President Truman’s approval rating sank to 22 percent by February 1952. The war remained an unresolved nightmare, mired in petty haggling at P’anmunjŏm and punctuated by fierce battles over a landscape that resembled the horrors of World War I trench warfare. Many thought Korea was a conflict that was neither noble nor necessary. Edith Rosengrant of Springfield, Colorado, a widowed mother of six children, wrote a stinging letter to Truman, enclosing her son’s posthumously awarded Purple Heart: “Soldiers need help when they are fighting … Dick’s life was thrown away by his own country’s cowardly leaders.”1 Halsey McGovern of Washington, D.C., lost two sons in Korea, Lt. Robert McGovern, who won the Medal of Honor, and Lt. Jerome McGovern, who won the Silver Star. They died within eleven days of each other in early 1951. Mr. McGovern took an even more dramatic and unprecedented action than Mrs. Rosengrant to express his bitterness. He notified the Pentagon that he would not accept the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for valor, or the Silver Star on behalf of his sons because the president was “unworthy” to “confer them on my boys or any other boys.”2

Donna Cooper of Memphis, Tennessee, also returned the Purple Heart awarded to her fallen son, Pvt. Paul Cooper, who was killed in October 1951. She wrote:

Dear Mr. President:

Today I buried my first-born son. Having known the depth of his soul, I can find no place among his memories for the Purple Heart or the scroll. I am returning it to you with this thought: To me, he is a symbol of the 109,000 men who have been sacrificed in this needless slaughter, a so-called police action that has not and could never have been satisfactorily explained to patriotic Americans who love their country and the ideals it stands for. None of us appreciate the degradation and ridicule we have to suffer because of a pseudo war. If there had been a need for armed conflict to preserve the American way of life, I could have given him proudly and would have treasured the medal. However, since there was nothing superficial in his whole life, I cannot mar his memory by keeping a medal and stereotyped words that hold no meaning and fail to promise a better tomorrow for the ones he died for.3

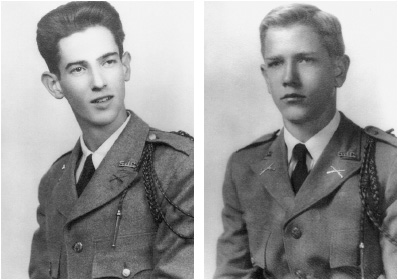

Robert McGovern and Francis McGovern as students at St. Johns College High School in Washington, D.C. Robert McGovern was a member of Company A, 5th Cavalry Regiment, First Cavalry Division. He was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions near Kamyangjan-ni on January 30, 1951. Eleven days later, his brother, Francis McGovern, posthumously earned the Silver Star for his actions near Kŭmwang-ni while serving with Company I, 9th Infantry Regiment, Second Infantry Division. (COURTESY OF CHARLES MCGOVERN)

Recrimination and disillusionment over Korea, rabid McCarthyism, and personal attacks against Truman and Acheson brought with them a thirst for profound political change. Eisenhower’s declaration of his candidacy for president in 1952 led many to express optimism that his experience in foreign policy and moderate position on domestic issues made him just the right person to replace Truman.

Polls showed that the war was the foremost issue on the American people’s minds, and the election would largely become a referendum on Korea. Eisenhower addressed the issue directly on October 24, when, in a blistering speech, he promised to forgo “the diversions of politics” and concentrate on the task of closing the war that “has been the burial ground for 20,000 American dead.” Korea, he said, “has been a sign, a warning sign, of the way the Administration has conducted our world affairs” and “a measure, a damning measure, of the quality of leadership we have been given.” If elected, Eisenhower declared dramatically, “I shall go to Korea.” The speech drew high praise and rave reviews from the press. The New York Times hailed the speech and endorsed Eisenhower. For Emmet Hughes, Eisenhower’s speech writer, “psychologically, this declaration (“I will go to Korea”) probably marked the end of the campaign. Politically, it was later credited … with sealing the election itself.”4 Truman, however, thought using the tragic Korean situation for political gains was contemptible. “Ike was well informed on all aspects of the Korean War and the delicacy of the armistice negotiations,” recalled the chairman of the JCS, General Omar Bradley. “He knew very well that he could achieve nothing by going to Korea.”5 Still, the speech was a masterful political stroke, for it put the Democrats on the defensive, and Eisenhower’s promise to go to Korea, while not offering a specific policy proposal to end the war, nevertheless offered a chance at something new.

Eisenhower won in a landslide against Adlai Stevenson. Keeping his campaign promise, the president-elect announced that he would go to Korea on November 29. He was not yet sure how he would end the war, but he did possess one significant advantage. Republican critics such as Senators Robert Taft and William Knowland would be silent, at least for the time being, and this gave the incoming administration much greater freedom to maneuver.

As soon as news of Eisenhower’s planned trip reached Seoul, President Syngman Rhee announced that he would be given a rousing reception, including a mass rally, parades, and dinners. Rhee saw the visit as an opportunity to convince the new president to resume the offensive to achieve Korean unification. Rhee thought Eisenhower would be sympathetic to the cause of “total victory” both as a military man and as a Republican. “I expect General Eisenhower to bring peace and unity to Korea,” the South Korean president told the New York Times. “We are depending on him.”6 The JCS instructed General Clark to tell Rhee that there would be no public receptions or appearances for Eisenhower because it was too dangerous. The visit would be brief, and Eisenhower’s advisors cautioned him to avoid Rhee. “President Syngman Rhee is old and feeble,” warned John Foster Dulles, Eisenhower’s choice for secretary of state, before his trip. “His will is still powerful and he has three obsessions: (1) To continue power; (2) to unite all of Korea under his leadership; (3) to give vent to his life-long hatred of the Japanese.” Dulles recommended “that political matters be discussed as little as possible with Rhee.”7

Korean civilians during a rally held in anticipation of President-elect Eisenhower’s forthcoming visit to Seoul, November 25, 1952. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

Eisenhower’s time in Korea consisted almost entirely of touring the front and visiting units. He saw his son John, who was serving in the Third Infantry Division. When Eisenhower declined to attend a welcoming ceremony in Seoul, Rhee refused to take no for an answer. On December 4, Rhee went to downtown Seoul where a large “U.S. President-Elect Eisenhower Welcome Rally” at the Capitol Building had been organized. A huge crowd bearing American flags and “Welcome Ike” banners had gathered to see and greet Eisenhower that afternoon. General Paek Sŏn-yŏp recalled the disappointment: “Rhee sat on the stand and waited for the Americans to change their minds and for Eisenhower to show up. I accompanied President Rhee and shook from the cold, as some one hundred thousand Seoul residents waited in bitter weather, sitting on the plaza in front of the Capitol. We waited for Eisenhower, but he never came.”8 Realizing that Eisenhower would not show up, Rhee went to the presidential residence to wait for the president-elect’s courtesy call. Paek was furious. “Whatever the Americans’ real reasons [for not meeting Rhee],” Paek later reflected, “this communication dealt a severe blow to the prestige of a sovereign head of state.” Paek immediately got in touch with General Clark, telling him that in no uncertain terms he could not imagine a “greater affront” to South Korea. “If the president-elect does not visit President Rhee,” Paek threatened, “you will insult President Rhee, of course, but you will also offend the Korean people. If a meeting between the two men does not materialize, any and all future cooperation between the ROK Army and the United States will be jeopardized.” Taken back by the vehemence of Paek’s response, Clark immediately got on the phone with his staff. A meeting was arranged.9

On December 5, the day the president-elect was due to depart, Eisenhower finally met with the South Korean president and his cabinet. The meeting lasted just forty minutes, and nothing substantive was discussed. Rhee nevertheless made sure that the meeting was recorded for posterity. General Clark recalled that the “newspaper people were there, including still and movie photographers. Rhee was certain he was going to have a fine record of the Eisenhower visit.”10 The old patriot needed to save face, but he was angry and confused. He had thought Eisenhower had a grand strategy to drive the communists out of Korea. Eisenhower made it clear, however, that he would not seek unification but rather a truce in Korea, and pursued an alternative strategy to end the war: “My conclusion, as I left Korea, was that we could not stand forever on a static front and continue to accept casualties without any visible result. Small attacks on small hills would not end the war.”11

On December 5, as Eisenhower was flying from Seoul to Guam, MacArthur delivered a speech to the National Association of Manufacturers at the Waldolf Astoria Hotel in New York City, where he announced that he had come up with a solution on how to end the war in Korea. Eisenhower was informed of MacArthur’s proposal, and a meeting between the two men was quickly arranged. Despite mutual antipathy (MacArthur once dismissed Eisenhower as a “mere clerk, nothing more”), Eisenhower was curious to know what the old general had to say. They met in New York City on December 17. MacArthur handed him a copy of his “Memorandum for Ending the Korean War.” The plan called for a two-party conference between the president and Stalin to “explore the world situation as a corollary to ending the Korean War” and to agree that “Germany and Korea be permitted to reunite under forms of government to be popularly determined upon.” If Stalin refused such a meeting, the president should inform him that it was the intention of the United States “to clear North Korea of enemy forces … through the atomic bombing of enemy military concentrations in North Korea and sowing the fields with suitable radioactive materials … to close major lines of enemy supply and communication leading south from the Yalu.” The president should also threaten to “neutralize Red China’s capability to wage modern war.” The memo, MacArthur explained, presented “in the broadest terms a general concept and outline.” He would also “be glad to elaborate as minutely as desired.”12

Eisenhower listened patiently and said, “General, this is something new. I’ll have to look at the understanding between ourselves and our Allies in the prosecution of this war.” Privately, Eisenhower was appalled. “He didn’t have any formal peace program at all,” Eisenhower later confided. “What he was talking about was the tactical methods by which the war could be ended.”13 But the nuclear question remained a central question when Eisenhower deliberated on how best to end the war. Sharp disagreements over how atomic weapons might be used became the focus of intense debate. The air force and the navy believed that atomic bombs might constitute sufficient pressure to force China to accept reasonable armistice terms. The army strongly disagreed. Army Chief of Staff Joe Collins noted that the Chinese and North Koreans were dug in underground across the front and provided poor targets for atomic weapons. Bradley was concerned that casualties in a new offensive would be so great that “we may find that we will be forced to use every type of weapon that we have.”14

There was also concern about the impact of the use of nuclear weapons on the UN coalition in Korea. Between February and May 1953, the National Security Council conducted a series of meetings that were far more “discursive than decisive” in an effort to find a way to end the war.15 Notwithstanding interservice differences, the threat of Soviet retaliation, and the “disinclination” of allies to go along with a military proposal that included nuclear weapons, Eisenhower wanted to take a more “positive action against the enemy” and concluded that “the plan selected by the Joint Chiefs of Staff was most likely to achieve the objective we sought.” The JCS plan included the option of employing atomic weapons “on a sufficiently large scale to insure success.” Secretary of State Dulles, then on a trip to India, told Prime Minister Nehru that “if the armistice negotiations collapsed, the United States would probably make a stronger rather than a lesser military exertion, and that this might well extend the area of conflict.” He also told Nehru that “only crazy people could think that the United States wanted to prolong the struggle, which had already cost us about 150,000 casualties.”16 Dulles’s intent was for Nehru to pass the message to the Chinese that the United States was prepared to use nuclear weapons if an armistice agreement was not soon forthcoming. But Nehru apparently passed no such message to the Chinese and later denied having any role in conveying Washington’s atomic warning.17

Whether Nehru’s denial is to be believed or not, the Chinese were aware that Eisenhower was considering the nuclear option. The new American ambassador to the Soviet Union, Charles Bohlen, was instructed to “emphasize” to the Soviet foreign minister the “extreme importance and seriousness of the latest UNC proposals” by pointing out “the lengths to which the UNC has gone to bridge [the] existing gap” and “making it clear these represent the limit to which we can go.” Furthermore, Bohlen was to point out that “rejection [of] these proposals and consequent failure [to] reach agreement in the armistice” would create a situation that Washington is “seeking earnestly to avoid.”18

Most Americans and others around the world at the time believed that the threat of nuclear war coerced the communists to reach an armistice agreement. “We told them we could not hold it to a limited war any longer if the communists welched on a treaty of truce,” Eisenhower told his assistant, Sherman Adams. “They didn’t want a full scale war or an atomic attack. That kept them under some control.”19 But had nuclear coercion really worked in Korea? Was the threat of nuclear warfare the most important factor in forcing the communists to reach an armistice agreement?20 The answer is, probably not. First, Chinese leaders were well aware of the potential of an American nuclear attack. Indian Ambassador K. M. Panikkar recalled that when Truman raised the possibility that atomic weapons might be used in Korea in late November 1950, “the Chinese seemed totally unmoved by this threat.” General Nie Rongzhen told Panikkar early in the war that “the Americans can bomb us, they can destroy our industries, but they cannot defeat us on land. We have calculated all that. They may even drop atom bombs on us. What then? After all, China lived on farms.”21 The Eisenhower administration’s alleged threat of nuclear war was also issued nearly two months after the communists had already made a significant compromise at P’anmunjŏm. An unexpected breakthrough occurred in March 1953 when the communists suddenly became conciliatory. On March 30, Zhou Enlai declared that the communists would agree to voluntary repatriation.22 Whatever happened to change the communists’ minds between October 1952, when the armistice talks were suspended, and March 1953, it could not have been the nuclear threats made in May. The forces of peace were already in motion in Korea before any alleged threat of nuclear war was made.23

What, then, had happened to change the communists’ mind? Why had they finally come around on the POW voluntary repatriation issue after two years of fruitless talks? If not “atomic brinkmanship,” what suddenly pushed them to the path toward peace?

On March 4, 1953, the Soviet people awoke to the radio bulletin that Stalin was gravely ill. He had suffered from a “sudden brain hemorrhage” with loss of consciousness and speech.24 The world soon learned that Stalin was dead. Power was assumed by a coalition of four men: Georgi Malenkov was appointed premier. Lavrenti Beria retained his position as minister of the interior, while V. M. Molotov, who had known Stalin longer than anyone else, became foreign minister. Nikita S. Khrushchev became Central Committee secretary. There was other startling news. Sweeping changes in the government and party hierarchies were announced.

In the months before his death, Stalin appeared intent on keeping the flames of the war burning bright. In August and September 1952, Stalin and Zhou met to discuss the war’s course. Zhou wanted a settlement in Korea, but he approached the matter with Stalin cautiously, seemingly to agree with Stalin’s hard-line stance while attempting to explore the possibility of a negotiated settlement. Zhou noted that “the [North] Koreans were suffering greatly” and were anxious to bring the war to a close. Stalin responded caustically that “the [North] Koreans have lost nothing except for casualties.” The Americans, he said, “will understand this war is not advantageous and they will have to end it.” He claimed that the “Americans are not capable of waging a large-scale war at all,” because “all of their strength lies in air power and the atomic bomb.” Stalin advised that “one must be firm when dealing with America”; patience was required to beat them. “The Americans cannot defeat little Korea,” Stalin mockingly declared. “The Germans conquered France in 20 days. It’s already been two years and the USA has still not subdued little Korea. What kind of strength is that?” Belittling America’s alleged weakness was probably galling to Zhou since it was the Chinese, not the Russians, who were fighting and dying in Korea. Zhou stated that if the United States “makes some sort of compromises, even if they are small, then they should accept” them, but only “under the condition that the question of the remaining POWs will be resolved under mediation by some neutral country, like India, or the remaining POWs transferred to this neutral country, until the question is resolved.”25 Zhou was trying to find a way to end the impasse over the POW issue. But Stalin continued to discourage the Chinese premier’s desire for flexibility. He reiterated his hard-line stance to Mao in late December.26

General Clark anticipated communist rejection of the proposal made on February 22, 1953, for the exchange of sick and wounded POWs: “There was dead silence for over a month,” he recalled.27 Three weeks after Stalin’s death, the silence was broken. The communists not only agreed to exchange the sick and wounded but also proposed a resumption of the talks, which had been suspended for nearly six months. The communists had abruptly changed their tune and became conciliatory. Stalin’s death was a turning point in the war, although few had been prepared for it.

Many had believed that post-Stalinist Russia would experience a great upheaval. “Some in the West predicted that the Soviet Union would surely undergo a bloodbath,” recalled Ambassador Bohlen. But the predictions proved wrong. Within days of Stalin’s death, it appeared that the so-called guardians of unity—Malenkov, Beria, Molotov, and Khrushchev—were firmly in charge.28 They ushered in a striking shift in foreign policy. Malenkov announced a “peace initiative” in mid-March, stating that “there is no litigious or unresolved question which could not be settled by peaceful means on the basis of the mutual agreement of the countries concerned … including the United States of America.”29 A few days later, Radio Moscow admitted, for the first time since the end of World War II, that the United States and Great Britain had played a role in the defeat of the Axis Powers. Stalin’s “Hate America Campaign” of 1952 was abruptly suspended.30 During Stalin’s final days, Moscow had been festooned with anti-American propaganda: “Placards portraying spiderlike characters in America military uniform … stared down at us from every fence throughout the city,” George Kennan observed.31 These disappeared. The Russians also agreed “to intervene to obtain the release of nine British diplomats and missionaries held captive in Korea since the outbreak of the Korean War.” The changes were not confined to Korea. The Soviet government withdrew Stalin’s 1945 claim to the Turkish provinces of Kan and Ardahan and control of the Dardanelles. After weeks of refusal, Moscow agreed to the appointment of Dag Hammarskjöld as the new secretary general of the United Nations. Moscow also proposed the possibility of a meeting between Malenkov and Eisenhower to discuss “disarmament and atomic energy control.” On June 8, Molotov told the Yugoslav chargé d’affaires that Moscow wanted to send an ambassador to Belgrade, “the first move toward repairing the rupture with Tito.”32

It was all breathtaking, but the biggest change was Moscow’s desire to end the Korean War. On March 19, the Soviet Council of Ministers adopted a resolution that was a complete review of Soviet policy in Korea. In “tortuously convoluted language” that reflected the Kremlin’s unease at fundamentally altering Stalin’s Korea policy, the resolution declared,

The Soviet Government has thoroughly reviewed the question of the war in Korea under present conditions and with regard to the entire course of events of the preceding period. As a result of this, the Soviet Government has reached the conclusion that it would be incorrect to continue the line on this question which has been followed until now, without making those alterations in that line which correspond to the present political situation and which ensue from the deepest interests of our peoples, the peoples of the USSR, China, and Korea who are interested in a firm peace throughout the world and have always sought an acceptable path toward the soonest possible conclusion of the war in Korea.33

The resolution outlined “statements that should be made by Kim Il Sung, Peng Dehuai, the government of the PRC, and the Soviet delegation at the UN” to quickly achieve an armistice.34 Two weeks later, the communists responded positively to Clark’s proposal for exchanging sick and wounded prisoners while also announcing their intention to obtain a “smooth settlement of the entire question of prisoners of war.”35

Despite the breakthrough, Clark was suspicious: “I could not help but think, as I read the proposal to resume armistice talks, that perhaps it was the anesthetic before the operation.”36 The feeling was widely shared in Washington and London. Dulles, in particular, was highly suspicious of the new Soviet leadership and their “peace offensive.” British Foreign Secretary Eden also shared the skepticism, arguing that what changes there seemed to be in Russian policy might be “tactical” moves to dupe the West. Eden, like Dulles, believed that the Soviet Union merely wanted to be more accommodating to gain time to consolidate the new leadership. The Kremlin, according to Dulles, was trying to “buy off a powerful enemy and gain a respite.” Moreover, he argued, it would be an “illusion of peace” if there was “a settlement [in Korea] based on the status quo.” The United States needed to make “clear to the captive people that we do not accept their captivity as a permanent fact of history.”37

Despite Dulles’s reservations, Eisenhower wanted to take advantage of the moment and responded with his own peace offensive in a speech on April 16. He called it “The Chance for Peace.” Eisenhower said he welcomed the recent Soviet statement, but he could accept them as sincere only if the words were backed by concrete deeds. He called for a Soviet signature on the Austrian treaty, an agreement for a free and united Germany, and the full independence of the Eastern European nations. He also called for the conclusion of an “honorable armistice” in Korea. “This means the immediate cessation of hostilities and the prompt initiation of political discussions leading to the holding of free elections in Korea.” In exchange, Eisenhower said, he was prepared to conclude an arms-limitations agreement and to accept international control of atomic energy to “insure the prohibition of atomic weapons.”38 There was no reference to Taiwan or China. It was an expression of the American vision of the conditions of peace in Europe and Asia. The persuasive power of the speech was essentially reactive, not proactive. For critics of the Eisenhower administration, the speech was more political posturing than an actual compromise effort to achieve détente with the Soviet Union.39

Still, the speech was well received. Sherman Adams called it “the most effective of Eisenhower’s public career and certainly one of the highlights of his presidency.”40 Walter Lippmann commended the president for “seizing the initiative” and for beginning discussion and negotiations of the greatest complexity and consequence.”41 But nothing significant was achieved because of it. Moreover, incredibly, it was during this time that the Eisenhower administration began contemplating the use of nuclear weapons to achieve a quick end to the Korean War. Ambassador Bohlen in Moscow believed the United States had missed an important opportunity to fundamentally change its relationship with the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death: “I wrote Dulles that the events could not be dismissed as simply another peace campaign designed solely or even primarily to bemuse and divide the West.”42 Three years of fighting an angry and frustrating war in Korea had embittered Americans against the Soviet Union, and thus it was probably no surprise that Bohlen’s observations fell on deaf ears in Washington. The temporary thaw between the Americans and the Soviets after Stalin’s death did not bring about measurable changes in their relationship, but it did make possible the exchange of sick and wounded prisoners in Korea. In mid-April an agreement was reached at P’anmunjŏm, and Operation Little Switch repatriated seven hundred UNC POWs and seven thousand communist POWs between April 20 and May 3. Only one item remained for resolution for an armistice: the selection of neutral nations to serve as custodians of the prisoners refusing repatriation. But this issue was relatively minor compared to previous hurdles. “Despite these annoyances,” recalled General Clark, “progress toward an armistice appeared to be rapid. None of the disagreements that still existed appeared to be too difficult to overcome.”43

The talks at last reached the point of settlement in early June. The final issue of selecting neutral nations to supervise voluntary non-repatriates was settled when the communist side agreed to establish a Neutral Nations Repatriations Commission with five members—Poland, Czechoslovakia, Switzerland, Sweden, and India. These countries would share in the task of maintaining custody of the non-repatriates in their original places of detention. India would be in physical custody of the non-repatriates. Communist and UN authorities would question the non-repatriates for final verification that their decision was made voluntarily and free of coercion.44 As the negotiators began working out the last details, Clark reported that “the resolution of the POW issue will now make the signing of the armistice agreement possible in the near future and possibly as early as June 18.”45

After nearly two years of negotiations, peace was finally in sight. But one final obstacle remained: Rhee refused to get on board. “An armistice without national unification was a death sentence without protest,” he declared.46 After meeting Rhee just before the POW terms were agreed on, Clark reported that “he had never seen him [Rhee] more distracted, wrought up and emotional.” Rhee had always held out hope that the armistice negotiations would fail. Clark later wrote, “My relations with South Korea’s venerable, patriotic and wily chief of state had been excellent right up to the moment the United States indicated clearly it intended to go through with an armistice that might leave his country divided. Then I became a whipping boy for his bitterness and frustration.”47 Proclaiming the right of self-determination, Rhee insisted that peace must be restored by the Koreans themselves: “We reassert our determination to risk our lives to fight on to a decisive end in case the United Nations accepts a truce and stops fighting. This is imperative because the presence of Chinese Communist troops in Korea is tantamount to denying us our free existence.”48

Washington had assumed that Rhee’s threat to continue fighting alone was a bluff and that he would sign the armistice, and so the administration was caught off-guard by the emotional intensity of his opposition and the scale of popular support from the South Korean people. Clark suggested a mutual security treaty to placate Rhee and the South Koreans. Eisenhower agreed and wrote to Rhee that while he empathized with the South Korean leader’s “struggle for unification,” the time had nevertheless come “to pursue this goal by political and other methods.” The enemy “proposed an armistice which involves a clear abandonment of the fruits of aggression,” and since the cease-fire line would follow the front lines, “the armistice would leave the Republic of Korea in undisputed possession of substantially the territory which the Republic administered prior to the aggression, indeed, this territory will be somewhat enlarged.” He also agreed to negotiate “a security pact … which would cover the territory now or hereafter brought peacefully under the administration of the ROK” in addition to providing “substantial reconstruction aid to South Korea.” He concluded, “Even the thought of a separation [between the United States and the ROK] at this critical hour would be a tragedy. We must remain united.”49 On June 18, Eisenhower received Rhee’s reply. Rhee surreptitiously ordered the ROK Army to release twenty-seven thousand anticommunist North Korean prisoners held in its custody. Clark remembered that “all hell broke loose, at Rhee’s order.”50

The release of the prisoners had been carefully planned. The idea had originated with Rhee himself. Former prime minister Chŏng Il-kwŏn, a senior army commander at the time, recalled that the “release was planned in top secret between retired Maj. Gen. Wŏn Yŏng-dŏk [as provost marshal general in charge of the Korean guard force] and Rhee,” and that he himself had been kept in the dark.51 Only at the last minute was the plan disseminated to key subordinates. At 2:30 a.m. on June 18, Wŏn’s men abetted the prisoners’ escape by “cutting the barbed wire and killing the camp lights.” Meanwhile, the Americans, under orders to fire only in self-defense, tried to turn back the mass of prisoners with tear gas, “but the gas proved useless.”52 When news of the escape was made public, Rhee immediately acknowledged his role in the plan.53

Eisenhower was aghast at Rhee’s perfidy: “What Syngman Rhee had done was to sabotage the very basis of the arguments that we had been presenting to the Chinese and North Koreans for all these many months. In agreeing that prisoners should not be repatriated against their will, the communists had made a major concession. The processing of the prisoners was observed by representatives of both sides. This condition was negated in a single stroke by Rhee’s release of the North Koreans.” Eisenhower immediately sent a warning to Rhee: “Persistence in your present course of action will make impractical for the UN Command to continue to operate jointly with you under the condition which would result there from. Unless you are prepared immediately and unequivocally to accept the authority of the UN Command to conduct present hostilities and to bring them to a close, it will be necessary to effect another arrangement.”54 But what other arrangements could there be? The South Koreans could not possibly win the war against China by themselves and yet they constituted the bulk of the UN fighting force. Rhee could order ROK forces to withdraw from the UNC. This possibility deeply worried the Americans and other UN participants. Rhee could sabotage not only the armistice but also the fate of the UNC, the credibility of the UN itself, and the idea of international collective security. Prime Minster Nehru laid out these concerns in a memo to the president of the UN General Assembly: “In view of [Rhee’s] action, armistice terms become unrealistic and the United Nations has been put in a most embarrassing position which will undoubtedly affect their credit and capacity for future action.” Furthermore, “Chinese and North Koreans can, with reason, object to signing any armistice terms which have not been and are not likely to be carried out.” As a result, “the position of United Nations Command in Korea becomes completely anomalous and the question arises whether United Nations Policy must be subordinated to President Rhee’s policy.” Nehru suggested that the matter be taken up at once by the UN General Assembly since “the whole future of the United Nations is jeopardized.”55

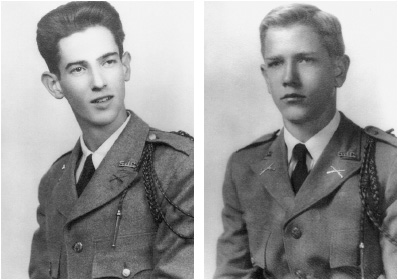

Anti-armistice demonstrations, April 1953. (AP PHOTOS)

The South Korean people overwhelmingly supported Rhee’s actions. On June 25, the third anniversary of the start of the war, Rhee appeared before a cheering crowd and vowed to unify the nation and “fight communism to the death.” With “tears in his eyes,” his voice “broken as the loudspeaker carried his words to the crowds and all over the nation through Seoul radio,” he declared, “What we want, because we know we will die if we follow our Allies, is to be given the opportunity to fight by ourselves. We simply ask to be allowed to decide our fate by ourselves.” The crowd roared and hysterically waved banners that said, “Don’t sell out Korea” and “Down with the Armistice.”56 Daily anti-armistice demonstrations in Seoul and other cities and increasing bitterness threatened to sever U.S.-ROK relations. An alarmed Dulles wrote to Rhee,

Dear Mr. President:

I speak to you as a friend of your nation. As you know I have long worked for a free and united Korea. In 1947 and again in 1948 in the United Nations, I initiated for the United States steps which led to the establishment of your government and international acceptance of the proposition that Korea ought to be free and united … I pledged our nation’s continuing support of that goal. Also, because aggression was an ever-present threat and because your people felt alone, I asserted that free world unity was a reality, and I concluded: “you are not alone.” You will never be alone so long as you continue to play worthily your part in the great design of human freedom.

That pledge of unity was hailed throughout South Korea. It was quickly put to the test, for within six days, the aggressor struck, within a few hours, the brave army of the Republic of Korea was overwhelmed by superior forces and the territory of the Republic of Korea was overrun. Then you pleaded for the help of the Free World. It came. The United Nations acted and the United States responded quickly and largely to its appeal on your behalf. We responded because we believed in the principle of free world unity.

The principle of unity cannot work without sacrifice. No one can do precisely what he wants. The youth of America did not do what they wanted. Over one million American boys have left their homes and families and their peaceful pursuits, to go far away to Korea. They went because, at a dark hour, you invoked the sacred principle of free world unity to save your country from overwhelming disaster …

Your nation lives today, not only because of the great valor and sacrifices of your own armies, but because others have come to your side and died besides you. Do you now have the moral right to destroy the national life which we have helped save at a great price? Can you be deaf when we now invoke the plea of unity?57

The call for unity and the moral outrage against Rhee’s actions were echoed around the world. London’s Daily Mail condemned Rhee for his “treacherous” and “insolent” act, which brought up “a simple, but all-important question: Who is to be in charge in South Korea, the United Nations or Syngman Rhee?” If an armistice failed to materialize, “such is the enormity of Rhee’s offense,” it declared. “He has demonstrated he is not to be trusted. He should be replaced by someone with a sense of responsibility. If necessary, his whole Government should be bundled out.” London’s Daily Herald was similarly outraged: “The present position is utterly intolerable and the disaster for the world would be incalculable.” India’s Delhi Express stated that “Rhee should be removed at once to a place far from the scene of mischief.” The Times of India responded that “the situation calls for an all-out action to save peace,” while Tokyo’s Jiji shimpō suggested that the United States depose of “the unscrupulous dictator.”58

Only the communists reacted coolly. They wanted to end the fighting. Their letter to Clark in early July included the usual vitriol against the Syngman Rhee “clique” for “unscrupulously violating the prisoner of war agreement,” but the letter, signed by both Kim Il Sung and Peng Dehuai, nevertheless ended on an upbeat note: “To sum up, although our side is not entirely satisfied with the reply of your side, yet in view of the indication of the desire of your side to strive for an early armistice and in view of the assurances given by your side, our side agrees that the delegations of both sides meet at an appointed time to discuss the question of implementation of the armistice agreement and the various preparations prior to the signing of the armistice agreement.”59 An uncharacteristically generous response, it indicated the communists’ determination to conclude an armistice. The communists also saw Rhee’s provocative actions as an opportunity to splinter the U.S.-ROK alliance. In their assessment and response to the current state of armistice negotiations, the Soviet leadership suggested that the Chinese “achieve a common point of view with the U.S. on the issue of an armistice in order to isolate Rhee … and deepen the domestic and foreign differences of the American side.” It was a policy that Kim Il Sung would continue to exploit in his future dealings with the United States. As the Chinese Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Wu Xiuquan later quipped, “In this case, a paradoxical situation will be created inasmuch as we and the U.S. are sort of acting together against Syngman Rhee.”60

A grim Eisenhower opened an emergency National Security Council meeting on June 18 lamenting “the terrible situation” for UN forces. How could UN forces “conduct the defense of South Korea while ignorant of what ROK forces in their rear would do next?” he asked. If the UNC was unable to trust Rhee, “how can we continue to provide ammunition for the ROK forces when we have no idea what their next move would be?”61 Removing Rhee, an option considered, no longer seemed possible. He had gained enormous domestic prestige for his bold defiance. Getting rid of him could create a politically explosive situation that could lead to mass defections within the ROK Army. The only viable option was negotiation to get South Korea to agree to the armistice. Walter Robertson, the assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs, would lead the American team. U. Alexis Johnson, the deputy assistant secretary of state overseeing Japan and Korea policy, later said, “In Robertson, Rhee had met his match. Garrulous, earthy, charming as it was possible to be, Robertson could out-talk even Rhee; and his voice had the kind of soothing richness that could tame even this crochety mono-maniac.”62

Robertson was optimistic. Rhee told him that his arrival in Korea was “like a hand to a drowning man.” Robertson reported to Dulles that Rhee was “a shrewd and resourceful trader” who was also “highly emotional, irrational, illogical, fanatic, and fully capable of attempting to lead his country into national suicide.” Still, Robertson believed there was room for compromise. If the Americans could not persuade Rhee to accept an armistice, they would scare him into compliance. Eisenhower told the National Security Council on July 2 that “we can do all sorts of things to suggest to Rhee that we might well be prepared to leave Korea, but the truth of the matter is, of course, that we could not actually leave … We must only take actions which imply the possibility of our leaving.”63 The new Eighth Army commander, Lt. Gen. Maxwell Taylor, who replaced General Van Fleet in January 1953, announced on July 6 plans “for the withdrawal of American and British divisions from the battle line with or without the cooperation of the South Korean Army in the event of a truce being signed with the communists.”64 The story was picked up by newspapers around the world, including The Times of London, which reported, “An inspired dispatch from Washington even speaks of a possible withdrawal of American and allied forces; and the expectation in the United Nations is that, unless Mr. Rhee is brought to terms, the United Command will proceed to the signature of an armistice without him.”65 Patience and politicking paid off. On July 9, Rhee indicated that he was prepared to cooperate with the United States and not disrupt the armistice talks. In exchange, Rhee received “informal assurances” that the U.S. Senate would ratify the mutual security treaty and provide additional economic and military support. Rhee’s bold move had paid off handsomely. Dulles later confided that “we had accepted it [mutual security treaty and aid] as one of the prices that we thought we were justified in paying in order to get the armistice.”66

With the prospect for peace just around the corner, the communists decided to give Rhee a “bloody nose” just to make sure he would not try another ploy to disrupt the armistice agreement. On July 13 they launched their final offensive. ROK II Corps was driven back six miles and suffered more than ten thousand casualties. The communists had made their point. General Paek Sŏn-yŏp later noted, “The outcome of the Kŭmsŏng battle had dealt a serious blow to the President’s prestige.”67 The attack undermined Rhee’s credibility that ROK forces could face the Chinese alone. The Chinese had called Rhee’s bluff, and thereafter there was no more talk of South Koreans going north.

There was one final obstacle to the signing of the armistice: inside the wooden building in P’anmunjŏm where the armistice was to be signed hung a copy of Picasso’s The Dove, a painting that had been adopted by the communists as their symbol of peace. Clark ordered this “Red Symbol” removed. After a heated exchange, Picasso’s Dove painting was finally covered up.

At 10:00 a.m. on July 27, 1953, Lt. Gen. William Harrison, the Eighth Army deputy commander who had replaced Admiral Joy as chief UN delegate in May 1952, and Lt. Gen. Nam Il signed the eighteen-page armistice agreement. They did so in twelve minutes and in complete silence. When finished, they simply got up and left without saying a word. “That’s the way it had been throughout the negotiations,” said Clark later. “Never during the talks did the delegates of either side nod or speak a greeting or farewell during the daily meetings.”68

Immediately afterward, the document was taken to Clark at his forward headquarters in Munsan. Three hours after the signing in P’anmunjŏm, Clark sat down at a long table in front of newsreels and TV cameras to sign the document again. He then addressed the audience:

I cannot find it in me to exult in this hour. Rather, it is time for prayer, that we may succeed in our difficult endeavor to turn this armistice to the advantage of mankind. If we extract hope from this occasion, it must be diluted with the recognition that our salvation requires unrelaxing vigilance and effort.69

Many in Korea shared Clark’s ambivalence. “The cease-fire caused a measure of anguish in the officers and men of the South Korean army because it perpetuated the division of our nation,” wrote Paek. “The lengthy armistice negotiations had given us enough time, however, to accept the reality that we could do nothing about it.”70 There were no victory celebrations in the United States, no cheering crowds in Times Square, no sense of triumph. “The mood,” wrote one observer, “appeared to be one of apathy.”71 Yet Eisenhower considered the armistice to be one of his greatest achievements. He had promised to go to Korea and end the killing and this he did. Although Stalin’s death and other events played a greater role in ending the war than either Eisenhower or Dulles ever cared to admit, the president had nevertheless put his prestige behind the settlement. He also knew that only a Republican president could have done it. The same settlement coming from a Democratic administration, especially one that had been blamed for “losing” China, would have had a far more divisive effect on the country.72 Still, the armistice did not resolve the fundamental problem that had precipitated Kim Il Sung’s invasion of South Korea. The nation remained divided.

Although the killing had stopped, the war continued, solidifying cold war arrangements for the next fifty years. The Korean War has officially outlasted the cold war, since no formal peace treaty between the belligerents has been signed, and it has persisted in influencing global events, giving birth to a new world order that would directly impact not only the politics and societies in America and China, but also those in the East Asian region and beyond.