1

… we are as a City set upon an hill.

Reverend Peter Bulkeley

Concord, 1646

This is a story about too many funerals in a single church, and a congregation of good men and women.

Well, it would be going too far to pretend that everyone in the parish was a model of rectitude. Most were the usual confusing mixture of virtues and faults. It would be more truthful to say that the story concerns only three good men: the Reverend Joseph Bold, parishioner Homer Kelly, and that stalwart pillar of the church, Edward Bell.

No, once again the list is too long. Homer Kelly’s name should be withdrawn right away, since Homer was certainly afflicted with many grievous flaws.

And to say baldly that Joseph Bold, the new minister in the Old West Church of Nashoba, Massachusetts, was a good man would be giving him too much credit. It’s true that Joe had once been an example of peerless benevolence, but lately he seemed to have lost the knack.

So that leaves only the presiding officer of the Parish Committee, Ed Bell. Surely no one would question Ed’s goodness. As you would describe a spiral staircase by twisting your hand in the air, so you would define human virtue by pointing at Ed. It came to him so naturally he didn’t even have to think about it. What’s more, it drew people to him rather than driving them away as some kinds of pious behavior are apt to do.

As for the funerals, they began slowly, then came in a rush, one after the other. They didn’t seem strange at first—except for the murder, of course. A murder isn’t exactly normal in a little suburban town like Nashoba. But neither was the frequency of the other deaths something you would expect in a place like that. As the funerals went on and on, people began to be upset and bewildered.

In the matter of the actual murder, Homer Kelly was useful, drawing on the experience of his old days in the office of the district attorney of Middlesex County. But he wasn’t very helpful in explaining the rest. He simply couldn’t understand why the angel of death was suddenly so interested in Old West Church. What about the other two parishes in the town of Nashoba? “Look at the Catholics of St. Barbara’s,” he complained to his wife. “All in rude good health, so far as I know. And the Lutherans are skipping right along to the Church of the Good Shepherd, right? Rollicking in marriages and baptisms? Are the Methodists sick? Or the Jews? The Baptists? The Quakers? The Christian Scientists? No, indeed, they’re all in the pink. Even the atheists are thriving. It’s only the Unitarians and Congregationalists of Old West Church who are keeling over. What does it mean?”

Unfortunately the new minister, Joseph Bold, seemed forlornly unable to reassure the people of his congregation. And certainly the chief of the Nashoba police, Peter Terry, was as much in the dark as anybody else.

So once again there was only the steadfast support of Ed Bell, with his comforting reminders that most of the deceased parishioners had been ill anyway, that coincidences do happen, even in dying, and that his fellow church members should set their faces forward, because life had to go on, after all.

Good old Ed. What a treasure he was to the whole parish, and of course to his friends and family. It’s true that his prodigies of kindness sometimes irritated his wife, Lorraine, but how could you complain about a husband who was a community institution, whose disposition was sunny, whose judgment was sensible, whose actions were compassionate and without guile?

“It’s just that he’s so stubborn,” said Lorraine, confiding in her friend Geneva Jones.

“Can’t you argue with him?” said Geneva.

“Argue! What good would that do? He’s got this inner compass, that’s the trouble. It’s as if he could see the needle pointing north. Of course sometimes he’s wrong, dead wrong, but do you think he ever feels guilty afterward? Guilty? Never! The man was born without any sense of guilt. Isn’t that amazing?”

“Incredible,” agreed Geneva solemnly.

Sometimes Lorraine wondered how Ed had become the kind of man he was. It surely hadn’t been his parents’ doing. Oh, they had been all right, in their way, but they certainly didn’t account for a phenomenon like Ed. “He was just born like that,” Ed’s mother had told Lorraine, tossing her hands helplessly. “I used to wish he would do something naughty, but he hardly ever did. His sister, now—good gracious, did I ever tell you about the time Doris was expelled from school?”

So it was one of those random mysterious things, perhaps even an interference by God in human affairs. Who could tell? Taking everything together, Lorraine knew she was lucky to be married to a man like Ed. Therefore she put up with his amiable charities as cheerfully as she could, although their consequences were often extremely awkward.

There was the madman who had arrived on the doorstep with all his possessions, to be invited in by Ed and installed in the guest room. He had stayed for a month, shouting without cease, departing at last for a mental hospital, leaving behind him a plague of cockroaches.

There was the dear old widow to whom Ed had lent money and given comfort, who had stood up one day in church to accuse him of robbery and rape.

And there was the good cause for which Ed had exhausted himself raising money, until the treasurer pilfered the funds and took off for parts unknown.

“Honestly, Ed,” Lorraine had said, “you should have known better. I could tell right away the man couldn’t be trusted.” But even Lorraine had to admit there were plenty of other times when Ed had knocked himself out for somebody and yet nothing actually bad had happened, as far as she could determine.

As for the selection of the new minister, it was too soon to tell. Lorraine didn’t know whether Ed had been right or wrong in persuading the rest of the selection committee to choose Joseph Bold, even when everybody on the committee knew the man’s wife was in awful trouble.

“We’ll see them through it,” Ed had told them. “Why not? What’s a church for anyway?” And this question had knocked the rest of the committee members back on their heels. They had looked at each other, dazed, and voted to accept the candidacy of Joseph Bold.

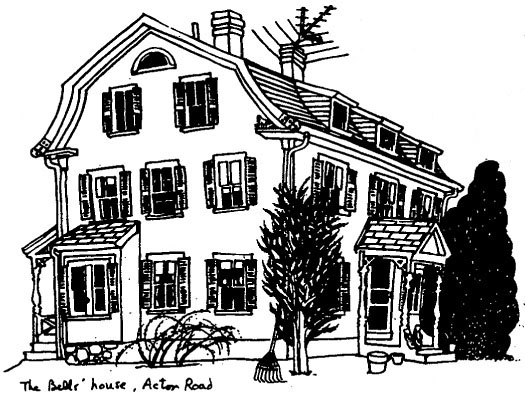

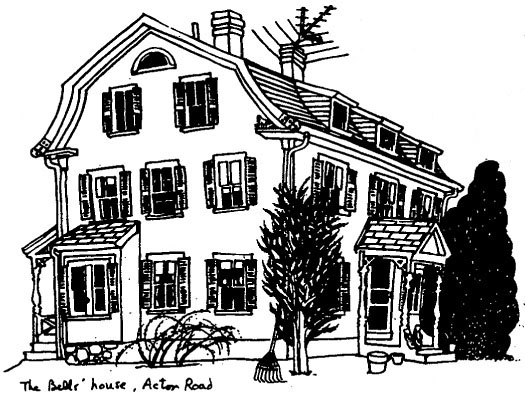

On the dawn of the Sunday morning in March when the new minister was to appear for the first time to his congregation, Lorraine still hadn’t made up her mind about him, although she and Ed had helped the Bolds move into the parsonage and had brought home three loads of their laundry because the parsonage washing machine wasn’t hooked up yet. Oh, they were nice people, all right, but they seemed terribly young, and they were certainly headed for grief.

It was typical of Ed that he had more to do that morning than there was time for. He had been up most of the night writing a welcome to the new minister to be read by the members of the selection committee, and now he had to deliver his typed copies all over town.

“I’ll be back soon,” he said. “We’ve got to get there early. Is Eleanor up yet?”

“I haven’t heard a peep,” said Lorraine, pulling bobby pins out of her curlers, unwinding her hair.

“Well, no wonder. Poor kid, she must be worn out. Did you know she was reading half the night? When I went up to bed, it was four in the morning, and I saw a light under her door, so I poked my head in and told her to go to sleep, and you know what she said?” Ed laughed. “‘Oh, that awful Lydia,’ she said. ‘Poor Elizabeth, she has to go home because of Lydia, just when Mr. Darcy is being so incredibly nice.’ So I shut the door and let her alone.”

“I wish I were fourteen again,” said Lorraine, tumbling the curlers into a drawer. “Imagine reading Jane Austen for the first time.”

But in Eleanor’s bedroom down the hall, Pride and Prejudice lay neglected under a copy of Seventeen. Eleanor was sitting on the edge of her bed, studying the cover of the magazine with intense interest, noticing the luscious pinkness of the cover girl’s lipstick, the dark mascara of her eyelashes, and the headlines under her chin: SUMMER ROMANCE, CAN THE MAGIC LAST? SHOULD YOU KISS AND TELL?

Eleanor’s mother was knocking on the door. “Eleanor, dear, get up.”

“I am up,” said Eleanor loudly. Then, tossing the magazine aside, she went to the mirror and got to work on her face, devoting herself to the task with total absorption. Choosing a lipstick called Kissing Pink, she outlined her mouth, then worked over her cheeks with Naturally Glamorous Blush-on in Enchanted Orchid and did subtle things to her eyes with Soft Plum eyeliner and Flame Glo Brown Velvet mascara.

The makeup was for the benefit of Bo Harris. Would Bo be in church this morning? Bo didn’t often come to church, but today was sort of different because of the new minister. If Bo didn’t turn up, then all this work was a big waste of Eleanor’s time.

Eleanor Bell was fourteen, the last of the five Bell children still at home, the apple of her father’s eye. It wasn’t that Ed had not been a good father to Stanton and Margie and Lewis and Barbara. It was just that he had more time to be with Eleanor. After forty-two years of practicing law for an international corporation manufacturing valves, boilers, and radiators, he was at last retired, although he still went to a lot of meetings because he was on the boards of a bunch of other companies.

“Now, Ed, don’t get trapped on the way,” said Lorraine. “The last time you went out on an errand, you helped somebody bury a dog and you were gone for hours.”

“Oh, I promise,” vowed Ed. “I’ll just slap these copies around to my committee members and hurry right back.”