One of the more remarkable feats of Kim Il Sung was that he was able to survive the Korean War at all. The North Korean people rightly wondered what the war had accomplished other than the complete destruction of their country. “So many men of military age perished in the war,” wrote the historian Balázs Szalontai, “that women far outnumbered men in North Korea until the 1970s.” While soldiers sought refuge from the incessant bombing campaigns in the damp and overcrowded tunnels, they also faced another enemy that proved just as deadly: tuberculosis. It is estimated that as many as a quarter of a million demobilized NKPA soldiers had serious infections. Considering that the total troop strength at the start of the war was roughly 135,000, this is an appalling number. “In the last six months of the war,” wrote one North Korean physician, “more people died of tuberculosis than on the front.”1

The number of civilian deaths from tuberculosis is not known, but without proper equipment—one North Korean hospital treating fifteen hundred tuberculosis patients did not have a single X-ray machine—or adequate medical staff, civilians must have succumbed to the disease by the tens of thousands. One study calculated that the total population of the DPRK in 1949 stood at 9.622 million, but owing to either death or emigration, it decreased by 1.131 million during the war.2 Hundreds of thousands of acres of farmland had also been decimated, along with nearly three-fourths of residences. Seventy percent of North Korea’s trains and 85 percent of its ships had been destroyed during the war, making the country’s transportation system almost inoperable.3

Despite such destruction, the country had survived, but the North Korean people were aware that it was no thanks to the NKPA or Kim Il Sung. Chinese troops had carried the main burden of the war, while the NKPA had been reduced to a mere supporting role. Chinese influence in North Korean affairs had predictably increased, giving rise to tensions and resentment among North Korean leaders. Ironically, it was the Chinese role in the war that provided new opportunities for Kim to maintain his grip on power. The Soviet Union’s domination of North Korean society since 1945 had been severely curtailed by the war and by the Chinese presence on the peninsula. Kim used this situation to his own advantage. Many Soviet Koreans had served as general officers in key positions both during and after the war, and there was a predictable backlash against them, a logical outcome of defeat since Soviet Koreans had never been entirely accepted into North Korean society.

The first sign of Kim’s new strategy to strengthen his leadership position was his decision to attack Hŏ Ka-i (Alexei Ivanovich Hegai), the highest ranking Soviet Korean in the North Korean government and a founding member of the North Korean Workers’ Party (NKWP). Hŏ was removed from his post as first secretary when China entered the war, and demoted to deputy prime minster, a significant drop in status and power. Taking advantage of the temporary leadership vacuum in the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death in March 1953, Kim decided to get rid of Hŏ. On July 2, 1953, Hŏ was found dead, allegedly by his own hand, but the suicide had the appearance of a setup.4 Shortly after the armistice, Kim also began to target the Yanan faction, Koreans who had served with the Chinese communists during their civil war. Although he was selective in purging leaders of this group, given that Chinese forces continued to remain in North Korea until the late 1950s, Kim nevertheless was bold enough to take on Gen. Mu Chŏng (Kim Mu-chŏng), the best-known member of the Yanan faction, for his alleged role in the unsuccessful defense of P’yŏngyang in October 1950. Mu, however, was able to avoid the fate of a mysterious suicide; he was simply expelled from the party and later sought asylum in China, where he remained for the rest of his life.5

Although the removal of Hŏ Ka-i and Mu Chŏng weakened Chinese and Russian influence, Kim waited until 1956 to embark on a wholesale purge of either group, as he was not yet prepared to alienate them and risk cutting off aid or even direct intervention. The South Korean communists who had moved north, however, had no such foreign protector and were thus the first to be completely purged. A week after the armistice was signed, the first show trials began in P’yŏngyang. On August 3, twelve leading members of the SKWP were tried on counts of espionage, sabotage, and conspiracy. Four days later they were found guilty, and in one fell swoop, Kim Il Sung had managed to eliminate the entire southern faction from the North Korean leadership.6 The North Korean leader spared the leader of the group, his close associate Pak Hŏn-yŏng, however. He was placed in solitary confinement and “tried” two years later. On December 15, 1955, Pak was sentenced to death and executed.

In the front row, from left to right, Ch’oe Yŏng-gun, Pak Hŏn-yŏng, and Kim Il Sung, P’yŏngyang, 1952. This photo was probably taken by a foreign visitor, which explains the odd composition with Kim barely in the frame. It may also be indicative of the low esteem Kim was held at the time. Also noteworthy is the prominent display of both Stalin and Mao in the background. Fearful of plans to oust him from power, Kim instigated a full-scale attack against the Domestic faction in 1953. This group had originally hailed from the south, and its members had been prominent leaders in the South Korean Workers Party (SKWP) before they were purged or moved north after the ROK’s founding in 1948. Foreign Minister Pak Hŏn-yŏng, the most prominent member of the domestic faction, was arrested in 1953. Accused of being an American spy, he was tried and executed in 1955. (COURTESY OF THE HUNGARIAN NATIONAL MUSEUM)

In 1955, Kim Il Sung introduced the guiding philosophy of his regime, which remains to this day the foundational political tenet of North Korea. Addressing the Presidium of the Supreme People’s Assembly, the highest organ of power according to the North Korean Constitution, on December 28, Kim delivered his first speech about chuch’e (literally translated as “master of one’s body” or “self-determination”).7 He spoke of the need to study Korean history and culture. Why were Koreans looking at foreign landscapes and studying foreign literature when Korea had its own rich beauty and literary traditions? he asked. He attacked the Nodong sinmun newspaper, the NKWP organ, for blindly copying headlines from Pravda, and condemned its former editor, Ki Sŏk-bok, a Soviet Korean, for harboring “a subservient attitude toward the Soviet Union.” Kim also accused Soviet Koreans of being “dogmatic and fundamentalist in their emulation of the Soviet Union” by their strict adherence to the Moscow line. “To make revolution in Korea we must know Korean history and geography as well as the customs of the Korean people,” he declared. “Only then is it possible to educate our people in a way that suits them and to inspire in them an ardent love for their native place and their native motherland.”8 The speech was significant in other ways as well. References to the “glorious Soviet Army that liberated Korea” and “the Soviet Union, savior of all oppressed nations,” that had been part of the standard history of North Korea were gone. The “little Stalin” who was “expected to act under the wise protective shadow of the ‘big Stalin’ in Moscow” was replaced by a man of “unusual naïve spontaneity,” loving, innocent, and sincere, in short, a man who embodies truly Korean virtues.9

By early 1956, an all-out campaign to weaken Soviet political influence had begun in earnest. Contacts by Soviet Koreans with the Soviet embassy were discouraged. Special permission to meet with “foreigners,” a code word for the Russians, had to be obtained. The number of Korean-language Radio Moscow programs was cut in half. The role and presence of the Korean Society for International Cultural Exchange, the primary conduit for spreading Soviet culture, were greatly diminished. “Local branches were closed down, the collection of personal membership fees halted and control of its profitable publishing section was transferred to the Ministry of Culture.” Later that spring, the NKWP Central Committee ordered the end of all performances of Russian plays in Korean theaters. The Institute of Foreign Languages, the primary source of Russian-language education, was closed. Russian was no longer taught to college students. Also notable was that the “Month of Soviet-Korean Friendship” was not celebrated in 1956. It had been one of the largest events in North Korea since 1949 and had not even been canceled during the war.10 Finally, Kim declared that “his partisan activities to have been the vanguard of the Korean communist revolution,” sidelining the vital roles that the Soviet Union and the Soviet Koreans had played in the creation of the NKWP.11 Soviet embassy official S. N. Filatov observed that many Soviet Koreans were growing increasingly worried about the situation in North Korea. According to Filatov, “praise of comrade Kim Il Sung is especially widespread in both oral and print propaganda in Korea and if anyone comments on this matter, they are subject to punishment.” Soviet contribution to the liberation of Korea, and its vital role in the founding of the NKWP, were being seriously distorted.12

The first overt challenge to Kim’s anti-Soviet moves came during the Third Congress of the Workers’ Party of Korea, held in P’yŏngyang in late April 1956. Emboldened by Khrushchev’s speech in February 1956 denouncing Stalin, critics of the regime began to mobilize themselves against Kim Il Sung’s dominance of the NKWP.13 Pak Ŭi-wan (Ivan Park), a Soviet Korean and the vice premier and minister of light industry, was a leading member of this group.”14 Ch’oe Ch’ang-ik, a prominent leader of the Yanan faction, also began making moves against Kim. He complained that the group’s great contributions to the revolutionary struggle against Japan and the war effort against the Americans were not being properly recognized by the North Korean leadership.

Ch’oe Ch’ang-ik addresses the Third Congress of the Workers’ Party of Korea in April 1956. Ch’oe was an early challenger of Kim’s personality cult, and he pressed for economic reforms. He was later executed in 1960. (COURTESY OF THE HUNGARIAN NATIONAL MUSEUM)

The biggest source of concern, however, was not simply the marginalization of Soviet Koreans or the Yanan faction, but the distinct “lack of criticism or self-criticism within the North Korean leadership.” Opponents of the regime had become wary of Kim’s growing personality cult and the uncritical acceptance of his economic directives. “There is no collective leadership in the Korean Worker’s Party,” Yi Sang-jo, the North Korean ambassador to the Soviet Union, complained. “Everything is decided by Kim Il Sung alone, and the people fawn over him.”15

The challenge came during the August 1956 NKWP plenum, where Yun Kong-hŭm, another leading member of the Yanan faction, directly criticized Kim. “Yun said that the CC [Central Committee] of the KWP does not put the ideas of Marxism-Leninism into practice with integrity and dedication,” Pak Ŭi-wan later recalled. But Kim’s supporters vigorously counterattacked. Calling Yun “a dog,” they defended Kim and asserted that “the democratic perversion inside the party” was the “legacy of Hŏ Ka-i and did not pertain to the practical work of Kim Il Sung.” Yun was immediately condemned as a “counterrevolutionary,” and Kim demanded that he be “removed from the ranks of the CC, expelled from the party and put on trial.”16 Soon thereafter, Yun and his band of rebels fled to China. Their “coup” had failed. It was a defining moment for the Great Leader. He had successfully withstood an internal challenge from the party.

Backlash against Kim’s foes, real and imagined, ensued. The opposition appealed directly to the Soviet Union and China for help. Ambassador Yi wrote to Khrushchev on September 5 requesting that he send “a senior official of the CC CPSU [Communist Party of the Soviet Union] to Korea to convene a CC Plenum of the [North Korean] Workers Party … [where the] intra-party situation is to be studied … and comprehensive and specific steps worked out directed at removing the shortcomings in our party.”17

Concerned by the developments in North Korea, Khrushchev and Mao decided to act. On September 23, a joint delegation led by Soviet statesman Anastas Mikoyan and the Korean War Chinese commander Peng Dehuai arrived in P’yŏngyang. Peng’s contempt for Kim Il Sung was well known. The two had clashed many times during the war, and Peng, according to a 1966 Soviet report, was “not ashamed to express his low opinion of the military capabilities of Kim Il Sung.”18 Mao was also disdainful of the North Korean leader. According to one Soviet official who accompanied Mikoyan to P’yŏngyang, Mao told Mikoyan that Kim started an “idiotic war and himself had been mediocre.”19 The entire episode was an excruciatingly humiliating experience for Kim Il Sung. He was forced to convene a new party plenum in September, where he had to criticize himself and revoke his decisions from the August plenum and reinstate purged opposition leaders.20 He was also warned against further purges. When the delegation left a few days later, it appeared that a thoroughly chastised Kim had been forced to mend his ways and embark on a new course.

But Kim was unexpectedly saved by events in Eastern Europe. Stalin’s death in 1953 and then Khrushchev’s dramatic denunciation of the man and his policies in early 1956 set in motion Eastern European reform movements to gain independence from Soviet domination and liberalization of its political-economic system. Events moved rapidly. Violent public demonstrations in Poland that summer reached a climax in mid-October with the selection of a previously purged moderate communist leader, despite Khrushchev’s personal opposition and threat of intervention. Developments in Poland inspired Hungarian students, whose spontaneous demonstrations in support of the new Polish leader sparked a nationwide uprising. Khrushchev faced a mounting crisis in two of the most important members of the Soviet bloc. The new Polish leader was able to assure Khrushchev that greater autonomy and reform did not mean giving up communism or leaving the Soviet orbit, and obtained a modus vivendi. Khrushchev’s concession in Poland was also encouraged by his increasing concern over the much larger and more dangerous situation developing in Hungary. By the end of October, reform forces had led an armed insurrection, which violently overthrew the government and announced its intention to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact. A few days later Soviet troops already stationed in Hungary intervened and crushed the uprising, at a cost of twenty thousand Hungarian lives. Several hundred thousand Hungarian refugees fled to the West. Mao, who had bristled at Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin, had advised a violent suppression of the Hungarian revolt. The limits of Khrushchev’s liberalization had been crossed, and the Soviet Union tightened its grip over central Europe.21

Fortunately for Kim, the Soviet intervention in Hungary created a backlash in North Korea against the exonerated rebels in the September plenum. The Soviet reaction in Europe raised the possibility of a similar reaction by the Kremlin against North Korea. Would the North Korean rebels who had demanded Kim’s removal and called for political liberalization be crushed too? The timing of the Hungarian crisis was fortuitous in other ways as well. China was undergoing its own domestic political turmoil with the launching of its Anti-Rightist campaign. It would be difficult for Mao to support those who railed against the personality cult in North Korea that Mao had embraced for himself in China. Moreover, following the events in Hungary, the Chinese leader began to have second thoughts about the wisdom of backing North Korean dissidents against Kim. Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization initiatives had seriously called into question the competence and wisdom of Soviet leadership. Mao was also wary of seeing Kim Il Sung replaced by those who might develop strong ties with the Soviet “revisionists.” Hence, by November 1956, Mao had decided to firmly reject these initiatives. There would be no Hungarian Revolution in China nor would China support a similar revolution in North Korea.22

Khrushchev was caught by surprise by the events in Hungary and Poland. They were cautionary tales on the dangers of liberalizing too rapidly. He also decided to reject the North Korean dissidents’ plea for help. In supporting the status quo, Khrushchev could at least take satisfaction that Kim had eliminated the Yanan faction, an act that presumably increased the Soviet Union’s position. Moreover, he could not be sure that in the event of Kim’s removal, the new North Korean leader would favor the Soviets over the Chinese. The Soviet leader had little appetite to risk another confrontation with Mao over Korea. For all these reasons, Khrushchev decided not to interfere in North Korea’s domestic affairs. “The small spark of the Hungarian uprising was possibly sufficient to burn the buds of the North Korean democracy,” observed the Soviet Korean Hŏ Chin, who later fled to the Soviet Union.23 Henceforth, the purge of real and imagined supporters of the Korean opposition “gained official recognition and unconditional approval.”24

The scale of the purge between 1958 and 1959 was large. Nearly one hundred thousand “hostile and reactionary elements” were rounded up, imprisoned, and executed. Andrei Lankov noted that this number represented roughly the number of “enemies” exposed between 1945 and 1958. Therefore, “within just nine months of 1958–1959, more people were persecuted on political grounds than during the entire first thirteen years of North Korean history.”25 Kim emerged from the August 1956 challenge unscathed and strengthened. Recalling these events in 1965, he saw the moment as a decisive one in North Korean history. It was the moment, he said, when the party had triumphed over “outside forces”: “At that time the handful of anti-Party factionalists and die-hard dogmatists lurking within our Party challenged the Party, in conspiracy with one another on the basis of revisions and with the backing of outside forces.”26

By 1961, Kim Il Sung was firmly in control of North Korea. Such a turn of affairs would never have been tolerated under Stalin, but Khrushchev really had no alternatives. When the Hungarian ambassador to North Korea, Jozsef Kovacs, asked Vasily Moskovsky, the newly appointed Soviet ambassador, why the Soviet Union acquiesced to Kim’s behavior, he was told that the Soviets were forced to accommodate Kim Il Sung’s “idiosyncrasies” because of the Soviet Union’s antagonistic relationship with China. “In the policy of the KWP and the DPRK one usually observes a vacillation between the Soviet Union and China,” he told Kovacs. “If we do not strive to improve Soviet-Korean relations, these will obviously become weaker, and at the same time, the Chinese connection will get stronger, we will make that possible for them, we will even push them directly toward China.”27 The Sino-Soviet rivalry over North Korea, as elsewhere in the world, was seen as a zero-sum game.

In December 1962, Kim adopted a “military line” that called for “modernizing and strengthening North Korea’s military capacity” to reunify the peninsula through an unconventional war unlike the conventional war he tried in 1950.28 It was the culmination of Kim’s thinking about developments in the South since Park Chung Hee’s coup in May 1961. Unlike his predecessors, Rhee and Chang, Park was a military man. His ambitious vision for South Korea based on accelerated economic development and expanded military capability was linked to what was undoubtedly a much more competent strategic vision toward the North and the future of the peninsula. Kim thought it inevitable, given Park’s background, his vision, and the South’s much larger population, that time was running out to reunify the peninsula under his terms. Moreover, ominous signs of economic stagnation in North Korea were beginning to appear in the mid-1960s, owing to faulty economic policies and greatly increased spending on the military. This happened precisely as the South Korean economy began to take off under Park. By the late 1960s it became clear that it would simply be a matter of time before South Korea would catch up with the North, economically and militarily. The longer North Korea waited, the stronger South Korea would become. The North Korean regime, it was reported, was following with “growing anxiety the developments in South Korea where younger, more flexible state leadership has been able to bring the country [back] from the brink of total collapse after the fall of Syngman Rhee.”29 The North Korean Seven-Year Plan (1961–67), introduced with great fanfare in September 1961, was therefore designed to build up the North Korean economy and military to fulfill the goals of the “military line” policy in order to initiate a new war to communize the South. This war was compelled by the ongoing legitimacy wars between Kim in the North and Park in the South. Since each leader claimed to be creating their version of a prosperous and internationally respected nation, the question became which nation, the North or the South, was representative of the “true” Korea. Kim had to make sure to win this legitimacy war before South Korea became too strong to challenge him on that front. “Unification cannot be delayed by one hour,” he declared in 1966. “Liberation of the South,” he stated, was “a national duty.”30

During the 1950s, it appeared that North Korea was winning this contest of legitimacy. With the help of the Soviet Union and other socialist states, it had achieved rapid economic strides, recovering from the war and reconstructing the nation. In fact, North Korea had attracted so much attention as a “model” socialist state that many wealthy Korean families living in Japan decided to return to the socialist fatherland and begin a new life there.31 North Korea’s GNP was also higher than the South’s and would remain so until the mid-1960s. Nevertheless, there were already signs that this growth rate could not be sustained. Production rates began to slow down or, in some cases, were reversed.32 Internal deficiencies in the North Korean system and overdependence on foreign aid accounted for much of the decline. The Soviet Union financed the lion’s share of nonrepayable assistance, although China also contributed huge sums of aid both during and after the war.33 This aid had played a decisive role in Kim’s reconstruction plans, but it did little to help establish a strong foundation on which to build North Korea’s economy, which was becoming overpoliticized. “The issue of political guidance was of single and exclusive importance in resolving any problem,” complained one Hungarian official. “The rise of careerists and people of that ilk, and the thrusting of the few technical experts into the background and their designation as politically unreliable on fictitious charges, is a common occurrence.”34 As the pace of economic growth slowed, industrial output declined further. One analysis noted that “in 1966, industrial output had declined 3% over the preceding year, the first time in North Korea.”35

By this time, it had become clear that Kim’s chuch’e economy had reached its limits.36 His dream of creating an autarkic economy turned out to be an unrealizable and self-contradictory enterprise because it led to more dependency, not less. As the historian Erik van Ree pointed out, a country that tries to produce almost everything it needs “spends a tremendous amount of energy in the task of supplying the domestic market.” This, in turn, causes problems with productivity and inefficiency. Moreover, the limitation of a small domestic market like North Korea’s also makes it very difficult to specialize. Without specialization, it becomes impossible to pursue a vigorous export policy and to take advantage of the international markets. The result is a lack of innovation and a scarcity of funds.37 Consequently, North Korea had no alternative but to rely on the influx of large amounts of foreign aid as its only strategy for economic growth. But even large influxes of foreign funds could not offset the inevitable slowdown of North Korea’s economy, which was caused by the strict adherence to the orthodox Stalinist concept of all-around development and national self-sufficiency.38 Ironically, Kim’s chuch’e economy required continuing inputs of foreign funds with no expectation of repayment, the exact opposite of the independent national economy achieved by South Korea.39 Yet, despite all these problems, the North Korean leadership “thwarted any attempt to reformulate political and economic concepts even within the given socialist model.”40

At the same time, Kim began to mobilize the entire population for work. In 1958, he launched the ch’ŏllima movement, which was based on the massive use of “voluntary labor.” The historian Balázs Szalontai noted that “generally speaking, at the end of 1958, people had to do four to five hours of unpaid work every day, in addition to the eight-hour workday.” In an ambitious speech Kim Il Sung gave at the Workers’ Congress in September, the North Korean leader declared that the Five-Year Plan (1956–61) should be filled in just three and a half years. Agricultural cooperatives pledged to increase harvests, while factories also promised to double their 1958 outputs in just one year. Yet, for all the back-breaking labor, basic living standards hardly improved. Part of the reason for this was the low quality of the yields. In some cases, North Korean factories were mass-producing products that were defective, and yet they continued to produce them anyway to fulfill abstract quotas.41 While the mobilization campaigns put tremendous strain on the already overworked population, they did not overcome the problems of productivity and inefficiency inherent in a collectivized system.

As the Park regime’s political and economic fortunes rose rapidly by the end of 1966, owing to the Vietnam War and the normalization treaty with Japan, the number of incidents along the DMZ underwent a dramatic intensification in 1967, “reaching about 360 by September as opposed to a total of 42 in 1966.”42 Szalontai reported that by July of that year, Kim Il Sung was already preparing for the assassination of Park Chung Hee. Kim’s new militant strategy also appeared to be behind his decision to promote military cadres within the NKWP in October 1966, which was then followed by a massive purge of many high-ranking officials as well as several prominent party members in 1967. It is likely that the purge of these leaders was linked to their disagreements with Kim’s new militant strategy.43

As Kim was escalating his attacks against the South, the battle for legitimacy also took on an international dimension as Park began to directly challenge Kim in the forum of world opinion. Both leaders engaged in diplomatic wars to secure support for their regime in the form of special goodwill missions that crisscrossed the continents and oceans. “The Korean Question” of establishing a unified and democratic Korea through peaceful means had been an agenda item since 1947, but it took on far more significance by the mid-1960s because of the wave of decolonization and new member states in the UN after World War II.44 From 51 member states at its founding in 1945, the UN had expanded to 122 by 1966.45 South Korea saw the UN as the most important venue for settling the Korean question and for gaining its legitimacy by becoming a full member.46 Thus, starting in 1966, South Korea made extraordinary efforts to garner the maximum number of votes for the UN resolution approving South Korean membership by dispatching goodwill missions worldwide, but in particular to young nations in Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. North Korea countered with missions of its own starting in 1968, albeit on a smaller scale. Sometimes a keystone cops–like scene took place when a South Korean mission would arrive just as a North Korean mission was departing, or vice versa.47

Most importantly, the legitimacy battle waged between the Kim Il Sung and Park Chung Hee was linked to the political question of foreign presence, and especially military forces, in South Korea. Kim had always insisted that the withdrawal of all foreign troops from the Korean peninsula was a prerequisite to achieving peaceful reunification. He had much to gain from this position since the Soviet troops had departed from North Korea in 1948, and the Chinese had by 1958. Furthermore Kim claimed to have purged all those who had worked with the Japanese during the colonial period, while South Korea’s Park had himself served in the Japanese army. Kim also claimed that while North Korea had achieved true national autonomy, South Korea was still a “puppet” controlled by and living under the yoke of “foreign occupation.” By casting the struggle between North and South Korea in terms of a struggle for national sovereignty, Kim asserted the existence of a “revolutionary movement in South Korea” ready at any moment to topple the Park regime.48

Kim seems to have truly believed that the Park regime could be toppled from within. His plan first called for finishing the North Korean revolution by completing its military-industrial base. Simultaneously, the military part of the campaign would begin through the use of unconventional forces (special operations, agitators, and guerillas) to harass the Americans “on every front,” including off the peninsula, to strain their commitment to the South by stretching their forces worldwide and thereby break the U.S.-ROK alliance.49 Once the South Koreans were free of their “puppet master,” they would be liberated either by fomenting a revolution or through a conventional invasion.50 Kim had formulated a fantastically ambitious plan. While completing military and economic goals, he also meant to reunify the peninsula.51

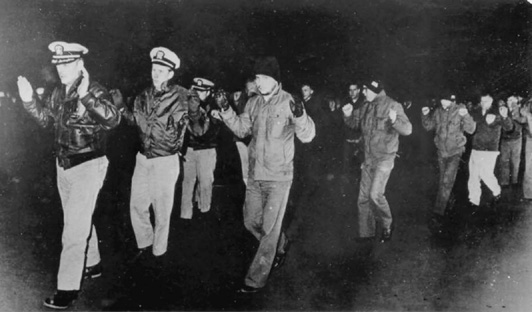

In this photo, released by the U.S. Navy, crew members of the USS Pueblo are seen in captivity. This photo has become an iconic image in North Korean propaganda and is repeatedly used in North Korean posters to show North Korea’s “triumph” over a humiliated United States. (AP PHOTOS)

The consequences of the new policy were immediate and startling. The share of the military budget “rose from an average of 4.3 percent during 1956–1961 to an astonishing annual average of 31.2 percent in 1967–69.”52 The expansion of the defense sector caused shortages of manpower and raw materials in the nondefense sector of the economy. Production quotas lagged far behind the unrealistic targets of the Seven-Year Plan, and Kim was forced to ask for more Soviet aid. Eager to encourage North Korea’s disengagement from China, the Soviets obliged. While Kim “took the Soviet Union for a cow he could usefully milk in order to keep his regime afloat,” the Soviet Union was satisfied that it could “keep the North Koreans from the Chinese embrace.”53

On January 21, 1968, North Korea tested the limits of Soviet friendship when it sent thirty-one commandos across the DMZ on a mission to assassinate Park at his official residence, the Blue House. Two days after the failed assassination attempt, North Korea raised the stakes even higher with the capture of the USS Pueblo and its crew off the North Korean coast but still in international waters. Its seizure provoked a condemnation by the Johnson administration and raised the possibility of renewed full-scale fighting on the Korean peninsula.54

“The key question,” wrote the New York Times on January 28, 1968, was “why did they do it?” Why did North Korea risk war with the United States and invite international condemnation to capture a ship that posed little threat?55 “What made the Pueblo incident particularly disturbing was that it came after more than a year of stepped up North Korean military pressure against South Korea,” the New York Times continued. There was as yet a lack of understanding or appreciation of Kim’s new campaign. There were speculations that Kim was laying the groundwork for greater military action “so that seizure of the Pueblo… may be a way of testing the readiness of the United States, embroiled as it is in Vietnam, to resist a broadened North Korean offensive,” or perhaps the attack was a way “to divert both the United States and South Korea from the Vietnam effort?” Had the Russians and the Chinese put them up to it? The Russians, after all, stood to gain a “great deal from capture and the study of the Pueblo’s electronic equipment.” There was little doubt in Washington that the attack on the Pueblo was part of a coordinated action linked to the broader context of the cold war and Soviet ambitions. The most likely explanation was that it had been prompted by the Soviet Union “to increase pressure on Washington to move to the negotiating table in Vietnam.” In his statement to the nation on January 26, President Johnson related the crisis to the “campaign of violence” against South Korean and American troops near the DMZ over the previous fifteen months. Johnson suggested that the attack on the Pueblo “may also be an attempt by the Communists to divert South Korean and United States military resources which together are resisting the aggression in Vietnam.” Although he did not mention the Soviet Union directly, it was clear that he believed that a conscious effort had been made to open up a second front in Asia. “The attempts to divert American efforts in Vietnam would not succeed,” he declared. “We have taken and are taking precautionary military measures [that] do not involve a reduction in any way of our forces in Vietnam.”56

Contrary to his assessment of Soviet and North Korean intentions, however, the war in Vietnam was not foremost on Kim Il Sung’s mind when the Pueblo was seized. Rather, it was the failed Blue House raid two days earlier that preoccupied him. Kim had sent commandos to South Korea in January 1968 with an order to assassinate Park Chung Hee. The attempt was a shortcut measure to “liberate” South Korea. Kim had hoped that the assassination would create the necessary political instability in the South to provide an opportunity for pro-North “revolutionary forces” there to usurp power, thus leading to reunification under his rule.57 Ironically, the operation failed through the commandos’ uncharacteristic humanitarian action. A day out from reaching their target, they had been hiding during daylight in the woods when four South Korean woodcutters discovered them. The standing procedure in such a case would have been to kill the witnesses, but after some intense discussion the commandos let the woodcutters go, with a firm warning not to report their discovery to the security forces.

The North Koreans would later come to regret their decision. Immediately after being released, the woodcutters went straight to the police. A massive manhunt was launched. The thirty-one commandos were nearly on the doorsteps of the Blue House when they were found. In the ensuing firefight and pursuit, all the commandos were killed except one, who was later captured. Sixty-eight ROK soldiers, policemen, and civilians and three American soldiers were killed in the hunt for the would-be assassins. Kim’s gamble had backfired, as huge anti–North Korean demonstrations were mounted in Seoul and a wave of anticommunist hysteria swept through the country. On January 30, a hundred thousand students in Seoul braved a nipping cold day to stage a protest against the North Korean regime. The rally included the appearance of “women whose sons had been killed by the Communists and several South Korean veterans of the war in Vietnam who went to the platform and ceremonially nicked their forefingers to write anti-Communist slogans in blood.” At the same time, a ten-foot straw effigy of Kim Il Sung was burned.58 To make matters worse, the surviving North Korean commando, Kim Sinjo, promptly confessed, provided details of the operation, and repented.59 That same day, thousands of students, parents, and teachers from Poin Technical High School and Kangwŏn Middle School in Kangwŏn province held anticommunist rallies to “denounce the barbarous armed provocations of North Korea” and burned an effigy of Kim Il Sung.60 The Kangwŏn ilbo summed up the defiant mood: “Although the Blue House raid and the Pueblo incident were indeed worrisome, we should not shake in fear for this is exactly what North Korea wants.” Instead, the paper proclaimed confidence in the people’s patriotic spirit: “As we saw with the Blue House raid, our people are thoroughly armed with anti-communism.”61 The Czech embassy in P’yŏngyang reported with a sense of awe how the South Korean government immediately capitalized on the spontaneous anti–North Korea demonstrations, even by leftist laborers, students, and intellectuals, to achieve its main objective: “to turn public attention from criticizing the government, army and police to a more acceptable matter—against the DPRK, which was a complete success.”62

Seoul high school students carry a placard depicting the captured USS Pueblo that says, “Return the Pueblo now!” The rally was attended by more than a hundred thousand people, with demonstrators burning an effigy of Kim Il Sung. (AP PHOTOS)

The failure of the Blue House raid had profound political implications for Kim. The vehement reaction against the raid demonstrated quite clearly that South Koreans had no desire to be “liberated” by the North. Moreover, the myth of a South Korean revolutionary force ready and willing to topple the Park regime and unify the peninsula under Kim’s leadership was shattered. It was the second time that Kim had severely miscalculated South Korea’s reaction to a North Korean probe.63 Mortified by the public criticism, Kim responded by blaming the entire affair on South Korean partisans. Less than forty-eight hours later, the Pueblo was seized.

The seizure of the Pueblo was done without prior knowledge of the Soviet leadership, contrary to White House assumptions. On January 24, North Korean Deputy Foreign Minister Kim Chae-bong simply announced to a group of stunned “fraternal” ambassadors in P’yŏngyang that an American intelligence ship had been captured. Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin was furious. He later complained that the Soviet Union “learned about [the details of] the Pueblo affair only from the press.”64 He was also uncertain about North Korean intentions, but assumed that the seizure was simply a pretext to divert attention from the failed operation in South Korea.65

Whether the Pueblo had actually trespassed into North Korean waters, as the North Koreans claimed, was viewed as largely irrelevant. American intelligence ships freely operated “near Soviet military bases and the Soviets freely monitored US communications off the American shores.” In the April 1968 Soviet Communist Party plenum, General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, who succeeded Khrushchev after the latter’s ouster in 1964, stated that the Pueblo’s seizure was “unusually harsh” by international standards.66 Rather, the bigger issue for the Soviet leader was whether North Korean “adventurism” would lead to war with the United States. Shortly after the Pueblo’s seizure, Brezhnev expressed concern that although “comrade Kim Il Sung assured [us] that the [North Korean] friends did not intend to solve the problem of uniting North and South Koreas by military means, and in this connection [did not intend] to unleash a war with the Americans … several indications appeared recently that, seemingly, suggested that the leaders of the DPRK have begun to take a more militant road.” He was worried that “the North Koreans did not appear to show any inclination toward settling the incident.” More alarming still, “DPRK propaganda took on a fairly militant character.” The North Korean people are told that “war could begin any day.” Brezhnev also noted that the country was on “full mobilization” and that “life, especially in the cities was changed in a military fashion.” In addition, “an evacuation of the population, administrative institutions, industries, and factories of Pyongyang” had already begun.67

Provoking the United States into a war could have been a primary motive behind the seizure. On January 31, Kim wrote to Kosygin expressing his confidence that the Soviets would come to his aid in the event of a war. “Johnson’s clique could at any time engage in a military adventure in Korea,” he wrote. “The policy of the American imperialists is a rude challenge to the DPRK, and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, who are bound together by allied relations according to the treaty of friendship, co-operation and mutual help between the DPRK and the USSR; [it is] a serious threat to the security of all socialist countries and to peace in the entire world.” He concluded that “in case of the creation of a state of war in Korea as a result of a military attack by the American imperialists, the Soviet government and the fraternal Soviet people will fight together with us against the aggressors,” and they “should provide us without delay with military and other aid and support, to mobilize all means available.”68

This brazen attempt to co-opt the Soviet Union into a war with the United States greatly alarmed Brezhnev, who decided that the time had finally come to put Kim Il Sung in his place. “To bind the Soviet Union somehow, using the existence of the treaty between the USSR and the DPRK [as a pretext] to involve us in supporting such plans of the Korean friend about which we knew nothing” was intolerable.69 On February 26, Brezhnev told North Korean Deputy Premier and Defense Minister Kim Ch’ang-bong, who had come to Moscow instead of Kim Il Sung at Brezhnev’s request, that the Soviets would not support a war. “We still base ourselves on the assumption that the Korean comrades maintain a course of peaceful unification of Korea, for we are not aware of [any] changes [to this course],” he told Kim Ch’ang-bong. Moreover, although “we indeed have a treaty, we would like to stress that it has a defensive character and is an instrument of defending the peace loving position of North Korea.” He asked North Korea to settle the Pueblo incident and the return of the crew “by political means without much delay.” Kim Il Sung was forced to acquiesce and soon sent assurances that he was pursuing a political solution, although he confessed it could be protracted. Kim had backed away from war.70 Still, Kosygin was concerned that the Soviets were getting their information on the Pueblo talks only through the open press and were “not aware of the considerations and plans of the DPRK government with regard to further development of events.” Kosygin ended with a promising incentive: “We do not have secrets from you, and we tell you everything frankly.” If the North Koreans are cooperative, the Soviets would do their best “to relieve the economic difficulties” caused by a decreased flow of goods from China.71 Brezhnev was less conciliatory, warning the North Koreans that “the DRPK could lose serious political gain obtained at the early stages of this incident.”72

China’s attitude toward the situation is less clear. At the time, China was embroiled in the Cultural Revolution. Since 1965, Sino–North Korean relations had been severely strained because of Kim’s entirely pragmatic decision to side with the Soviets in the Sino-Soviet dispute. The fall of Khrushchev from power in October 1964 had temporarily thawed relations between China and the Soviet Union, but when Khrushchev’s successor, Leonid Brezhnev, sent Premier Kosygin to China to smooth over differences, disputes concerning joint action and aid to North Vietnam renewed tensions. Beijing, only reluctantly and with constant delays, allowed railway transit of Soviet aid to North Vietnam through Chinese territory.73 Kim repeated Soviet and North Vietnamese complaints that China was blocking Soviet shipments. It was only natural that North Korea sided with the wealthier Soviet “revisionists” as opposed to the poorer Chinese “dogmatists.” On January 21, 1967, North Korea issued its first official statement criticizing Chinese policies. It branded Mao’s dictatorship as more disastrous to international communism than Khrushchev’s revisionism. The Chinese responded by branding the DPRK as another revisionist regime. That year, clashes between Chinese Red Guards and ethnic Koreans in China’s Northeast became particularly grisly and ominous when Korean bodies were displayed “on a freight train traveling from the Chinese border town of Sinŭiju into the DRPK, along with graffiti such as ‘Look, this will be also your fate, you tiny revisionists!’” Open retaliation against the Chinese provocations was too risky. Instead Kim strengthened his personality cult and his brand of communism in opposition to the Cultural Revolution. He told a Soviet visitor on May 31, 1968, that North Korea’s relationship with China was “at a complete standstill.”74 Kim knew he could not count on Chinese support in a war against the Americans.

The problem Kim faced was how to defuse the Pueblo crisis without losing face with his own people. He knew that simply releasing the crew without an official apology from the United States would severely weaken his position and power by undermining his reputation as a fearsome revolutionary fighter who had the courage to stand up to foreign powers. It might even lead to his overthrow. Since the mid-1950s, North Korean domestic propaganda had dwelt increasingly on the virtues of national self-determination by touting North Korea’s economic success made “without foreign assistance.” Kim’s talk of self-reliance, which he contrasted to the “lackey” regime in the South, meant that resolving the crisis without an official American apology—in effect, admitting he had backed down to U.S. pressure—would be quite impossible.

The Soviets understood the North Korean leader’s dilemma. Over the following months, while Kosygin worked quietly to keep North Korean belligerence from turning into a military confrontation, he also pressured the Americans to yield to North Korean demands for an official apology, which he conveyed to Llewellyn Thompson, U.S. ambassador to Moscow and a longtime Russia hand. Thompson praised Kosygin for acting with “a distinct tone of restraint” in trying to negotiate an end to the crisis, citing his willingness to be a mediator between the two countries.75 “There were enough conflicts in the world already and there was no need to have a new one,” Kosygin told Thompson.76 Thompson was convinced that the Soviets did not want war.

The result of the delicate triangular finessing and balancing of North Korean, Soviet, and American interests was a long and drawn-out negotiation. North Korea stood its ground not to back away from demanding official admission of “hostile acts and intrusion” into North Korean territory, a “proper apology” and guarantee “against future similar incidents” as a condition for the release of the crew. The Americans balked: “We know, and can prove, that at least some of the documents which they [the North Koreans] have given us are falsified,” Dean Rusk told President Johnson. “I firmly believe that we should not admit incursions which we are reasonably certain did not occur.”77 Johnson agreed. He desperately wanted to secure the release of the crew, but without forsaking America’s honor and credibility. The impasse was on.

The ordeal for the Pueblo’s crew, a complement of eighty-three men, contained its share of drama, violence, surprise, and humor. Captain Lloyd “Pete” Bucher, the commander of the ship, did not know what to expect when they were taken to P’yŏngyang. Some of the men had been injured, and one man, Duane Hodges, was killed in a brief firefight. Bucher, battered and beaten, wondered in his prison cell whether he and his men could withstand the harsh interrogations that would no doubt follow. The ship’s intelligence value was staggering. It was full of the most sensitive electronics and classified documents. The men had tried to destroy them, but there was simply too much and too little time. The crew also included specialists who had intimate knowledge of intelligence capabilities and operations. Their personnel files, on the ship and captured, could tell exactly what their specializations were and where they had served.78

Bucher was soon taken to the interrogation room. He was relieved when he was not asked about the Pueblo ship’s equipment, documents, or crew. Instead, the excitable Korean colonel, whom Bucher later nicknamed “Super-C” (for Super Colonel), handed him a confession to sign. “I took advantage of the opportunity to glance through it, catching among the rest of stilted English-Communist composition some specific reference to my admitted association with the CIA in provoking North Korea into a new war. And to promises of great rewards to myself and my family if I succeeded in this infamous mission.” Bucher refused to sign and braced himself for a “painful pummeling.”79 Over the next few days, Bucher “puzzled a great deal about the nature of the questions the interrogators had concentrated on so far, wondering why they had asked so little oriented towards obtaining technical information, military intelligence. Instead they seemed completely hung up on a propaganda line for purely political purposes when dealing with me.”80 Other crew members were similarly mystified. Bucher’s executive officer, Lieutenant Edward R. Murphy, wondered whether the North Koreans had really “comprehended the importance of their capture. Their questions indicated little interest in the equipment aboard.” He observed that they had shown “only undisguised amazement that such a small ship had such a large crew.”81 They seemed to be concerned only with using the Pueblo and its crew for propaganda purposes rather than extracting intelligence. “We seemed to be entirely in the custody of propaganda, not intelligence specialists,” observed Bucher. “It became obvious to me that the Korean communists had not the slightest intention of going after information of real intelligence value from us.”82

Initially, Bucher thought the North Koreans were biding their time until Soviet interrogators arrived. They never did. Instead, the North Koreans just repeated their demand for signed confessions and letters of confession and apology to the Korean people, family members, newspaper and magazine editors, political leaders, and the White House. Eventually, Bucher decided to comply. The strain had become too much to bear when the stakes of compliance seemed so low. He was sure that no one in the United States would believe the crew’s worthless “confessions.” Bucher considered breaking the Code of Conduct, but he did not believe that endangering the life of his men was worth refusing to sign worthless pieces of propaganda. He was not betraying any secrets, after all. He encouraged his men to include in their confessions and letters verbal subterfuges, especially in personal letters to family members, to indicate that they had been written under duress. The subterfuges included mentioning nonexistent relatives, using outlandish or fictitious names, and referencing nonexistent possessions. For example, Bucher concluded his second letter to his wife, Rose, by telling her to send his greeting to his relative “Cythyssa Krocasheidt.”83 When Super-C requested names of influential leaders who “would work on your government for an apology,” the men suggested writing to “labor leader Jimmy Hoffa and the Reverend Dr. Hugh Hefner.”84 Visual subterfuge was also used. A group picture inserted in a letter to one family member showed some of the men making the “Hawaiian hand gesture” by extending the middle finger. The prisoners had convinced their captors that the gesture was meant as a good luck sign. The trick worked until one day a family member, puzzled by the picture, released it to the local paper, which was then picked up by the national press. The North Koreans were furious to discover its true meaning.85

Meanwhile, the men continued to wonder what the North Koreans hoped to accomplish. Bucher and his men were forced to listen to lectures, lasting hours, about “America’s imperialistic sins,” the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the CIA, South Korean traitors, the miseries caused by the United States, and so on. It seemed like an attempt at brainwashing, the sort they had heard about from the Korean War, but it was not particularly intense. Sometimes they were asked questions that any ordinary map or encyclopedia could have easily answered. Questions pertaining to the Pueblo were even more baffling. The North Koreans wanted to know, for example, about all the supplies that Lieutenant Stephen Harris had ordered for the ship, including the exact amounts and quantities. Harris made them up, and his interrogator “wrote down faithfully every nonsensical figure he gave them.”86 But what they seemed most intensely curious about was American society and social mores, especially sex. James Layton recollected, “If they had questioned the Americans as closely on military matters as they did on American women, the entire U.S. Navy’s communications system would have been in jeopardy.”87

The North Koreans worked hard to keep the prisoners the focus of domestic attention, staging public appearances solely for popular consumption.88 There was apparently no interest in appealing to the outside world, including Soviet and Chinese audiences. The prisoners appeared in film and television productions that would be seen only by North Koreans. They were taken on public excursions, a concert, a theater production, and even a circus performance, where they were more part of the show for the North Korean public than of the audience. They were featured in “press-conferences” and wrote regularly for the Nodong sinmun, the official NKWP newspaper. Bucher and his men did their best to undermine the propaganda. In one joint letter to the Korean people, entitled “Gratitude to the People of Korea for Our Humane Treatment,” Bucher inserted this dig at their North Korean captors:

We, who have rotated on the fickle finger of fate for so long … we of the Pueblo are sincerely grateful for the humane treatment we have received at the hands of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and we not only desire to paean the Korean People’s Army, but also to paean the Government and the people of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.89

It was only in the last month of their captivity, when the North Koreans caught on to the true meaning of the “Hawaiian hand gesture,” that they punished the prisoners mercilessly. By then, however, the game was getting old. After nearly one year in captivity, the prisoners were losing their effectiveness as a propaganda tool. “The North Koreans had exhausted their propaganda efforts,” Lieutenant Murphy later explained. “We were no longer an asset to them.”90 The Americans were also becoming increasingly impatient. Something had to be done.

The solution to the crisis came from an unlikely source. James Leonard, the country director for Korea in the State Department, had discussed the frustrating situation with his wife, Eleanor. Every American proposal had been rejected, and North Korea would not back down on their demand for the “Three A” solution (“admit, apologize, assure”). Eleanor suggested that “if you really make it clear beforehand that your signature is on a false document, well, then, you remove the deception.”91 Leonard thought it worth a consideration and took the proposal to Rusk, who in turn discussed it with President Johnson. They could not see how it could possibly work, but thought it was worth a try. The proposal was made on December 15, and two days later it was accepted.92

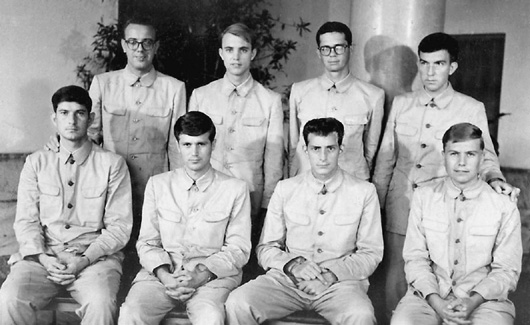

Pueblo crew showing the “Hawaiian hand gesture” of good luck. (AP PHOTOS, KCNA)

The Americans were stunned. In effect, the Americans had agreed to sign a Korean-drafted document of apology “for grave acts of espionage” after branding it an outright lie. Moreover, they had repudiated the document with the full and prior knowledge of the North Koreans, who “had agreed beforehand that the United States would proclaim their document false and would sign it to free the crew and only to free the crew.”93 Rusk called the resolution bizarre: “It is as though a kidnapper kidnaps your child and asks for fifty thousand dollars ransom. You give him a check for fifty thousand dollars and you tell him at the time that you’ve stopped payment on the check, and then he delivers your child to you.”94 General Charles Bonesteel, commander of U.S. forces in Korea, noted, “It is difficult to explain its rationality. I don’t know whether they’ve gotten bored with the crew, or possibly thought they had diminishing value as propaganda there.”95 Walt Rostow, who served as Johnson’s special assistant for national security affairs, thought the North Koreans were simply “nuts.”96

But the “nutty” resolution made perfect sense within the context of North Korea’s domestic politics. It satisfied Kim Il Sung’s one and only condition: a signature on a piece of paper that proved to his isolated domestic audience that he was a great revolutionary fighter who was both feared and respected by the United States. The signed confession was also important in “proving” that, in contrast to the southern “lackey regime,” North Korea was strong and brave enough to force the world’s greatest military power to bow to its demands. Since the confession mattered only to his own people, who had no access to other sources of information, Kim did not care whether it was discredited by the rest of the world. In the ongoing legitimacy wars with South Korea, this was all that mattered.

On December 23, 1968, as snow fell on the barren hills surrounding P’anmunjom, the remains of Fireman Apprentice Duane Hodges were taken over the Bridge of No Return. Bucher followed, and then the rest of the crew. As the men were repatriated where the armistice had been signed fifteen years earlier, North Korean radio announced the nation’s triumph. The American apology represented the “ignominious defeat of the United States imperialist aggressors and constitutes another great victory of the Korean people who have crushed the myth of the mightiness of United States imperialism to smithereens.” It was also announced that the ship would not be returned, but “confiscated.”97 Today, the Pueblo currently resides on the banks of Taedong River in P’yŏngyang, where it has become a favorite tourist destination.