I would suggest to you that if we had not gone into Korea, I think it would have been very unlikely that we would have gotten into Vietnam.

—GEORGE BALL, July 19861

We are duty-bound and obliged to defend a friendly ally from Communist aggression, just as the 16 allies of the free world, led by the United States, saved us in the Korean War of 1950.

—PARK CHUNG HEE, February 19652

By 1965 the Sino-Soviet split had become obvious. But these new developments did not mean that the communist threat to the free world had diminished in any way. Both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations saw the split and Sino-Soviet competition in the communist world as actually leading to greater efforts on the part of Moscow, and Beijing, to exert communist control over the Third World. “We see stepped up attempts to subvert, to undermine, and to spread Communist revolution,” the elder statesman W. Averell Harriman observed.3 Staunch anticommunists like W. W. Rostow echoed the same theme: “The impulse in Moscow to seek the expansion of Communist power is so deeply rooted and institutionalized that Soviet leaders will feel an almost historic duty to exploit gaps in the capacity, unity and will of the West.”4

It is not surprising that the Kennedy administration saw the fate of Vietnam tied to new concerns about communist activities in the Third World. These concerns were carried over into the Johnson administration after Kennedy’s death in November 1963. In a key speech on April 7, 1965, Johnson explained why America had to be involved in Vietnam. Directly, America had a moral duty to honor the pledge made at the Geneva Conference in 1954 to protect Vietnamese independence. More broadly, Vietnam was part of the American commitment to protect the free world order, and stopping the communist threat in Vietnam was especially vital to halting the Chinese threat to that order. “The central lesson of our time is that the appetite of aggression is never satisfied. To withdraw from one battlefield means only to prepare for the next,” Johnson passionately stated.5 William Bundy, assistant secretary for Far Eastern affairs, echoed the charge:

We recognize the profound implications of the Sino-Soviet split and the possibility that it may lead to greater tensions between the U.S.S.R. and Communist China in the northern regions. But we doubt that the U.S.S.R. has yet abandoned her Communist expansionist aims, and certainly not to the point where in the foreseeable future she could be relied upon to play a constructive role in assisting other nations to defend themselves against Communist China … And let us recognize too that, to the extent that Soviet policy has changed, or may change in the future, this will be in large part due to the fact that we, in partnership with other free-world nations, have maintained a military posture adequate to deter and to defeat any aggressive action. We do not aim at overthrowing the Communist regime of North Vietnam but rather at inducing it to call off the war it directs and supports in South Vietnam … If Hanoi and Peiping prevail in Vietnam in this key test of the new communist tactics of “wars of national liberation,” then Communists will use this technique with growing frequency elsewhere in Asia, Africa and Latin America.6

America’s challenge in Vietnam was to prevent these “wars of national liberation” from spreading. When asked in April 1965 how Americans could hope to compete with China in influencing Southeast Asia, “which is virtually a Chinese backyard,” Secretary of State Dean Rusk replied, “Why not? These countries in Southeast Asia have a right to live out their own lives without being overrun by the outside … their national existence depends upon it. If we were to abandon that idea then the great powers would—what? Revert to the jungle?”7 For Rusk the problem of South Vietnam essentially boiled down to a replay of the war in Korea: North Vietnam, with the backing of China and the Soviet Union, was waging a war of aggression against a sovereign state.

In 1954, as senator, Johnson, along with Senator Richard Russell Jr., the chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, had been the loudest and strongest opponent of American military intervention in Indochina. And yet, as president, Johnson embarked on a series of intervention actions in Vietnam, the sort he had advised Eisenhower against a decade earlier. Why? Why had the “lessons” of Korea, which had provoked such a strong reaction by members of the “Never Again Club” and Congress against American involvement in Indochina in 1954, now emerged as a preeminent consideration for intervention in 1965?

Part of the answer had to do with the fact that perceptions of the Korean War had changed. The frustrations over the inconclusive and protracted nature of the war in Korea had, by the mid-1960s, been tempered by time, while the communist threat in Asia had at least been contained. The Korean intervention was viewed through the prism of the wider global cold war struggle and was eventually cast as an American victory.8 Korea had become an example where the battle line for freedom had been successfully drawn and had stood firm.

By the time of President Kennedy’s death, in November 1963, there were sixteen thousand American advisors and support troops in Vietnam. Three weeks earlier, the president of South Vietnam, Ngo Dinh Diem, was killed in a military coup that had been quietly sanctioned by Washington. Johnson had inherited a chaotic and unstable situation in Vietnam made all the more difficult because his interests and strengths were not in foreign affairs but domestic policy. According to McGeorge Bundy, who served as the national security advisor to Kennedy and Johnson, Johnson’s main concern during the first months of his presidency was the upcoming 1964 presidential elections, which “served as powerful deterrent for Johnson to take any definitive action regarding American commitment to Vietnam.” For a year Johnson was tremendously constrained, as he could ill afford a major escalation of the Vietnam conflict during an election year, but neither could he afford to lose South Vietnam and be blamed for a communist victory on his watch. “My own impression, then and through the early summer, was that he [Johnson] wanted firmness and steadiness in Vietnamese policy, but no large new decisions,” Bundy recalled.9

The opportunity to show his serious commitment to Vietnam came on August 2, 1964, when the North Vietnamese attacked an American destroyer in the Gulf of Tonkin. Two days later, new gunboat attacks were reported. Although doubts were later raised about whether a second attack had actually occurred, Johnson responded by ordering retaliatory raids against North Vietnam. The incident provided Johnson with enough leverage to extract from Congress almost unlimited authority to escalate American involvement in Vietnam. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution that Congress passed gave the president the authority to respond to any armed attack against the United States without congressional approval. Johnson attempted to quell concerns over this unprecedented presidential power by reassuring the American public that “we still seek no wider war.” In a speech on August 5, he declared, “To any who may be tempted to support or to widen the present aggression, I say this: there is no threat to any peaceful power from the United States of America. But there can be no peace by aggression and no immunity from reply.”10 The resolution provided the president with just enough political cover to convince the American people that he was tough on communism without appearing overly belligerent.

Johnson won a landslide victory that November. Domestic political considerations continued to shape his decisions on Vietnam. On the one hand, he feared that Vietnam would drag down his domestic agenda. He was keenly aware that the stalemated war in Korea had prevented Truman from seeking a second term. At the same time, he thought that “losing” South Vietnam to the communists would damage his power and America’s credibility and standing in the free world. The Vietcong had stepped up their military pressure, and by the spring of 1965 it appeared that all of South Vietnam was on the verge of being overrun by the communists. The choice was remarkably stark: withdraw or escalate. The Korean analogy largely informed how Johnson thought about the two issues.11

Advocates of a negotiated neutralization of South Vietnam and eventual American withdrawal included two influential Democratic senators, Richard Russell of Georgia and Wayne Morse of Oregon. Russell was convinced that the U.S. mission in Vietnam was doomed and that negotiations and withdrawal were the only viable options. He warned the president that Vietnam “would be a Korea on a much bigger scale and worse.” He also heeded the historical lessons of the French colonial wars. “The French reported that they lost 250,000 men and spent a couple of billions of our dollars down there and just got the hell whipped out of them.” When Johnson brought up the subject of bombing North Vietnam, Russell retorted, “Bomb the North and kill old men, women and children? … Oh hell! That ain’t worth a hoot. That’s just impossible … We tried it in Korea.”12 Senator Morse was also pessimistic about the American ability to make any headway in Vietnam. He had voted against the Tonkin Resolution, one of just two senators who chose to defy the president, and challenged every major assumption underlying Johnson’s Vietnam policies. “The policy of what we called helping the Government of South Vietnam control a Communist-inspired rebellion has totally failed,” he wrote in February 1965. “I do not foresee a time when any Government in South Vietnam that is dependent upon the United States for its existence will be a stable or popular one.” Instead, Morse advised, “we should be seeking some kind of settlement that will carry out the 1954 objective of removing foreign domination from the old Indo-China, but this time with an effective guarantee of international enforcement.”14

George Ball and President Johnson, July 14, 1966. During the Second World War, Ball had been a member of the United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSB) team that was charged with studying the effects of bombing Germany and Japan. The survey found that “the German capacity to produce armaments of war had increased through the end of 1944 despite progressively expanded allies sorties.” In addition, it found that the resolve of both the German and the Japanese population to resist the enemy had not been broken. The conclusion of the survey disturbed Ball and would later affect his thoughts about the bombing of North Vietnam.13 (LBJ PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY)

Undersecretary of State George W. Ball agreed. As Johnson’s “favorite dove,” Ball had been an early and consistent opponent of American escalation.15 Having worked closely with the French during the Indochina war, he had seen firsthand the futility of that conflict. He was also deeply alarmed by the resolution. Sensing that Johnson would win a landslide victory and worried that a decision on Vietnam was fast approaching, Ball wrote his thoughts in October 1964 in a long memorandum titled “How Valid Are Our Assumptions Underlying Our Vietnam Policies.”16

The main thrust of the memorandum was to show that the Korean War analogy was wrong and even dangerous in thinking about Vietnam. In a section titled “South Vietnam Is Not Korea,” Ball argued that Seoul in 1950 had a stable government ruled by a leader who wielded strong political control over the population. This was not the case in South Vietnam in 1964. In South Korea, Americans had fought under a United Nations mandate. No such mandate existed for South Vietnam. Moreover, the Korean War had begun with a massive invasion and was fought as a conventional war. In South Vietnam there was no such clear-cut invasion, only a “slow infiltration that many nations regarded as an ‘internal rebellion.’”17 “In approaching this problem,” he wrote, “I want to emphasize one key point at the onset: the problem of South Vietnam is sui generis. South Vietnam is not Korea, and in making fundamental decisions it would be a mistake to rely too heavily on this Korean analogy.”18 Instead, Ball argued that the far more valid, and sobering, comparison was the French experience in Indochina between 1945 and 1954. Based on that, he favored a gradual withdrawal of American military forces from South Vietnam.

When Johnson finally gave the memorandum serious consideration in February 1965, it was already clear that Ball never had a chance. Johnson had already made up his mind that an American withdrawal from Vietnam was not a viable option. “It was useless for me to point out the meaning of the French experience,” Ball later wrote. “They thought the French experience was without relevance. Unlike the French, we were not pursuing colonialist objectives but nobly waging war to support a beleaguered people. Besides, we were not a second-class nation trying to hang on in Southeast Asia from sheer nostalgic inertia; we were a superpower—with all that implies.”19 Since the purported goal was to help the South Vietnamese defend themselves against communist tyranny, how could moral comparisons between French and American aims in Vietnam even be considered? The strongest arguments for withdrawal, however, actually came from the military. The Joint Chiefs had found themselves in the same position as Ball with regard to the escalation of the war. Johnson’s military advisors warned him that “it would take hundreds of thousands of men and several years to achieve military stalemate.” If war was to be waged there, then Johnson was urged to mobilize the reserves “and commit the United States to winning the war.”20

This was essentially the same argument that General Ridgway had given to President Eisenhower in 1954: if the United States was not prepared to pay the cost in blood and treasure that would be incurred by a guerilla war in Vietnam, then such a war must be avoided. In effect, the arguments against escalation by both Ball and the JCS wrestled with the Korean War analogy in different ways to make a similar point. Ball said the war in Vietnam was fundamentally different from the Korean situation because Saigon in 1964 was not Seoul in 1950. He warned that a war to prop up a failing regime in the face of the Vietcong’s increasing success would result in the loss of American prestige. The Joint Chiefs, on the other hand, worried that Vietnam was too much like Korea because it would lead to another inconclusive and stalemated war. It might also risk another war with China and lead to World War III.

The president weighed his options carefully before deciding his next move. However, it was the domestic political implications of the Korean War analogy that vexed Johnson the most. “For LBJ,” McGeorge Bundy later confided, “the domino theory was really a matter of domestic politics.” Vietnam was “an American political problem, not a geopolitical or cosmic matter.”21 Very simply, Johnson did not believe that his administration could survive the loss of South Vietnam. His credibility was at stake. “I am not going to be the President who saw Southeast Asia go the way that China went,” he told Henry Cabot Lodge, U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, shortly after assuming power.22 As a product of Texas of the 1950s, Johnson was defined by the Korean War era and the fear of appearing “soft” on communism. “Those fears and suspicions of the Communists had never entirely left him,” David Halberstam observed, “and they colored the way he understood the challenge of Vietnam.”23

At the same time, Johnson was keenly aware that Truman’s real fall from grace was brought about by the stalemate in Korea. Eisenhower had capitalized on the Korean tragedy to secure his landslide victory in 1952. “It looks to me like we are getting into another Korea,” a distraught Johnson told McGeorge Bundy in the spring of 1964. “I just don’t think it’s worth fighting for 10,000 miles away from home and I don’t think that we can get out. It’s just the biggest damn mess I ever saw.” Bundy tried to reassure the president. He could fight in Vietnam and still protect his domestic agenda. “Thirty-five thousand soldiers had died in the Korean conflict over a three year period, at a rate roughly comparable to the death toll in Vietnam,” he said. “Yet there was no protest.” The Korean War had been “a hard choice but incontestably right, both in morals and politics.”24 The American people would see it that way too.

Bundy’s assumptions are revealing. The notion that the American people would simply accept the war in Vietnam as a necessary replay of Korea demonstrated the extent to which the legacy of that war still informed the Johnson administration’s foreign policy. Bundy declared that “to abandon this small and brave nation to its enemy and to the terror that must follow would be an unforgiving wrong … [It] would shake the confidence of all these people in the value of the American commitment.”25 What Bundy had failed to address, however, was that the times had changed: the two apparent monolithic constructions of the 1950s were in the process of breaking apart. An overt rebellion by France was taking place in one camp, while another rebellion by China was taking place in another. It was now possible for a member of the Western bloc to be either “American” or “Gaullist” just as it was possible for a member of the Communist Party to be “Russian” or “Chinese.”26 So where did this leave the notion of credibility underlying the domino theory and America’s policy in Vietnam?

Years later McGeorge Bundy admitted that he should have challenged the logic of the domino theory when he had the opportunity as national security advisor. In his memoirs, President Johnson claims to have harbored no such doubts. His primary concern had always been how the fate of South Vietnam would adversely affect his domestic agenda.27

In February 1965, Johnson ordered a limited bombing campaign of North Vietnam called Operation Rolling Thunder. Six changes of government in South Vietnam had already occurred in 1964, and three more took place in the spring of 1965. The Vietcong saw their opportunity and had stepped up military pressure, pushing South Vietnam to the verge of collapse. Johnson made the fateful decision of introducing a substantial number of ground troops in March, to protect U.S. air installations. Subsequently, more troops were added to conduct offensive operations in the areas around U.S. air bases. A critical moment of decision had finally been reached. Disastrous South Vietnamese military defeats in the spring led to a series of crisis-driven inspection visits and White House meetings to determine what if anything should be done. By the summer of 1965, the Pentagon requested an increase of 100,000 troops, bringing levels there to 175,000 to 200,000. In six months, the Pentagon projected the need for another 100,000.28 By the end of 1966 the number was 385,000 and by 1968, at its height, the total U.S. commitment stood at 536,000 military personnel.

Johnson later wrote that his decision to gradually increase the levers of war was due to fear of China’s reaction; calling up the reserves and publicly committing the United States to a full-scale war in Vietnam might have precipitated another Korea-like confrontation. Yet it was clear from the beginning that Chinese leaders had sought to avoid a direct Sino-American clash and would only intervene if the United States had invaded North Vietnam. The Chinese had learned from the Korean War experience too, and repeatedly and publicly communicated their intentions so that there would not be any confusion.29 Moreover, as Ridgway and others later argued, if Johnson had been really worried about such a confrontation, he should have clearly stated the main objectives of the war at its onset. “With our aims loosely described only as ‘freedom for the people to choose their way of life’ or as ‘standing up to communism,’” Ridgway later complained, “we have drifted from a point where we were told, a scant two years ago, that our military task would be largely accomplished and our troops withdrawn by December 1965, to a point where the faint outline of half-million troop commitment becomes a distinct possibility. And even that commitment is not offered as a final limit.”30

The accumulation of difficulties and the costs of the war also meant that the stakes rose. When his liberal allies began to abandon him, Johnson felt betrayed. What he had failed to realize was how much the world had changed since the Korean conflict. Had Johnson been truly convinced that the fall of South Vietnam posed an imminent threat to America’s national security, as Truman believed about South Korea, he would have embarked on a full-scale commitment to the war from the very beginning. That he failed to do so, deciding instead to wage a major war virtually in secret, speaks volumes not only about his growing doubts regarding the “lessons” of Korea, but also about his impotence in challenging their main assumptions.

While a handful of nations sent token forces to Vietnam to join in support of the United States, they did not come close to duplicating the “Uncommon Coalition” of the Korean War. The largest and most meaningful partner was South Korea, which provided both substantial military support and political coverage for the Americans. The height of South Korea’s involvement reached its maximum strength in 1968, with over 50,000 military and 15,000 civilian contract workers. The ten-to-one ratio of U.S. to South Korean manpower is misleading because, in fact, 20 percent of the infantry combat forces under U.S. control were South Koreans, a situation rarely appreciated or acknowledged. As during the fighting in Korea, most of the Americans were part of the tail—a tail that also supported the Koreans—while the majority of the Koreans were part of the teeth. Moreover, as U.S. forces began to draw down in 1968, and would be almost all out by early 1973, the South Koreans remained in force until after the Paris Peace Accords were signed in January 1973, effectively serving as the rear guard of the American withdrawal.31

These military efforts were led by Gen. Park Chung Hee, who came to power in May 1961, a year after the South Korean people toppled Syngman Rhee in a watershed event known as the April 1960 Revolution. Postwar South Korea in the 1950s was a terribly depressing place, a “hopeless case of poverty, social anomie and political instability.”32 The war had devastated the country. Although Rhee had leveraged South Korea’s strategic position in the cold war to wheedle hundreds of millions of dollars in military and economic aid from the United States, he had little to show for his efforts, as much of the aid was siphoned off to line the pockets of corrupt officials. Nearly a decade after the war, the country, with its tiny domestic market and thoroughly aggrieved population, still lacked sources of domestic capital. The North Korean threat, which had justified the stationing of large numbers of American troops in South Korea, was not only a military security concern. In 1961, North Korea’s gross national product (GNP) per capita was $160, twice that of the South, posing dire psychological and political threats as well.33 A review of U.S. policy toward South Korea in 1957 revealed that it was then “the largest beneficiary of American aid in the third world.” The Americans wanted to reduce this dependence but could not do so until South Korea became able to grow its economy. Postwar South Korea seemed headed to a future of poverty, dependence, corruption, and despair.34

Park Chung Hee (seated), as a Manchurian Army officer. (SAEMAŬL UNDONG CENTRAL TRAINING INSTITUTE)

Yet one substantive outcome of the war was the creation of a modern South Korean military that had swelled from 100,000 in 1950 to well over 600,000 by 1953. The once-fledging force was transformed by the war into an experienced modern formidable fighting organization. It was also adept at solving large-scale logistical problems. This allowed ROK military leaders to boast that their level of managerial skills was “ten years ahead of the private sector.” In addition, the military could claim that it was the most democratic institution in South Korean society. Many of its leaders were of humble origins, “and its organization acted as the melting pot for men of diverse social and economic backgrounds.”35 The South Korean military was, in the words of one historian, “the strongest, most cohesive, best-organized institution in Korean life,” and by 1961 it had decided to make its power known.36

Park Chung Hee became the chosen agent to lead his nation out of its current crisis. After graduating at the top of his class from the military academy of the Japanese puppet state Manchukuo in Manchuria in 1942, he was selected to spend two years at the Japanese Military Academy near Tokyo, where he graduated in 1944. He was then assigned to the Eighth Manchurian Infantry Corps, essentially a Japanese-controlled unit, where he fought anti-Japanese guerilla bands, many manned by Koreans. After Korea’s liberation in 1945, Park joined the Korean Constabulary, which subsequently became the ROK Army. His link to the Japanese colonial regime as a soldier in the Japanese military would haunt him after he became president, but it was his membership in the leftist SKWP that almost cost him his life. In the hotbed of postliberation politics, Park followed his older brother, an ardent communist, and became a member of the party. He was later caught up in the purging of leftists and communists from the ROK Army after the Yŏsu-Sunch’ŏn Rebellion in late 1948. Arrested, interrogated, and facing a death sentence, he was saved by then Colonel Paek Sŏn-yŏp, also a graduate of the Manchukuo military academy and in charge of rooting out leftists in the ROK Army, and by KMAG advisor Capt. James H. Hausman. Both sensed something extraordinary about the future president. After serving time in prison, Park returned to work for the ROK Army as a civilian. Given his spotty background, he would probably not have amounted to much had it not been for the outbreak of the Korean War, which gave him the much-needed opportunity to prove his loyalty to South Korea. Just fourteen months after his discharge and days after the North Korean invasion, Park was reinstated into the ROK Army as a major.37

Park, however, was not a communist but rather an ardent nationalist and pragmatist. He easily overthrew the corrupt and ineffective government of Rhee’s successor, Chang Myŏn, in a bloodless military coup on May 16, 1961. Chang had come to power after the April Revolution, but his administration also floundered. When Park took over, he immediately issued a “revolutionary platform” that called for the eradication of “all social corruption and evil,” the creation of a new “national spirit,” and a “self-supporting economy.” Park sought to change it all, justifying his actions in terms of a “surgical operation.” “The Military Revolution is not the destruction of democracy in Korea,” he declared in March 1962. “Rather, it is a way of saving it; it is a surgical operation intended to excise a malignant social, political and economic tumor.” Koreans, he said, must embark on a “new beginning” by bringing an end to Korea’s long history of “slavish mentality” toward strong foreign countries, including the United States, and achieving national independence. In this he shared with his North Korean nemesis, Kim Il Sung, the same drive for economic and military self-sufficiency that they both linked to overcoming the people’s historical “subservient” mentality toward foreign powers. Just as Kim had steadfastly worked to increase his independence from the Soviet Union and China, Park sought to gain independence from the Americans by “eradicating the corruption of the past and by strengthening the people’s ability to be autonomous.”38

Thousands of citizens jam City Hall Plaza in Seoul to pledge their support for the military government’s anticommunist and austerity programs, May 1961. (AP PHOTOS)

The coup was wildly popular. Most people enjoyed seeing corrupt officials and businessmen being paraded down the street with dunce caps and sandwich cards declaring “I am a hoodlum” and “I am a corrupt swine.” Park’s cleanup efforts were so effective that even liberal skeptics greeted the coup with unabashed admiration. The liberal monthly journal Sasanggye published the kind of laudatory reaction to the military’s “clean-up” operation that was typical. It congratulated the coup leaders “for making the citizens respect the law, reinvigorating sagging morale, and banishing hoodlums.”39 At the same time, however, Park needed these businessmen “hoodlums” to help him jump-start the flagging economy, so he offered them a deal: no jail time if they invested their “fines” in building up new industries to sell products in foreign markets. Park wanted to build an export-based economy. His efforts paid off, and in 1963 he legitimately won the presidential election, marking the end of the junta that had led the nation since the May 1961 coup. This in turn provided him with the political legitimacy he needed to govern effectively and with the U.S. backing he would have to rely on to help fund his national development program. But Park and the nation needed time to recover. What Park feared most was the withdrawal of American troops from the Korean peninsula before South Korea was ready to stand on its own against North Korea. His fears were not unwarranted. In 1961, President Kennedy had seriously considered reducing U.S. forces in South Korea.

The Vietnam War provided the opportunity for Park to begin to realize his goal of achieving national independence and security, even though the price of this autonomy meant aligning South Korea’s interests with U.S. security interests in East Asia. Although Park had railed against his country’s dependence on Washington, he was quick to recognize the enormous opportunities afforded by South Korea’s commitment of a large combat force to the war in Vietnam. There was the public relations of joining an idealistic and moral anticommunist crusade as a member of the free world. There was also the leverage, from the commitment of Korean blood, he could use to maximize U.S. economic and military aid to fulfill the national priority of securing Korea’s autonomy. At the same time, by rallying the nation in support of another war against communism, Park reopened old wounds. His crusade in Vietnam and the ongoing threat from North Korea would become powerful sources of domestic mobilization in support of his economic and national security policies. Park would refight the Korean War in Vietnam to win the nation’s economic autonomy from the United States and to secure itself from the threat of another war with the North.

“Hoodlums” are paraded through the streets on May 23, 1961. The sign reads, “We will give up our hooligan lifestyle and lead a clean life.” (AP PHOTOS)

Korea’s interest in Vietnam goes back to 1954, when Syngman Rhee offered to send a division to Vietnam in the wake of France’s disastrous defeat at Dien Bien Phu in May. Two months later the French were out with the signing of the Geneva Accords. Rhee’s motivation was twofold. The most obvious was to demonstrate Korea’s appreciation for the help it had recently received from UN forces in the Korean War. The other motive was more personal: “a burning desire to mobilize an anti-communist front in Asia under his leadership and to court U.S. opinion,” as characterized by Ellis O. Biggs, U.S. ambassador in Seoul at the time.40 Given Rhee’s character, it seems rather certain that the latter motive was the dominant one, as he had been under a cloud in American and world opinion, especially over his actions in the final months before the armistice. The Americans at first favorably considered Rhee’s offer but ultimately rejected it, owing to the difficulties of supporting the force in Vietnam, but more important was the potential political backlash from the American public, who might question why U.S. troops remained in Korea if South Korea could afford to send forces to Vietnam.41

Park also made an early offer of troops, in mid-November 1961, during his visit to Washington, the first by a South Korean head of state. It had barely been five months since the coup, and Park was still a general and the chairman of the junta known as the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction. The CIA’s report on his communist ties before the Korean War raised suspicions, but the Kennedy administration gambled that he was the genuine article, and therefore someone who could lead Korea into a democratic and self-reliant nation. Park’s visit was a personal triumph and solidified and legitimized his position as Korea’s leader. He was greeted upon his return by a wildly cheering, flag-waving crowd of half a million lining the road from the airport.42 The State Department informed the American embassy in Seoul that “Chairman PAK’s [sic] visit successful in achieving results hoped for … Chairman made very good impression on U.S. officials with whom he came in contact. Appeared dedicated, intelligent, confident, fully in command his govt, and quite aware of magnitude of problems he faces … Informal visits elsewhere in U.S.… enhanced favorable image of Chairman among Americans generally and together with Washington visit received generally very good press.”43 In response to President Kennedy’s question on whether Park had any thoughts about Vietnam, Park responded that he realized the situation was grave and that his country stood ready to assist the United States in sharing the burden to resolve it.44 Park’s motives are uncertain but are suggested by the circumstances of the infancy of his regime, its shaky legitimacy, and the desire to be in America’s good graces not only to ensure continued aid but also to reverse its decline, the principle objective of his trip. But there was no explicit American request for troops nor was any given, and by mid-1962 aid levels had gone down, and the United States was considering again a partial drawdown of forces in Korea.45

The continuing uncertainties in Korea itself did not help. The junta was still the government, although elections were promised by the end of 1963. Also causing significant problems were the negotiations over the normalization treaty with Japan. Normalization of relations with Japan was an emotional and enormously unpopular issue with the Koreans, who periodically staged mass demonstrations against it. The end of Japanese colonialism was too recent, and the grievances too much to overcome with a simple treaty. But for Park, opening the gates to Japanese grants, loans, and technology was key to fulfilling his economic plans, so he was determined to finalize the treaty. After much uncertainty, a general election was held in November 1963 to choose a president and representatives to the National Assembly. The elections seem to have been fair according to reporting from the American embassy.46 Park won the presidency, and his party won the majority of seats in the Assembly. Having retired from the army before the elections, Park now had a genuine civilian government, and a political base to achieve his vision for “National Restoration.”

After a suspension of talks, owing to the political uncertainties in Korea, negotiations with Japan resumed in early 1964. With the stability of a newly elected civilian government in South Korea, which also represented continuity of the previous junta regime, the Japanese felt secure enough to continue the talks. It also helped that Park was sympathetic to Japan, not only because he had been an army officer in the Japanese colonial regime, but also because he looked to Japan’s modernization path since the mid-nineteenth century as a model for Korea. Although Japan saw little to gain from normalizing ties with Korea, indeed it would have to pay compensation for its actions during the colonial period, the United States exerted extraordinary pressure since 1961 on both sides to conclude a treaty. This policy was based purely on the aim of creating a Northeast Asian anticommunist bulwark anchored by Japan and with Korea on the mainland. Ideally, Japan would replace the United States as a proxy of containment in the region, and normalization of Japanese–South Korean relations was sine qua non to getting there.

One final set of issues animated this situation. By the early 1960s Japan had essentially fully recovered from World War II economically. Trade with the United States was a key to sustaining its rapid economic growth. But the economic success of Japan’s export machine began to cause friction with its former overseer, and numerous trade and tariff issues began to affect U.S.-Japanese relations. There was also the question of Okinawa, which remained under U.S. occupation and which Japan wanted to get back as soon as possible (it did so in 1972). Improving trade relations with the United States to stay on the path to greater prosperity and reclaiming Okinawa were the two overriding Japanese foreign policy goals at the time.

In 1964–65 the Vietnam War and the Japan-Korea normalization treaty converged. The American escalation and need for troops from Korea, Korea’s eagerness to reverse the trend of American aid and open the gates to Japanese funds and technology, and Japan’s desire to smooth trade relations with the United States and resolve the Okinawa situation dynamically interacted, creating a situation of great complexity. The best outcomes for Park were a close and beneficial relationship with the United States through support in Vietnam, to ensure South Korea’s security, and a treaty with Japan to kick-start economic development.

The opportunity came when Park was asked for a contribution of military aid as part of President Johnson’s More Flags campaign in April 1964. Korean support in Vietnam could serve three main purposes, according to historian Jiyul Kim: “to further cement U.S.-ROK relations through alliance and aid; to serve as insurance for that relationship should the normalization talks with Japan break down; and, to increase Korea’s and Parks’ regional and international importance and influence.”47 Park’s offer was a modest one—a mobile army surgical hospital (of 130 personnel) and a ten-person Taekwondo instructor team—but these personnel represented almost a third of the total response (500 from a dozen countries) to the More Flags campaign. Only Australia, with its 167 advisors, exceeded the Koreans in number.48 By adopting an option for increasing military pressure if North Vietnam remained intransigent in negotiations, a new plan approved by Johnson in December 1964 paved the way for the escalations of 1965.49 The plan also meant a renewed American effort to solicit additional international assistance. Park, to American elation, agreed to provide a 2,000-person engineer unit for civic projects.50 This was a substantial addition to the 23,000 Americans in Vietnam at the end of 1964. The renewed U.S. pleas to get “More Flags” from other countries did not do well. South Korea was the only nation to answer the call.51

At the end of April 1965, Johnson approved the next dramatic escalation, additional ground forces consisting of nine U.S. battalions (a division), three ROK battalions (a regiment), and an Australian battalion, with the possibility of a further twelve U.S. battalions (division plus regiment) and six ROK battalions (two more regiments to make a ROK division).52 A Korean contingent thus became an integral and vital part of the overall plan. The deployment of the ROK and Australian forces was not yet confirmed, but 50,000 more Americans were put in the pipeline to join the 23,000 already in Vietnam, to bring the total to almost 75,000. By early June, the military situation had seriously deteriorated, and the Americans anticipated a large-scale Vietcong offensive that threatened to overrun South Vietnam. General William Westmoreland, commander of Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV), the top U.S. command in Vietnam, made an urgent request for a further 100,000 soldiers, consisting of thirty-four U.S. battalions (almost four divisions), nine ROK battalions (one division), and one Australian. Westmoreland’s plan to use this force to stabilize the situation and then go on the offensive was approved.53 It was this request that led to intense deliberations and a decision in July 1965 to approve Westmoreland’s request for 100,000 troops, then another 100,000 in early 1966, and the possibility of several hundred thousand more beyond, thus decisively committing and escalating the American intervention in Vietnam and opting for a military solution. The number of soldiers in MACV ballooned from 23,000 Americans, 140 Koreans, and 200 Australians in early 1965 to 180,000 Americans, 21,000 Koreans, and 1,500 Australians by the year’s end. By the end of 1966 the command would include 385,000 Americans, 45,000 Koreans, and 5,000 Australians, as well as a small force from New Zealand.54

In May 1965 Park made a state visit to Washington, his first as president. Dean Rusk recalled later, “There was a personal rapport between President Johnson and President Park.”55 Park provided strong assurances that Korea would be able to send a military division to Vietnam even though no official request had been made, much less approved by the ROK National Assembly. Furthermore, negotiations over the normalization treaty with Japan had progressed sufficiently enough so that a final agreement was imminent. Park could now envision the realization of his grand plan for South Korea.

General Creighton Abrams, a U.S. commander in Vietnam, presents the U.S. Presidential Unit Citation to the commander of the Cavalry Regiment of the ROK Capital “Tiger” Division, for actions performed by its Ninth Company, Qui Nhon, Vietnam, September 9, 1968. (U.S. NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION)

Nevertheless, doubts about sending South Korean troops to South Vietnam still lingered over the potential cost in lives and the reduced sense of security until the deployed troops could be replaced (and they eventually were, many times over). In a dramatic legislative special session in mid-August 1965, members of the minority party, who opposed both the treaty and the troop bill, resigned and walked out in protest after the majority party, Park’s party, forced the treaty legislation to a plenary vote. It passed almost unanimously in their absence. The following day the troop bill also passed unanimously. Interestingly, the troop bill was debated before the vote, and pointed questions were raised about the nature of the war and whether it could be won, the same questions that George Ball had raised in opposing escalation. It was an indication that what ultimately mattered was not stopping communism in Vietnam per se, but the leverage that the deployment could provide in obtaining concessions from the United States.56

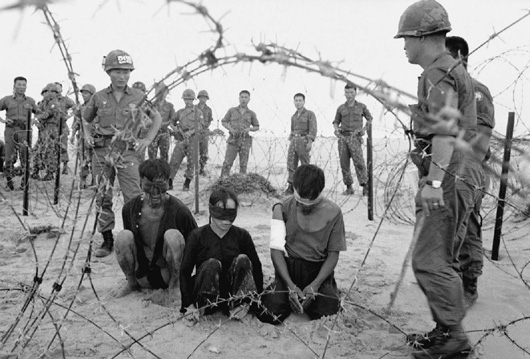

Soldiers of the South Korean White Horse Division (Ninth Infantry Division) with Vietnamese prisoners near a village in the Hon Be mountains near Tuy Hoa, November 30, 1966. (AP PHOTOS)

The Korean division-size contingent consisting of two army regiments and a marine brigade deployed just two months later. In 1966, in line with another large expansion of American forces, the More Flags campaign was laid out again. The Koreans responded with another division of 24,000 men. The terms for deploying the second division, emphasizing economic incentives rather than military aid, were qualitatively different from the terms of the first deployment. According to U.S. Ambassador William Porter’s testimony to the Senate in 1970, the total direct benefit of the war to South Korea between 1965 and 1970 was approximately $930 million, a significant portion of foreign exchange earnings and of the GNP.57 By the end of the war, over 5,000 South Koreans had died and 11,000 had been wounded in Vietnam.58

When Park came to power in 1961, South Korea was one of the poorest nations in the world in terms of per capita GNP, and it was completely dependent on the United States. By the end of 1966 South Korea was well on its way to becoming a self-sufficient regional economic and political power. James C. Thomson, a key Asia policy advisor on the National Security Council, wrote in June 1966 that “political instability, economic doldrums, and isolation from its neighbors have given way to robust and relatively stable democracy, economic take off, and full participation both in [the] Viet-Nam war and Asian regional arrangements.”59 Two months later in Seoul, Ambassador Porter observed that Korea had “traditionally been a country which looked backward rather than forward, looked inward rather than outward, evaded or deflected relationships with other countries rather than initiated or influenced them … [but now] to a new self-confidence has been added a new outlook and a new attitude toward the outside world in which Korea now conceives of herself as playing an important part.”60

For the first time since the opening of Korea in the late nineteenth century, the nation had garnered the world’s respect. The year 1966 was a watershed for South Korea and a personal triumph for Park, owing to the country’s role in the Vietnam War and the normalization treaty with Japan. Economically the GNP growth rate increased from 2.2 percent in 1962 to 12.7 percent in 1966, starting a trend for one of the longest sustained periods of high growth of any nation in history.61 By the end of 1966, the South Korea–Japan trade was the largest in volume in Asia. Complementing the market was U.S. economic aid, which increased from $120 million in 1962 to $144 million in 1966. With regard to security, the ROK armed forces’ rapid program of modernization, including new weaponry for ground, air, and naval forces, significantly boosted the nation’s capacity to defend against any renewed North Korean hostility. U.S. military aid increased from $200 million in 1961 to $247 million in 1966 and reached $347 million in 1968. Washington also gave a firm promise not to draw down U.S. forces without consultation.62 Of great symbolic importance was the signing of the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) in July 1966, which defined Korean jurisdiction over U.S. troops. Until the agreement was signed, American forces essentially operated under extraterritorial rules. Koreans, therefore, had no legal right to prosecute any crimes committed by American soldiers against a Korean. The State Department observed that “the question of even-handed treatment was particularly important in early 1965 when we were asking the Koreans to participate to a greater extent in the struggle in Viet-Nam … our actions relating to the SOFA were designed to assist the ROK evolve from a client state into a self-reliant and self-confident ally.”63 Perhaps the greatest value to ROK security was the combat experience gained by its armed forces in Vietnam.

The political and diplomatic achievements of 1966 were perhaps even more impressive. In June 1966, Seoul hosted the inaugural meeting of the Asia Pacific Council (ASPAC), with delegations from all noncommunist Asian nations. It was the culmination of Park’s dream for it had been his initiative, a venue for South Korea to take a leading role in a new regional organization dedicated to fighting communism and focused on China. ASPAC did not last long—it disbanded in 1975 after the fall of Saigon and the establishment of U.S.-China ties—but it was able to provide one of the strongest statements of Asian-Pacific (Australia and New Zealand were members) support for the U.S. policy in Vietnam. James C. Thomson gleefully reported, “A plethora of regional and sub-regional cooperative initiatives has evolved: ASPAC, ADB (Asia Development Bank, to be organized in November) …, which hold great promise for future Asian resolution of the region’s own problems. Most important, our own view that our presence in Viet-Nam was buying time for the rest of Asia is now shared by the Asians themselves.” President Johnson credited Park on the idea for the conference in his memoirs.64

At the end of October 1966, after a swing through Southeast Asia, his second for the year, Park participated in the Manila Conference hosted by Johnson “for a review of the war … and for a broader purpose—to consider the future of Asia” with countries that had forces in Vietnam. Johnson continued his Asian trip with a state visit to Korea the following week, the first by a serving U.S. president. He reassured the Koreans that the United States was making all possible efforts to harden Korean defenses by modernizing its armed forces and that “the United States has no plan to reduce the present level of United States forces in Korea.”65 It was a triumphal moment for Park. In November the Asia Development Bank was established in Tokyo, with South Korea as one of the charter members.66 By the end of 1966, though still poor and underdeveloped, South Korea and Park bathed in the glow of these international achievements. Security, prosperity, and influence were now within reach and the possibilities for the future seemed limitless. Vietnam had given South Korea an opportunity to refight the battle against communism, and in the process had laid the foundation for South Korea’s spectacular economic growth.

It was under these circumstances that Kim Il Sung, wary that the South would soon catch up to the North, declared renewed provocations to foment a communist revolution in the South. Embarking on a Korean-style “Vietnam strategy” of infiltrating spies and armed guerillas into the South, with the aim of establishing revolutionary bases and inciting instability there, Kim also began to invest a large amount of his nation’s resources on a military buildup. It was the beginning of a new phase of the Korean War marked by intense competition and conflict between the Kim Il Sung and Park Chung Hee regimes for the mantle of Korean legitimacy.