Kim Chŏng-ŭn, front right, walks beside the hearse carrying the body of his late father, Kim Jong Il, during a funeral procession in P’yŏngyang on December 28, 2011. Behind Kim Chŏng-ŭn is Chang Sŭng-taek, Kim Jong Il’s brother-in-law. (AP/KCNA)

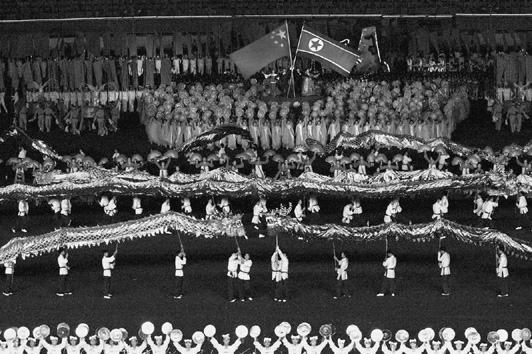

ON THE MORNING OF December 28, 2011, hundreds of thousands of North Koreans lined the snow-covered streets of P’yŏngyang to bid farewell to their Dear Leader, Kim Jong Il.1 The three-hour funeral event, which was broadcast live on North Korean television, showed wailing crowds of men and women as a tearful Kim Chŏng-ŭn, Kim’s youngest son and chosen successor, trudged through the snow alongside the black limousine that carried his father’s casket. The snowfall also gave the country’s state-run media fresh material with which to eulogize the Dear Leader since his unexpected death was announced on December 19: “The feathery snowfall reminds the Korean people of the snowy days when the leader was born in the secret camp of Mt. Paektu and of the great revolutionary career that he followed through the snowdrifts.” The reference to Mt. Paektu, the legendary site where Korea’s mythical founder, Tan’gun, had descended from the Heavens and the place where Kim Il Sung had waged his battles against the Japanese, provided a fitting symbol to mark the end of the dictator’s life. In his death, the snow imagery also showed the way forward to his rebirth: “The march in the new century of the Juche [Chuch’e] era,” went the joint 2012 New Year’s editorial, “is the continuation of the revolutionary march that started up on Mt. Paektu. Steadfast is the will of our service personnel and people to adorn our revolution, pioneered by Kim Il Sung and whose victory after victory they won following Kim Jong Il, with eternal victory following the leadership of Kim Jong Un [Kim Chŏng-ŭn].”2

Although the twenty-something Kim Chŏng-ŭn hardly seemed prepared to take over his father’s mantle, having just been introduced to the Korean people in 2010, North Korean officials quickly rallied around their new king. But more important to the future of North Korea was that Chinese leaders did too. Just one day after the announcement of Kim Jong Il’s death, China moved swiftly to assure its communist ally of its strong support amid the uncertain leadership transition. On December 20, President Hu Jintao visited North Korea’s embassy in Beijing to offer his condolences while Foreign Ministry spokesman Liu Weimin offered a crucial endorsement to “Comrade Kim Chŏng-ŭn,” calling on him to build a strong Communist country and realize permanent peace on the Korean peninsula.”3 At the same time, a number of PRC Central Committee members, including China’s number two, Premier Wen Jiabao, paid their respects to the deceased leader at the embassy. Wen’s remarks, in particular, reinforced the strong emphasis that China’s leaders have placed on ties with North Korea:

Comrade Kim Jong Il was the North Korean Worker’s Party and country’s great leader, and a close friend to the Chinese people. Since long ago, he developed the cooperative and friendly relations between China and North Korea, producing great achievements [in that area]. We believe that the Korean Worker’s Party under the leadership of Kim Jong Eun [Kim Chŏng-ŭn] the North Korean people will certainly pass through their grief, pushing forward to new successes in socialist construction. The Chinese side wants to take the same road as the Korean side, in order to further and consolidate and develop the traditional friendship and cooperation between the two countries, striving together.4

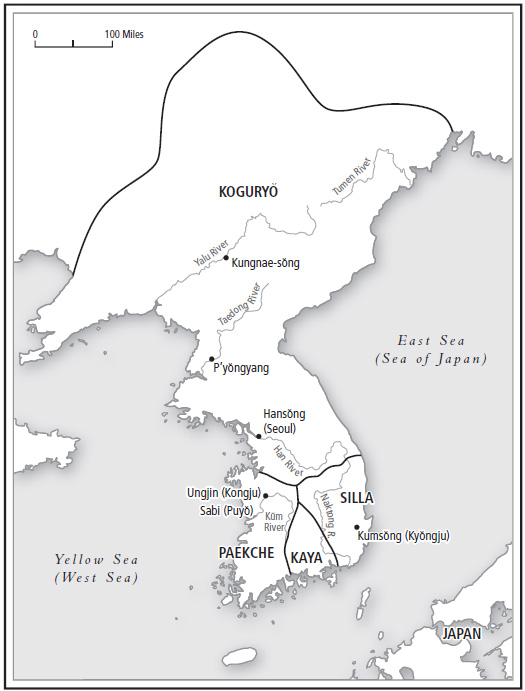

South Koreans have been concerned about China’s rise and growing influence in North Korea for some time. These concerns became clear in the summit meeting between former South Korean president No Mu-hyŏn and Premier Wen that was held on September 10, 2006, in Helsinki. They had come to attend the Asia-European Meeting forum in order to discuss pressing bilateral issues.5 Press reports of the meeting reveal that the two leaders spent a good part of their time discussing ancient history, specifically the history of the Koguryŏ/Gaogouli kingdom. Koguryŏ was one of the three ancient kingdoms of Korea, along with Paekche and Silla, which existed between the third millennium and the seventh millennium AD.6 At the height of its power in the fifth century, Koguryŏ encompassed a vast area in what is today Northeast China and North Korea. During his meeting with the Chinese premier, the South Korean president wanted to discuss recent reports by Chinese archeologists and historians who claimed that since Koguryŏ’s former territory now resides within the current borders of the PRC, its history should be considered part of “Chinese history.”7 Official press releases of the meeting later revealed that President No “had expressed his dissatisfaction with some conclusion of the Chinese archeological teams and the publication of a provincial research center dealing with events some two thousand years ago.”8

President No’s concern over China’s historical treatment of Koguryŏ began in 2002, following China’s launching of its ambitious Northeast Asia Project. The ostensible aim of the project was to “strengthen the association between China proper [all of China] and the northeast region,” which includes three provinces: Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning. But as the South Korean public soon learned, the Chinese government and scholars associated with the project appeared to be “conducting a systematic and comprehensive effort to distort the ancient history of Northeast Asia” by portraying Koguryŏ and the succeeding state of Parhae (Korean)/Bohai (Chinese) as Chinese, not Korean, kingdoms. In April 2004, the South Korean government lodged a formal protest following the appearance on the Chinese Foreign Ministry website that portrayed Koguryŏ as Chinese and removed references to Koguryŏ as being part of Korea’s Three Kingdom era.9 Beyond this bickering over history, however, the political ramifications of the dispute have been far-reaching. By claiming Koguryŏ as part of China’s ancient past, the South Koreans charge, the Chinese government was surreptitiously undermining the legitimacy and political authority of North Korea whose territory was once part of Koguryŏ.

Map of the Three Kingdoms of Korea (AD 300–600) (Kaya was not a kingdom, but a confederation of tribes). In AD 660 Silla conquered Paekche with the help of T’ang China, and eight years later, in 668, Silla and the T’ang subdued Koguryŏ. Turning on its ally, the T’ang then invaded Silla in 674, but Silla was able to finally drive the T’ang from the Korean peninsula in 676, thereby achieving the unification of the peninsula. However, most of Koguryŏ’s former territory in Northeast China was not included in Silla’s unification.

China’s treatment of Koguryŏ has not been all that different from the way it has treated other ancient tribes and states that are now part of the PRC.10 Knowing that the threat to the integrity of the Chinese nation has historically always come from internal challenges to its central authority, China launched an ambitious plan to exert control over its diverse ethnic population by promoting a common Chinese identity under the rubric of being a “multi-ethnic nation.”11 The link made between Koguryŏ and the Northeast provinces like Jilin, whose majority population is ethnic Korean, has clearly been a way to increase the notion of a Chinese identity among ethnic minorities.

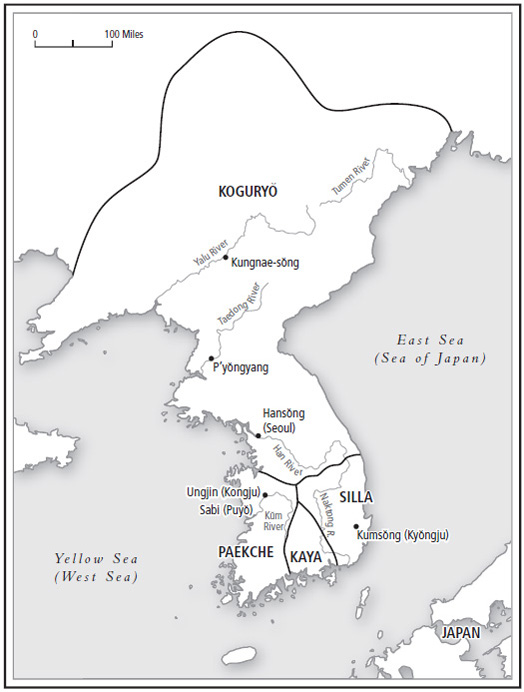

China’s Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning provinces and North Korea.

But the Northeast Asia Project clearly has another aim: to construct a unitary national history and identity in the Northeast intended to pave the way for the economic intervention and integration of North Korea. Indeed, it is not coincidental that China’s concern with Koguryŏ’s history began in earnest in 2004 when Premier Wen announced that the Chinese government would embark on an ambitious economic development project for the Northeast provinces. According to Chinese government sources, Chinese investment in North Korea in 2006 topped $135 million and bilateral trade reached $1.69 billion, “an increase of almost seven percent over the $1.58 billion in bilateral trade in 2005.”12 Trade imbalance and North Korea’s economic dependence also reached lopsided proportions, with imports from China of crude oil, petroleum, and synthetic textiles amounting to $2 billion while exports, consisting mainly of coal and iron ore, totalling just $750 million.13 These investments are similar to the contributions to the DPRK’s economy during the 1953–60 period, except that China now exerts far greater political leverage over the P’yŏngyang regime because North Korea now has no one to rely on but Beijing.

Despite China’s increasing involvement in North Korea, however, Chinese leaders realize that merely propping up the regime without fundamentally transforming its economy will not resolve China’s main security dilemma in the region: maintaining stability and peace on the Korean peninsula. Hence, China’s ambitious efforts to develop North Korea to prevent the inevitable implosion of its economy while also shielding the North Korean regime from internal collapse. This “grand bargain” is certainly distasteful to the North Korean regime, which is used to getting its own way—thus, Kim Jong Il’s decision to conduct a second nuclear test in May 2009. But when the Americans did not respond and the test instead resulted in even more punitive UN sanctions, the friendless regime was forced to make amends with China. “Despite their public rhetoric about the closeness of their ties,” confided one observer, “officials in both China and North Korea each tell even American officials how much they dislike each other. North Korean officials have on numerous occasions suggested to American officials that it would be in the interest of our two countries to have a strategic relationship to counter China.”14 North Korean officials privately voiced their wariness of Beijing to South Korean diplomats, and worry about China’s “increasing hold on precious minerals and mining rights in the DPRK [and] many oppose mineral concessions as a means to attract Chinese investments.” According to one well-placed source, “Disputes with North Korean counterparts develop all the time … Investment disputes also occur between competing investors in China.” In May 2010, the Saebyŏl Coal Mining Complex in North Hamgyŏng province sealed a contract with a Chinese enterprise. It promised to hand over an “unheard degree of discretion in affairs of personnel management, materials and working methods” to the Chinese. According to one source, the Chinese have been guaranteed “operational independence free from the control of the Saebyŏl party committee, and take 60 percent of net profits.” North Korean workers appear to be happy with the arrangements, as they are now guaranteed steady wages and food. But others are far more pessimistic: “The purse strings in the border regions of our country have basically been handed over to China, and our ‘socialist pride’ is in the hands of China. Any factory where they produce even a small amount of goods has been invested in by the Chinese.”15

North Korea’s increasing dependence on China, however, does not mean that Beijing’s leaders are able to exert complete control over their difficult neighbor. North Korea’s second nuclear test in May 2009 strained relations between the two countries, but Chinese leaders also know from historical experience that such actions are geared more toward North Korea’s domestic audience than the international community. Thus, despite his displeasure with North Korea over the nuclear test, Chinese Premier Wen nevertheless signed an ambitious co-development project with Kim Jong Il the following October.

The project, covering the Chinese cities of Changchun, Jilin, and Tumen, encompasses an area of seventy-three thousand square miles, but it is landlocked by Russia. Kim Jong Il agreed to lease the sea port at Rajin, a gateway to the Pacific, as well as sign on to various economic development projects. In December 2010, for example, China’s Shangdi Guanqun Investment Company signed a letter of intent to invest $2 billion in the Rajin-Sŏnbong economic zone, which represents one of the largest potential investments in North Korea.16 There are already reports that North Korean workers have been dispatched to begin the project, and plans are under way for the building of a new fifty-thousand-kilowatt hydroelectric power plant on the Tumen River.17 North Korea and China have also recently signed an investment pact on building a highway and laying a railroad between Quanhae in Jilin and Rajin-Sŏnbong.

But more telling to the future relations between North Korea and China has been the swift reopening of the border after Kim Jong Il’s passing. When Kim Jong Il’s death was announced on December 19, most people assumed that North Korea would close its frontier with China, at least for the short term. However, within forty-eight hours, “many border crossings sprang open again,” underlying the reality that the new regime can ill afford to cut off its lifeline to China, even for a few days. Although China’s strategy to encourage economic reforms in the North does not appear to be successful, the expansion of trade and investment has nevertheless “unleashed economic forces at least in the border region” as well as created a new group among the country’s elite who have a vested interest in expanding trade.18

Changchun-Jilin-Tumen River (Chang-Ji-Tu) area.

The pressing question that North Korea now confronts in the face of becoming a “fourth province of northeastern China” is how to sell it to the North Korean people. For a regime that has always touted chuch’e as the core principle of its nationalist ideology, such dependence would likely trigger a mass legitimization crisis. It would be hard to justify North Korea’s chuch’e philosophy of self-determination and the regime’s repeated denunciation of South Korean “flunkyism” while becoming an economic satellite of China. Hence, the regime’s continued efforts to demonstrate its “independence” from China and create international crises to galvanize domestic public support for itself. This has become all the more urgent since Kim Jong Il’s death. According to sources familiar with the North Korean situation, Kim Jong Il was “obsessed with creating political stability to allow orderly succession.”19 Chinese leaders, aware of the delicate situation, had tolerated Kim’s antics because they understood he would never actually start a war.

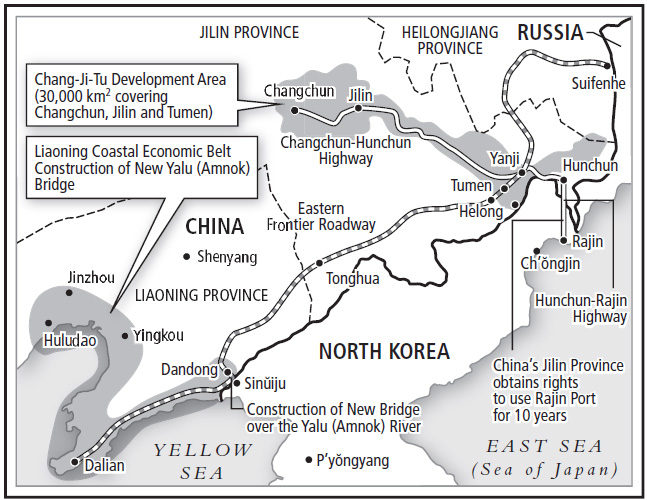

Arirang, North Korea’s mass games in 2010, celebrating Sino–North Korean Friendship and the sixtieth commemoration of the “Victorious Fatherland Liberation War.” (AP/KOREAN CENTRAL NEWS AGENCY)

But instigating crises in response to internal domestic turmoil, a familiar North Korean tactic, has done very little to mask the reality of China’s growing influence over North Korean affairs. This is where the Korean War story plays a vital role in forging a new relationship between the two countries. In years past, the anniversary of the Chinese intervention in the Korean War, which occurred on October 19, 1950, had been worth just a few lines in the North Korean press, if it was mentioned at all.20 In recent years, however, China’s role in North Korea’s Korean War commemorative culture has taken on a strikingly new and prominent role. In August 2010, North Korean officials announced that North Korea’s mass games known as Arirang, the iconic gymnastic and artistic performance scheduled to be performed as part of the commemorative celebrations, would feature two entirely new scenes: “One of them represents the Korean People’s Revolutionary Army and Chinese armed units fighting together against the Japanese imperialists during the anti-Japanese armed struggle. The other portrays the Chinese People’s Volunteers joining the Korean army and people in the Korean War against the imperialist allied forces’ invasion under the banner of resisting America and aiding Korea, safeguarding the home and defending the motherland.” Performers “in Chinese clothes” danced with Chinese props, including “several dozen meter-long dragons, pandas and lions.”21

If the inclusion of Chinese props and dress was not striking enough for a country that has not overtly acknowledged China’s role in the conflict, a grand banquet to commemorate the sixtieth anniversary of the CPV’s entrance into the Korean War was held on October 24, 2010. In his address to members of the visiting delegation of the CPV veterans, the North Korean vice president of the Presidium of the Supreme People’s Assembly, Yang Hyŏng-sŏp, saluted “the CPV’s brave men and our people and army [who fought] side by side, to carry forward the courageous spirit and collective heroism” and made “the Fatherland Liberation War a great victory, by gloriously defending Northeast Asia and world peace.”22 This was followed by an unprecedented official visit to the cemetery of Chinese soldiers killed during the Korean War, including Mao Anying, Mao Zedong’s son.23

On October 26, 2010, Kim Jong Il, center, laid a wreath in front of the grave of Mao Anying, Mao Zedong’s eldest son who died during the Korean War. The CPV Martyrs Cemetery, located in Hoech’ang, South P’yŏngan province, has become an important site for ceremonial visits made by Chinese and North Korean officials. Premier Wen Jiabao visited the cemetery during his October 2009 visit to the DPRK. An official visit to the CPV Cemetery in September 2010 was one of the first major events after Kim Chŏng-ŭn was publicly introduced as his father’s hereditary successor. In October 2012, DPRK state media reported that a memorial ceremony marking the completion of extensive renovation work of the cemetery was held to mark the sixty-second anniversary of the CPV entry into the Korean War. (AP/KOREAN CENTRAL NEWS AGENCY)

Even then, China’s role in the war is construed as being one of “reciprocal obligation” since North Korea had once aided the Chinese in their war against Japan. “The tradition of ties of friendship between the peoples of the DPRK and China, sealed in blood in the joint struggle against U.S. and Japanese imperialisms, the two formidable enemies, has steadily developed on the basis of particularly comradely trust and sense of revolutionary obligation of the leaders of the elder generation of the two countries,” explained the Nodong sinmun, the North Korean party daily, in its October 24, 2010, issue. In short, by equating China’s aid against American “imperialists” in the Korean War with the aid of Korean revolutionaries in fighting Japan in China during World War II, North Korean officials drew attention to the equality of revolutionary comrades in arms based on the bonds of DPRK-China friendship “sealed in blood,” rather than on any indication of super-power “dependence.” The “ties of friendship between the people of the two countries” are thus presented in terms of a familial bond of obligation and respect between younger and older generations:

Kim Il Sung visited China to participate in the function for founding the People’s Republic of China in Juche [chuch’e] 38 [1949] and had his first meeting with Chairman Mao Zedong and Premier Zhou Enlai. Since then, the leaders of the two countries made great efforts to boost the friendly relations between the DPRK and China … In the new century, General Secretary Kim Jong Il paid several visits to China and Chinese party and state leaders including Hu Jintao visited the DPRK, deepening the friendly feelings and comradely fraternity and boosting the DPRK-China friendly and cooperative relations.24

What is remarkable about this passage is not only the parallel that is drawn between Kim Il Sung’s visits to Mao and Kim Jong Il’s visit to Hu Jintao, but also the attempts made to highlight Kim Il Sung’s revolutionary struggle in Manchuria. Since Jilin, Heilongjiang, and Liaoning provinces once comprised the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo, the regime’s current “joint” cooperation with China to develop this area is presented as being foreshadowed by Kim Il Sung’s “hard-fought revolutionary struggle” there. During his visit to Jilin province in August 2010, Kim Jong Il directly linked China’s Northeast development project with his father’s exploits in Manchuria:

Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces are a witness to Korea-China friendship and a historical land dear to the Korean people as Comrade President Kim Il Sung waged a hard-fought revolutionary struggle against the Japanese imperialists together with Chinese comrades in this area, leaving indelible footsteps. He in his lifetime had often recollected this historical land and wanted to visit here again. Carrying his desire with us, we have come here today. Entering the northeastern area of China we have felt that this area, which had been trampled down ruthlessly by the Japanese imperialists, is now vibrant with life, enjoying a splendid development in political, economic, cultural and all other fields under the leadership of the Communist Party of China.25

Percy Toop, a Canadian tourist, photographed this painting on October 27, 2010, at the Rajin Art Gallery. Many experts believe it is a painting of Kim Chŏng-ŭn. What is remarkable is that the setting and layout are similar to those in depictions of the young Kim Il Sung.26 (COURTESY OF PERCY TOOP)

This passage is immediately followed by nostalgic reminiscences of Kim Il Sung’s revolutionary past, which seek, once again, to demonstrate the “unbreakable” bond of friendship between the two countries.

The explicit linkage made between Kim Il Sung’s past exploits in Manchuria and China’s future exploits in Heilongjiang and Jilin provinces also provides clues on how P’yŏngyang decided to approach the delicate transition issue. With Kim Il Sung’s popularity still intact, it makes sense for the regime to bring the Great Leader back to life in the person of his grandson, Kim Chŏng-ŭn. Such a reincarnation myth would be an effective ploy to ensure a smooth succession, since the Great Leader’s untimely death in 1994 has largely absolved him of responsibility for North Korea’s disastrous predicament, the famine and the country’s economic collapse. This “reincarnation” drama was meticulously planned, with North Korean propaganda skillfully playing up the uncanny resemblance between the Great Leader and his grandson. When official photos of Kim Chŏng-ŭn were first released to the public in October 2010, some North Korea watchers even suggested that Kim Chŏng-un may have undergone plastic surgery to look more like his grandfather. Footage released in the week following the announcement of Kim Jong Il’s death showed Kim Chŏng-ŭn visiting a tank division using the same signature mannerisms as his grandfather—walking with his left hand in his pocket and using his right hand to gesture while talking. Kim Chŏng-ŭn also shares the same swept-back hairstyle and protruding belly as the elder Kim; even his gait is reminiscent of the Great Leader’s.27 If Kim Chŏng-ŭn, with Chinese help, can begin a kind of “return to the past,” to the days of Kim Il Sung before the famine, he may prove to be a far more effective leader than his own father. Also telling was the decision to introduce the heir apparent at the sixty-fifth anniversary of the NKWP, on October 10, 2010. On the reviewing stand with Kim Chŏng-ŭn and his father was Zhou Yongkang, China’s point man in North Korea who is helping to oversee the Northeast Asia Project.28

Having embraced Kim Chŏng-ŭn as his father’s legitimate successor, China’s leaders have signaled that they do not support any drastic change in either Sino-DPRK relations or North Korea’s domestic policy, at least in the near future. China will continue to push for economic reforms while exerting pressure on P’yŏngyang’s leaders for more access and faster development of Chinese business interests, particularly in the mineral sector and large projects like at Rajin.

Kim Jong Il, right, and his son Kim Chŏng-ŭn attend a massive parade to mark the sixty-fifth anniversary of the NKWP in P’yŏngyang, October 10, 2010. (AP PHOTOS)

Not surprisingly, South Koreans have become increasingly alarmed by all this talk of Sino–North Korean relations “forged in blood.” They remain deeply suspicious of Chinese influence in North Korea and are wary about China’s “strategic plot to colonize North Korea economically.”29 Relations between the two countries were made even more tense after North Korea’s sinking of the South Korean naval vessel Ch’ŏn’an in March 2010.30 South Korea had initially believed that China, as its largest trading partner, would endorse its position in its quest to seek international justice for the attack. When China wielded its veto power as a UN Security Council member to force a watered-down statement that did not identify North Korean culpability, Seoul responded with anger. Relations between the two countries are currently at their lowest since they established diplomatic ties in 1992.31 In retaliation for North Korean provocations, the Yi administration cut off all aid to North Korea, including food aid. However, by adopting a hard-line stance toward the Kim Jong Il regime, South Korea essentially surrendered its economic leverage over North Korea to China. Some South Korean lawmakers expressed concern: “I’m worried that North Korea is getting too close and familiar to China in a bid to push third-generation succession,” said Representative An Sang-su, chairman of the ruling Grand National Party. “Would we be able to stop North Korea, if it decides to be under the control of China?”32

But the reality is that few South Koreans today are ready to take on the burdens of unification. In the 1990s, more than 80 percent of South Koreans believed that unification was essential; in 2011, that number dropped to 56 percent. Roughly 41 percent of those in their twenties believe unification is imperative, and among teenagers, that figure drops closer to 20 percent.33 This huge drop in support is in large part due to the failed promises of Kim Dae-jung’s Sunshine Policy. In November 2010, the South Korean Unification Ministry released a white paper which declared that the policy was dead. “Despite outward development over the past decade,” the white paper said, “inter-Korean relations have been under criticism from the public in terms of quality and process. They have in fact, become increasingly disillusioned with the North and more worried about security as the North continued its nuclear arms program.” Furthermore, despite the massive aid from South Korea and inter-Korea exchanges and cooperation over the last decades, no “satisfactory progress has been made in the issue of separated families, South Korean prisoners of war and abduction victims.” The paper concluded, “The North has made no positive change in proportion to the aid and cooperation from South Korea.”34

Few South Koreans harbor illusions about the dire state of the North Korean economy or the tremendous costs of unification. South Koreans also worry about the toll unification will take on the fabric of their society. The Korean Employers Federation predicted that if North Korea collapsed, up to 3.5 million people could flood South Korea. “Even under a conservative estimate, up to 1.6 million North Koreans may move to South Korea, mainly because of the huge difference in wages and employment opportunity,” the Federation said. “Such a wholesale movement of people could seriously disrupt the local labor market and cause other social problems.”35 While many older South Koreans give lip service to the ideal of a reunified peninsula, they qualify their support by talking about it taking place over the long term, and preferably after they are dead.36

Thus it appears that it will be up to China to drag North Korea into the twenty-first century and finally end the Korean War.37 North Korean leaders understand this, which is why they have already begun to accommodate China into their national narrative and China’s presence into Kim Il Sung’s revolutionary past. Hence all the hoopla recently about the Korean War, Kim’s Manchurian exploits, and the two countries’ bilateral friendship “forged in blood.” This does not mean, however, that the new Kim Chŏng-ŭn regime will cease making trouble for China. Since the stability and legitimacy of the regime still rest firmly on the myth of Kim Il Sung, his anti-imperialist exploits, and the principle of chuch’e, China knows that it must allow the regime to assert some independence if it is to avoid collapse. Just how much “independence” China will tolerate from its recalcitrant neighbor remains to be seen. Needing both to preserve his rule and to build a “strong and prosperous nation,” Kim Chŏng-ŭn is now faced with resolving the perplexing contradictions of instituting vital economic reforms under Chinese guidance while at the same time preserving the chuch’e principle so crucial to the legitimacy of the regime during a delicate transition period.

Over one hundred years has passed since China was forced to leave the Korean peninsula after its humiliating defeat in the 1894–95 Sino-Japanese War. That war marked China’s decline and Japan’s ascendancy in East Asian affairs. In the long aftermath of the war fifty years later, in which China saved North Korea from certain defeat, a revitalized China has returned to the Korean peninsula to reclaim its once-dominant position in Asia. China’s rise has many implications for the region, but one of them certainly is the role it will play in ending the war on the Korean peninsula.

The events connected to the ending of the Korean War will be momentous, and the uncertainties surrounding North Korea’s potential economic collapse and China’s absorption of North Korea’s economy are disquieting, as much for the millions of hungry North Koreans as for the prosperous Koreans in the South. How will South Korea react to China’s intrusion into North Korea? As for the United States, whose military might and economic power came of age both during and after the Korean War, the specter of a rising China is certainly unnerving, but more worrying, perhaps, than China’s role in ending the war in Korea is what this might signal for China’s new place on the world stage. Understanding and responding to these changes will require reflection on the lessons and legacies of the unending Korean War and the role this conflict has played, and will continue to play, in shaping the region’s past and future.

As this book was going to print, it was announced that Pak Kŭn-hye, Park Chung Hee’s daughter, was elected president of South Korea on December 19, 2012. As the eldest daughter of Park Chung Hee and Yuk Yŏng-su, Pak Kŭn-hye took on the role of first lady after her mother was tragically killed in a botched assassination attempt on her father’s life in 1974. Not only is Pak the first female leader in Korea’s millennium-long history (if we do not count the few Silla queens who ruled between the third and seventh century CE), her election also signals another “return of the past” as she must now deal with Kim Chŏng-ŭn, Kim Il Sung’s grandson, in the ongoing struggle between North and South Korea. How this legitimacy struggle plays out between the progenies of these two momentous leaders of Korea’s history adds a new and ironic twist to the unending war in Korea and China’s role in resolving this long-standing family feud.