44

The heart … is not a superficial sensibility,—the shallow pool that changes with every change of temperature. The well is deep.…

Reverend Barzillai Frost

Concord, 1856

Joe Bold plucked his robe off its hook and darted a glance out the window. The cloudburst that had been going on all morning was over. The cold gray sky was punctured by cavities of blue. Crossing the back entry, where umbrellas lolled on the floor and coats hung dripping from the rack, he opened the door of the sanctuary and mounted the steps of the pulpit to face once more his gathered parish.

Homer and Mary Kelly were present, as usual, although Homer didn’t know how much longer he would be a loyal member of the congregation. He was finished at last with his history of the spread of the faith from the town of Concord. If God wanted to put the roof back on the church, it was all right with Homer. Let Him reach out with his stupendous hand and turn off the stopcocks of all those gushing faucets. But of course the final result of Homer’s researches was disappointing. His history wasn’t at all what he had intended. Oh, the Reverend William Lawrence of Lincoln was in there with all his recorded possessions—his six chairs, his eight-day clock—and so was Ezra Ripley, who had preached in the Concord church for sixty years, and so were all those other august ministerial presences, looming out of the histories of all these little towns.

But where were Rosemary Hill and Betsy Bucky? Where was Ed Bell? Where was Bo Harris? Where were the Farrars and Wheelers and Bloods and all the rest of the nameless congregations of yesterday? Well, of course a lot of sermons had survived, and Homer had taken dutiful note of them. How those old ministers had talked and ranted from their several pulpits! The congregations must have listened at least some of the time, and taken it all in, while out-of-doors the thick rushing life of their parishes went on just as it did right now, and the sow farrowed, and the horse died, and the barn burned down, and the price of apples rose and fell, and the baby cried, and the wife grew troubled in her mind, and the orchard blossomed, and the rugged trunks of the sugar maples were flooded with sap, and in Icehouse Pond the fish darted and the Canada geese came down to feed. It was this urgent life that had spoken in one voice from Parson Bulkeley in Concord in 1635, and in another from Reverend Stearns in Lincoln in 1795, in still another from Reverend Stacy in Carlisle in 1835, and in yet another from Reverend Joseph Bold in Nashoba right here and now. It would never stop talking, it would forever keep up its ceaseless murmur, its hoarse musical shout. Translated in the pulpit, the words would come out different, odd perhaps, peculiar often, sometimes dead wrong. And yet all of these reverend clergy would go right on cocking their ears and whispering, “Listen, did somebody say something? I could have sworn I heard something. Listen to that! Right now! Hear that?”

For Homer, then, the taps were turning off. But for Joseph Bold they were turning on. Looking over the pews this morning, he no longer beheld his parishioners as creatures of field and jungle. His vision had been increasing in severe acuity for months, and now he saw them magnified, as if he were gazing through an enormous hand lens. Clearly visible were individual pores and freckles, wens and pockmarks. It was painfully apparent that they were a spotted flock. Then, as they stood up to sing the first hymn, their troubles rose up too, and smote him, and Joe rocked back on his heels. Good God, there in the front row was Parker Upshaw, his dignity mortified by the loss of his job, and behind him sat Lorraine Bell, still embittered and unreconciled to the accident that had killed her husband. And smack in the middle of the rows of pews was that extraordinary moral enigma, Betsy Bucky. And Arthur Spinney had been cracking up lately, and Deborah Shooky looked wretched, and Maud Starr with her hungry face was a perpetual nuisance, and how could a person be of use to Jerry Gibby as he clawed his way up the polished glass hill of middle-class prosperity? Then Joe blinked as a light flared up in one of the box pews. Good heavens, what was that? Oh, it was only Joan Sawyer, sitting directly in the path of the sun as it burst out from behind the clouds and hurled a burning ray through the window.

The words of the hymn were by John Bunyan:

He who would valiant be

’Gainst all disaster,

Let him in constancy

Follow the Master.…

Joan Sawyer was blinded. She couldn’t see the words on the page because the sunlight had kindled her lashes like sparks. Looking past the glare from her hymnbook, she could dimly perceive the dark robe of the minister on the pulpit. His head was lowered. His lips were barely moving:

No foes shall stay his might,

Though he with giants fight;

He will make good his right

To be a pilgrim.

The plate was passed, the dollar bills dropped in, and behind the reading desk Joe fell back on the velvet chair, assailed by another frightful thought. What about Paul Dobbs, the boy who had been driving the car that killed Ed Bell? It occurred to Joe that he was going to have to do something about young Paul. And once he started, he would have to go right on doing it. And Paul was only the beginning. Joe’s head reeled with the monstrous statistics of human poverty, inadequacy, wretchedness, and self-destruction. It was as though the glittering surface illusion by which he had so long been mesmerized had parted like a veil to reveal the tortured condition of his fellow men and women. The bright illusion was still there—the watery images of the windows creeping across the wall, Joan Sawyer glowing like a torch—but these elegancies were of no particular use to anybody, except perhaps as a voiceless congratulation of some kind. Bully for you, said the rainbow as you helped an old lady across the street. Not bad, if I do say so myself, twittered the singing bird. The impassive majesty of nature was what you got for dogged acts of kindness. Well, the truth was, you got the majesty anyway, kindness or no kindness. But looked at as a bargain, it made some kind of balance in the world, tit for tat.

Standing up again, Joe turned over his sermon notes, transfixed by this discovery, while outside the window the leaves clinging to the oak tree fluttered in felicitation, Many happy returns of the day, and the sun clapped its hands in sarcastic tribute, as if to say, What a jerk! You finally figured it out. You certainly took your time.

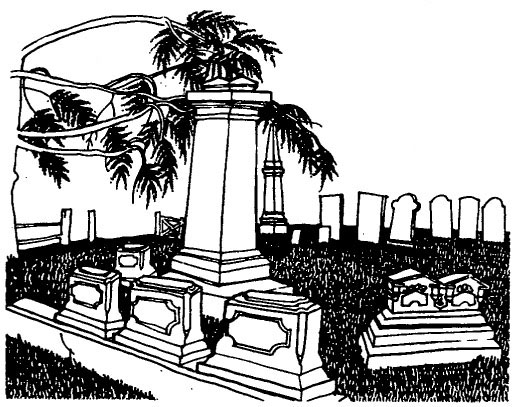

After supper on that chill November day, as the lid of clouds drew off over the ocean, leaving the bony landscape of southern New England without protection from the cold, Homer and Mary Kelly bundled up and drove back to Nashoba to visit the place where Ed Bell was buried.

They found it in the new part of the Old West cemetery at the top of the hill, not far from Arlene Pott’s gravestone, and Carl Bucky’s and Agatha Palmer’s. As they stood silently looking at it, Homer was distracted by something over his shoulder. Glancing back, he saw the full moon coming up beyond the thicket of trees to the east, flattened into an oblate spheroid. The other way, above the crest of the hill, the sky glowed with the remaining shreds of the sunset. It was like that moment on the river when Joe Bold had plucked out of the advancing evening the instant when sunlight and moonlight were equal. It was that time again.

Through the thick twilight, Homer walked out of the cemetery with Mary, remembering Ed’s comic dance with straw hat and stick. As the moon rose and the sun declined, the memory struck the same celestial balance. It was a joke in sidereal time, and the laughter echoed from west to east, from sunset to moon-rise.

The man’s death was a calamity. But he had lived a good life. He had set an example. Surely there was no question about it, that Ed Bell had been a lasting monument of generosity and righteousness?