40

… by sin, we an fallen from Cod and our happiness; have incurred his holy displeasure, and deserve his wrath.

Reverend Daniel Bliss

Concord, 1755

Peter Terry had to admit himself defeated. He had never felt more wretched in his life.

“All right,” he said, “all right. We’ll have the stuff analyzed. Can you wait until then to destroy the finest guy in town? My God, Flo, I don’t understand you. I just don’t see what’s got into you.”

Flo threw up her hands, calling upon heaven to witness this folly on the part of her husband. “Even now? Even now you don’t understand? You who are responsible for the health and safety of all the citizens of Nashoba, Massachusetts? You don’t understand why we have to stop someone who is killing his fellow men and women? Who is ready to do it again? Why didn’t he throw those things away? He’s keeping them handy, that’s why. He’s ready to use those needles again.”

“But the man is a saint,” grumbled Pete. “You want to make him a martyr? That’s what he’ll be, a martyred saint.”

“A saint?” cried Flo. “A saint? Some crazy kind of saint, to be taking God’s power into his own hands. You call that being a saint?”

Then Pete accused the wife of his bosom of being no better than Pontius Pilate, or those people who had burned Joan of Arc at the stake. Flo’s feelings were terribly hurt.

Next day the promise of Saturday’s basking warmth was repeated in the mild dawn of Sunday morning. Homer and Mary Kelly paid an early pre-church visit to Ed Bell. Homer sat down with Ed in his living room and told him gloomily what Flo Terry had discovered in his basement.

Ed seemed more amused than anything. “Oh, she found them, did she?”

“I’m afraid so.”

“Clever girl. I must say, I thought her husband let me off far too easily.”

“But, Ed, do you know what this means?”

“Oh, I can imagine.” Ed smiled at Homer genially. “And maybe in the long run it will make a point. At least maybe some people will begin to think about it.”

Homer looked at him solemnly. “Isn’t the loss of your freedom a high price to pay for making a point?”

“I don’t know, Homer.” Ed looked at Homer candidly. “I’ll find out, won’t I?”

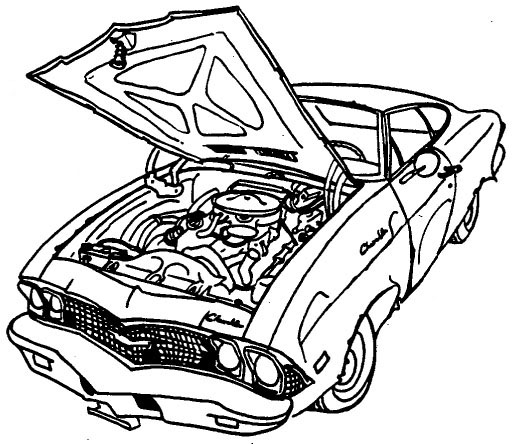

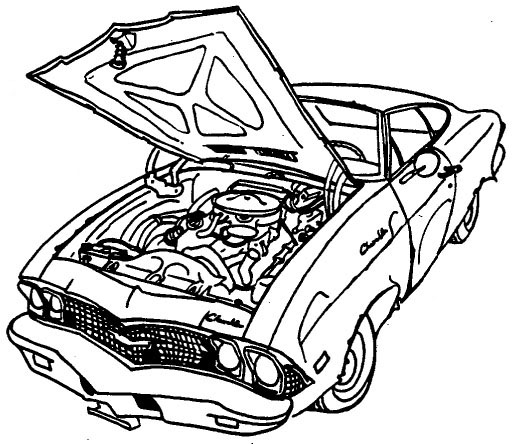

Out-of-doors Mary Kelly and Lorraine Bell stood in the bald sunlight of mid-March, watching Bo Harris work on his car. The Chevy had been rolled out of the garage, where it had spent the winter while Ed’s car sat outside in the snow and cold. Bo had been unable to work on it through December, January, and February, but now he was coming down the homestretch. His repairs were almost done.

Lorraine stared at Bo’s feet, which, as usual, were sticking out from under the Chevy, twitching and jerking as he struggled with something under the chassis. Then she looked suspiciously at Mary. “What are you people here for? What does Homer want with Ed?”

Mary hesitated, unable to tell a comforting lie. Looking up at the back porch, she said, “May we sit in the kitchen? I’ll tell you what he told me.”

As they walked up the steps, Paul Dobbs came out on the porch. He was running a comb through his hair. He said good morning cheerfully to Mary and Lorraine, then bounded briskly down the steps and stooped to look under the car at Bo. “Hey,” said Paul, “when you going to finish this pile of junk?”

“Pretty soon,” said Bo, crawling out from under. “I’m just bleeding the hydraulic system.”

“Gimme a break,” said Paul. “You been bleeding the whole goddamn car for a year. That heap’s never going to get on the road. Who you kidding?”

“Next weekend,” promised Bo, springing to his feet. “Just a couple more little bitty details, that’s all.”

Eleanor came out on the porch and leaned on the railing, dressed for church in an outfit of pink bandannas. She had run it up quickly on the sewing machine yesterday after finishing at the copy center. Then last night she had braided her hair in dozens of pigtails, and this morning she had undone all the pigtails, and brushed them out so that now her hair was a bright tangled thicket, pouring over her bare arms. Her lips looked wet because of the varnish in her lipstick.

Paul whistled, appreciating the result of all her hard work. Bo Harris didn’t even look up.

Eleanor was in a queer mood. Stumping across the driveway, she stood in front of Bo, forcing him to look at her. But instead of a pink-and-gold vision staring him in the face, Bo saw only what was in his mind’s eye, the gritty underside of the Chevy and a hoped-for bead of brake fluid on the hydraulic nipple. The bead of fluid would mean the air had at last been exhausted from the system. So far there had been no little drop of fluid. He would have to try again. And there was a crack in the hydraulic hose. He needed a new hose. Was the Icehouse Garage open on Sunday?

Eleanor had knocked herself out for nothing. “Take me for a ride,” she said.

“Oh, no,” said Bo. “Not yet. This car’s not ready to go yet.”

“But it’s been so long.”

“It’s just the brakes. That’s all. And the muffler. And the hand-brake cable’s shot. And then I’ve got to get the car insured. I’ve got to go to Watertown, get a license at the registry. And the whole thing has to be inspected. I’ve got to get a sticker.”

Eleanor was angry. She felt goaded out of herself. This morning she was someone else entirely, carried beyond herself by her grievance, by the thought of the summer and fall and winter she had spent making herself beautiful for Bo. All those cold Sunday afternoons in the freezing garage trying to help, all those Saturdays in the copy center earning money for makeup and clothes to dazzle Bo Harris, who cared for nothing but his stupid car, who never saw her at all, who treated her like a stick or a stone! To Bo, she was only a pair of hands to shine a flashlight on something, or extra arms for carrying the other end of the transmission, or an extra foot to hold down the accelerator while he checked a connection under the hood. He never saw the person to whom the hands and arms and feet belonged. He never saw the girl whose name was Eleanor Bell. He never saw what Eleanor saw in the mirror every day, a pretty girl, a pretty, pretty girl—everybody said so! She was really, really pretty! And Bo didn’t see it. He didn’t see her at all.

“Listen,” said Eleanor, her voice tight in her throat. “You could drive around the school parking lot. Why not? Nobody would see you on the road. It’s only a mile away. Why not? Why not? Take me for a ride.”

But Bo was back under the car, taking a last loving look at the brake shoe on the left side. Hauling himself out again, he stood and picked up his bicycle. “I’ve got to find a hose. I’ll be back sooner or later.” Putting one foot on the pedal, he coasted gracefully down the driveway standing up, then put the other leg over and floated onto Acton Road, poised on the light frame of his bike. Once again Eleanor stared at his disappearing back, her face burning. She wanted to scream.

“Big jerk,” said Paul, looking sympathetically at Eleanor. “Listen, you want a ride? I’ll give you a ride.”

Eleanor looked at Paul. “But he said—he said something isn’t finished yet.”

“Oh, sure, he said. He doesn’t want to give you a ride. First time out in that car, he’ll take some other girl. What do you want to bet? After you been helping him all this time, he’s not going to give you no ride.”

Eleanor stared at the fresh tufts of grass springing up in the driveway. It wasn’t fair. It wasn’t fair.

She looked up to see the big Ford pickup that belonged to Mr. and Mrs. Kelly turning out of the driveway onto Acton Road. Her father was running down the porch steps, calling to her, “Ready for church, Ellie? Where’s your mother?”

Eleanor walked stiffly around the house to the front door, and found her mother scrabbling in her pocketbook in the hall. She looked anxious and absentminded, as if her mind were on something else entirely. “Here, dear,” she said. “Here’s something for the collection plate.”

“Listen, Mom, I’m not going to church today. I feel sort of awful. I mean, I think I’ll stay home.”

“Why, Eleanor.” Lorraine Bell suddenly focused her attention entirely on her daughter. She reached out a hand to feel her forehead. “Well, I don’t know.”

“Hey, you girls, are you coming?” shouted Ed. The car door slammed.

“Well, all right, dear,” said Lorraine. “Just as you wish. You want to lie down on the sofa?”

“Maybe I will,” said Eleanor. “I guess so. Maybe I’ll just go lie down.”