By 1968, the strategic environment that led to America’s involvement in Korea and Vietnam had drastically changed. The “surprise” Tet Offensive in January 1968 shocked the American public and turned them against the war. A dispirited President Johnson decided to forgo running for a second term, halt the bombing of North Vietnam, and begin peace talks. At the same time, the threat of monolithic communist power was receding following the Sino-Soviet split, Sino-American rapprochement, and the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam by early 1973. It was in this new political and strategic environment that the Korean War entered a new phase. This period, from the late 1960s to the late 1980s, saw an intensified “local” struggle between the two Koreas that had little or no impact on the world at large. Faced with a precipitous decline in its economic fortunes, and realizing that South Korea was overtaking North Korea economically, Kim Il Sung launched a series of provocative actions in 1968 and 1969 against South Korea and the United States in a last-ditch effort to foment a South Korean revolution and achieve reunification under his control. The most daring acts were a commando raid to assassinate President Park (which failed) and the capture of the USS Pueblo, within three dramatic days in late January 1968. In October 1968, more than a hundred North Korean commandos landed on the east coast to organize the local peasants and fishermen to spark a communist revolution. In April 1969, the North Koreans shot down an unarmed U.S. reconnaissance plane, killing several-dozen Americans. Between 1967 and 1969, the DMZ was declared a combat zone because of increased North Korean military actions.

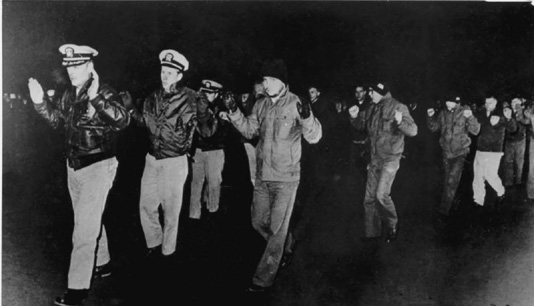

The localized confrontations amounted to a competition—economic, military, and psychological—between the two systems and their competing visions of modern Korea. By the late 1960s, peaceful reunification of Korea on P’yŏngyang’s terms seemed unlikely. In addition, continued U.S. military presence in South Korea, the strengthening of the South Korean military, and Japan’s rapid growth were serious threats to Kim’s increasingly shaky regime. With the U.S. and significant South Korean forces committed in Vietnam, Kim saw a chance to try again for reunification by force. Neither the Soviet Union nor China had any interest in Kim’s plans. Only once did the situation briefly become of global concern again. This was the ax murder incident in 1976, when North Korean soldiers killed two U.S. officers at the Joint Security Area in the DMZ. The U.S. military response was an overwhelming preparation for large-scale military confrontation.

Kim’s provocations had severe repercussions for U.S.-ROK relations. Washington’s lukewarm response to the North’s attempt on Park’s life contrasted with its hyperreaction to the capture of the USS Pueblo. Both responses were based on Washington’s desires not to risk renewed fighting in Korea when it was bogged down in Vietnam, and to get the Pueblo crew released. The Nixon doctrine, announced in July 1969, also shocked Park. It essentially stated that nations must rely primarily on their own capacity to secure their defense rather than rely on U.S. power. Park began to think that South Korea must be prepared to defend itself without American support. These feelings were reinforced by Nixon’s détente policy with China and the Soviet Union, dramatically demonstrated with a visit to China in February 1972 and to Moscow in May 1972. Soon thereafter, Nixon forced South Vietnam to accept the Paris Peace agreement signed in January 1973, which marked the end of American involvement in Vietnam. For Park, these events signaled America’s betrayal of its three principal anticommunist partners in Asia: Taiwan, South Vietnam, and South Korea. In the 1970s Park embarked on a major effort to build up heavy industries tied to an indigenous arms industry. North and South Korea also intensified their diplomatic competition around the world by trying to upstage the other in claiming to be the more legitimate Korean regime.

It was during this “local” phase of the war that America’s first post–Vietnam War president was elected to office. Soon after announcing his candidacy in 1975, Jimmy Carter called for a phased and eventually complete withdrawal of U.S. forces from South Korea. Carter’s rationale was based not only on a perception of low North Korean threat and the adequacy of South Korean military capacity, but also on his disgust over the Park regime’s human rights abuses. Ultimately, President Carter was unable to fulfill his campaign promise. The North Korean threat turned out to be much greater than had previously been known. In addition, the American presence in South Korea had become an indispensable source of regional stability during a period of intensified conflicts among communist nations over national interests and historical issues in Asia. Carter’s plan was privately opposed by the Soviet Union and China. Beijing, paranoid about the Soviet threat, was particularly nervous because it saw the removal of American forces as tempting the Soviets to reassert their long-standing interest over the Korean peninsula. The Russians wanted continued American presence to maintain the precarious balance of influence over North Korea and to restrain Kim Il Sung from restarting the war. Ironically, the unfinished Korean War had become necessary to maintaining the peace on the Korean peninsula.