blockedup doorway in the Romanesque style that preceded the Gothic. The baptismal font is nearly as old.

I suppose that given how much of my conversion was based on aesthetics—on chant, on beautiful hints of hidden mysteries—I was a convert of the same sort as Pugin or George Junior: I’d become as much a neo-medievalist as a Catholic; what they’d said about Pugin’s conversion—that it was “attractive to his imaginative mind”—was exactly true of me too. I thought about Somerton while I was in Ramsgate; although Pugin’s compound was altogether magnificent and stately and St. Margaret’s was altogether humble, they both manifested what Catholics called the sacramental, outward signs of inward, invisible, spiritual things, intimations of God, of ultimate beauty and truth. But I was afraid I couldn’t see them anymore, that my religion was or had become abstract, academic, maybe sentimental, a kind of nostalgia for feelings I’d never, in fact, felt. That, maybe, was where my interest in the Victorian era had come from, when the decisive battle of faith versus doubt was fought by people who could express themselves only in architecture and novels and sensed from the start it was going to be a failed enterprise. Maybe I was looking for a way to be a believer who was also a doubter, instruction from a father/mentor who could show me how to do it and then leave me to go my own way, maybe to prosper, maybe to become a more contented failure at both faith and art.

One day every man turns around and sees that for all the struggles he’s made to live with being a son, he’s become a father or at least an old man despite himself. George Junior’s sons came to him as he lay dying in his own father’s building, his house, so to speak. His life was concluded—he couldn’t, as a son can, regard it as a work in progress that might be turned around or amended or justified—and now there would be a reckoning, a toting up of what must be regretted since it was too late to atone for. His sons stood at his bedside and there was nothing he could be in their presence but a father entombed in the encrustations and brick his own father had built at the height of his powers. Did he say he was sorry, and if he had, what would that have amounted to?

Of course, George Junior had already converted and presumably was still a believer on his deathbed. But he was unconscious when his sons reached him and they wouldn’t have the satisfaction of seeing him confess his sins as he took his last breath and perhaps feel their own resentments and wounds ease, if only a bit. Maybe they forgave him anyway, shamed him with their mercy, or—who can say?—allowed him to die at peace with himself. If nothing else, two of them became architects, and good ones too.

George Gilbert Scott Sr., Midland Grand Hotel and St. Pancras station, London, 1866–78.

I took the train to the Northampton General Lunatic Asylum on a squally Sunday afternoon to take pictures. The name is now simply St. Andrew’s Hospital although it is still a psychiatric facility. I’d done a little more reading about it before going and learned that Virginia Woolf’s cousin James Stephen had been a patient contemporaneously with George Scott Jr., committed for the same manic depression she was afflicted with, which ran in her family, and in those of Turner and Ruskin and so many other Victorians.

The grounds were beautiful, a classical terrace of wards overlooking a vast lawn. When I arrived, there were a dozen or so people playing croquet—inmates, I supposed. At the lawn’s far edge I saw the chapel George Junior’s father designed. It would be visible from any of the wards and so Junior could have seen it whenever he looked out. I wondered what that was like for him: this manifestation of his father’s incessant productivity and mastery of the conventions of Victorian Gothic that George Junior hadn’t fully succeeded in overturning. Or maybe it made no impression because his experience was by then entirely internal, a knot of paranoid fantasy. People were trying to poison him, assassins had been hired; he had more pressing things to worry about than the insults and accusations of his father’s chapel.

Or maybe—and this is how I believed it must have been—he’d have looked out and the chapel would have stared back, shaming him. Alcoholics are habituated to shame as are sons of eminent men (and maybe all sons to some extent). There were trees around the chapel, big conifers that cast pools and rivulets of light flowing in the direction of the wards. Gazing out, George Junior would have seen them approaching, serpentine, mirroring what he’d conjured up in his own brain.

He had no choice about being committed to St. Andrews, but in his next and final home he embraced the same dialectic—son and father, art and shame—even more profoundly, taking a room inside the St. Pancras Hotel, deep within his father’s oeuvre, swallowed up by it until what proved to be the very end.

The photos of St. Andrews came out underexposed; that shifting light played tricks on my meter, or that is how I excused myself from the failure; that’s what I would have told anyone who might take me to task me for it. And now I am thinking of an extract from the diary of General Charles George Gordon, the hero of the Fall of Khartoum, another failure the Victorians had turned into a triumph by means of sentimentality and grief, written as the Sudanese enemy was beginning its siege, the things that were on Gordon’s mind as he was preparing to die. He quoted the Bible: “The eye that mocketh at his father and despiseth to obey his mother, the ravens of the valley shall pick it out, and the young eagles shall eat it.” And then he added, “I often wonder whether they are destined to pick my eyes, for I fear I was not the best of sons.”

One of the crucial things that separated the children of Victorians from their parents’ generation was their indifference to the opinion and regard of their fathers; in Bloomsbury and other outposts of the modern movement, they made, in fact, a virtue of rejecting most of what their fathers thought most important. They (and perhaps we, or at least I) didn’t much care about or for what their forebears did—or built. It seemed to them self-evident that those fathers’ posterity culminated in nothing so much as the slaughter of the 1914–18 war. They, the Victorians, had been in deadly earnest, held to deadly sureties that sent their sons and grandsons to the trenches, flung buttresses and pointed arches backward in time toward what they would have liked to be true, toward buildings that “were real,” as George Junior’s colleague wrote, knowing that “ours is not real, but only like real.” The ravens would come regardless, whether anyone deserved it or not.