LIKE A LONE MAGNOLIA BLOSSOM BENDING TO THE WIND

Under heavy silence

Of a house in mourning

Only the cry of cicadas

Maam, maam, maam

Seem to long for you who is now gone

Under the August sun

The Indian Lilacs turn crimson

As if trying to heal the wounds of the mind

My wife has departed alone

Only I am left

Like a lone Magnolia blossom bending to the wind

Where can I appeal

The sadness of a broken heart

—PARK CHUNG HEE, August 20, 1974,

composed the day after his wife’s state funeral1

Park Chung Hee awoke every morning to the picture of his wife, Yuk Yŏng-su. On a table under her portrait rested two vases of fresh chrysanthemums and next to them, in a wooden box, was a book about the late First Lady written by the celebrated poet Pak Mok-wŏl. Park missed her dreadfully. In the years after her death, Park had been under a great deal of strain. After a long period of rapid growth, South Korea was experiencing rising political unrest aggravated by an economy that was now stagnant, owing to the 1973 oil crisis and a worldwide recession. Carter’s criticism of the regime’s human rights record had also emboldened Park’s critics. Park’s aides were concerned that he was becoming emotionally unstable.

The tragedy took place at the National Theatre on August 15, 1974. Park was giving a speech to commemorate the twenty-ninth anniversary of the nation’s liberation from Japan when shots rang out. Yuk Yŏng-su slumped to the floor. The bullet, fired by a Japanese North Korean assassin, Moon Se-kwang, was meant for Park. Many believed that Park was unable to recover from the shock, and his leadership suffered as a consequence. “Park’s power and handling of power changed when she died,” observed his biographer Cho Kap-je. “He appeared to become more and more a shell of a man lacking his previous substance. His ability to balance his personality and the use of power had diminished considerably in the last years of his life.”2

By the time of his death, Park was increasingly isolated. In the 1960s he had been able to travel freely, interacting with people without too much restraint, but since the assassination of his wife, his movements had become severely restricted, depriving him of human contact. Yuk also had had a humanizing influence on him, and without her he felt lost, vulnerable, and insecure. In Park’s bedroom side drawer, he kept two rifles. “The man who had gained power by the gun,” observed Cho, “felt that someday the gun would be turned on him.”3

Park Chung Hee with his wife, Yuk Yŏng-su, celebrating Park’s forty-ninth birthday, on September 30, 1966. Yuk was Park’s second wife; the two had married on December 12, 1950, in the midst of the most harrowing phase of the Korean War. Yuk’s father was against the match, but Yuk married Park anyway without her father’s blessing or approval. (SAEMAŬL UNDONG CENTRAL TRAINING INSTITUTE)

That day came sooner than anyone had expected. On the evening of October 26, 1979, while dining in the company of his associates, Kim Chae-kyu, the chief of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency (KCIA), and Ch’a Chi-ch’ŏl, Park’s powerful head of Blue House security, Park was shot to death. His demise came not from the hands of a North Korean assassin, but from Kim, an original member of the revolutionary group that took power in May 1961 and one of Park’s closest colleagues and advisors. During the investigation and trial, Kim espoused the view that the violent demonstrations and political unrest wracking the nation were an indication of growing public dissatisfaction with Park’s rule, and that he believed the time was ripe for a democratic revolution.

However, the real motive for the assassination was something more prosaically personal. Friction between Kim and Park was exacerbated by Kim’s growing resentment of Park’s body guard, Ch’a Chi-ch’ŏl, who became more powerful and influential after he became the Blue House security chief in 1974 in the wake of Yuk Yŏng-su’s death. “That night, it appeared that Kim Chae-kyu was only thinking of killing the president and he had no plan of action for what to do afterwards,” wrote Cho Kap-je. “The fact that he had no idea about which command center was most effective for carrying out a coup d’etat shows that the assassination was not premeditated and was a more spontaneous decision.”4 Kim had shot Ch’a first before turning his gun on Park, allegedly saying, “Sir! The reason why the political situation is a mess is because you are served by this worm of a man [Ch’a]!” Subsequent investigations supported the conclusion that Park’s murder was a crime of passion and not the result of a conspiracy.5

Park’s assassination opened a new era of uncertainty in South Korean politics. By the time of his death, vocal critics of the Park regime were demanding greater freedom and democracy. At the same time, the reality of the unending war marked by frequent and violent military confrontations along the DMZ and costly terrorist actions instigated by Kim Il Sung’s regime made the possibility of a transition to democracy in the South very unlikely.6

For a time after Park’s death, it looked as if Kim Il Sung’s cherished dream of fomenting revolution in the South might happen. Taking advantage of the atmosphere of uncertainty following the events of October 26, opposition politicians and student activists began to loudly voice their demands to lift martial law and hold direct presidential elections. The large-scale release of dissidents in July that Park had agreed to during Carter’s visit had emboldened Park’s critics, and they demanded immediate changes to the Yusin constitution. Meanwhile, government and military leaders argued that the Yusin charter must remain in effect until the late president’s successor could be chosen, to ensure stability and security. Acting President Ch’oe Kyu-ha, a “soft-spoken” former diplomat and Park’s prime minister, was formally elected interim president on December 6. But Ch’oe had no independent political backing, and the real power lay with the military.

That power asserted itself on the night of December 12, when Gen. Chŏn Tu-hwan (Chun Doo Hwan), who had taken control of South Korea’s intelligence apparatus since Park’s assassination, staged a coup. Ambassador Gleysteen and the senior U.S. commander in Korea, Gen. John Wickham, stood by essentially as spectators, having little leverage over the unfolding events. “The era of America’s paternal influence over the ROK had passed,” Wickham concluded. “Since the United States had significantly reduced its military deployment … and had recently threatened to withdraw even those forces, ROK leaders doubted the reliability and continuity of America’s commitment.” Although President Carter had spent his entire presidency pressuring South Korea to liberalize and reduce the influence of the military, in the end he got exactly the opposite.7 The events of December 12 put an end to any hope for the emergence of democratic and civilian rule. The South Korean people were outraged.

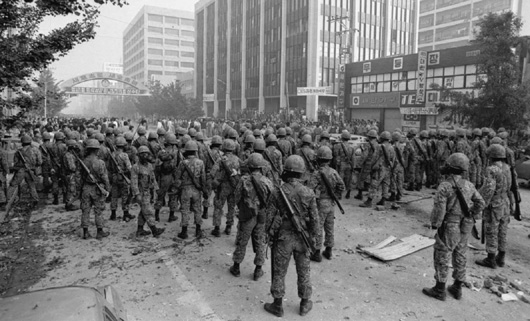

Chŏn had at first blamed the unrest on a “minority” of student radicals, professors, and intellectuals. However, with daily protests continuing unabated for months on end, he suddenly changed his tune and on May 13 played the North Korea card. Widespread arrests of students and oppositional leaders followed, and martial law was declared on May 17. The citizens of Kwangju rose up in anger when they received news that Kim Dae-jung, who had almost defeated Park in the 1972 presidential elections, was arrested in the early morning hours of May 18. Kwangju was the capital city of Kim’s home region, the South Chŏlla province in southwestern Korea, and Kim was their local hero. This region had been neglected during the economic boom of the 1960s and 1970s because Park had concentrated on developing the southeastern region of Korea, where he was born. Resentment over regional favoritism fueled the anger evoked by the arrest of Kwangju’s favorite son. Its citizens responded by seizing weapons from local police, turning the city into a fortress, while demanding the release of Kim and the restoration of democracy. Chŏn responded by ordering the city surrounded by army units. He then unleashed them to retake control. The outcome of the battle between well-armed and organized regular soldiers, many with combat experience in Vietnam, against a hastily assembled citizen militia armed with only a hodge-podge collection of light weapons was predictable.

South Korean soldiers on guard in downtown Kwangju, May 23, 1980. The Kwangju uprising was a pivotal moment in South Korea’s struggle for democracy. Swept up by a tide of demonstrations following the death of Park Chung Hee and the military coup that brought Chŏn Tu-hwan to power, the brutality of the new regime’s response outraged many Korean citizens. The Kwangju Uprising also tainted South Koreans’ view of the United States due to Washington’s alleged role in the suppression of the uprising, thus giving rise to fervent anti-Americanism, especially among students. While student dissidents began questioning the U.S. role in Korean affairs, they also began challenging their nation’s traditional hostility toward North Korea. (AP PHOTOS)

The city was retaken on May 27. Official government estimates of the number of civilians killed ranged from 170 to 240, but the actual number was likely higher. The brutal put down and killings fueled an intense national opposition to the Chŏn regime, especially from students. Rumors of U.S. complicity also fanned anti-American sentiment.8 But it was the magnitude of state violence and the complete devastation of democratic forces and processes after the Kwangju uprising that drove many South Korean dissidents and intellectuals to search for the origins of their nation’s predicament. While Kim Il Sung continued his efforts to disrupt South Korean society with a new emphasis on terrorism, these students looked to North Korea for answers to their nation’s problems.

One way students did this was by openly embracing North Korea’s version of the ongoing war between the two Koreas. Accepting Kim Il Sung’s view of the conflict as that between Korean revolutionary nationalists in the North and American “imperialists” and their “lackey” South Koreans meant that South Korea was seen as a “puppet” creation of the Americans. Students’ embrace of this North Korean line also recycled Kim’s chuch’e ideology (chuch’eron), which stressed North Korea’s self-reliance and active resistance to foreign powers.9 By the mid-1980s, chuch’eron had gained widespread influence among student dissidents and intellectuals.

This influence was manifested in two important ways. First, students began to directly challenge and subvert decades of cold war rhetoric that portrayed North Korea as the enemy of the South. The officially accepted relationship between friend and foe that had been part of the established South Korean line since the Korean War was turned upside down in chuch’eron. Instead, the real enemy of the people was the United States, not North Korea. These dissidents saw the U.S. decision to divide, occupy, and establish a military regime in southern Korea as a direct expression of imperialist ambitions in the Korean peninsula. They also questioned the very legitimacy of the South Korean state by playing up Kim Il Sung’s resistance to the UN foreign-sponsored elections in 1948, on which the ROK claimed its legal basis. Moreover, whereas state-sponsored histories saw North Korea’s menace solely in political and ideological terms, students argued that the United States, the “new” enemy, posed a threat that was much more radical and fundamental. The American capitalist culture represented an invasive force that threatened to undermine the very core of Korean national identity. The decadent individualism of the West, which these dissidents associated with consumerism, sexual promiscuity, and crime, presented external threats that required a nationalist strategy to combat.

Second, the students’ rejection of the established South Korean view of North Korea as the main “enemy” forced them to come up with new ways of depicting the North-South relationship. Interestingly, they did this by drawing on a traditional canon of Confucian morality tales about women’s steadfast loyalty during periods of loss and forced separation from their husbands. The eighteenth-century Tale of Ch’unhyang, Korea’s most renowned love story, was especially influential. It concerns the love between the son of an upper-class family named Yi Myong-nyŏng and the daughter of a socially despised kiseang (female entertainer) named Ch’unhyang. After their engagement, Yi is called to duty in the capital far away from Ch’unhyang. Shortly thereafter, Ch’unhyang is sent to prison when she refuses the advances of the evil local governor. Finally, her husband returns, rescues her, and punishes the evil governor, and they live happily ever after. Every Korean, North or South, is familiar with this tale. Indeed, it has been the subject of numerous books, dramatic performances, movies, and cartoons in both Koreas.10

Students thus used the Ch’unhyang narrative in their portrayal of the division. As an exemplary model of Korean virtues, unwavering, faithful, and determined to undergo whatever tribulations required to resist the forces of evil, the loyal Ch’unhyang came to represent South Korea. Ch’unhyang remains true to her husband (North Korea) by defiantly resisting political authority and not succumbing to the advances of the lascivious evil governor (the United States). Implicit references to the Ch’unhyang story appeared repeatedly in student illustrations and pamphlets. Images of two lovers about to fall into each other’s embrace or of a happy couple triumphantly running across the DMZ revealed the connection between marital union and a reunified nation. Indeed, to think of North and South Korea as lovers, struggling to overcome the division of the peninsula, challenged decades of cold war rhetoric.

If marriage represented the unification of the two Koreas and the end of the war, then the division of the peninsula was often compared to rape. Rape signaled the breakdown of the marital bond and thus symbolically came to stand for the nation at war with itself. During colonial times, rape was often used to evoke Korea’s experience under Japanese colonialism. It was also rooted in the real-life experiences of thousands of Korean women who were forcibly and systematically recruited by the Japanese government to serve as prostitutes (euphemistically referred to as “comfort woman”) for Japanese soldiers during World War II. In both colonialism and the division, the image of the violated woman carried with it the values of purity against filth, and of chastity against foreign contamination. A famous poem by the “resistance” poet Kim Nam-ju, “Pulgamjŭng” (1988), shows how prostitution, rape, and violence become interrelated themes in their symbolism for the division:

“The Road to Unification,” illustration of a man and woman embracing in the shape of the Korean peninsula, used in a Seoul National University student pamphlet, April 1989. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

My elder sister

Is our liberated country’s lady of the night.

To borrow one highly venomous tongue,

She is a widely gaped vulva like a

Chestnut burr under the boots of the U.S. Eighth Army.

My little sister is our modernized country’s new woman.

To borrow an expression of a common boy,

She is a widely open tourist vulva under the Japanese yen.

How deep did we lapse by rotting.

Not awakening no matter how much [we are shaken].

Not feeling no matter how much [we are pinched].

Ah, my half-piece country,

After 36 years of broken waist, when will you open your eyes from

Your long, long humiliating sleep…11

The title “Pulgamjŭng,” meaning frigidity, refers to a woman’s guilt or fear of becoming pregnant or contracting a venereal disease. Rape constituted not only a threat to the marital bond but also a crisis of maternity and female reproduction. For many student dissidents, the danger of Western, and specifically American, cultural contamination was perceived as a threat to the integrity and purity of the Korean nation. To defend the nation’s inner “core,” Korean women needed to resist the advances of the lascivious foreign male. The reality of American military presence in South Korea exacerbated this perceived crisis. The murder of a Korean prostitute by an American soldier in November 1992 provoked a national outrage igniting large demonstrations in Seoul. Students demonstrated for a full week while even taxi drivers refused to serve American soldiers. The accidental death of two schoolgirls caused by two American soldiers ten years later, on June 13, 2002, caused a similar wave of anti-Americanism that No Mu-hyŏn (Roh Mu-hyun) rode to the presidency in 2003.12

The focus on sweeping South Korea clean of America’s “putrefying influence” was, of course, a central theme of Kim Il Sung’s chuch’e ideology. In contrast to North Korea, which was deemed clean and pure and had established itself “without reliance on foreigners,” the South was deemed polluted in every way. The description of South Korea in the North Korean novel Encounter (Mannam) was standard North Korean propaganda: “[South Korea was] the flashiest of American colonies … but look under the silk encasing and you see the body of what has degenerated to a foul whore of America.” South Korea has been “covered in bruises from where it has been kicked black and blue by the American soldiers’ boot.”13 Similar preoccupations with purity and pollution also appeared in South Korea’s dissident rhetoric, combining calls for the two Koreas’ “national rebirth” with the hope for deliverance from the war and division perpetuated by the United States. This rallying cry for a “liberated” and reunified Korea during a 1989 student demonstration in Seoul was typical of student hyperbole during this period:

Youth! You who vigorously strike the bell of freedom at dawn, stomp out the dark shadows of the Stars and Stripes with bloody cries, and with longing for the sun-shining Mt. Paektu, work for the independence and reunification of this land. Only then will spring arrive joyously. Let us finish together the incomplete revolution so that we can live in a better world.14

The idea that students were struggling toward spring merely recycled North Korean propaganda about the “unfinished” revolution. Korea’s spring meant a return to the nation’s pristine origins before the peninsula was divided and before the South went from a Japanese colony to an American one. Appropriating Kim Il Sung’s propaganda, student dissidents thus offered a vision of South Korea’s true liberation from all foreign powers by embracing the chuch’e idea as their own.

Hours before taking to the streets to do battle with riot policemen, usually at the entrance of the university gate, students put on musical performances, dances, and historical dramas about key events in Korea’s modern history. On the occasion of the ninth anniversary of the Kwangju uprising, students at Chŏnnam University in Kwangju recounted those events in a musical performance. Kwangju, May 18, 1989. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

The naiveté of these fanciful musings aside, by focusing on the virtues of Koreaness versus foreignness, student dissidents had idealized the North Korean regime. North Korean officials were no doubt heartened by the spectacle of South Korean students hurling Molotov cocktails at riot policemen dressed in full battle gear on the streets of Seoul, for it reconfirmed the regime’s old propaganda line that the South Korean people were chafing under the yoke of American imperialism and longed to be liberated by their northern brethren. Even as late as the 1980s, Kim Il Sung had still not relinquished the dream of fermenting a nationalist revolution in the South.

In the legitimacy wars between North and South Korea, South Korean student dissidents had thus clearly sided with the North. In their embrace of Kim Il Sung’s chuch’e thought, which became de rigeur within the mainstream of the student movement during the 1980s, they also condemned the United States and the American-backed “puppet” regime in the South as the main enemy.

Although some of this revolutionary rhetoric later softened and became absorbed into mainstream South Korean society well into the turn of the twenty-first century, it would take P’yŏngyang’s economic collapse and the exposure of its nuclear ambitions to rid many South Koreans of their romantic illusions.15